“Evil Combe – Steep valley edges drop to boggy ground that the sun doesn’t touch, and where nothing but heather dares to grow. The wind, exhausted from its long journey across the moors, howls like the great wild dogs that are rumoured to roam these parts. Some believe the devil himself dwells there. They say he lures unsuspecting hikers from the safe paths above by taking the form of a lame sheep or a lost child. Then he drags them down into the bog below, their calls for help drowned by the wind and the devil’s laughter. They disappear from view, never to be seen again. Sometimes on a rare, calm day, you can still hear the screams. But these are all just rumours. The only ones who know the real reason for the name Evil Combe are the dead.” – Melanie J. Kirk.

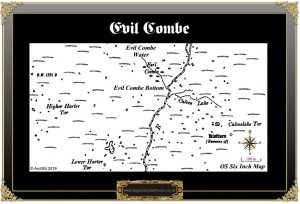

Evil Combe – probably not the most inviting place to visit as the above suggests. it’s boggy, tussocky and drear to say the least. But all that as may be the little combe is still evidence and tin mining on Dartmoor. The question is – why does the name allude to some unknown diabolical event? Did/do the forces of evil dwell there? Was it the scene of an horrific murder? Well in reality the place-name association is completely innocent. There are two suggestions as to the etymology of the name, the first one relates to the mining activities that once took place in the combe and surrounding area. The English Place-Name Society states that in a deed of 1611 it appeared as Great Evell – p.239. Hemery expounds a bit further by suggesting that the ‘Evell‘ element had derived from the old name for a miner’s iron pick, which sounds logical – p.194. Whereas William Crossing takes a much earlier view of the element by saying the name came from the word ‘ivel‘ meaning ‘little water’. – p.434. With regards to the combe itself Crossing also considers that it was once part of the lands given by Isabella de Fortibus to Buckland Abbey. In the charter it was listed as Plymcrundia ad Plymma – crunia then mutated to ‘crundle’ denoting a spring or well. – p.433. On the other hand Clarke Hall defines ‘Crundel‘ as being either a ravine or quarry. – p.75. So ‘spring’, ‘well’, may apply to Evil Combe Water which rises in the combe or ‘ravine’, or ‘quarry’ could allude to either the combe or the old tinners workings which may be mistaken for quarrying activities?

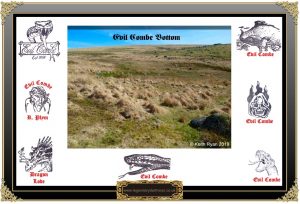

So in all reality what has left the landscape we see in the combe today and why? Basically it’s a mixture of man’s mining activities and nature which has created two mires along with a variety of vegetation which has now covered up much of the evidence of tin mining. For example there is a miner’s cache or ‘beehive’ hut that was used fro storage/shelter and the remains of which have virtually been lost to, the term gives me shudders, ‘re-wilding. In 1902 T. A. Falcon stated in the Devon Notes & Queries publication that there was a beehive hut in Evil Combe – “Remains of a beehive hut in Evil Combe, between Harter Tor and Calveslake Tor, where the general mining debris is extensive. The walls of this hut are still standing to 4 feet 6 inches; its diameter, 3 ft from the floor, is 5 feet.” Both William Crossing and Eric Hemery also mention the beehive hut being in-situ in their books and as can be seen HERE the Dartmoor Archive have a photograph of the hut. However a English Heritage Field Investigator argued in 1978 that; ” No trace of this hut could be found. It may be that it has totally collapsed since Falcon’s note of 1902 and, if so, it will appear little different from the rest of the mining debris in the area.” Similar findings were recorded when another English Heritage Field Investigator visited the combe in 2002. John Robbins mentions the remains of a leat that once supplied a reservoir at the Eylesbarrow mine; “There is documentary evidence to show that this leat was dug in 1816. Even so little difficulty will be experienced in following it as it makes a long sweep around Higher Hartor, first south, then east, and now North to Evil Combe.” – p.123.

Amazingly I can find hardly any record of any folklore legend or tales connected with Evil Combe apart from a brief mention of a dragon. Amongst details depicted on an early 19th century plan of the Eylesbarrow mine are two parallel lodes quaintly designated as ’North Dragon Lode’ and ’South Dragon Lode’. Against the latter, where it crosses the extensive Evil Combe streamwork, is an intriguing note stating ; “a fiery dragon was seen to fall near this place“. This is referring to Evil Combe where it has been said that the ‘dragon’ used to visit to slake its thirst in the waters. Or could this possibly have been a sighting of a meteor landing near the combe?

As once can imagine Evil Combe was at one time an inspirational location to use as the subject for letterboxers and as can be seen above most had a demonic or a ferocious looking snake illustration. That is apart from the one that depicts a combe with an otter in it.

![]()

Clark Hall, J. R. 2004. A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crossing, W. 190. Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor. Newton Abbot: Peninsula Press.

Gover J. E. B. et al. 1992. The Place-Names of Devon. Nottingham: The English Place-Name Society

Hemery, E. 1983. High Dartmoor. London: Robert Hale.

Robbins, J. 1984. Follow the Leat. Devon: J. Robbins.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor