‘The frantic seer

Here built his sacred circle ; for he loved

To worship on the mountain’s breast sublime—

The earth his altar, and the bending heav’n

His canopy magnificent. The rocks

That crest the grove-crown’d hill he scooped to hold

The Lustral Waters ; and to wondering crowds

And ignorant, with guileful hand he rock’d

The yielding Logan…’.

N. T. Carrington – Dartmoor -1834

Easdon Down, one of the Dartmoor place-names that can easily lead one down the wrong path as to its etymology, ah yes, it derived from East Down as some early topographical writers assumed. Actually the earliest record of the place-name comes from the Lay Subsidy Rolls of 1330 when it was recorded as Yernesdon. The first element being ‘earn‘ as in the Anglo Saxon word for ‘eagle’, – Clark Hall, p.96, and the second being ‘dun‘ meaning hill, – Clark Hall, p.90, thus giving ‘Eagle’s Hill’. – Gover et al.,p.482. The ‘down’ was added giving ‘the down of the eagle’s hill’ and no more an apt a name could be found. When you look up at its huge dome it’s not hard to imagine this as the one-time haunt of eagles who from the lofty granite heights surveyed all before. The huge prominence appears to be an island in a sea of irregular patterns of prehistoric fields which lap all around its base. Today there is a line of thirteen boundstones which neatly hives off the bottom third of the down and denotes the dividing line between the parishes of North Bovey and Manaton. This line is by no means the earliest land division on Easdon as some of the boundary stones stand on a prehistoric reave, in fact several of these reave systems seem to converge around its lower slopes. Fleming, p.66 notes how: ‘Easdon Hill itself is a marvellous place to visit; it is a meeting-place for three or possibly reave systems, which converge upon it first as ‘fossilised’ modern hedges, and then on the heath clad summit, as reaves, some of which were reused as boundaries in the Middle Ages.’ It is interesting how three distinct areas to the North, South and East of Easdon Tor have not been incorporated into the parallel reaves, it is as if it was purposefully set aside to act as a kind of ‘no man’s land’. On the top of the hill sits a cairn which clearly shows signs that at some point in time it has been rifled, possibly by people looking for supposed buried treasure – namely the infamous Dartmoor Tomb Raiders. There is a large, square slab lying in the centre of the cairn which may well be the capstone from a burial kistvaen. Aside from the reave systems there are also some scattered hut circles on the down which in general fall into two groups of four huts. The only remarkable thing with these huts when compared to others on the moor is their sizes with several of them having diameters of over 7 metres. This may well suggest that the Bronze Age population of the down was about 12 adults plus any children. This estimation is based on Butler’s theory of any hut with an internal diameter of over 7 metres would house 4 adults. (1997, pp.140 – 1). However, it may well be that many other huts circles have been lost lower down the down when the later farmsteads and enclosures were established, in which case the population numbers would have been much higher.

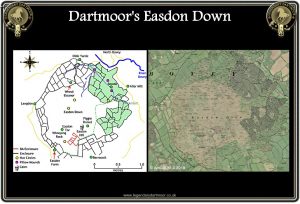

As can be seen from the map below the scattered farmstead and network of small irregular fields around the down display admirably a typical example of an ancient fieldscape. Today Easdon Down is registered as common land (CL 147) under the Commons Registration Act 1965. Rights of common of pasture, estovers, turbary, and common in soil are also registered in respect of the land. Not only is and was Easdon Down used for agricultural purposes because on the very northern edge is the site of an old mine known as Great Wheal Eleanor. The 1889 map opposite clearly shows the mine, its workings and shaft, in fact the Great Wheal Eleanor Mining Company was formed in 1874 with the express intention or re-working an earlier tin mine. It has been suggested that the first tin extraction began sometime between the 15th and 17th centuries and was based on an openwork mining operation. In 1876 3 tons of black tin was extracted and this fetched the princely sum of £129, an inspection the following year reported that a lode situated 20 fathoms down in the Engine Shaft contained an estimated 33lb of black tin to the ton, (Hamilton Jenkin, 1974, p.108). By 1878 the output from the mine had had risen to 10.8 tons at a value of £326.10, in 1880 it was estimated that the lode found in the deeper New Shaft was capable of yielding 70 – 80 lb of tin to the ton. The mine being situated just over a kilometre from the village of North Bovey provided an important source of employment and prosperity for the village, by 1880 there was a total of 15 people employed at the mine. However Great Wheal Eleanor was a short lived venture as in 1881 the output had dropped to 5 tons with a further drop to 2 tons the following year. By 1884 the mine was abandoned and all the buildings etc were deserted, for further information on the mine, it’s building and equipment follow the Pastscape link – HERE. In addition to farming and mining taking place on the down but very possibly rabbit warrening, there are several supposed pillow mounds recorded near to Bowda which although today is lost in a plantation of trees was shown as open land on the 1899 map. Sadly there is no conclusive evidence for a rabbit warren, just the vague entries for the mounds.

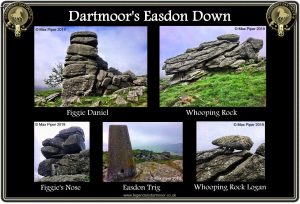

There are several rock plies scattered across the down but probably the most noted is Easdon Tor itself from which on a fine day extensive views can be admired on the 439 metre elevation. For those interested in Ordnance Survey trig points number S3542 can be found on the tor. Another ‘jewel’ in the crown of Easdon Down is the strangely suggestive Whooping Rock which is located just above Easdon Tor. At one time this would have been what is known as a Logan Stone but as can be seen from below it hasn’t ‘logged’ for several hundred years: “On East-down, in the parish of Manaton, is a Logan-stone, called in the neighbourhood the Whooping Rock, from the noise which it used to make, when set in motion by the winds. In stormy weather, it might be heard at the distance of at least three miles, with the wind. A few years ago, several persons moved it by main force, off its balance. So that it loggs no more. It is evidently a druidical Logan-stone – and has been venerated by the superstitious neighbourhood as an enchanted rock, from the times of the Druids to the present day: And the hands that wantonly displaced it from its primitive position, are execrated by the villagers around, as having profanely violated the spirit of the rock. Two ledges of stone run parallel to each other, with a considerable opening between them; or rather one large rock, disparted by some violent convulsion. A stone was placed at the west end of the south ledge, on one little point. This, then, was the Logan-stone, that moved at the slightest touch, whilst it preserved its equipoise.” – Polwhele, p.57. The early chroniclers well acquainted with the Druidical theories suggested that Whooping Rock was deemed to be somehow a special ‘enchanted rock’.

It is worth bearing in mind that many of the early Dartmoor antiquarians held the belief that logan stones were used by the Druids in some of their rites and rituals hence both Polwhele’s mention and that from Carrington’s poem at the top of the page. Crossing puts forward another explanation of the name when he notes that there was once a local tradition whereby children suffering from whooping cough were taken to the rock in order to be near the sheep that frequented the area. – p.264. It was believed that by being left for a time near the sheep would in fact cure whooping cough, in a way one can see the idea, just sit for a while amongst sheep and smell the ammonia from their urine and see what happens, However, Hemery, – p.724, offers another equally illusive suggestion by saying that in the locality the granite pile was always known as ‘Piggie Rock’ but sadly he offers no explanation. It could be however that the name ‘piggie’ is now a corruption of what once was ‘puggie’ thus indication some connection to the piskies?

On the eastern edge of the summit of Easdon is another rock pile that also has a very intriguing name – Figgie Daniel. Of this I can discover nothing further apart from a very brief and uninformative mention of the name by Hemery who says; “The easterly extremity of the down, known as Easdon Hill, is marked by a cairn and the conspicuous rock-pile of Figgie Daniel…” – p.724. In answer to this question the Hemery tradition carries on – Emma Cunis, Eric Hemery’s granddaughter has now provided a plausible answer by saying; “Figgie Daniel (or ‘Big Nose’) is allegedly named after a local shepherd Mr Henry Daniels who lived at Ford Farm in Sticklepath…. The main features of the Daniels men were that they were tall, have large noses, jaws, chins, large hands and a dark complexion. Figgie certainly displays these features.”

So there you have it, Easdon Down, eagles, a prehistoric no-man’s land, a tin mine, rabbit warren, druids, a defunct logan stone, a cure for whooping cough, piskies and someone called Figgie Daniel who had a large, hooked nose -what more could anyone want?

According to M. S. Gibbons on the Good Friday of 1885 a young lad was walking alone across the down and for whatever reason stopped to cut a branch of furze. Somehow his pocket-knife slipped and entered the calf of his leg. He managed to staggered a few steps and fell to the ground in agony. A passerby happened to hear his groans and went to his assistance but sadly a short while afterwards the boy bled to death before medical assistance could be reached. – The Exeter & Plymouth Gazette, June 23rd, 1886.

My thanks to Max Piper for kindly allowing me to use his photographs of Easdon Down

Butler, J. 1997 Dartmoor Atlas of Antiquities – Vol. V, Devon Books, Exeter.

Clark Hall, J. R. 2004. A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, London: University of Toronto.

Crossing, W. 1990. Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor, Newton Abbot: Peninsula Press.

Gover, J, Mawer, A. & Stenton, F. M. 1992. The Place Names of Devon. Nottingham: English Place-Name Society.

Hamilton Jenkin, A. K. 1974. Mines of Devon – Vol. I., Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

Northern Mine Research Society. 1993. Devon & Somerset Mines, Exeter: Exeter University Press.

Polwhele, R. 1793. Historical views of Devonshire: Vol. I, London: Cadell, Dilly, and Murray.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

I enjoyed reading the history of Easdon Downs.