Lost amidst a huge coniferous forest is a small insignificant hill that is now called ‘Ephraim’s Pinch’. Many people see this name marked on the Ordnance Survey map and wonder what it refers to. It actually relates to a sad story about a local man called ‘Ephraim’. He was a young man who lived in the Widecombe area who had fallen in love with a pretty farmer’s daughter. Often on a warm summers evening they would meet at a small granite bridge called Grendon Bridge. Here as the sun slowly sank behind the huge ridge of Hameldon they would plan their future. As in everyman’s life the time came to approach the girls father for permission to marry his daughter. So one Sunday afternoon, dressed in his best suit and boots he trudged up to the farmhouse. After checking his appearance in the reflection of the duck pond he nervously knocked on the rough wooden kitchen door. The farm dogs, who as it was Sunday were chained to their kennels, snapped and snarled at him, luckily the length of the chains just stopped short of the doorstep. It seemed an age before the farmer finally came to see who was ‘a calling’ and when he flung the door open it was clear he had just be woken up from his Sunday sleep. To say he was not in the best of moods was an understatement. “Well young Ephraim, what be ee after, a bangin that door zo ‘ard” on the Sabbath?”. The young man stammered and stuttered and finally got around to saying that he was “there on mighty important doings”. At which point he was finally let into the kitchen. “Better way get on with it” the farmer growled. Ephraim decided that if you don’t ask you don’t get and came straight out with why he was there. The farmer scowled at him in silence, the only sound being the tick, tick of the old mantle clock and occasional crack and spit from the old apple log that was smoldering in the hearth. The farmer sniffed, puffed and sat down in the old carver chair. Taking out his old clay pipe he reached up to the mantle and took down an old ‘baccy’ pot and with great deliberation filled the yellow stained bowl, he sighed again as he took an reed spill which he pushed into the glowing apple logs. A smoky flame appeared at the end of the spill which with the help of some mighty sucks on the stem of the pipe soon had the baccy ‘a going’. Ephraim felt as if his legs were going to fold, amidst huge clouds of tobacco smoke the farmer sniffed again and jabbing the stem end of his pipe in the young mans direction announced his decision. “This farm ‘as broken my fathers back and its a brakin’ mine, any man who wants to wed my daughter must prove his salt. So young Ephraim if you wants to be that man you must fetch up 20 stooks of wheat vrom Widdicum to Runnage where us will mill it for ee, then ee must tote’ the sack directly down to Widdicum without stopping. If ee can do this then ee ‘ave proved yer worth and ee can surely marry my maid”. Ephraim was delighted, a wide grin spread across his face, why 20 stooks of wheat and a sack of flour would be nothing for his little moor pony to carry. “Thank ee farmer, I an’ me pawny will bring the stooks up on the morrow” Ephraim exclaimed. The old farmer took another long draw on his pipe, his eyes narrowed as he looked straight into Ephraim’s soul, a shiver ran down his back, “did I say ee culd use a pawny, no boy ee must a carry it on yer own”. Ephraim was dumb struck, 20 stooks up and a sack of flour back, that meant carrying them 8 miles up and over the steep ridge of Hameldon and then down the other side and up one long hill to Runnage and the back again to Widecombe. He knew if all the plans they had made for a happy future were to be, he would have to accept the challenge. “Tis a wicked ‘ard thing you ask but Farmer I tell ee twill be done on the morrow, and I thank ee for yer time on this Sabbath”. Having said that, with head hung low he turned and walked out of the kitchen.

