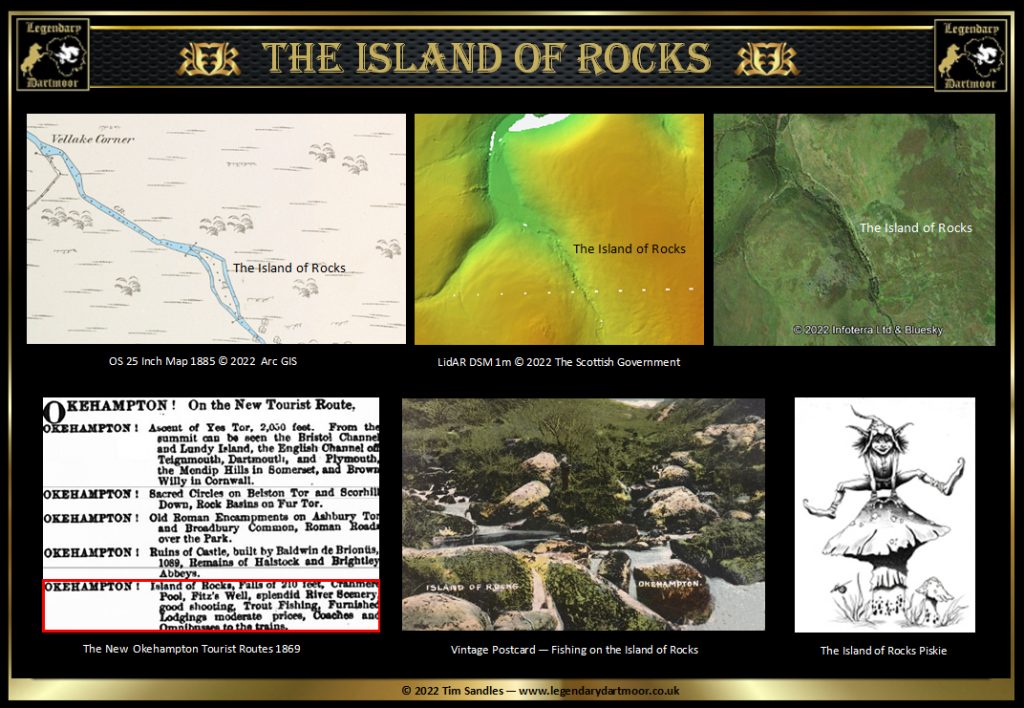

Without question there are numerous picturesque and magical places on Dartmoor. Over the years such places have come and gone out of vogue. Tavy Cleave has always been a favourite as has the Fingle Gorge. One that seems to have slipped down the league table is the West Okement Valley. Since the mid 1800s the West Okement Valley was promoted as one of the local attractions and the ‘star of the show’ was the Island of Rocks. You can see below that in 1869 the town of Okehampton were advertising several “New Tourist Routes,” one of which was along the West Okement with the first port of call being the Island of Rocks’. The other factor that led to its popularity was that the Island was located on this recommended and well-trodden route from Okehampton to Cranmere Pool. Back then it was a small rocky island in the river just above Vellake Corner below Homerton Hill which was covered with small trees and undergrowth. It was a favourite spot for picnic parties, fishing, flowers, and birdlife and like any such places it had its own folklore and a tragedy attached to it. What follows are some gleanings from various books and newspapers of the time which all describe the picturesque beauty of the island.

“Near the foot of the glen the river divided at a cigar-shaped island; closely confined between Shilstone Tor and the one side and Homerton Hill on the other.. Where the valley side track passes through a granular clitter the river has over the ages piled up boulders at the foot of the falls, then cut into its bed on either side of the obstruction, leaving a boulder-strewn strip in mid stream known as ‘the Island of Rocks.'” – Miss Sophie Dixon, 1830.

“Picnic Party – On Tuesday, about fifty from North Tawton and the neighbourhood, held a picnic on the Island of Rocks in the West Okement. It is gratifying to find that at last one of the most lovely and romantic portions of Dartmoor is becoming more appreciated. Cawsand beacon has been the favourite resort for picnics, but any lover of wild and picturesque scenery will pronounce the West Okement Valley to be unsurpassed if equalled by any portion of Dartmoor.” The Western Times, July 22nd, 1870.

“Now, although the beauty is slightly marred by a fire which raged in June last (1887) in the lower portion of the isle, the work of a too careless smoker, it is a glorious sight. The river in about a quarter of a mile makes a descent of at least 150 feet, and in the midst of the fall is split into two parts – the whole of its course and the island so formed is a mass of huge boulders, covered with richly foliaged stunted oaks and mountain ash, to say nothing of the ferns, bracken, and whortleberry bushes which grow in great profusion. This morning the sight is more than usually charming the water is high, the mountain ash are laden with the coral berries and already the autumn tint is showing on the foliage, and as if to add another pleasure to the scene, blackbirds, thrushes, and the ring ouzels flit in and out of the bushes, disturbed by our approach” – The Exeter & Plymouth Gazette, October 15th, 1887.

“Down in the valley on our right is the most beautiful Island of Rocks and we have struck almost the head of Woody Gorge. It is indeed a most lovely spot – the hill we have come down is a rich mass of golden bracken and brighter gorse, while at our foot the moorland stream – the West Okement – makes its rapid descent through masses of grey lichen-covered boulders, with oak and beautiful mountain ash growing in profusion. It is indeed one of, if not the most picturesque and charming glens on the Moor; but strange to say, not referred to or mentioned in the otherwise useful and correct work, “The Perambulation of the Moor,” by the Rev. Rowe, which no lover of Dartmoor should be without.” – The Devon & Exeter Gazette, November 10th, 1887.

“Just before reaching a level amphitheatre in the hill, it (West Okement) encircles an island where dog rose, alder, and honeysuckle, mingling with mountain ash and osmunds regalis (Royal Fern), create an oasis in the desert; while granite masses, which must even here intrude their presence, give to the islet an appearance at once rugged and picturesque, and confer upon it the name of the Island of Rocks.” – J. Ll. W. Page, 1895, An Exploration of Dartmoor, p.71.

“The Island of Rocks is about one hundred and twenty yards in length and about twenty-five yards in breadth. It is placed at the lower end of a narrow, rugged defile, through which the Ockment runs, descending nearly two hundred feet in a distance of between three and four hundred yards. The island is entirely covered with trees and undergrowth, as also is the eastern bank of the stream. There are only a few boulders near its lower end left unconcealed, and these are heaped in the manner of a tiny tor.” William Crossing, 1905, Gems in a Granite Setting, p.43.

In the January of 1866 and inquest into the death of 50 year old Richard Allen was held in Princetown. He had left his home at Sourton in order to go to Sticklepath and decided to take a short cut across the moor. The following afternoon Mr. John Gard from nearby Youlditch was out gathering sheep when he was alerted by his dog at something close to the island of Rocks. On inspection he discovered Allen’s dead body sat under a rock with an umbrella at his feet. It was assumed that he had taken refuge under the rock from the previous night’s storm where he died from exposure and fatigue. The jury returned an open verdict.

In the September of 1889 two male tourists visited the Island of Rocks, as it was a hot day they decided to take what today is called a “Wild Swim”. One man had taken off his clothes and was about to take a dip when the other said he had found a better place upstream a bit. So having gathered up his garments the former man rejoined his friend. Having enjoyed their refreshing bathe the men began to don their clothes when the first man realised he had left his waistcoat back at the original spot. In the pocket of the waistcoat was a gold watch, the gift of his deceased father, worth £60 along with £1. 10s. in gold and other valuables. Despite an exhaustive search there was no sign of the waistcoat and they assumed it had fallen in the river. The next day the men found one William Way of Okehampton who was well acquainted with the West Okement Valley. He was consequently employed to return to the Island of Rocks and continue searching for the waistcoat. After searching for a good three hours or more he was about to give up when he spotte3d something glistening in about four feet of water. He fished the object out and saw that it was the missing gold watch which luckily was attached to the waistcoat by its chain. Having returned the watch, gold coin etc. to the men he was rewarded with £3.

The Island of Rocks was once considered to be a place where the piskies held their nightly revels. One dark moonlit night an old poacher was out looking for some game for his supper. Unfortunately his search was futile, and he resigned himself to a meagre meal of bread and cheese. Just as he was about to trudge home he noticed some movement in the undergrowth of the Island of Rocks. Slowly he crept over to where it was coming from and much to his delight he spotted a large puss hare. He sprang of the hare, grabbed it, and stuffed it in his sack. As he made his way home he suddenly heard a shrill voice calling out “Jack How! Jack How.” The voice began to come closer , constantly calling “Jack How! Jack How.” Immediately his hare began to squirm and wriggle in his sack and another even shriller voice from within the sack shouted “Ho! Ho! there’s my daddy.” The old poacher opened his sack to see what was going on when immediately a little piskie shot out and ran towards his “daddy. The old man was speechless, not only had he lost his supper but also the chance of making the piskie reveal where his treasure was buried.

In the August of 1917 a mighty thunderstorm crashed its way across Dartmoor and Mr. R. H. Worth was caught out in it. He had the opportunity of “seeing the remarkable rise of the flood waters on some streams such as the Redaven, Fishcombe and Vellake which feed the West Okement… On setting out in the morning some of these smaller streams could be easily crossed by foot, but after the torrential downpour of rain it was necessary to make long detours to return. Great masses of material, consisting in some cases of boulders weighing several tons had been transported considerable distances.” – The Western Morning News, February 22nd, 1926. All of these streams are just downstream from the Island of Rocks. According to Eric Hemery during this storm “every boulder on the Island of Rocks was covered by the river and water streamed down Homerton Hill in sheets.” – High Dartmoor, pp.903-4.

It has been awhile since I last visited the Island of Rocks and sadly many of the above descriptions can no longer be seen as much of the vegetation and tree growth have disappeared.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor