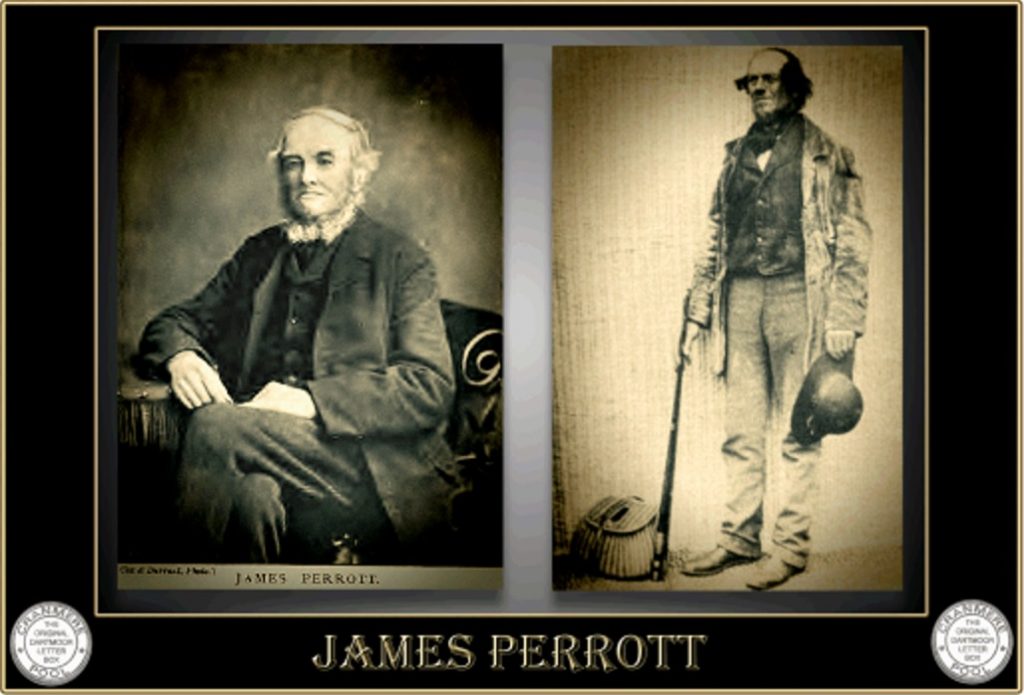

“James Perrott, the well known guide, the best living authority on that land of tors, of which he is, indeed, a veritable ‘walking cyclopaedia.” – J. Ll. W. Page 1895.

Back in the time when there was no such thing as health and safety, personal injury claims and perceived danger around every corner anyone wishing to venture out into the wild lands of Dartmoor simply hired a local guide. Very often these would be moormen who had spent their lives living and working on the moors and knew every stream, tor and mire. During the 1800s there was no shortage of wealthy people in search of the picturesque, writers seeking inspiration, antiquarians seeking out the Druids or simply anglers wanting to fish the streams of Dartmoor. It was to this kind of clientele that James Perrott offered his services and expertise.

In 1812 John Stanford Perrott married Agnes Gay following which they moved to Thorn Farm which is located just outside Throwleigh. It is said that the Perrott family (on the maternal side) could trace their ancestors back to the times of the Normans coming to Britain. The family motto was/is – “AMO UT INVENIO.” or roughly translated – ‘I Love as I Find’. In later years proof of this lineage hung in the Perrott’s shop as one visitor noted; “… our eye fell upon a framed parchment from the Garter King of Arms relative to the bearing of arms by an ancestor of the Perrotts.”, Gibbons, p.46.

In 1813 Agnes gave birth to their first son; Albert, then in the March of 1815 James Perrott was born. It was he who in later years would become ‘The Dartmoor Guide’ and whose reputation would dwell in the realms of Dartmoor legend. Initially James began his working life as a wheelwright but then diversified into making and selling fishing tackle from a small shop in Chagford Square. Perrott’s shop can be found in the 1870 edition of Morris and Co.’s Commercial Directory and Gazetteer where the following listing appears: “Perrott, James. fishing tackle manufacturer, and guide to Dartmoor Forest, The Square.” Gradually Perrott’s business empire expanded and added to his guiding services was the hiring of saddle horses/ponies and carriages. In his later years it is at this small shop in Chagford Square where in his final years he spent most of his time.

In 1839 James married a local farmer’s daughter – Mary Harvey which proved to be a very ‘productive’ relationship which gave them four sons; Richard, Stanford, William and James along with four daughters; Elizabeth, Emma, Louisa and Ellen., Stanbrook, p.16.

Over time ‘Old Perrott’ (as he became known) amassed an extensive knowledge of Dartmoor that led to an illustrious guiding career and as Crossing noted: “We have heard him spoken of three thousand miles from Dartmoor, and the memories his name recalled, it was evident to us, were among those most cherished.”, p.57.

Amongst the rich and famous that availed themselves of his services were the authors Charles Dickens, Charles Kingsley and R. D. Blackmore. One can assume that ‘Old Perrot’ had a profound influence on Blackmore as he was characterised in his Dartmoor novel – ‘Christowell’. The antiquarian, Samuel Rowe supposedly engaged his assistance when researching his book, ‘A Perambulation of Dartmoor which was published in 1848.

Writing in 1890s, J. Ll. W. Page tells how Perrott, then in his 80s and described as; “hard as nails“, could be found in his small shop at Chagford. It was here that he would: “discourse on matters pedestrian and piscatorial; he knows Dartmoor from Tavy Cleave to Gidleigh Common, from Princetown to Okehampton Park, and every likely ‘stickle’ in the Teign from Siddaford Tor to Clifford Bridge.”, p.73. In other words there were very few parts of the Northern part of Dartmoor that Perrott was not conversant with.

There is a local tale related by Brooking Rowe that on one of his moor excursions he crossed paths with the infamous Black Dog of Dartmoor, not only did he encounter it, apparently in true Grizzly Adams fashion – he wrestled with it, p. 421. – no wonder Page described him as, “hard as nails.” However, there is another version published in the Western Morning News which attributes the encounter with the Black Dog to James’ father John. In this one the beast was encountered swimming in some water and fearlessly John set about it with his riding crop, Stanbrook, p.16.

In 1887 Murray’s ‘Handbook for Travellers in Devonshire’ noted the following; “Light carriages are to be hired at Perrott’s in the principle street, and chaises at the inns. Perrott himself is well known as the “Dartmoor Guide:” and under his care or that of his sons (who are not less competent) the stranger who shrinks from solitary adventure may explore in safety the wildest recesses of the moor.”, p.131.

As indicated by the above, Perrott’s sons had also taken on the role of Dartmoor guides, certainly by 1886 as testified by M.. S. Gibbons. She wrote a description of one such guided excursion conducted by one of the sons in which she recalled:

“We made our way to Mr Perrott’s, and again lost our opportunity of being introduced to Mr. Perrott senior, who was out, as also was the son who drove us on Friday; but there is a good supply of ‘Perrotts Jun.,” and another son came to our assistance whom we found quite worthy of the name… We were greatly struck with the skill of our to-day’s driver. Our roads were as about as bad as anyone could imagine; and Mr. Perrott had by a painful accident disabled – we trust for a very short time – his left hand. Not only did he accomplish the unusual feat if driving over the roughest ground with his right hand, but quietly held the reins with knees when his right hand needed to apply the brake.”, p.46.

This particular excursion went from Chagford to Holy Street, on to Throwleigh then to Gidleigh Castle, from there the route went to Scorhill Circle and down to The Tolmen Stone in the river Teign. The final leg went back to Kes Tor, past the Round Pound and finally finished up at Beetor Cross.

Incidentally, the other nameless son who drove the Gibbons’ party on the Friday as mentioned above was according to her equally as “worthy of the name.” On this occasion their excursion went from Chagford to the top of Hunters Tor above the Teign Gorge which was no mean feat and one which she; “never believed mortal pony could attain.” From there they proceeded to Drewsteignton church and then dropping down to Fingle Bridge, next came nearby Cranbrook Castle with a final stop at Moretonhampstead where they, “bade their kindly and interesting driver farewell.”, pp.38 – 41.

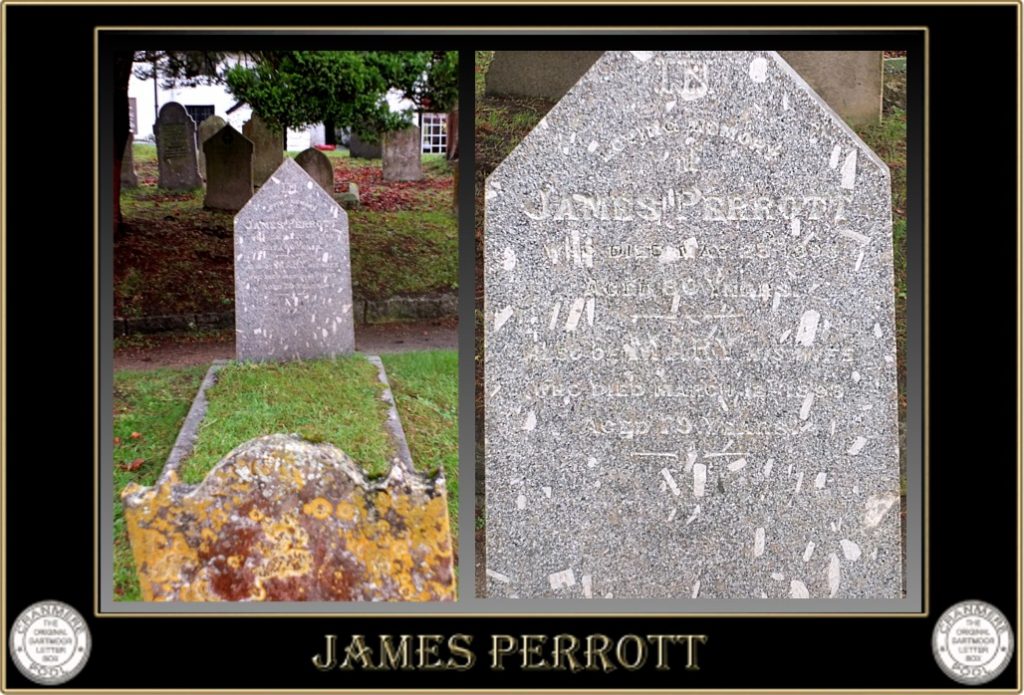

James Perrott passed away at the grand old age of 81 and was laid to rest in the churchyard at Chagford In 1895 an obituary appeared in a publication called – Bailey’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes written by the author F. B Doveton the who had clearly spent much time with Perrott, gave his impression of the man along with several memories of time spent with him. These very moving and informative words can be read – HERE.

I think it fair to say that if most people were asked; “what was James Perrott’s claim to fame.”? The answer would be that he was the man who unknowingly started the Letterboxing phenomena on Dartmoor. Certainly if you put his name into Google most of the top hits will be referring to Letterboxing and Cranmere Pool. Probably one of the remotest spots to which Perrott would guide people was Cranmere Pool. Clearly his clientele wanted some kind of memento of their expedition, a kind of ‘I woz here‘ statement of the achievement. So in about 1854 Perrott installed a glass jar (some will say it was a pickle jar) on a small stone cairn which he built at the pool. The initial idea was that visitors could leave a calling card in the jar as proof they had been there.

In the 1867 Perrott guided one Horace Waddington along with some friends to Cranmere who wrote about the journey which started at 10.00am at Chagford where a “trifling sum was paid,” to ‘Old Perrott’.

“There it be, sir,” says Perrott, suddenly: and there, indeed, it was – the famed Cranmere, the Lake of Cranes, a dried-up hollow in the black bog, some two hundred yards round, with a miniature cairn of stones on its edge, to which we walked dry-shod through what should have been the Pool. This little cairn our guide had dubbed his post office; here for no less than twelve years, he had kept among the stones a bottle, into which visitors to the spot were requested to drop their cards, and he enumerated, with some pride, a bishop, a lord, and several artists, whom he had guided thither. But not even in this seclusion had the poor bottle been safe – it had actually been stolen!“, p.281.

After reaching Cranmere pool they made their way to Lydford Station where the train was boarded for Mary Tavy. Here ‘Old Perrott’ got off and made his way back across the moor to Princetown and then home to Chagford. Which if correct, and he walked it then he trudged about another twenty miles or so?

“What goes around comes around.”, – fairly recently the closure of the military road up to OP15 (from which was the easiest and shortest way to reach Cranmere Pool) has now meant that the best way to get there is (excluding the Gidleigh Park bits) ‘Old Perrott’s’ route as described above.

At some unknown date between 1889 and 1903 the glass jar was replaced with a tin box and an official visitors book which would have been after Perrot had died. This ritual of recording visits to remote locations led to the popular pastime of today’s letterboxing which now has spread worldwide. In a nutshell, the idea is to hide a stamp and visitors book and then provide clues as to where it can be found, more of which is explained on the ‘Letterboxing’ link above. Since the advent of GPS receivers letterboxing acquired a ‘little brother’ in the form of Geocaching, which again is where folks look for hidden caches. I often wonder what ‘Old Perrot’ would say if he knew exactly what his little glass jar of calling cards would evolve into?

In lax moments I often ponder that if given the chance which of the past Dartmoor notaries I would like to have dinner with. Simple – William Crossing, Eric Hemery and James Perrott. Imagine what pearls of wisdom that conversation would harvest.

Brooking Rowe, J. 1985. A Perambulation of Dartmoor. Exeter: Devon Books.

Crossing, W. 1987. A Hundred Years on Dartmoor. Exeter: Devon Books.

Doveton, F. B. 1895. Bailey’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes – Vol.64. London: Vinton and Co. Ltd.

Gibbons, M. S. 1886. We Donkeys on Dartmoor. Exeter: Henry S. Eland.

Murray, J. 1887. A Handbook For Travellers in Devonshire. London: J. Murray.

Page, J. Ll. W. 1893. The Rivers of Devon from Source to Sea. London: Seeley and Co., Ltd.

Stanbrook, E. 1995. James Perrot of Chagford – The Dartmoor Magazine – No.38. Brixham; Quay Publications.

Waddington, H. 1867. Straight Across Dartmoor – Temple Bar -Vol. XIX, London: Richard Bentley.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Thank you Sir.

Chagford Square is a long way from Toronto so I first experienced part of Dartmoor three years ago, with an excellent Guide.

This is wonderful in helping me learn more about my great great grandfather.

I can confirm there have been two “t”s for a long time.

Good article but a good point David, I wonder if the connection with the armigerous family was real or just hoped for!

Hi again David,

When you visited Chagford did you happen to see the Perrott Coat of arms owned by the ancestors of James Perrott?

I have a photo of myself holding one taken many years ago and wondered if it was the same one.

Hi Anne

Sorry, only just noticed your comments.

I visited Dartmoor, Gidleigh and Chagford again in October 2017 and was thrilled to meet wonderful folks from Dartmoor Magazine and The Moorlander.

My father has a copy of (very detailed) Perrott Coat of Arms, A Comprehensive Pedigree and related documents from Belbroughton – developed in part from The Midlands Antiquary; however I suspect the Coat of Arms may differ from the “Garter” version described in Tim Sandles terrific article, and that you were photographed with. Naturally I would be most pleased to see the photograph.