High up on the north moor lies what was probably one of the remotest of the old Dartmoor tin mines. Today all that remains are some ruins, spoil heaps, and if you look very carefully a small, overgrown, reedy, gully that slopes down from the side of Okement Hill. Nearby is a well trodden track that crosses the river Taw at Knack Mine Ford and then leads up to Hangingstone Hill. So if everything is so insignificant why bother devoting a web page to it? Admittedly there are numerous other larger mines on Dartmoor with a wealth of information about them but I always favour the quiet, unassuming things in life and Wheal Virgin is one of them.

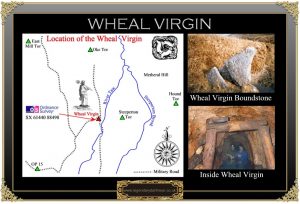

If you walk to the Steeperton branch of the military road and strike off across Okement Hill in an easterly direction you will come across various small gullies on the flank of the hill. In one of these you may notice a large peculiarly shaped stone on which has been incised the letters W V and this is the first sign that you are entering the early bounds of Wheal Virgin, also known as Knack Mine and the Steeperton Mine.

The whole area of Taw Marsh has been worked for alluvial tin since medieval times and then re-exploited in later times which lead to the use of adits and shafts in the 19th century. Duchy Records state that in 1799 the Wheal Virgin mine was “raising tin fast,” and was owned by a company called Gill & Co, its agent was Captain Henry Banter. In 1836 a licence was granted to three men from Tavistock, Henry Prenton, Francis Prout, and John White to search for minerals on a tract of land known as Wheal Virgin. The licence was to run for twelve months at the cost of a 1/18 share or dues. The bounds for the mine were set as being; “From a certain Rock or Stone marked W V on the Eastern side of the shaft known by the name of Wheal Virgin Shaft to the length of three hundred fathoms Eastward, and four hundred fathoms Westward, being together seven hundred fathoms on the course of the lode on which the said shaft is now sinking, and one hundred and fifty fathoms north and south thereof…” The map below depicts the extent of the 1836 boundary of Wheal Virgin and has been drawn to scale from the modern OS map:

The history of the mine is rather sketchy but in 1835 there is mention of ‘nack’ mine which is very similar to the ‘Knack Mine’ that is listed on today’s Ordnance Survey map. William Crossing suggests that the name is a corruption of the nearby Ock or Oke river but a local source suggested it came from the hill to the west of the mine called Knack Hill. Alternatively there is a Cornish term of ‘knacked’ which means a derilict mine? In 1836 the Duchy agent received an application from a Wadebridge man called Powning which referred to a piece of land which had been granted to a man named Honey who had abandoned the workings. Which suggests two things, Mr Honey was in fact Henry Honey, a miner from the parish of Lydford and that by 1836 the mine had been abandoned. In 1853 a miner from Lydford called Michael Stevens was granted a one year lease for the mine which was now called the Steeperton Tor sett. A Duchy report of 1854 noted how Michael Stevens was still working the sett called Stepeltor or Steeperton Tor’ and that little work had been done. There was also a recommendation that the lease be renewed for a further year and the bounds of the mine extended to encompass around 6 square miles.

There is then no further mention of the mine until 1871 when a letter was sent to the Duchy by two men from South Zeal, Thomas White and William Holman. It requested that they be given permission to establish a sett which was 800 yards each way of the old mine workings. A similar letter was written in 1872 in which they said they were trying to form a company with a view to work the mine, nothing ever transpired.

In 1875, Richard Jeffery and Samuel Oldridge requested permission to have a licence for the ‘Steeper Tor Mine Sett’ within a larger boundary than before. By the November of that year a one year licence was granted at a rent of £5 plus 1/18 dues. In 1876 the Duchy agent visited the mine and found the place deserted and the workings in a hazardous condition. The owners duely apologised and promised to secure the workings with hurdles. Also in 1876 the mining partnership was extended to include a speculator called Charles Langley, an attorney from Chudleigh. Old papers belonging to Langley show that there was very little mining done in 1876, most of the work consisted of building, cutting rushes, thatching buildings, and timbering. It was not until the October that two men, Elias Warne and a partner, were employed for six days to work in the Shallow Level.

By 1877 there was an increase in mining activity and records show that men were working in the shallow level and a new deep level was also being worked. A crosscut of three fathoms had been driven towards the ‘Oldridge’s Lode’ and later in the year a shaft had been sunk onto this lode which was described as being ‘rich’ in ore. Also in this year the partnership bought a water wheel, stamps and other mining equipment from the Gobbett mine at Hexworthy for a total sum of £65. The Gobbet mine was about 25 miles away from the Steeperton Mine which meant a bill of £28. 14s. 0d for hauling the equipment by horse and cart.

By this time the mine must have been a very busy place with men working on building the wheel pit for the newly purchased water wheel, others constructing a water source for the power which involved a dam and cutting a ‘Lobby’ or tailrace for the wheel pit. Records show that the expenditure on the venture was astronomic with supplies coming from all over. Steel was being brought in from Tavistock, sawn timber and tool hilts were supplied from Okehampton, shovels from the Finch Foundry at Sticklepath, safety fuses, candles, and nails from Okehampton, and gun powder from Powdermills near Postbridge.

Records of 1878 show that one ton of black tin was produced and at the end of 1879 the mine paid the Duchy dues of £1. 5. 1d on ores raised. This if equated out to the lease stipulation of 1/18 would account for just over half a ton of black tin and would have given the mine a return of £25. 1s. 8d. It appears that men working at the mine were fairly well paid in comparison with other mines, the average salary for a six day week being between 18/- and £1. Some of the men would lodge at the mine for the week, which was normal practice for the Dartmoor miners, at a cost of 1/- a week. There was also overtime to be earned for staying at or ‘watching’ the mine on Sundays, this was done to protect against theft or vandalism. In those days, getting to work meant a long walk and if you were going to lodge at the mine there was only a certain amount of personal supplies that could be carried. The food must have been fairly basic and a complaint made to the December of 1877 shows how the men supplemented their diet: “I find by making enquiries that there is not many rabbits left on Belstone Tors… Those Miners at Knack Mine (are up every day killing game). There are there in fact that lot at the Mine or some of them are always poaching on the Moor. I went up to the Mine about a month agone with Mr Pedler to see if we could identify 2 fellows that we saw on the Moor with 3 dogs and one gun, we could not identify them. I never saw two worse looking men in my life I had a run about 3 or 4 miles before I could get up with them. We first saw them at the top of Taw Marsh and followed them out where the river Teign goes into Chagford and there I got up to one of them and caught hold of him but I could do nothing as the other man came back with a large club stick and was going to give it to me Mr Pedler was not come up then – I never saw them before and I had nothing to defend myself as I left my gun back on the Rocks when I first started after them … S. Weeks, Samford Courtney.” In a similar light a Gidleigh farmer reported that several of his sheep had been killed and butchered by miners travelling to the Steeperton Mine.

In 1877 the previous years lease belonging to Jeffery, Oldridge, and Langley was assigned to the Steeperton Mining Company. In 1878 the mine employed 27 men, 13 underground and 14 on the surface, and produced one ton of black tin valued at £34.40 which considering the enormous investment made is not that inspiring.

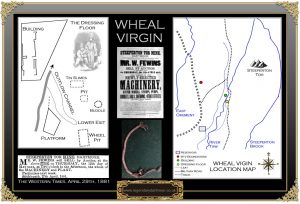

By 1879 an advertisement appeared in the Mining Journal that invited tenders for the purchase of the lease, machinery, and materials of the mine, it was headed the, “Steeperton Mining Company (Limited) in Liquidation.” The following year saw another advertisement for the auction of the plant, machinery, and effects of Steeperton Mine. In response to a letter from the Duchy asking why the workings were in such a dangerous condition, the owners replied that the company had been in liquidation since May 1879 and had been sold to a Mr Ficken.

The last known activity at the mine was on the 12th of May 1881 was the auction for the machinery, plant and equipment. A letter from Oldridge, dated June 1881 stated how the leats and wheel pit had been filled in and all the levels made secure. Yet another example of the old tradition that if you dare as much scratch the back of Dartmoor, Old Crockern will tear out your pockets.

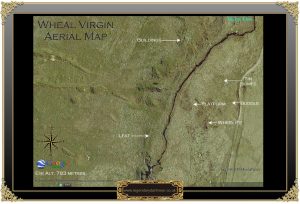

In 1995 D. Cranstone and I. Hedley assessed the site as part of the English Heritage Protection Programme for Industrial Monuments and below are the Ordnance Survey grid references for the major features of the mine. As can be seen above many of these are still visible on the aerial map.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6140 8840 – Remains of Wheal Virgin and remnants of of earlier opencast stream works and lode. possibly medieval or post-medieval.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6185 8789 – Openwork measuring 140 metres in length, 8 metres wide and 5 metres deep orientated north-west to south-east.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6132 8699 – Another openwork 65 metres in length, 30 metres wide and between 2 and 10 metres deep.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6128 8808 – A small openwork 70 metres long, 8 metres wide, and 4 metres in depth.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6125 8840 – Two linear openworks varying fro 70 to 80 metres in length, between 3 and 6 metres wide and up to 2.5 metres deep. Along with another ‘Y’ shaped openwork 100 metres long.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6141 8846 – A granite building 18.4 metres long, and 4.5 metres wide divided into two sections.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6143 8840 – The dressing floor which is 20 metres by 8 metres.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6144 8839 – A circular buddle with a diameter of 5.1 metres and 0.5 metres deep.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6142 8838 – A wheelpit measuring 9.9 metres by 3.0 metres

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6143 8842 – A level platform 8.8 metres in length, 6 metres wide and surrounded on three sidesb y a 0.4 metre tall bank. purpose unknown.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6140 8840 – A rhomboid raised platform, 16 metres long and 11 metres wide, possibly a base for timber sheds?

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6129 8836 – An adit

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6134 8841 – An adit

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6137 8840 – An adit

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6124 8840 – An adit

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6111 8792 – An adit, showing signs of being entered recently.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6126 8843 – Wheal Virgin boundstone, a granite triangular slab 1.6 metres tall, 1.9 metres wide at the base and 0,3 metres thick with the letters ‘WV’.

Ordnance Survey Grid Reference – SX 6096 8796 – A reservoir 80 metres long, 4 metres wide and standing 0.8 metres high this would have been the main water source for the mine. Fed by leats from a tributary of the River Taw.

Quite a few years ago three of us decided to explore the old mine in an attempt to find one of the adits described by Atkinson et. al. as being a, “collapsed adit portal.” It is usually possible to identify these by finding shallow reed filled gullies that run from the hillside and in this case such a feature existed just past the old ruined building. We found the mouth of the adit silted up with a trickle of water issuing out. After a few hours of digging it was just possible to squeeze through into the black abyss of the mine and it is quite possible that the comment above about the 5th adit being entered recently was down to us. I must admit the depth of water inside was a trifle alarming as it started off at chest height and was ice cold. As we progressed along the tunnel the water level dropped to about waist high but it was amazing the level of preservation of the timber supports. All in all the level ran about 200 – 300 water filled yards until it came to a dead end. Partway along the tunnel were some lumps of clay suck t the walls, these were where the miners would have lodged their candles. There was also a mysterious length of cord (see above) hanging from a small drill hole, it appeared to be a length of thick dark cord which had been bound by strand of much thinner twine. There were signs of burning at one end, as to its purpose I have no idea, detonating cord maybe?

The atmosphere in these old mines is amazing, usually a constant temperature, with complete silence that occasionally is broken by the sound of dripping water and if you turn your headlight of there is complete blackness. You have trouble literally seeing your hand in front of your face and it is only underground that you can experience this – I love it. Needless to say, nobody should ever enter any of the old Dartmoor Mines unless accompanied by experienced people and even then they still can be very dangerous places with gases, flooded shafts and unstable timbers. We have thus far been very lucky … and have retired?

Atkinson, M., Burt, R., & Waite, P. 1978 Dartmoor Mines, Univ. Exeter Press, Exeter.

Brewer, D. 2002 Dartmoor Boundary Markers, Halsgrove Publishing, Tiverton.

Burt, R. 1984 Devon & Somerset Mines, Univ. Exeter Press, Exeter.

Greeves, T. A. 1985 Steeperton Tor Tin Mine, The Devonshire Association, Vol. 117, Exeter.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor