A long time ago came a man on a track

Walking thirty miles with a pack on his back

And he put down his load where he thought it was the best

Made a home in the wilderness

He built a cabin and a winter store

And he ploughed up the ground by the cold lake shore

And the other travellers came riding down the track

And they never went further, no, they never went back

Then came the churches then came the schools

Then came the lawyers then came the rules

Then came the trains and the trucks with their loads

Dire Straits 1992 – Telegraph Road

In 1785 Thomas Tyrwhitt arrived on Dartmoor, at the age of 23 he had leased a tract of moor comprising of over 2,000 acres with the view to ‘taming’ the land and establishing a large agricultural estate. By all accounts the estate which he called Tor Royal was completed by 1798 and comprised of his house, gardens, fields and plantations. The foundation of any such venture naturally involved the employment of a large workforce, some of whom would need accommodation. In this light a small inn was built which was called The Plume of Feathers and to this day it still provides lodgings, food and ale.

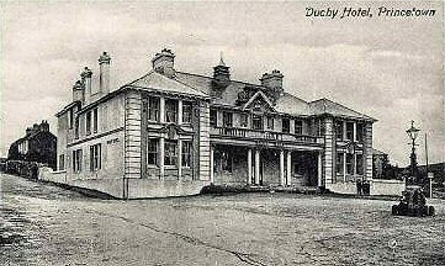

As with most schemes which involve ‘taming’ the moor, Tyrwhitt’s grand plan failed, however he was not the sort of man to let such a minor setback stand in his way and so in 1806 the foundation stone of Dartmoor Prison was laid. This whole purpose of this building was to house the hundreds of prisoners taken during the Napoleonic War. With so many prisoners to guard it is not surprising that along with the gaol came numerous service buildings such as bakeries and a slaughter house. In addition the guards needed barracks and their officers’ quarters, both of which were duely erected. It is at this period of time what was later to become the Duchy Hotel was constructed as the officers’ quarters. William Crossing, (1989, p.24) explains how: ‘This hotel was originally built for officers’ quarters… It dates, however, from the early days of the prison‘. Along with the quarters came a brewery which later formed the kitchens of the hotel, Crossing mentions that during his time a large copper vat belonging to said brewery was still to be seen in the yard of the hotel. However, I am jumping the gun somewhat.

The first prisoners began arriving in 1809 and before long the hamlet of Princetown grew into what has been described as a small town with new houses and a church being built. In 1813 the number of prisoners increased with the arrival of 250 men who had been captured during the American War which again meant a growth in the size of Princetown. However, wars cannot last forever and by 1816 many of the prisoners had been repatriated which resulted in a redundant prison and a rapidly declining Princetown.

It is at this point that tradition maintains the Duchy Hotel came into being, sometime in the early 1850s a local man named James Rowe converted the old officer’s quarters into a hotel, (Gardener-Thorpe, 203, p.15). This date is also confirmed by James, (2002, p.6) when he notes: ‘The prison stood empty until 1850 when it opened again, this time as a convict prison. Shortly afterwards the officers’ accommodation was acquired by Mr James Rowe who refurbished it before opening the Duchy Hotel.’ However, there is one slightly confusing factor here, in a newspaper notice which appeared in the Exeter Flying Post dated the 19th of November 1812 there is mention of an auction to be held at the Duchy Hotel in Prince Town – see below:

This to me would indicate that in 1812 there was a building known as the Duchy Hotel in Princetown which if this is the same building slightly contradicts the accepted date of 1850 by a good few 48 years? Three years later on the 21st of September 1815 another notice appeared in the same paper that a General Court Baron for the manor of Lydford and the Forest of Dartmoor was to be held at the Duchy Hotel – see below:

Things get more confusing, but the fact that the Court Barons were held at the Duchy Hotel is confirmed by Evans (1846, p.174) when she states: ‘After Prince-town was begun on the moor, Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt, who had much influence with George the Forth, then Price of Wales, succeeded in getting him to order the courts to be held at the Duchy Hotel, on Dartmoor, where they continue to be holden to this day‘.

Then in 1826 another notice appears in the Exeter Flying Post which announces the auction of an inn called The Duchy Hotel at Prince Town. As can be seen below the lot comprised of the hotel, stables, coach house, cottages, outhouses and stable yard all of which belonged to a Mr. Worth. The inn is described as being, ‘very capacious, and calculated for a large and respectable business‘. Crossing, (1989, p.34) states how the baptismal register for Princetown mentions a John Ellis and an Edward Worth as both keeping inns there in 1816. However, as he notes: ‘There is nothing to show whether this points to one or two inns, but there were at that time two in the village, the Plume of Feathers and the one afterwards called the Railway Inn .’

This time there is a name for the tenant although sadly no description as to where the Duchy Hotel was located. Clearly it was used as a coaching inn hence the presence of stables, coach house and stable yard, this in turn would suggest passengers and guests in need of a hotel. Could it just be that at one time the Railway Inn was called the Duchy Hotel which was then later transferred over to the old officers quarters? After all, the railway did not appear in Princetown until 1883 so why should an inn be called after something that did not exist. A possible indicator to this could be inferred from Crossing’s comments when he says: ‘and the one afterwards called the Railway Inn’? I am sure the answers will lie somewhere in the records of the Duchy of Cornwall and I wish I had the time to seek them out.

Either way. it appears that at around 1850 James Rowe now owned the nearby Railway Inn as well as being the local blacksmith, storekeeper and dentist, (Crossing, 1989, p.36). It appears that in the early days of the Duchy Hotel James Rowe, although clearly a talented man, lacked the skills necessary for a hotelier as the description below indicates.

Prince’s Town (a poor inn called the Duchy Hotel) lies on the Plymouth road, about 2 m. from Two Bridges, and is one of the most gaunt and dreary places imaginable. It is situated at least 1400 ft. above the level of the sea, at the foot of N. Hessary Tor… With such dismal scenery the hotel is in keeping; its granite walls are grim and cheerless, but the windows command an imposing sweep of the waste, and this will be the attraction to many travellers.’, (Paris, 1851, p.79).

It is interesting to see that in the 1863 edition of A Handbook for Travellers in Devon and Cornwall the author had slightly amended his description to, ‘a tolerable inn called the Duchy Hotel‘. But, although ‘poor’ may have improved to ‘tolerable’ it seems that by 1860 the establishment still left a lot to be desired as can be seen by one residents experience:

‘On entering the inn, which boasts of the high-sounding title of the Duchy Hotel, we expressed some regret as not having continued our walk so far on the previous night; but practical demonstration soon convinced us that while we should have lost the highly interesting sights of “Crockern Tor” and Wistman’s Wood, we should only have exchanged outward grandeur of appearance, dirt, and extortion, for humble cleanliness, moderation, and civility… As regards ourselves, we had been hard at work on foot all the morning, by no means a bright one; therefore, previous to entering the prison, we called on the landlady, who appeared to combine master and mistress in her bony person, for refreshment, under the denomination of luncheon, which being produced, consisted of some stale bread, bad cheese, and worse beer. This, as may be supposed, we scarcely touched; the charge was, nevertheless, exorbitant. Being the keeper of the general purse I ventured to remonstrate with the good woman, stating that we had breakfasted amply for half the sum. “Maybe,” she replied, somewhat rudely; “I always charges the same for breakfast and luncheon.” Be it so. In future I shall order breakfast when chance leads me to the Duchy Hotel; fresh eggs are at all times preferable to stale cheese. Moreover, I am of the opinion, while civility, cleanliness, and fair charges should always be held up as examples, dirt and indifference, if not rudeness and extortion, always should be censured when evinced by those who cater for the public.’, (The Ladies’ Companion, 1860, p.137).

Although James Rowe would probably not have been given an RAC recommendation had it existed then he certainly either had a good eye for an opportunity or was very lucky. Having suffered a good few years in decline Princetown was about to see its fortunes improve. In 1850 the prison was re-opened to become a convict prison and in 1883 the railway connecting Princetown to Plymouth was opened. Also around this time people in search of the ‘picturesque’ started to come to Dartmoor and Princetown made an ideal base from which to go exploring. All of these factors meant that Princetown once again became a busy place with people needing a place to stay. By the early 1900s the hotel had passed down the Rowe family and came under the ownership of James’ grandson Aaron. In 1908 he began a scheme of renovation which was completed in 1909 and on June the 10th of that year was visited by the Prince and Princess of Wales. The actual design was the work of a Plymouth architect called F. A. Wiblin and many of his features can be seen today. Probably the most noted is the mosaic floor, part of which stands in the main hall of the building – see below:

This was to be the first of many royal visits to the Duchy Hotel over the years and the place soon became the centre for any royal excursions on the moor. In 1914 the building was again altered by the addition of an extension that was designed by architectural firm of Richardson and Gill. Further changes were made to the building in 1928 when the ground floor rooms were converted into a dining room. In the early 1900s it is interesting to see how the adverts for the hotel changed and what features they used to attract guests. Below are are few examples taken from the Times Newspaper:

As can be seen, in 1914 Aaron Rowe was using the fact that the establishment was ‘patronised by Royalty’ as a crowd puller and such facilities as heating throughout, electric lights and British staff (seems like nothing has changed?). I particularly like the contact phone number – 2. A few years after this advert Aaron Rowe died in 1919 and the Duchy hotel passed onto his son George and as can be seen the adverts began to feature a family hotel with modest rates that gave easy access to, ‘the finest fresh air in the country‘ along with excellent opportunities for the angler. Later the opportunities to visit the nearby antiquities were extolled along with, ‘beautiful moorland walks and drives‘. According to the Ward Lock guide to Dartmoor it was possible in 1927 to stay at the Duchy Hotel in a double room with breakfast, luncheon, tea and dinner for 18s and 6d a night. Based on today’s average earnings this would equate out to £169 which easily places the hotel into the four/five star category for tariff if nothing else.

Clearly the advertising worked as over the years the hotel attracted many famous authors, painters and members of parliament. Prince Albert was entertained at the hotel in 1852 after visiting the prison. Winston Churchill also took lunch there after he too visited the prison. Lord Tennyson is amongst the hotel celebrity list as too is Conan Doyle was reputed to have stayed at the hotel whilst writing several chapters of his novel – The Hound of the Baskervilles. William Crossing was a regular patron of the Duchy Hotel where he became great friends with Aaron Rowe who in later years wrote the forward to his book – Amid Devonia’s Alps. Amongst the artists who stayed there were B. W. Leader who was supposed to have painted some ‘exquisite gems’ on the shutters of the hotel. Although William Crossing refutes this by saying Aaron Rowe informed him that a Mr. A. B. Collier was the culprit, (Crossing, 1966, p.125).

Despite the patronage of the ‘great and good’ the hotel’s fortunes began to fall until eventually the building was taken over by the prison service in 1941 to be used as an officers mess. The building became known as Duchy House and in addition to being used as a mess the building also served as quarters for bachelor wardens, (James, 2002, p.7). In 1991 the building was completely refurbished jointly by the Duchy of Cornwall and the Dartmoor National Park Authority. This work was completed and on the 9th of June 1993 H.R.H. Prince Charles officially opened the new High Moorland Visitor Centre. The building now serves as offices for the DNPA the Duchy of Cornwall, the Dartmoor Area Tourism Initiative and the Dartmoor Preservation Society as well as serving as a visitor’s centre.

Over the years the hotel had served as a meeting place for many societies and clubs. In the August of 1856 the 901 Masonic lodge of Princetown was opened by the Grandmaster, this occasion was marked with a procession which lead from the Duchy Hotel to the church and was followed by a banquet back at the hotel. During ‘Dartmoor Week’ the hotel became the headquarters of the Dartmoor Hunts as they gathered for a week of hunting.

There have also been some tragic or strange occurrences at or near the hotel. In the February 1853 a tragic event occurred during a heavy snowstorm when a soldier travelling to the prison collapsed and died, his body was found on the 17th of that month 200 yards from the Duchy Hotel. In 1896 there was a strange and protracted legal case centred around the Duchy Hotel and involved a breach of promise where one slightly deranged Mr Creed was charged with promising to marry one Miss Seeley.

So from an officers’ quarters to hotel back to quarters for prison warders and then to a visitors centre the Duchy Hotel could tell some stories. In fact today it literally does tell a story – that of Dartmoor. Ironically the story, like the displays does not change much but if ever you are in Princetown and its raining the you can pass a few minutes in the dry by looking at the various displays and exhibition. It’s probably more rewarding to search out the various architectural features of the old hotel and imagine the building at the height of its opulence.

Reference.

Crossing, W. 1989. Princetown – Its Rise and Progress. Brixham: Quay Publications.

Crossing, W. 1966. Crossing’s Dartmoor Worker. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

Evans, R. 1846. Home Scenes, Or, Tavistock and Its Vicinity. London: Evans and Marshall.

Gardner-Thorpe, C. 2003. The Book of Princetown, Tiverton: Halsgrove Publishing.

James, T. 2002. About Princetown. Chudleigh: Orchard Publications.

The Ladies Companion, 1860. Dartmoor and its Prison. London: Rogerson and Tuxford.

Paris, T. C. 1851 A Handbook for Travellers in Devon and Cornwall. London: John Murray.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

My grandmother and great grand mother were the managers of the hotel during 1926 mutiny at Dartmoor prison and in her memoirs she explains the Duchy’s role in proceedings and the judges and police superintendents that came to stay, as well as the night of the mutiny and she talks of all the reporters from around the world that camped out in the hotel.

I was born in the Duchy Hotel on the 12th June 1941 as my father was a serving Prison Officer. I have returned many times staying at the Cherrybrook Hotel wic h at one time was owned by family friends. As a young boy I remember delivering milk in Princetown with my elder brother, I have happy memories of Princetown.

My grandfather was a waiter at the Duchy Hotel and died there in 1897, witnessed by his wife. My father was just 6 months old.