Dean Prior is a tiny hamlet that literally hugs the boundary of the Dartmoor National Park so closely that it cruelly separates its church from its flock. Today many people associate Dean Prior as being the one-time home of the prolific Dartmoor poet Robert Herrick but there was also one other famous person who made their home at Dean Prior – James Thorpe. In 1933 he published a book called “Happy Days” which in his own words were his “recollections of an unrepentant Victorian.”

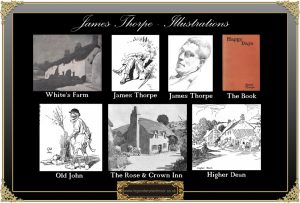

James Thorpe was born in Homerton, London on the 13th of March 1876, He was the seventh of nine children sadly only three lived beyond childhood. At an early age he was sent to a small kindergarten near to the family home and later moved on to a London Board School. From there he managed to obtain entrance to Bancroft’s School where he described life as; “almost monastic in its simplicity and seclusion.” It was there that he first gained a passion for cricket which was to stay with him all his life, he also developed an interest in cartoons and often contributed to the school magazine. On leaving school he began taking lessons from Alec Gould who was the son of Francis Gould a famous cartoonist whose work appeared in the Westminster Gazette. Thorpe then managed to gain entry to the Lambeth School of Art and then transferred to the North London School of Art. Over time his career progressed and he became a member of the London Sketch Club and the Chelsea Arts Club. In addition to his black and white sketches and cartoons some of his other works were exhibited with the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour and at the Leicester Galleries, London. It did not take long for his talent to become recognised and his sketches and cartoons began appearing in various publications culminating his works being often published in the Punch Magazine from 1909 to 1938. It was not just magazines and newspapers that were displaying his talents and thanks to his passion for cricket and also angling they appeared in several books, probably the most noted was “The Complete Angler” by Izzak Walton. Thorpe also stretched his talents for producing artwork for various adverts such as Bells Whisky, Kodak and Three Nuns Tobacco.

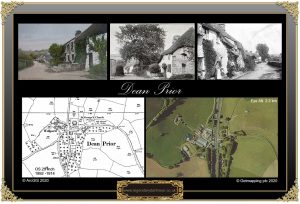

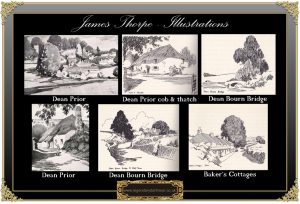

In the Easter of 1900 Thorpe and a school friend, Cuthbert Denton, discovered Dean Prior which he described as being; “one of the turning points of my life.” Denton had fallen ill and been advised by his doctor to take a month’s holiday to recuperate. The doctor’s suggestion was to visit Devonshire which consequently then saw the two friends arriving at Exeter Station. Having no knowledge of Devon they set forth for Newton Abbot and on arrival Thorpe stated that; “one look at Newton Abbott sufficed to show that, whatever its attractions, it was not the place of our dreams,” – not a lot has changed there then. The two men then tried their luck at Torquay and once again decided best not to hang around there too long either. One shared passion that the friends had was the works of Robert Herrick who they knew once lived at Dean Prior so they headed off to the small village. “The Stationmaster at Buckfastleigh was not encouraging. No one, as far as he knew, had ever stayed at Dean Prior, no one had ever wanted to stay there, and even if they had there was no accommodation to be had. This all sounded promising, and leaving our luggage we trudged off to find it. About a mile out we came over the hill, and there in the valley was the village of orchards and whitewashed and thatched cottages, and we knew that this was what we wanted. These three delightful weeks of rest and sunshine restored us all to health. We rambled through the lanes and explored the moor… For me this opened up a new world – a world of peaceful reality after the noise and artificiality of London.” This was the first of many holidays at Dean Prior and in 1911 Thorpe had managed to obtain the tenancy of a cottage at Dean Prior which served as his holiday home. In 1919 he had decided to move from Hertfordshire and take up residence permanently at Dean Prior. Although the small cottage served well as a holiday home it would not do as a residence and so the cottage and the next door old Rose and Crown Inn were knocked into one. The only thing then lacking was a work studio and this problem was solved by locating one in Esher and having it shipped down by train and re-erected in the garden behind the cottage. You can see many of Thorpe’s cartoons and sketched below –

I will now let Mr. Thorpe describe Dean Prior, its characters and the locale as it was back in the early 1900s; – “The first part of the village is Dean Church-town, where a lane turns left over the hill to Dean Combe, the larger part being about half a mile further along the main road, which was constructed in 1835. Two older roads lie further west in order of antiquity. Most of the cottages, beautiful in their simple style and design, are built of cob – a mixture of earth, straw and stones – with walls three feet thick, thatched roofs and deep-set doors and windows, many of which retain their leaded lights. Some of these cottages have changed little since Herrick’s day, but there is little doubt that very many have disappeared, and old maps confirm this theory. Even in the last thirty two years two at Church-town and one at Dean Combe have been allowed to fall into ruin. A row of five was destroyed by fire a few years ago, and now road widening threatens five more.

Many narrow winding lanes intersect the main roads and lead past farm houses and orchards up to the slopes of Dartmoor, which extends northwards and westwards fro twenty miles in much the same state as God made it. The banks and hedges often fifteen feet high , which shut in these lanes, from March to June are a tangle of ferns and wild flowers, fairer in their indiscriminate confusion than any well-ordered garden. Masses of snowdrops, anemones, daffodils, primroses, bluebells and foxgloves appear in a sequence of gorgeous profusion, and in May the village, seen from the hills, seems to float in a lake of pink and white apple blossom. Then for a few weeks we are very near to Arcady, Dean Wood – in local parlance ‘Dayn-od’ – extends for two miles along the steep sides of the narrow gorge through which flows the Dean Bourn – Herrick’s ‘rude river’ – which rises on the moor near Hayford, dashes over two falls, and, after a course of about four miles joins the Dart at Buckfastleigh.

Polwhele (1760 -1838) writes of this; ‘The vale of Dean-Burn unites the terrible and graceful in so striking a manner that to enter the recess hath the effect of enchantment: while enormous rocks seem to close around us, amidst the foliage of venerable trees and the roar of torrents. And Dean-Burn would yield a noble machinery for working on the superstitious minds under the direction of the Druids.’ There is nothing known to Justify the surmise of the workings of the Druids, although half-way up the wood is a large flat rock, known as ‘Knowles’s Table’, which might conceivably have served as a sacrificial altar… Just inside the parish boundary a hedge of Potter’s Wood was formerly a chalybate spring called St. Catherine’s Well, much frequented as a cure for sore eyes and other ailments, but this was diverted when borings, fortunately unsuccessful, were made for iron. Everywhere are little rapid streams, and the pleasant murmur of running water is never far distant.

There are several old stone crosses in the parish, many of them being in the nature of early directing-posts, with the initials of the towns cut in the sides. Moor Cross near Dockwell shows the roads to Ashburton, Totnes, Plymouth and Tavistock. On the moor, just inside the boundary which separates us from the Duchy of Cornwall estate, is Huntingdon Cross which marked the Abbot’s Way between the Benedictine Abbeys of Buckfast and Tavistock. Most of the fields are small, less than twelve acres. and divided by earth banks and high hedges or stone walls. Some of the beautiful old field names still in use are of more than local interest; Brim Park, Brimmy Down, Stray Park, Warm Park, Furze Park, Conduit Park, Colly Park, Sanctuary, Shepherd’s Field, Bow Down, Shin Park, Green Close, Graydons, Linhay Field, Windsor’s Field.

In a great measure we are self-supporting. We have a mason, a wheelwright, a carpenter, a blacksmith and a thatcher, all who know their jobs and can do them well without the interference of the trade unions. Our shop, although it measures little more than six feet square, contains a marvellous stock of all the vital necessities, including tobacco and matches. At the schoolhouse a hand loom used to produce excellent home-spun tweed; and I am still wearing a jacket of this cloth woven twenty-two years ago. Much of our food is produced in the parish, and there is no need of preservatives nor danger of adulteration. Before the war we used to make our own cider and much more, and two massive oak presses still survive; but this, like so many other old customs, is now a thing of the past. The apples are sent to the factories and we have to buy our own cider. Our water supply comes from an excellent spring that never fails us in the longest drought; and although there is no modern sanitary system, we escape the epidemics that attack the more enlightened town. It was only a little more than a year ago that, despite determined opposition by out postmistress, a telephone was installed.

Although we receive a few visitors – mostly pilgrims, some from overseas – to the church of Herrick, we have so far escaped the tripper, who I fear find us sadly lacking in ministering to his creature comforts; for we have no tea-shop and not even a public house in the village. In August a few strange people in fantastic garb descend upon our quietude, regard us with condescending and compassionate forbearance, and indulge in fulsome and ecstatic praise of the joys of country life. But they never come in winter! Only thirty years ago we had a resident witch; and one of our farmers used to declaim lustily against railway trains, in which he firmly refused to ride. I tremble to think what he would have said about motor cars. Until quite recently the village and its people remained unspoilt and unsophisticated, but newspapers, increased transport, and wireless installations are all working great changes…

Local characters whom I had known as acquaintances now became more intimate friends. The old parson (C. J. Perry Keene) who had fathered the parish for over forty years was a constant visitor, and together we complied a history of the village which, at his death, was just ready for publication. In fact the publishers agreement arrived for his signature on the morning he died (the book called ‘Herrick’s Parish, Dean Prior’ was indeed finally published in 1927) . He was a delightful character, with a short, compact, sturdy figure, a fine head and a sense of humour, a loving admiration of his great predecessor, and a kindly, genial outlook on life. At Oxford he was runner-up for the light-weight boxing championship, and achieved some renown in hurdle-racing and rowing. He was the Grand National Archery champion in 1898 and an excellent game shot, maintaining an active interest in both sports until the end.

A local character of a very different type was John Full, a survivor of the old school of farm labourers. He had never gone to school, had started work at seven years of age, and never been in a train. He worked hard through all the successive tasks of the farmer’s year, doing his job, as he had always done it, with pride in his skill, and having no concern about that of others. He spoke the pure broad musical Doric of Devon with much simple sense and sound philosophy ‘Sufficient unto the day’ was his simple rule of life, and his principal creed included only the possession of money enough for beer and baccy and an undisturbed willingness to let the rest ‘take thought for the things itself’. From a weathered face, deep red, lined by the years, and strong in character and hard experience, looked out a pair of merry blue eyes. His old “ard ‘at’ covered a thick shock of white hair which was continued below his chin by a rough fringe beard. He always carried to his work the wooden keg of cider, which he would drain with ease at a short sitting, and was much attached to a short black clay pipe packed with potent shag, which he gripped firmly between his toothless jaws.

It was at the ‘Half Moon’ over his evening pints (and they were many) that he was at his best. At first he was difficult to draw out from his grave contented dignity, but once started he was entertainment for the night, with long memories of Dean, stories of field and farm-house and their inhabitants, supreme contempt for the modern idolatry of sport and his songs of a forgotten age. For in those happy, far-off days we were allowed to sing in pubs, and each man had his own particular song or songs, his right to which was never disputed or infringed… In the early days we tried to lure the old chap to London for a holiday visit, ‘Well,’ he said, ‘I’ve a-thought sometimes I’d like to see this yurr London, but mother and me, us have talked it over and us be come to the con-clusion that old England be good enough for we.’ After that there was nothing more to be said. At seventy ‘the rheumatics’ got him and he was very reluctantly compelled to ‘bide ‘ome’, living on his old age pension. Later, misfortunes of various kinds overtook him and at the age of seventy seven, his end came sadly and ingloriously in Totnes Union. A fine specimen of a type which we have seen almost completely disappear in twenty years.

Of these splendid people who happily are still with us it is difficult to write, but of one I must, and I hope he will forgive me. His real trade is that of a wheelwright, and he is a skilled craftsman, but forty-three years of service at the farm, and a diminishing demand for carts and wheels, have made him sort of general factotum, who can be implicitly trusted to do any sort of job, and do it well, from driving children out in his pony-trap, to collecting tithes. The only holiday he ever wants is a visit to a race meeting and he has never been heard to resent his return to work. His two hobbies are food, which includes beer, and racing, with minor interests in any form of real sport, and to these he is wholeheartedly devoted. Breakfast comes late after two or three hours’ work and may consist of a large plate of stew, fat pork, fried bacon and eggs, or fish, these last often flooded with vinegar. Lunch and tea are negligible meals, but some good work is put in at night as a sound basis for a good spell of undisturbed sleep. To see his plate covered to a depth of three or four inches with a varied assortment of meat, vegetables and dumplings (plain or apple) and to see this cleared in record time is enough to cure any dyspeptic. Pie-crust and hot cakes are side-lines which can be disposed of in odd moments. On Sundays he is indulged with some hot water for his morning bath which on other days is always taken cold. If the weather is bad, he ‘bides where he is to,’ but in normal conditions he accompanies ‘the missis’ to church, for as he wisely puts it ‘you can get anything out of her then.’ If his enthusiasm for the things he loves is whole-hearted, so also is his hatred for those of which he disapproves, such as teetotallers, professional football, labour leaders, ‘sympathy concerts’, bigotiveness, politics, and those sad people whose only interest in life is the accumulation of money which they don’t know how to spend. They have never been anywhere, never seen anything; their pride is in a front parlour, a stuffy, overcrowded room which they never use; and their only idea of enjoyment a day at the seaside sitting on the sand. Women are all very well in their way, but they must be kept in order, and he knows exactly when to ‘put his foot down’ – if, for example, anything is wrong with the food – and when to ‘play light’. He has a vocabulary of his own, much of it in broad dialect, and the defective pronunciation by B.B.C. announcers of foreign names of racehorses is one of the few things in life that depresses him. Bach for him is ‘Batch’, and Tchaikovsky – well people ought not to have such names. For politicians of all shades of opinion he has no use unless by chance they also own racehorses. Their specious promises and meaningless speeches, their failure to grapple with any of life’s real problems, or to reduce the price of beer and tobacco, their proposed solutions of the agricultural problem by small holdings, these he treats with utter scorn.

When war was declared he was forty six years old, but as an old volunteer he joined up two days later, although he admitted afterwards, ‘If i’d a-knowed what I know now I’d never a-went.’ He was in France in November and thus qualified for his Mons Star which his proud wife always has to find when it is wanted. He did ten months in the front line and then his age defeated his pluck and he was invalided home. In that time, amongst other jobs, he carried a man back from a dressing post to a clearing station and finally to hospital, a distance of seven miles. On arrival he was, to his great surprise, packed into bed himself, well fed and physicked, and very closely watched. The man he had brought in was a bad case of typhoid, and when they told him how far he had come his only reply was, ‘It seemed a long way!’ After a spell of home service, which he regarded as a waste of time, he managed to get his discharge in July, 1917, and has ‘lived happy ever after.’

Life for him is a joyous experience; each day produces its supply of fun. and tomorrow or the day after doesn’t matter. In spite of his sixty-five years he remains a boy and his sense of humour satisfy him. He loves the children, as they instinctively love him, ‘chips’ the women, and pulls the legs of men who take life far too seriously. He is by far the happiest man I have ever met, and the soundest philosopher, and both virtues proceed from good health and a great spirit of contentment.” – pp. 201 – 221.

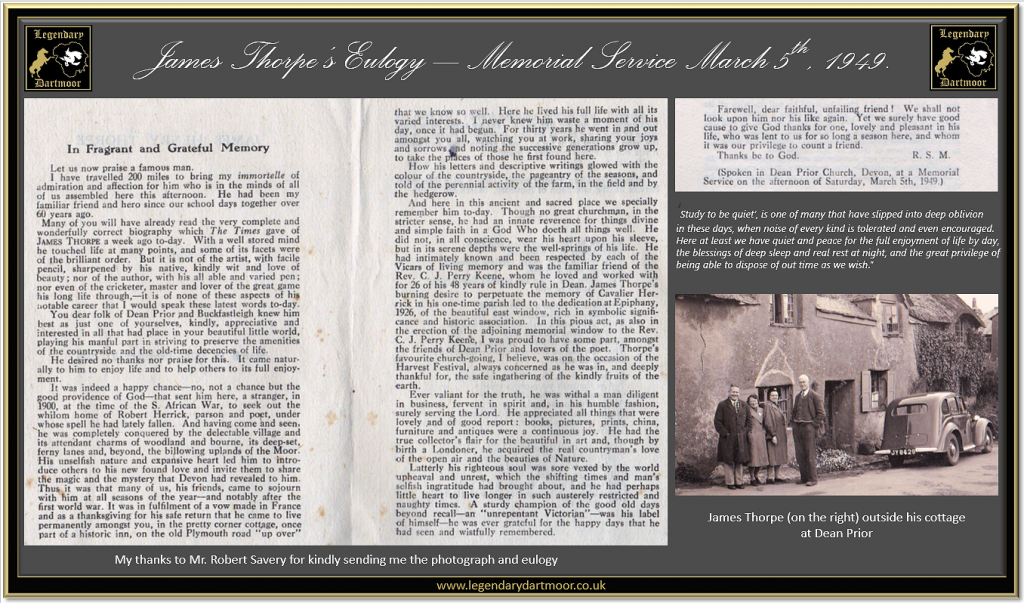

James Thorpe died at Newton Abbot in the March of 1949 and a memorial service was held in Dean Prior church on the 5th of March. Due to his love of cricket and being the once-time captain of the Dean Prior cricket team his ashes were scattered on the Buckfastleigh cricket field prior to the memorial service. A copy of the eulogy read at the memorial service can be seen below along with a photograph of him and his wife standing outside their cottage. From left to right – Dr. A .T. Bettison of Didworthy, Bunty Bettison, Mrs. Thorpe, and James Thorpe. On thing that certainly stands out in the picture is how tall James Thorpe was. My thanks to Mr. Robert Savery for kindly sending me a copy of the eulogy and photograph and allowing me to use them.

He left behind a legacy of numerous cartoon and sketches which today at auction can fetch several hundreds of pounds. In addition to his artwork and beside ‘Happy Day’s he also published other works such as; ‘A Cricket Bag’, ‘E. J. Sullivan’, ‘Come For a Walk’ and ‘Phil May’. But as you can see above, moving from a city life to the quiet backwaters of Dartmoor had a profound effect on his life. He rapidly absorbed himself into the life and lives of Dean Prior as well as enjoying his passions for cricket, angling and in later years golf. What he would make of Dean Prior today is anybodies guess but I have the suspicion he would not be too impressed. One small final aside, it seems that not everybody Thorpe came across were honest country folk. On the 22nd of October 1932 a man knocked at Thorpe’s door and said that he and his seven friends needed to get back to Avonmouth to join their ship. At first the man tried to sell a rug but on refusal produced two rings which he said he had bought back from Persia and they were worth between one hundred and one hundred and fifty pounds. He then offered them to Thorpe for £25 and said he could dispose of them himself and anything over that they would share, again the deal was refused. Then the price for the rings dropped drastically to £8 and feeling sympathy for the men and his friends he gave the money. At a later date he took the rings to a jeweller in Totnes for a valuation, sadly the jeweller said they were worthless. Eventually the matter ended up before the Totnes magistrates with one Alfred Spencer being charged with obtaining £8 with false pretences from James Thorpe. Spencer was found guilty and fined £5 with costs or one month’s imprisonment.

I will let Mr. Thorpe have these final words on living at Dean Prior; “Old Izzak Walton’s maxim, ‘study to be quiet’, is one of many that have slipped into deep oblivion in these days, when noise of every kind is tolerated and even encouraged. Here at least we have quiet and peace for the full enjoyment of life by day, the blessings of deep sleep and real rest at night, and the great privilege of being able to dispose of out time as we wish.”

Thorpe, J. 1933. Happy Days. London: Gerald Howe Ltd.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Once again, a fascinating vignette of life on the Moor. I look forward to the Digests and although I can understand the reason, I shall miss reviving them. Thank you for your wonderful website.