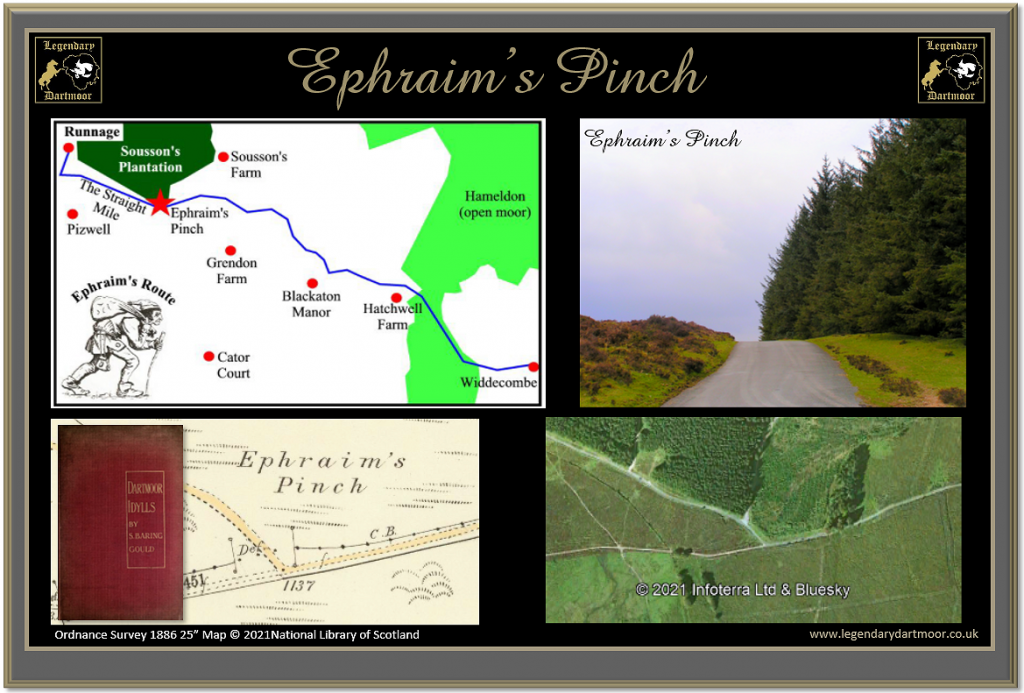

Luckily the next day dawned crisp and clear, he was dreading the thought of a moor mist coming down. With great determination he gathered his 20 stooks, tied them in a tight bundle, heaved them on his back and set off up Church Lane towards the mighty hogback of Hameldon ridge. By the time he reached the top he was drained, the sweat was pouring from his brow and trickling down in stinging streams into his eyes. His lungs were aching and his legs were like leaden drainpipes. All he wanted to do was rest but the sight of the old farmer stood on top of Langworthy hill spurred him on. He was allowed some respite as the journey was now downhill all the way to Hatchwell Corner and then on to Gamble Cott. On and on he slogged, wheat straw and grains had fallen into his shirt and were chaffing his shoulders, it was as if a pumice stone was rubbing his flesh. After Gamble Cott he crossed the small bridge that went over the little Broadaford Brook, he then had another steep climb up past Blackaton Manor and on to the old quarry, past the Love Lane enclosures and ever upwards to the small Grendon Bridge where him and his sweetheart met. As he crossed the bridge the sound of the gurgling brook reminded him of how thirsty he was, his lips had dried and his tongue stuck obstinately to the roof of his mouth. His nose was full of wheat dust which made breathing ever more difficult. Ephraim toiled onwards, past Scutley Bogs and on to Grendon. By the time he reached Grendon Bottom Gate the only thing that was keeping him going was the knowledge that once he crested the small hill ahead he would be on the ‘Straight Mile’ which was a level even track. How he hated that farmer who had now positioned himself by the ancient ‘Ringastan’ stone circle, watching every painful step just waiting for him to falter. As Ephraim started the ascent of the hill a stabbing stitch pain made him bend double, cramp was ripping at his calf muscles and his lungs just could not drag in enough air. His head began to swim and a dull ache had started in his left arm. He was no longer sweating simply because there was no moisture left in his body to sweat. The pain in his arm got worse and just as the crest of the hill came into sight a mighty stabbing pain lurched through his chest. Slowly Ephraim sank to his knees, the weight of the bundled straw dragged him backward and as he looked up into the blue sky he saw a buzzard slowly drifting upwards into the heavens. His eyes closed wearily and it was all he could do to drag them open again. When he did they fluttered like a sparrows wings and he could see ‘old Mordichai’ the buzzard circling above him. The sweet smell of the harvest wheat seemed to engulf him and he eyes shut for the final time, somehow he managed to find enough breath to give a faint gasp and then he too slowly drifted up into the moorland therms to join the buzzard. From that day onwards the small hill was known as ‘Ephraim’s Pinch’ in memory of a young moorman who died for the sake of his true love. Below is a map showing the fateful journey of Ephraim.

It was the Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould who recorded this tale. A version of his story appeared in the Lyttelton Times in the May of 1895. Interestingly at the end of the story he wrote; “But I observe that on the new ordnance of 1893 “Ephraim’s Pinch” is omitted. Can it be that the surveyors did not think the name worth preserving? Can it be that Ephraim and his “pinch” are forgotten on the moor? Alas – time with her waves washed out the writings on the sands. May my humble pen serve to preserve the memory of Ephraim and his Pinch.” A year later in his book ‘Dartmoor Idylls’ which was published in 1896 where he retold the tale. Clearly from his comments the legend of Ephraim dated way back in time and he simply revived it in his own words.

Another version of this tale relates that Ephraim laid a bet that he could not carry a sack of corn from Widecombe to Postbridge without dropping it. When he got to the small hill by Grendon he could go no further and dropped the sack exclaiming that he “found the pinch too much for him”. Ever since that day the hill was known as Ephraim’s Pinch.

The interesting fact of the first tale is the the route Ephraim had to take is the old church path that ran from the Pizwell and Runnage tenements to Widecombe church. This old track was regularly used by the inhabitants of the ancient tenement farms to get to church. Everything would come this way, churchgoers, coffins and funeral processions because Widecombe church was the nearest church. The first mention of the church way is in the Bailiff’s account of the Forest manor in 1491. Prior to 1260 the holders of the tenements had to use Lydford church and would have to walk the ‘Lych Way‘ which was a trans moor route of some 12 miles. It was in 1260 that Bishop Bronescombe gave leave for the tenement holders to use Widecombe church instead. Hemery 1983 p.29-30. Thus far I have been unable to find any mention of a grist mill being at Runnage. Hemery mentions that there was one at Widecombe p.674 Woods, 1996, p.97 is more informative and notes that in medieval times there were possibly two mills at Widecombe and others within a mile radius at Cockington, Jordan and Ponsworthy. There was also a mill at Babeny. Of this Crossing 1990 p.459, mentions a 1344 account of the Prince’s manors stating that in 1302 or 1303 the holders of this tenement built a mill… The hill behind Babeny is known as Mill Hill giving further credence to the matter.

With regard to the actual place name, Ephraim is suggestive of a personal name but Pinch is more elusive. The Place Names of Devon gives no mention nor do the other English Place Name books, apart from suggesting that similar names with the pinch element could either be the Old English pinca which means finch or Later English pink meaning minnow, Ekwall, 1980, p.367. Sousson’s Plantation was previously a rabbit warren so there is a possibility that it was a early field name, Field, 1989, p.167 considers that field names with the pinch element refer to “derogatory names, ambiguously referring to parsimony and torture. The name clearly existed in 1888 as the Ordnance Survey map below shows:

Bibliography.

Crossing, W. 1990 Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor, Peninsula Press, Newton Abbot.

Ekwall, E. 1980, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Field, J. 1989 English Field Names, Sutton Publishing, Gloucester.

Hemery, E. 1983 High Dartmoor, Hale, London.

Woods, S. 1996 Widecombe-in-the Moor, Devon Books, Exeter.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor