If a tor could talk then the one with the best story has to be Longaford Tor, sitting proudly on a moorland ridge the granite pyramid overlooks extensive vistas that over the millennia have been home to man. The granite outcrops have witnessed passing bands of Neolithic hunter gatherers in search of food, later they quietly watched the early Bronze Age settlers building their settlements on the slopes below. Down through the ages numerous travellers have trudged by the tor, some sombrely taking their dead along the Lych Way, others wending towards the old tinners parliament rock on nearby Crockern Tor. Each one has left their time worn marks scattered around the rocky eminence for us to ponder upon – so let’s us ponder…

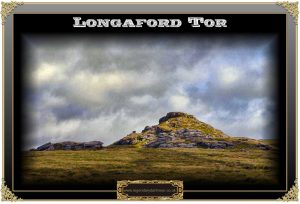

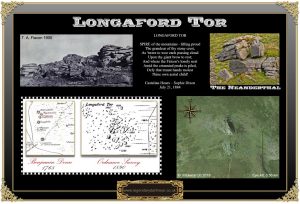

The actual tor itself sits majestically at a height of 507m (1,663ft) metres and consists of two outcrops of granite, in a cartographical context it displays the unusual feature of having grown in height. In 1890 the Ordnance surveyors recorded the height of the tor at 1,595 feet (487m) but later revised their calculations and increased it by 69 feet (20m). This brings to mind the 1995 film called, ‘The Englishman who went up a hill, but came down a mountain‘, in which some Welsh villagers wanted the surveyors to increase the height of their local hill in order to classify it as a mountain.

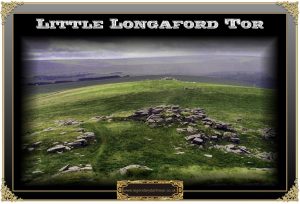

As the tor consists of two outcrops they have been given two individual place-names to avoid confusion, the northern pile is referred to as Longaford Tor and the smaller, southern mass as Little Longaford Tor. At first the meaning of the name ‘Longaford’ seems fairly clear – the ‘long ford’. However, the nearest fording point is the Wistman’s Warren Ford on the West Dart River which lies about half a mile to the north west? Even more confusing is that on Donn’s map of 1765 the tor is recorded as Southbeetor (see map below), Hemery, considers that the place-name element of be alludes to the, ‘passage of an important trackway‘ –p.424 fn, such as the Lych Way which passes nearby. This would then give the name of the ‘tor with the way to the south’ or some similar combination but how the name later became Longaford Tor is puzzling. A possible answer lies in the Welsh word fford which relates to an ancient trackway, again possibly the Lych Way.

Many writers have described the tor and most seem to agree on one common descriptive, namely, ‘conical’. The following extract was given by the indomitable Mrs Bray: “Longaford is more conical than most of the eminences of the forest, having very much the appearance of the keep of a castle. Unlike also the generality of tors, which mostly consist of bare blocks of granite, it has a great deal of soil covered with turf, and only interspersed with masses of rock, whilst the summit itself is crowned with verdure.” – p. 121.

Some 40 odd years later the intrepid Dartmoor explorer, William Crossing visited the tor and penned the following description: “This tor, which is a very prominent object for a great distance around, is situated on the hill to the eastward of Wistman’s Wood, and is of a conical form, presenting a very striking appearance, from whichever side it is viewed. We clambered up its precipitous sides, and on the summit, where there is a tiny plateau of fine grass we spread our luncheon, and while discussing it, also feasted our eyes upon the attractive expanse of moor which that elevated spot commands. Many and many a tor is to be seen from Longaford, and immense stretches of wild heath and fen on every side.” – p.86. Scattered all around the western flanks of the Tor are the vestiges of the old Wistman’s Warren, an early nineteenth century sporting rabbit warren once belonging to James Saltoun.

On the south-western side of the tor is a convenient rock shelter above which a small rowan tree bravely clings and in itself is a wonder that such a plant could survive in such a place. Just above here on the lowers grassy plateau silently sits the rock formation known as the ‘Longaford Neanderthal’ which is ironic as it stares out over the old Bronze Age settlements

Longaford Tor has appeared in several Dartmoor novels, Eden Phillpotts’ ‘The River’ and ‘The Farm of the Dagger’, Marjorie Deboer’s story of ‘The Whitbourne Legacy’ and Miranda Cameron’s book ‘The Undaunted Bride’ to name but a few.

Longaford Tor has over time been the home and haunt of many of Dartmoor’s denizens of the animal kingdom, at one time the raven nested on the tor which is what Sophie Dixon alludes to in the extract from her poem above. Look any any of the old fox hunting reports of yesteryear and you will see Longaford was a favourtite place for foxes to built their lairs among the granite rocks. On a more recent note (June 2008) a mystery ‘beast’ was spotted on Little Longaford Tor which could possibly have been a puma – see The Beast of Dartmoor page.

Having mentioned the foxes of Longaford it would be remiss to omit the tale of the Ghost Foxes of Dartmoor who are said to haunt the rocky outcrops today. Many years ago a moorland shepherd ventured out onto the moor one winter’s day and was known to be heading out over Longaford way. That night a dreadful storm swept across the moor and for whatever reason the shepherd never returned home and was never seen again. The following spring a grim discovery of a human skull and bones was made outside a foxes den on Longaford Tor which was presumed to be the last mortal remains of the shepherd. It is said that each year during the week proceeding Christmas the ghostly cries of phantom foxes can be heard on and around the tor.

Bray, E. 1836. Legends, Superstitions and Sketches of that part of Devonshire on the Borders the Tamar. London: Murray.

Crossing, W. 1974. Amid Devonia’s Alps. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

Donn, B. 1965. A Map of the County of Devon. Exeter: Devon and Cornwall Record Society & The University of Exeter.

Hemery, E. 1983. High Dartmoor. London: Hale Publishing.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor