It Should Never Happen to a Vicar – Gidleigh is a quiet picturesque village on the eastern side of the north moor and is noted for its ancient castle and church. As with many things “every rose has its thorn,” and in the case of Gidleigh it was the Reverend Arthur Peregrine Whipham. The Gidleigh estate was purchased by Dr. J. Whipham in 1819 and was the family estate for nearly one hundred years.

In 1832 Arthur Whipham achieved his Bachelor of Arts degree from Trinity College, Oxford. In the December of 1834 Arthur Whipham BA., Trinity College was ordained a priest by the Lord Bishop of Gloucester at Gloucester Cathedral. In 1836 he became the rector of the Holy Trinity Church at Gidleigh, a post he was to retain until 1862 On the 17th of August 1843 he was married to Frances Huxam a solicitors daughter from Bishopsteignton which was to be the beginning of this sad saga. During their early marriage they had eight children, sadly their daughter Clara died in 1851.

In the October of 1858 the Reverend Whipham was sued at the Crediton County Court by a merchant5 from that town for non-payment of goods sold and the interest to the value of £8. 15s. – judgement was entered for the plaintiff. This was the beginning of what was to become a well-versed acquaintance with the judicial system.

On the 22nd of June 1861 the Rev. Whipham appeared at the Exeter County Court where a Mrs. Sparshott of Southernhay had summons him for the recovery of £47. 4s. and 6d. This sum was in respect of the lodging and board for his wife and daughter along with a loan for some clothing. A Mr. Froud for Mrs. Whipham’s defence stated that around 1858 Mrs. Whipham, being in a state of ill health left her husband and was given an allowance of £1 guinea a week. Six months later the allowance was stopped and from then on she had managed to exist by her own means and lived with her parents for a short time until they refused to support her anymore. After taking advice she notified her husband that she would return to their house at Holy Street in Chagford. She soon found that the house was damp and unfit for habitation and that her husband had instructed the staff leave the house and to have nothing to do with her and then he left for London. At the time her nine year old daughter was in a state of ill health and the only support she got was from an old family servant, Mrs. Betty Govier for two to three weeks. At this time she could get no local credit and left with just one habitable bedroom and no money for food. On the advice of her proctor she moved into Mrs. Sparshott’s lodging house ion Exeter. After a month a claim was sent to the Rev. Whipham for the costs of the board and lodgings along with some money she had been lent for clothing. The Rev. Whipham replied that he was not liable for the monies, hence this case.

Mr. Froud then cross-examined Mrs. Whipham where she stated that after her allowance had been stopped she went to teach the children of Mr. Saunders, the Archbishop of Canterbury for the sum of £1. guinea a week. She then moved to Germany to stay with her father and stayed there until the January of 1860. Then she moved back to London where she stayed at her mother’s lodgings until May when her mother moved to Spain. Following her mother’s departure Mrs. Whipham travelled to Ostend where she taught Prince Doria’s family until the October when she returned to Holy Street. Again she confirmed much of Froud’s opening statement adding that when her husband returned from London he ordered all the bedroom furniture to be taken to a labourer’s cottage called ‘Leigh’. Finding herself in dire circumstances she sent a letter to her husband via a woman called Becky Bourne, it read; “Dear Arthur – Your conduct obliges me to write to know the cause of your unmanly and cruel treatment of me and your child, by deserting us, withholding from us proper support and keeping us in a house which you know is not fit to live in. I wish to know if it is your intention to render us suitable support; if not I have no other course but to begin proceedings against you.” Needless to say there was no reply to the letter and Mrs. Whipham and her daughter moved to Mrs. Sparshott’s lodgings.

Having related her pitiful story it then was the turn of Mr. Fryer for the defence to cross examine Mrs. Whipham where circumstances took a sudden turn. Mrs. Whipham stated that the first disagreement in their marriage took place in 1857 and concerned “a gentleman living at Moretonhampstead.” and following later disagreements she left her husband in 1858. The reason for her departure was given as “improper behaviour of Mr. Whipham with a common servant girl.” as confessed to her by the girl herself in the June of 1858. There was also an accusation that her husband had caught a ‘disease’ from the girl. In that September rumours had reached the Rev. Whipham via “wicked men,” that there was a connection between his wife and another clergyman of the neighbourhood. There was some degree of reconciliation until Mr. Whipham’s imprisonment in 1859. This sentence was for contempt of the Court of Chancery regarding a bond he gave for his brother. The upshot of all this was that Mrs. Whipham, due to the circumstances noted above moved into Mrs. Sparshott’s lodgings. The decision reached by the judge was; “I am of the opinion that Mr. Whipham’s conduct in leaving his wife without any provisions, and quitting the house at night, unprotected by any man and without reasonable excuse for him going to sleep in another house in the neighbourhood, was such conduct as to justify Mrs. Whipham in seeking a home elsewhere. Judgement for the amount claimed.”

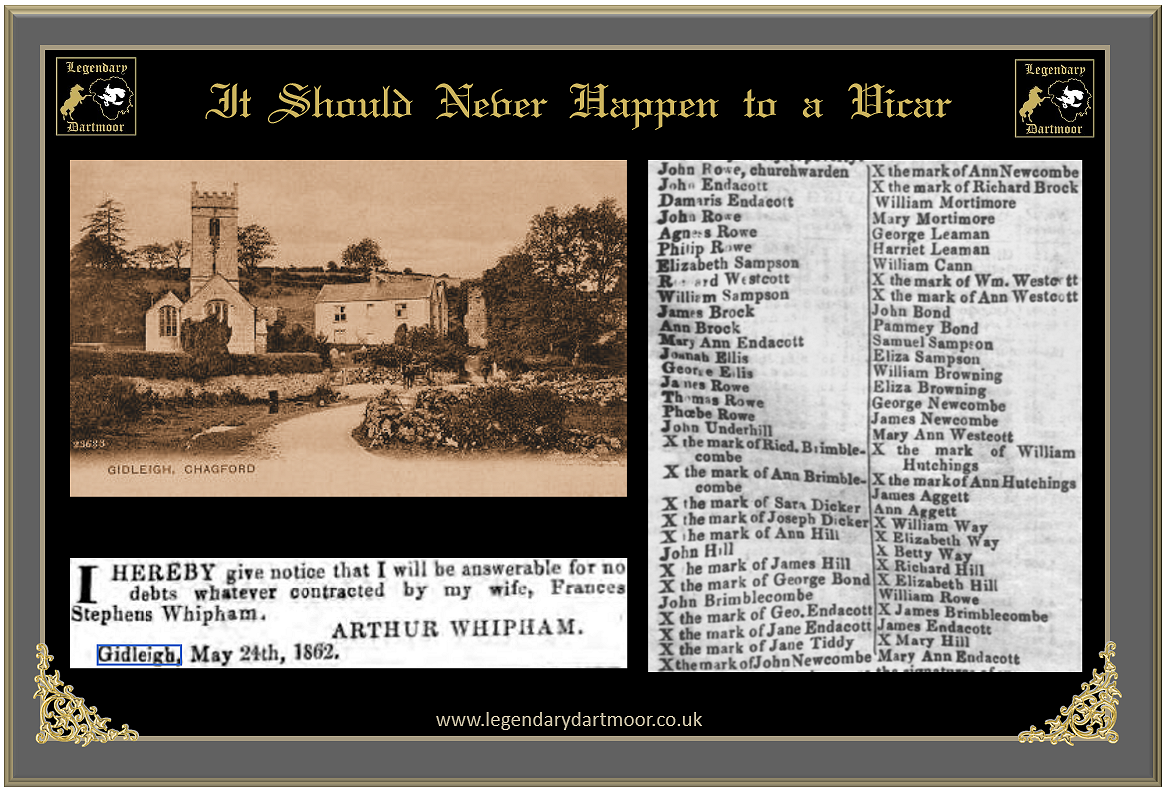

Following that court case in the July of 1861 the churchwarden on behalf of all the adult parishioners of Gidleigh wrote a letter to the Exeter & Plymouth Gazette testifying to Whipham’s good character, it read: “Sir, – Our esteem for our respected pastor, who had been publically accused of immoral habits, and convicted for cruelty to his wife, induces us to request you insert the following declaration in your next paper.

We, the undersigned, being all the adult inhabitants of the Parish of Gidleigh, hereby declare that the Rev. ARTHUR WHIPHAM during the last 26 years that he has been our beloved Rector, has never, to our knowledge and belief committed one single act derogatory to his character as a clergyman and gentleman.

We consider the Rev. Gentleman to be a man of the highest integrity, scrupulously strict in his morals, and of a kind and benevolent nature.

The patience which he has submitted to gross and repeated provocations from his wife, which several of us has witnessed, are well-known in the neighbourhood. We believe him to have been a forgiving and indulgent husband, and his devotion to his children proverbial.

We have felt for him under his pecuniary difficulties which we understand to have been increased by acts of kindness to a deceased brother, and we now fear the course pursued by his wife against him will reduce himself and family to abject poverty.” – all the signatories can be seen above.

In the July of 1862 the Rev. Whipham found himself at the Exeter District County Court answering an action brought against him by Messrs. William and James Pearse, general drapers from Exeter. This was for the recovery of £16 0s. 7d. which was for clothing supplied Mrs. Whipham on his account. There followed a lengthy discourse as to whether the clothing she purchased was necessary and if so should the reverend be liable. The judge examined the bill which was for a cloth mantle, four pairs of coloured crepe gloves along with other articles to ascertain if they were necessary whilst living at a farm house. In the end the judge decided that the reverend Whipham was not liable for his wife’s debt.

Shortly after the above court case Whipham left Gidleigh and was replaced by the new rector Owen Owen. It was said that just before his departure the attendance at his church services had dwindled dramatically.

On June 12th 1863 Arthur Whipham presented a petition the dissolution of his marriage at the London Court of Divorce. The grounds of the petition were that of his wife’s adultery with Phillip Rowe, farmers son, residing at Berrydown, a farm near Gidleigh. James bird, policeman in the Devon Constabulary gave evidence stating that he was “stationed in the neighbourhood of Gidleigh, I knew the petitioner who was the rector of Gidleigh. On the 31st of August, having been instructed by Mr. Whipham, I saw a man named Hill. From what Hill told me I went to Mr. Whipham’s house. Hill accompanied me to the house. I also saw Mary Hill and Joseph Dicker. It was about half past twelve at night, I told Hill and Dicker to remain outside. I went to a bedroom, having first taken off my boots. I opened the door and by the light of my lantern saw Phillip Rowe and Mrs. Whipham jumping out of bed. Mrs. Whipham came to the door to push me out. She told me not to come in. She raised an alarm and awoke the child who was sleeping in the cot. I told her not to be frightened; that I was sent by Mr. Whipham. Mrs. Whipham had her nightdress on when she came to the door. Her bosom was open. Rowe had only his shirt on, he was behind the bed and afterwards he got under the bed. I pulled him out from under it. I made him dress, his boots were in the cupboard which was shut, I took him to Mr. Whipham. He said; “I would not be caught for £300.” Several other witnesses collaborated the policeman’s evidence and the judge pronounced a decree nisi with costs against the co-respondent.

The Reverend Arthur Peregrine Whipham died in the November of 1882 only to reappear in the November of 2011. In the October of 2011 an extensive restoration project was being conducted at Gidleigh Church. During the work a small loose stone was discovered in the floor of the chancel and on its removal a long forgotten medieval crypt was discovered. By lowering a fluorescent light down into the crypt and with the aid of a mobile phone camera it was revealed that there were two coffins inside. One of them was an adult-sized lead coffin and the other a child’s small wooden coffin. Chris Chapman, a local photographer and historian was notified of the discovery and immediately went to the church – “The hole through the floor was very small, so I put the widest lens in my possession onto my stills camera and squeezed the two into the chamber, ensuring that the camera strap remained firmly round my wrist. By the light of the tube, and with the ISO set high, I pressed the shutter again and again, shooting blind but carefully scanning the camera around the crypt. Back at my studio I examined the results.

he ‘lead’ coffin was curious. At some point it had been dropped, but the character of the indentation was not what you would expect from lead. I searched on the Internet for the invention of galvanised iron and discovered a date of 1837. If this was a ‘ tin’ coffin then who ·on earth did it contain? Older gravestones, dating from the 17th century and later, had been placed against the outside north wall of the church and are known to have been removed from the floor of the nave. Directly under the chancel screen my photographs also revealed an arched doorway and steps, now blocked with granite but once leading up into the central aisle of the nave. I processed the pictures and sent them to the church architect Allen Van der Steen, expressing my belief that the adult coffin was in fact a galvanised one and not lead, as was first thought.”

The loose stone was then replaced and mortared in but a few days later due to the workmen trundling wheelbarrows to and fro a small portion of the crypt’s roof collapsed. The resulting hole was big enough for someone to get through so Chris Chapman returned to the church. “Donning a hard hat and with a mixture of excitement and trepidation, I asked to be lowered in; and, careful not to disturb anything, I cast my eyes around. Beyond the child’s coffin and towards the east window was evidence of another small chamber, and on examination the block of stone that prevented a view inside was unmortared, displaying the familiar stonemason’s marks of feather and tare and hinting at a 19th-century disturbance. The crypt itself had been limewashed, and what I had thought to be curious black ‘corbels’ on either side of the arched doorway was in fact black paint, which continued up and onto the nave side of the granite arch The adult coffin was indeed galvanised and, on lifting the lid, another coffin was revealed, made of oak and with a heavy brass plate naming the deceased as ‘Aurthur Whipham Born July 6th 1810 Died November 18th 1882.” Clearly whoever engraved the brass plate had an issue with their spelling. – Many thanks to Chris Chapman for sending me his article which appeared in the summer 2012 edition of the Dartmoor News.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor