There are numerous mires and bogs on Dartmoor, several of them can be treacherous places to wander into but of them all Fox Tor Mires is (undeservedly) the most notorious. It has been said that the mires are twenty feet deep and have sucked many a man and beast down into its peaty depths. The very mention of the place still strikes fear into the most hardened of ramblers who will avoid the quaking mass at all costs. Lying in a wide valley to the south of Princetown, Fox Tor Mires covers an area of roughly 1 square kilometre and is the birth-place of the river Swincombe. Dotted around the edge are reminders that man has trod the ground since prehistoric times and some have even been buried there.

Fox Tor Mires can present two very different faces, one is a landscape shrouded in thick impenetrable mists that hide the dark, peat stained pools of liquid peat. The other can be a quiet tranquil place where herds of ponies and cattle contentedly graze upon the lush vegetation. It is true that in wet weather prudence would dictate that the area id best avoided but in summer it can be a truly magical place. At one time the whole area would have been a bustling and noisy place with all the activities of the tin miners frantically prising the ore from the ground. Farmers lived and worked close to the mires and their old enclosures still stand as testament to their labours. In his book ‘The Miser’s Money’, Eden Phillpotts gives some very evocative descriptions of Foxtor Mire; ” “It was mid-June and Fox Tor Mire, brushed with quickening green, rolled out within its ambit of hills. New life of herbage smothered the grey s6re of the past, and in the valleys lush grasses beckoned the flocks and herds again. The mire was darkened by impermanent shadows from above and by the lasting stretches of heather that sprawled upon it, as yet untouched by blossom. From the bogs and reed-beds sparkled a cold, silver flash and fret of seeding cotton grasses. Peat cuttings yawned black in the fens, with scads piled to dry beside them, and cattle roamed even to the ridge of Cater’s Beam, where it swung glimmering vast along the skyline in a mantle of heat. Horned sheep with black faces and heavy fleeces panted and cried to be shorn ; the dun and black Scots cattle herded apart; upon the green downs stood many a mare in the sunshine, with a little foal stretched sleeping in the grass at her feet.” – p.364.

“This huge cup of jade exhibits scooped sides fretted with granite. Herein can a whole thunderstorm expend itself, or both foundations of a rainbow foot. Mists wander over its streamlets and break in waves of colourless light upon its sides; the Mire will often disappear under the grey sheets of a Dartmoor downpour; and in hard winters it lies beneath a pelt of snow, that reduces its immensity, dwarfs its details and makes Cater’s Beam look like a mighty polar bear. There is little high colour at any time. Sobriety characterises its tones, as restraint marks its contours. Even in August, when the lesser furzes glow and ling washes the waste with delicate rose and pearl, the dim green and grey persist among the far flung, gloomy passages of black and broken earth. Only at clear dawns and sunsets will Fox Tor Mire sound its highest colour song, brim with delicate and transient brightness, shine through all its granite reeves and clitters, and blush over its moss bogs, where the sphagna glow ivory white, emerald green and wine purple. Upon either brink of this great basin and separated by the miles of it flung between, there stand human dwellings.”– p1. The mires also make an appearance in another of Phillpotts’ books – ‘The American Prisoner’ as well as in Sabine Baring Gould’s book – ‘Gulvas the Tinner’.

The following account comes from the early 1900s when two gentlemen visitors left Princetown for a cross-moor walk to Ivybridge. The local advice was to simply take a compass and head due south until you come to Ivybridge, not long after leaving Princetown they met Foxtor Mires; “Then without warning we plunged into Fox Tor Mires. I say without warning, for the gradualness with which we became desperately involved in it was too insidious to be a warning. A little squelchy ground, a little more squelchy ground, some very squelchy ground, and then hey presto! we stood perched upon precarious tufts of grass, which barely gave foothold for both feet at once. The grass tufts were dotted at jumping distance from each other, and all between was soft, black, bottomless mire, beneath which lay the rotting bones of many a hapless visitor like ourselves.

In grim silence we leapt from point to point – always ‘due south,’ and testing every grass tuft with our sticks before we ventured to entrust it with our not-altogether-paltry lives. “Does it look and better further on?” inquired Seeby, somewhat pale. “Looks worse,” I said. I could see nothing further on but the jaws of death. “Well, I’m going to have some pasty before I die,” said Seeby. So we ate our pasties on our individual grass tufts, while the black ooze lapped about our soles, and the gorgeous wilderness of Dartmoor towered in its fantastic, awful grandeur beyond the loathsome sink of death into which we had been trapped.

The pasties were emphatically good, and we renewed our long-distance jumping with fresh heart. Whether it was a pleasant delusion for which the pasties were responsible, or whether the ground had actually improved, I do not know, but the situation became slowly better: and at length, with a heartfelt sigh of relief, we missed the squelch at our feet, and came outside of Fox Tor Mire.” – The Huddersfield daily Examiner, March 28th, 1907.

A similar tale was told back in 1874: “Fox Tor Mire was nothing less than one of the dreaded Dartmoor morasses, and we, in the midst of it, were likely to test the truth of the stories which we had hitherto treated as fables. With the recklessness of ignorance we decided that it was as well to go forward as turn back. That last leap across the wide peat ditch had been a stiff one, and neither cared to recross, for we found on attempting to probe it that our sticks sunk down as easily as if they had been thrust into water. So we hastened forward, leaping from tuft to tuft of rushes, and making as straight as possible for the highest ground, when suddenly we came upon the margin of a wide pool of black slush, in the middle of which could just be seen the skeleton back of a horse that had sunk and died there, leaving its flesh to the ravens and its bleached bones as a warning to all who might essay crossing the bog. We had heard strange tales of benighted travellers sinking suddenly into these treacherous morasses and being seen no more. Here was sufficient evidence of the possibility of a horrible fate which we confessed with an unpleasant shudder might still be ours. As we turned from the contemplation of this sickening suggestion our horror was not lessened when we saw a cold white mist sweeping over the hill and threatening to envelope us. There was just time to skirt the black pool and gain somewhat firmer ground before we were surrounded by a curtain denser and less penetrable by sight than a London fog.” – The Western Times, September 17th, 1874.

But as always it is the darker side which grabs people’s attention and lore and legend have certainly attached themselves to the mires. On the southern edge stands a lonely granite cross which marks the spot where Childe the Hunter perished on a cold winter’s night. Many folk have reported seeing the flickering flame of a Jack O Lantern which lures the unwary traveller into a deep, bottomless part of the mire. Tradition has it that this is the restless soul of a convict from Princetown Prison who floundered into the mires whilst making his escape only to be sucked to his death in the liquid peat. Not far from Childe’s Tomb lies an ancient tomb or kistvaen which dates back to the Bronze Age, this is known as ‘The Gold Box’ and was said to have contained treasure belonging to a long dead chieftain. Here also is a tale which has attached itself to various mire on Dartmoor, one of them being Fox Tor: A young man was traipsing home across the moor when he came to a livid green ‘feather bed’ and to his astonishment, there in the middle of it was a splendid top hat. Obviously some ‘gent’ had dropped it whilst trying to extricate himself from the mire. Never one to pass an open gate the lad delicately picked his way into the feather bed and picked up the hat. As he lifted it out of the quagmire his heart leapt into his mouth for there under the hat was a human head. The ‘stogged’ gent smiled and formally introduced himself in a posh city accent. The moorman immediately started to heave the man out of the bog but pull as he might he could not budge him. Again the gent smiled and explained that if the lad would wait a moment he would try to take his feet out of the stirrups of his horse that he was sat on.

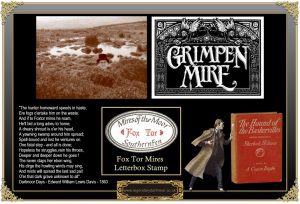

It was after a visit to the mires that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle got the inspiration for the Grimpen Mire which was the haunt for the infamous hound which was central to his plot in The Hound of the Baskervilles. Many Sherlock Holmes enthusiasts make the pilgrimage here to see for themselves the eerie Grimpen Mire, indeed some folk actually think of the place as the actual Grimpen Mire: “… over the great Grimpen Mire there hung a dense, white fog. It was drifting slowly in our direction and banked itself up like a wall on that side of us, low, but thick and well defined. The moon shone on it, and it looked like a great shimmering icefield, with the heads of distant tors and rocks borne upon it’s surface. Holmes’s face was turned towards it, and he muttered impatiently as he watched its sluggish drift… We left her standing upon the thin peninsula of firm, peaty soil which tapered out into the widespread bog. From the end of it a small wand planted here and there showed where the path zig-zagged from tuft to tuft of rushes among those green scummed pits and foul quagmires which barred the way to the stranger. Rank reeds and lush, slimy water-plants sent an odour of decay and a heavy miasmatic vapour into our faces, while a false step plunged us more thigh-deep into the dark, quivering mire, which shook for yards in soft undulations around our feet. Its tenacious grip plucked at our heels as we walked, and when we sank into it it was as if some malignant hand was tugging us down into those obscene depths, so grim and purposeful was the clutch in which it held us. Once only we saw a trace that someone had passed that perilous way before us,” – excerpts from The Hound of the Baskervilles, Arthur Conan Doyle.

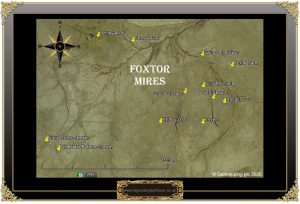

But what of the actual mire? As mentioned above, Fox Tor Mires lay surrounded by hills, Nun’s Cross Hill, Hand Hill, Crane Hill, Naker’s Hill, Steam Hill, Royal Hill and Peat Cott Hill. There are six main water courses which flow into its basin; Nun’s Cross Brook, Whealam Bottom Stream, T Gert Stream, Fox Tor Stream, the river Swincombe and the Strane all of which flow out of the mires united as the river Swincombe. The aerial photograph above gives some idea of the extent of Fox Tor Mires along with the remaining scars from tin mining and peat cutting. Mrs Bray simply notes the following: “… and the natives assured me that the golden plover bred in Fox Tor mire, which is a vast and dismal swamp on Dartmoor.“. John Lloyd Warden Page has even less to say on the matter, he simply states the fact that Fox Tor overlooks, “the famous or infamous, ‘Mire’“. Rowe and Crossing but just mention the name and Rowe does not even list it in his index. Luckily, Hemery has a little more to say on the matter and informs us of how at one time a path crossed the mire in a direct line from Drift Gate to Little Fox Tor. This old track followed the line of an overgrown reave and was also marked by a line of long gone wooden posts. He does warn that to lose the path along this track would be, “highly dangerous”. It has been suggested that when the Worth family were living at Peat Cott farm their route for crossing the mires was marked by scattered pieces of broken china along the track.

In 1912 a moorman named Willcocks was renting the Fox Tor newtake and in order to make it safer for his cattle to graze around the mire he dug a drainage gutter at the eastern end of the mire. This meant two things, firstly his animals could get to the lusher grasses on the edge of the mire and that the bank associated with the ditch provided another crossing place which became known as Willcocks’ Dyke’. Over time the ditch became clogged and in 1933 it had to be re-cut, since then there has been virtually no maintenance work done and all that remains are a few traces of the bank. Towards the eastern end of the mire are a series of small waterfalls that are known locally as ‘The Boiler’ below which is where a squatter named Sam Parr made his home in an old blowing house which became known as Sam Parr’s House.

Needless to say with many old place-name attached to features in and around the mire the area has become popular with letterboxers and at one time it was believed that there were well over 100 boxes hidden in the area. It was whilst looking for one of these that I met a spot of bother in the mire. It was during a warm September when the water table was low which meant it was possible to cross the mire towards the eastern end. I had been out around Fox Tor and rather than walk all the way around the mires I decided to cut directly across them. Suddenly I noticed a small figure lying in the middle of the narrow track which as I got closer rose up and began hissing madly. Now adders normally will slither off when encountering a huge, lumbering human but this one was obviously was having a bad day and he was going nowhere. So like the brave moorland hiker I am I went back around the mire and left it to sulk. Whilst on the subject of the local wildlife of the mire it was well known that at one time this was the place to shoot snipe, back in 1890 when such activities we legal on the moor one man shot 18 in a single day in and around the morass. Herons and foxes were also found there is much larger numbers than today.

Hopefully now, the notorious Fox Tor mires do not seem as bad they are made out but personally I would always recommend a stroll around the margins of its peaty interior, however, if you are brave enough a stroll through its peaty interior is always an interesting exercise. I would not say the same for Aune Head or Raybarrow Pool! Just remember the old Dartmoor adage – “where rushes grow ponies fear to go!”

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Hi Tim,

Such a wonderful article on Foxtor mires. However, I have been scratching my head as to where Willcocks’ Dyke might be. Do you know it’s exact whereabouts? I have an idea of one place it might be but after that I’m stumped. I shall look forward to hearing from you when you have a moment.

Kate Butterworth, Whiteworks