Cranmere Pool – “A hundred years ago, this spot, so familiar to every Dartmoor wanderer today, was shunned as a place of evil omen, and not a moorman would willingly have braved the supernatural perils of the place alone.” – Eden Phillpotts, The Master of Merripit Farm.

Cranmere Pool or as one suggestion for the place name has it – ‘The Lake of Cranes‘, does that not conjure up an idyllic picture of a tranquil lake situated on the high moors with herons darting the fish as they swim by? Well actually what you need to imagine is a wet, boggy tract of land with possibly a pathetic muddy pond or a dried up peaty mess, depending on the rainfall. You then need to picture an ugly stone box dumped on a base of granite boulders and forget about the herons – that is Cranmere Pool. Therefore is it not surprising that such a place should have its very own miserable, moaning ghost

Back in the times when sailing ships and ruthless pirates ruled the seas a wealthy ship owner and merchant called Benjamin Gayer lived at Okehampton. He was a well known and respected business man of the area and held several seats of local power. About this time the problem of piracy on the high seas was getting serious. Not content with plundering the ships for their cargoes the pirates began taking the crews prisoners and then demanding huge ransoms for their release. To this end it was decided to start a fund from which the ransoms could be paid. In the Okehampton area the collection of money to form the fund was the responsibility of Benjamin Gayer. With his contacts it was not long before a substantial amount had been raised all of which was entrusted to Gayer. Then one day news reached him that several of his large ships had fallen prey to the pirates, both the ships and their valuable cargoes had been lost which meant he was virtually penniless. Poor Benjamin was beside himself, all his wealth had disappeared overnight. The only way he could recover his losses was to buy new cargoes and that needed money, something he no longer had. Over the following days he contacted many of his trading partners to see if they would loan him the funds but sadly they were not prepared to risk large sums in light of the growing piracy dangers. Then he remembered he had the ‘ransom fund’ at his disposal and reluctantly decided to ‘borrow’ it. He had every intention of repaying the money and even interest on top, of that there was no question. So merchant Gayer bought new cargoes and hired new ships to collect them. Sadly these too fell victim to the pirates and he lost the whole lot, this meant he was unable to repay his loan to the ransom fund. The knowledge of what he had done weighed heavy on his mind especially as it meant many seamen would now be doomed because there was no money to pay their ransoms. Gradually his health got worse and worse and his guilt slowly dragged him onto his deathbed and eventually he died a troubled soul.

It was not long after his funeral that locals reported seeing his ghost around the town, the restless spirit would wail and weep and moan and mumble all through the night. Although the locals tried to ignore the restless spirit it became that they could not get a full nights sleep. Weeks passed, months passed and still the ghost of Benjamin Gayer haunted the town. In the end the locals decided enough was enough and decided to take action. They asked the Archdeacon for divine intervention and so reluctantly he summoned all the clergy from the surrounding parishes in an effort to tackle the ghost. One by one, with bell, book and candle they confronted the spirit, they demanded he returned to his grave and lie in peace until the great day of judgment. One by one they failed in their task for although when confronted the spectre would disappear it always re-appeared the following night. The Archdeacon was at his wits end he had tasked all the available clergy and all had failed. He then suddenly remembered that there was a very learned priest living in a remote part of the moor. A messenger was dispatched with a plea for assistance. Two days later he returned with the priest and that very night the ghost was confronted. The priest took no bell or book but instead took with him a new bridle and bit and the best horseman from that side of the moor. This time the learned holy man spoke to the spectre in Arabic and said “Benjamin Gayer, the time has come for you to be gone from Okehampton and the mortal world, you must return to the grave and await your final call, the Lord shall decide the weight of your sins”. To this the ghost replied “now you have spoken in holy tongue I must depart your world” and with that immediately turned into a jet black colt. As previously instructed the horseman put the bridle on the colt and leapt onto its back. He whipped the horse and sped off onto the moor holding the reins as tight as he could to ensure that the colt could not turn its head in the direction of Okehampton. Up over stream and tor they sped until they came near Cranmere pool, here the horseman whipped the colt even harder until they were hurtling towards the murky waters. Just before the colt hit the pool the rider removed the bridle, leapt off and left his mount to dive into the cold, murky waters. The priest then appeared and condemned the ghost of Benjamin Gayer to remain banished to the pool until the time when he could empty its waters using only a sieve. For several years the ghost tried to empty the pool – all to no avail which meant the folk of Okehampton finally were left in peace. That is until the day that the ghost found a dead sheep’s carcass. This he skinned and lined the sieve with the hide which meant he could now empty the pool. This task he set to with great relish and so effective was he that the waters cascaded down the hillside and into the river Okement. The deluge rushed off the moor and flooded the whole of Okehampton which as you can imagine did not best please the townsfolk. Once again the learned priest was summonsed and dispatched off to Cranmere Pool to once again confront the spirit of Benjamin Gayer. This time the priest demanded that the ghost should make trusses of grit and that they should be bound with plaits made of sand and this task was to last until judgement day. To this day the ghost now known as ‘Cranmere Benjie’ plats and weaves his trusses and every time he picks them up they crumble back to sand. On still nights many people have heard him wailing and weeping at his misfortune. Occasionally night walkers have also reported seeing the ghost of a black colt thundering across the moor in the Cranmere area.

There are two other lesser know legends attached to Cranmere Pool, firstly, there was once an Abbot of Tavistock Abbey who had a very dubious groom called “Bingie”. One day the abbot noticed that the health of his favourite mule was failing so he asked one of the monks to spy on the groom. It did not take long for an explanation to come to light, the groom was greasing the mule’s teeth so it could not eat and was stealing its corn. Mysteriously the groom vanished and later was known to have been condemned to Cranmere Pool where he was to remain until he could empty the pool with an oat sieve. The second tale also involved an Abbot of Tavistock Abbey. It transpired that a priest from the little Halstock Chapel near Okehampton had offended the Abbot by denying his jurisdiction. After consultation with Rome it was the priest was threatened that if he did not conform then the chapel would be disestablished and the priest disendowed. However, if the priest, as a penance, were to take a sieve and line it with a sheep’s skin, go to Cranmere Pool and empty it then all would forgiven. The priest went to the pool with his sieve and fervently set to emptying it. Unfortunately he did such a good job that the rushing waters flowed on torrents from the pool as it passed the chapel the deluge carried away the chapel. So powerful was its force that it then flowed down into Okehampton and inundated the town and washed away the bridge. – The Western Morning News, April 2oth, 1868.

As previously mentioned, the marshy hollow known as Cranmere Pool does exist. It is located in a triangle formed by the heads of three rivers; the West Okement, the Taw and the East Dart. For the past 150 years or so this place has become a ‘Mecca’ for Dartmoor Walkers and God only knows why. It is said that in a good year it will rain 200 out of the 365 days in the Cranmere area which is why in the January of 1931 the Meteorological Office placed a rain gauge at Cranmere which was monitored on a monthly basis. At the time they requested that the public “not interfere with the apparatus.” Unfortunately by 1933, “The Observer reports interference with the apparatus at Cranmere Pool and states that attempts have evidently been made during the past month to wrench off the locking equipment, which was placed on the gauge last year following discoveries that the container had been tampered with on several occasions.”

In really wet conditions the only way to cross it is to ‘bog hop’ from tussock to tussock and if you get it wrong expect a good, stinking soaking. I recall one October night having to cross from the end of Blackhill peat pass to Hangingstone Hill in the dark, which is only about 2 miles. It was lashing with rain and the whole area was sodden. The walk actually took 3 hours and believe me if that was not enough to put one off Dartmoor for life I do not know what is. The actual ‘pool’ is located at a height of 1,837ft (560m) in a very well hidden hollow. I have known people that have been unable to find it when in fact they had walked within 20 yards of it. If you ever go to the pool, read the visitors book and see how many people have “finally found it” after varying numbers of attempts. I also recall being there on the day of Princess Diana’s funeral and there was not a soul to be seen, very strange feeling that day.

Cranmere Pool was once filled with water, as mentioned early the name Cranmere was thought to have come from the Crane Mere as Crane was the Dartmoor term for a heron and mere is pool. However, Gover et al, 1992, p.193., suggest that the name actually derives from the 1695 Britannia which calls it Crau Meer or Cran Meer indicating ‘Crow Mere‘. Hemery considers that as there was once water in the pool there may have been fish and therefore it was possible that herons would hunt here. Cran Mere Pool is show on Donn’s map of Devon drawn in 1765. Many early topographical writers note that from the late 1700’s to the mid 1800’s the pool was full of water. Hemery, 1983 pp 893-5, says how Mrs Bray in 1832 considers the pool to have been about 6ft in depth. Other estimates vary from 5 – 6ft and covering about 200 yards. It is possible that the pool was partly drained in 1789 when the writer John Andrews visited and was certainly empty by 1844 when Samuel Rowe was there. Some sources say an old moorland shepherd drained the pool because it was a danger to his sheep, another theory is that a local hunt breached the bank when digging a fox out. It has always been said that it is impossible to ride a horse right up to the pool, the nearest anybody has come to it was George Collier who in a very dry year got to within 100 yards of it. In 1936 the Western Morning News published the following report; “Sir – Yesterday I saw four horses at Cranmere Pool, which must be a rare occurrence, though formerly it was said that the spirit of an Okehampton mayor haunted the place in the shape of a black colt. One horse was actually standing by the post box though its rider had considerable difficulty in getting the animal over the gullies of soft black peat at the head of West Okement. The adventurous party of men and girls has ridden by way of Cocks Tor, Walkham Head, Fur Tor and Phillpotts Cutting through Black Ridge. – Moorover, St. Marychurch, Torquay.” The Rev. Hugh Breton mentions how George French of Postbridge used to take visitors to Cranmere Pool and in the June of 1912 he went with him. They travelled there sat in the bottom of a cart which went passed the Grey Wethers, up to Sittaford Tor and across the headwaters of the North Teign river up to Whitehorse Hill. From here the horse was tethered and the rest of the journey was done on foot, p.99. For anyone who knows the area it was no mean accomplishment to drive a horse and cart from Sittaford across to Whitehorse Hill.

So, what can you see at Cranmere Pool? Well the first thing you will see is the largish granite box that contains one of the three officially recognised Dartmoor Letterboxes, the other being Duck’s Pool. By that I mean it is actually marked on Ordnance Survey maps. Many of the early topographical writers were none to impressed with the place, for instance Samuel Rowe considered that; “We shall find nothing to detain us in the Cranmere morasses…“, p.94. Baring Gould paints the following picture; “Cranmere Pool may be reached, but is only so far worth the visit that the walk to and from it gives a good insight into the nature of the central bogs. The pool is hardly more than a puddle.“, p.149. Such is the desolation of Cranmere that St. Ledger-Gordon recounted a time when he took a man from Nairobi to the pool. Whilst crossing nearby Tavy Head the man announced that he had never experienced such solitude, even in the jungles of Africa. There at least he would have eventually come across a goat herder or a small village – at Cranmere there was nothing or nobody which would suggest human activity or life, p.241.

Cranmere Pool is also the birthplace of Dartmoor Letterboxing, in a nutshell, letterboxing was originally a Dartmoor phenomenon whereby a rubber stamp with some sort of design on it and a visitors book are placed in a container and hidden. Triangulation bearings are then taken for the spot where the box is hidden these then form the clue along with a few more helpful pointers such as; under a lone boulder, 5 paces from a upright rock. The clues are then circulated amongst other letterboxers who then go out and try to find the hidden box. Once found a copy of the rubber stamp is taken and the visitors book duly signed to verify the fact that they had indeed been there. So why should this all begin at Cranmere Pool? Well, in the 1850’s it would have been about an 16 mile walk to get there and back so visitors would get to walk into the heart of the moor and thus experience the true landscape. It soon became the ‘in thing’ to do when visiting the moor. As mentioned, Cranmere can be a difficult place to find and a boggy place to reach so in this light a few enterprising moormen took to guiding people to it. Hemery gives record of an unknown visitor to Cranmere in 1789 who hired the services of a local guide to take him there for the princely sum of 6d, p.895.

In the August of 1938 there was an initiative set up by the West of England Ramblers Association whereby anyone visiting the elusive Cranmere Pool could receive a certificate. As getting to the pool and actually finding it was considered quite a fete the certificates were a nice memento of the occasion. It appears that news of this opportunity spread fast and soon qualifying ramblers began applying for their award. However, there was a slight hitch insomuch as when the Association received their first batch of certificates there was a problem with the printing, and it was rejected. A backlog of applications soon grew, and disgruntled ramblers began to complain via local newspapers. The intrepid Fredrick Symes, aka Mooroaman, was amongst the most vociferous, so much so that the Hon. Secretary of the Association, Mr. Harold Overton, published a public apology over the delay and assured Mooroaman that his newly printed certificate was in the post. As can be seen below the certificates were nothing fancy but nonetheless a memento of one’s visit to the pool.

In the mid 1800s another local providing such guiding services was James Perrott of Chagford. He would take anyone on the 16 mile round trip from Chagford to Cranmere ensuring the safest and driest route. It soon became an accomplishment akin to the modern day Snowdon or Ben Nevis experience. In later years, on the return journey they would call into Teignhead Farm for a well earned Devon tea which was provided by the formidable Mrs Brock. In 1854, Perrott decided to leave a large stone jar on top of a cairn at the pool so visitors could leave their calling cards in recognition of their visit this was known locally as ‘dropping a card on Binjy’ (Benjamin Gear). The original stone jar had a cover on it which was inscribed with some names and the words; “United Ages 420 – 1891.”, it is thought this originally came from a burial ground – see picture below. Future visitors could then see who else had been there previous to them. This idea evolved to include a proper visitors book where people could leave comments of their visits and so in 1903 a tin box containing a visitors book replaced the stone jar. This soon rusted out and in 1905 a zinc box was used. The increasing popularity of people visiting to pool can be seen from the numbers in 1911. January – 12, February – 17, March – 22, April -180, May – 169, June – 175, July – 276, August – 424, September – 431, October – 155, November – 6, and December – 0, giving an annual total of 1,877. These figures were based on the number of entries in the visitor’s book.

In 1912 a Mr. J. W. F. Rowe constructed the first solid ‘postbox’ which had to be transported on a sled to Cranmere as it was so heavy, this being the forerunner of the modern structure, Hemery, p.895. In 1935 the Western Morning News carried an article written by the Rev. J. P. Baker which read: “… I was concerned at getting to Cranmere the other day to find the box provided by our old friend H. P. Hearder, in 1905, was breaking up, and that the bank in which it had reposed in its casing for so long was almost washed away. I was very glad to see that The Western Morning News still very generously provides a visitors book, but the pad for the postmark has long ceased to function. The best I could do was to moisten the stamper from a fountain pen.! I noticed a few coppers and stamps in the box, which I gathered from remarks in the book had been left as a first contribution towards an new box.” According to St. Ledger Gordon another ‘permanent’ post box which was made from granite was sited at Cranmere under the auspices of the Western Morning News in 1937. This version was constructed by one Aubrey Tucker and an official ceremony took place when St. Ledger Gordon’s wife unveiled the postbox in front of various guests, p.241. The Cranmere postbox also suffered a great deal of damage during training exercises during the Second World War when it was actually hit by shellfire. Over the years the post box has undergone many stages of refurbishment, the latest being in 2014 when the door was repaired by applying several layers of paint in the hope that it can withstand the vagaries of the Dartmoor weather for a few more years. Records taken from the early visitors book show that in 609 people signed the book in 1905, 962 in 1906, 1,352 in 1907 and 1,741 in 1908. In either 1910 or 1912 a more weatherproof ‘post box’ was installed. This had to be transported on a sled due to its weight. The pool received a royal visitor in the form of Prince Edward, he visited here in 1921 and signed the book, which incidentally allegedly got stolen a few days later. The was a great deal of press coverage about the theft with autograph hunters taking the blame. However a short while later it was reported that Mr. J. E. Heath, a solicitor from Plymouth (he was in charge of the subscriptions for the upkeep of the box) ordered its removal as he feared that the page with the signature or the entire book would be stolen. The book was then returned to him with the intention of placing it in the Plymouth Library along with the previous visitor’s books. Both the visitor’s book and post box were the subject of protest in the August of 1913 when some suffragettes visited Cranmere. They left a copy of ‘Suffragette in the post box and wrote in the visitors book; “Hurrah for Mrs. Pankhurst, Christabel, and all the brave women of W.S.P.U”

On Saturday 8th May 1937 a new robust box was officially opened. This box was built by an ex tin miner called Aubrey Tucker, it was constructed of granite with an oak door. The money was raised by an appeal made by the Western Morning News. It was sometime in the 1960’s that the first letterbox stamp appeared at the pool.

An early Cranmere Pool letterbox stamp.

Due to possible souvenir hunters, the Dartmoor weather and other variables it can be hit or miss as to whether the stamp and or the visitors book are in-situ. In 1938 the Western Morning News reported that they had supplied a ‘new’ stamp for Cranmere Pool which was taken out there by Mr. R. Harry of Okehampton. At the same time the Post Office renewed the inking pad and ink at the letterbox. It appears that this one did not last long for back in the the August of 1940 the Western Morning News published the following plea for help: “An anonymous correspondent having discovered that the rubber stamp at the Cranmere post-box is damaged, has sent from Birmingham a new stamp with ink pad. Would any of the Cranmere trekkers care to complete the good work by taking the rubber stamp to the pool?”

Another tradition that has grown up is that if a self addressed and stamped letter or postcard is left in the letter box the next visitor will usually take it home and post it. I have always had every one returned that I left there, some postmarked Scotland and even one Belgium. The visitor book collection is housed at the Plymouth museum and makes for interesting reading. As but one example of this practice and its popularity, MooRoaMan writes in 1933; “Accompanied by a quintet – two hikers, three hikresses – clock round circular tour was made via Lydford Junction to Okehampton and back to the former by way of Great Kneeset., through Hare Tor rock field, past Willsworthy Butts, leaving Henscott Plantation to the right. At the pool was the champion Cranmerean on his 219th visit! Fifty four names in the visitors’ book made up the Bank holiday’s total, several being Tottenhamites. The weather and going conditions were as favourable as I have known in my twelve years of Cranmering and what a Mecca the elusive and delusive pool unaccountably remains, one ‘mail’ totalling over six score postables! bearing the more or less erratic ‘Cranmere’ postmark.” In the early September of 1929 a man from Plymouth visited Cranmere Pool and left a postcard addressed to the Dartmoor authoress Beatrice Chase (AKA Katherine Parr) and strangely enough on the following day the next visitor to the postbox was Beatrice Chase herself. On this occasion she was accompanied by James Perrott and described how the tin box which she called ‘Bingie’s Box’ was hauled out from a peat bank and it was the old man who found the card addressed to her. She also left a pile of cards of her own along with a signed photograph and at the time the ruling was that no cards were to be posted until the following day. Just after she had left an ‘honourable gentleman was the next visitor and although he dearly wanted the signed photo he had to leave it. A friend of his then communicated the fact to Beatrice Chase who sent him one as consolation. She actually commented that it was; “Frightfully conceited of me to think that anyone would care for my signed picture of course, but the British public is so sweet about my silly schemes, and plays up to them so admirably! My visitor told me that his friend saw my pile and the inscribed picture in Bingies Box and wanted it so dreadfully that he had a sharp struggle with himself and remarked bitterly, “That’s always the reward for being honourable.”… He does not know that his friend has told me the story, so toady I have posted, another card, a signed portrait in Bingies Box addressed to the gentleman, and bearing the inscription “To the still More Right Honourable Gentleman, who played the game on September 7th, with admiring greetings from MY Lady of the Moor.””

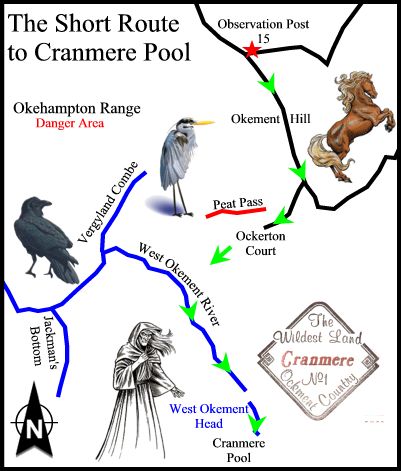

Today there are many routes into Cranmere Pool, there are the original 8 milers or by using the military road this can be shortened to about a mile and a quarter. In the July of 1921 a mysterious red flag mounted on a 6ft pole appeared in the centre of the pool, presumably as a guide to those seeking its location. The cards and letters left for the next ‘postman’ read “written under the red flag.” A newspaper article from 1933 relates an early morning visit to Cranmere Pool by the legendary MooRoaMan alias Fredrick Symes: “MooRoaMan of Launceston, the well-known letter writer to The Western Morning News on Dartmoor subjects has just paid an early morning visit to Cranmere Pool. From a postcard sent from Cranmere, the editor learns that MooRoaMan was at Okehampton Camp at 1.30 a.m., reaching Yes Tor half an hour later, when the cap of High Willhays was shrouded in mist. By 4.30 a.m. he had reached No. 15 splinterproof (OP 15), on the artillery ranges. The moon was visible at 3.50 a.m. , as was a fine stellar display, including the Pleiades and Orion. The sky, however, was overclouded, and mist was collected in the banks across the moor. East Okement farm was reached at 6.30 a.m. MooRoaMan reports that there had been 15 visitors at Cranmere including five Launcestonians, one of whom had not been there for thirty years. Among the signatures in the book were those of six Bristolians.“

The 1920s saw the advent of more advanced motor vehicles which were capable of travelling along the military roads which brought visitors to within a mile or two of the pool. In 1933 The Western Morning News even published a detailed route guide for drivers to get their cars within striking distance of the pool. Over the coming years many people took the opportunity of easily reaching Cranmere by car. In a sense the pool soon became a ‘honey pot’ for visitors and locals alike all seeking the ‘Mecca of Dartmoor’ and the chance to sign the book. As the popularity of visiting Cranmere Pool rapidly grew, so did the age old problem of litter. In 1937 one comment left in the visitor’s book read “More orange peel, broken glass, cigarette cartons, film cases &c. even than usual. I suppose we owe this to the motor road which comes so near the pool. Why not move the box and book to Cut Hill or Mis Tor, and make people walk to it. In the same year J. W. Malim (alias Moorover) wrote a letter to The Western Morning News saying “Last Sunday I buried four large bottles, in addition to several large splintered pieces of glass in a small shell hole in Cranmere Pool. There was any amount of paper about Okement Hill.” In 1952 Lady Sylvia Sayer complained to the Devon Planning Committee that she has spent an hour at the pool burying broken bottles and other litter. In exasperation she had suggested to the committee that an ‘anti litter’ sign be erected at the pool a proposal to which they agreed and such a notice was duly attached to the postbox. Interestingly enough Lady Sayer attributed the growing visitor numbers and ‘abuse’ they caused down to the fact that people were getting paid holidays. A similar thing happened during the Covid pandemic when people were getting ‘furlough pay’ and visiting Dartmoor in greater numbers. On 1957 Okeridge Motor Services Ltd. made an application to The Western Area Traffic Commissioners to establish a bus route for a 32-seater coach to run from the Moor Gate along the military road. The County Council on behalf of the Dartmoor National Park Committee objected to the application. In their view “passenger service vehicles on the road beyond Moor Gate would create conditions of danger and would certainly inconvenience other road users by car and on foot.” It was also expressed that “Cranmere should be preserved as a place one found by exploring and not turned into a tourist resort.” The commissioner’s reserved its decision on the proposal.

Dense mist and quaking bogs were not the only perils early visitors to the pool had the endure. In the August of 1893 the following report appeared in the Western Times; “The attractions of Dartmoor, on the borders where I am staying with some friends, need not be pointed out. Such mild drawbacks such as treacherous bogs are well know and can be avoided, but the public have yet to learn that in a pedestrian expedition to a grand and characteristic part of Dartmoor – a regular resort – they may be exposed to a fierce fire of artillery shell. But this was actually the horrible experience of two friends and myself a day or two since at Cranmere Pool.

From 12 to 1 o’clock we had observed shells throwing up dust on a crest of a somewhat distant hill, in consequence of which we took a careful course to the pool. At one o’clock the firing ceased when we sat down in the neighbourhood of the pool to eat lunch. At 1.30 we were astounded to hear the whizzing of shells in close proximity – the horrible noise – a combination of the twang of metal and the hiss of a serpent – rapidly increased, the shells falling all around us, sometimes as near as ten yards, and constantly at twenty and fifty yards, others passing immediately over our heads.The firing increased in intensity up to two o’clock, when it ceased. Nothing in the shape of signals or notice boards of any kind had been put up to warn the public.

The next morning my friends drove over to the Okehampton Camp, and from the information they were able to obtain it appears we were in even greater danger than we imagined. The fire of eighteen guns was concentrated for the space of half an hour on a supposed enemy at Cranmere Pool! At the end of the half an hour the enemy were supposed to have been destroyed. It was nothing short of miraculous that we escaped unhurt, the nature of the ground affording no protection, except the excrescences of the boggy ground.” As Cranmere Pool is located on the Okehampton Range it had been used for live firing exercises and in the early days there was very little warning of when these events took place. Eventually this led to the use of warning flags, range wardens, firing notices, etc to alert visitors when firing was taking place. However, despite these precautions there was a fatality which took place near to the pool in the April of 1958. A father accompanied by his son and daughter decided to visit Cranmere. When the family reached the pool they decided to have their lunch. All of a sudden there was a loud explosion at which point the son said he would climb the bank to see where the guns were firing. No sooner had he reached the top there was another explosion and the boy crumpled to the ground and sadly died shortly afterwards. At the inquest it transpired that the normal safety procedures had been ignored. George Endacott, the range clearer stated that he had seen some people at the pool and immediately asked the major in charge of the exercise to cease firing – which it did. But then after five minutes or so it resumed, the result being the death of the 15 year old boy. It transpired that despite the fact that the red flags were flying along with 48 warning signs dotted around the range the family went to Cranmere because they had seen other people heading in that direction. A verdict of ‘death by mis-adventure was returned.

There was a time when to take the shorter route you simply followed the military road out to Observation Post 15 (SX 6113 8733) then head down the track to Ockerton Court. At the end strike south west until you meet the West Okement river and then follow that up to Cranmere Pool. As with any moor walk it is important to have the correct walking kit including map and compass. This area is also in the Okehampton Firing Range so it is vital to check the firing times before setting out.

PLEASE NOTE: The above route is no longer possible thanks to the closure of the military road. I have left it on this page for old time’s sake.

Such is the fame of Cranmere pool that there is now a variety of Garden Pink called ‘Cranmere Pool’, it’s described as, “A creamy white double with a deep magenta centre, producing neat bushy plants and sturdy short stemmed flowers”.

Barber, C. 1994 Cranmere Pool, Obelisk Publications, Exeter.

Baring Gould, S. 1982. A Book of Dartmoor. London: Wildwood House Ltd.

Breton, H. H. 1926. The Heart of Dartmoor. Plymouth: Hoyten & Cole

Gover, J.E.B., Mawer, A., & Stenton, F. M. 1992 The Place-Names of Devon, English Place Name Society, Nottingham.

Hemery, E. 1983, High Dartmoor, Hale Publishing, London.

Rowe, S. 1985. A Perambulation of Dartmoor. Exeter; Devon Books.

St. Ledger-Gordon. D. 1950. Devonshire. London: Robert Hale Ltd.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Walked to the pool with experienced walkers. Fog descended. Fortunately, their map and compass got us to the pool. Later, the fog lifted on the return.