Over the centuries numerous ‘adventurers’ have tried to get rich quick with various schemes and notions on Dartmoor. Looking back on most of them one can’t help being grateful that they never came to fruition. An excellent example was the scheme of Mr. H. J. Halford which had it gone ahead successfully would have meant the extraction of several millions tons of Dartmoor peat from around the northern fen. Today numerous efforts are being made to restore the moorland peat bogs and mires which is no easy task but imagine how much harder it would be if there was no peatland to restore and the consequences for climate change?

At the Duchy Audit Dinner held at Princetown in the October of 1936 Lord Radnor, the Lord Warden of the Stannaries of the Duchy of Cornwall hinted that an old Dartmoor industry might be revived. He said; “I refer to the re-opening of the peat works at Rattlebrook, I hope and believe that that may lead to a considerable amount of employment and industry on Dartmoor.” Here he was alluding to a new and ambitious scheme put forward by a Mr. H. J. Harford for a new distillation plant on the site of the old peat works.

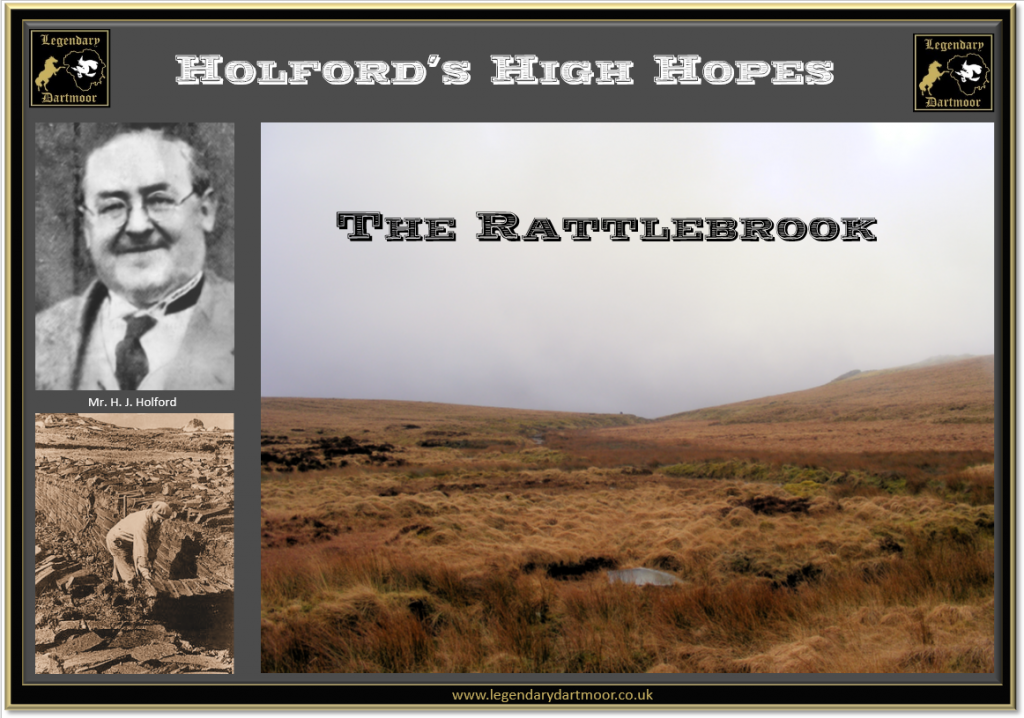

Mr. Holford lived at Whitchurch near Tavistock and in 1933 he began examining how various by-products of peat were being extracted in Germany and Sweden. This then gave him the idea that such methods could be profitably used on Dartmoor. With this in mind he began his research in London where he invented and perfected a distilling process whereby he could efficiently convert peat into various products. A lease was granted in the July of 1931 to Mr. H. J. Holford and Mr. A. M. Stray of the Holford Processes Ltd. of London from Major Calmady-Hamlyn and the Duchy of Cornwall for six miles of the old peat tramway. One of the conditions of the Duchy of Cornwall in granting the lease was that local labour and materials were to be used as far as possible. The company also obtained a lease for 360 acres of land granted by King Edward. Originally he had hoped to begin his work at the end of 1931 but the death of King George held up the process until a new lease was signed Having convinced himself of the viability of his process he then spent many months tramping over the northern moor in search of a suitable location to set up his works. Finally after testing the peat he settled upon the area around the Rattlebrook which for centuries earlier had been used for peat extraction. The initial stage of the plan was to completely demolish the old works and build new ones. It was planned that this operation along with relaying railway lines and building bridges should start in the early days of November 1936.

The big difference in Holford’s method of distillation was that the peat did not have to be dried. Instead to put the wet soggy peat straight into retorts where low-pressure and super heated steam was then injected into it thus creating a hydrocarbon-laden vapour. This was then condensed where gas, crude oil and other chemical substances were obtained. It was envisaged that the gas produced would be used to power the plant. This meant, as with earlier distillation processes, no charcoal needed to be purchased and the plant was self-sufficient. Additionally no fumes or smoke was produced and there was no need for unsightly chimneys which could spoil the moorland aspects.

Harford projected that each ton of peat would produce around 50 gallons of crude oil from which he would get 30 gallons of fuel oil, 20 gallons of pure petrol, 6cwt. of ordinary charcoal and 50lb. of activated charcoal. The plan was to have four retorts which would be working night and day by the end of the summer of 1937. This could mean 35,000 gallons of crude oil could be produced each week and eventually increasing to 100,00 gallons a week. He also envisaged that once hardened the charcoal was a valuable resource for smelting purposes and the activated charcoal for the purification of organic substances.

Discussions were held with both the Air Force and the Admiralty with a view to using his products as fuels which due to a minute percentage of metals acted the same as leaded petrol thus making it ideal as a fuel for aero engines. With the events in Germany at the time there was a possibility that another war may break out. With this in mind Holford saw an important market for his activated charcoal. Previously this was being imported for use in gas mask filters but supplies were becoming hard to source as they were being needed for use in their own countries. Along with the fuel oil and charcoal acetic acid, acetone, methyl alcohol and sulphate of ammonia would be recoverable from the surplus water left over after distillation. The purified peat tar left by the process could have been used in the manufacture of disinfectants and a wax used in embrocation and soap. Probably the most adventurous part of Halford’s plans was the construction of a pipeline to carry the fuel oil directly from the Rattlebrook area to Devonport Dockyard for naval use. Looking to the future Halford estimated that there were several millions of tons of peat on Dartmoor so plenty of room for expansion into other moorland areas. He also considered that should the supply ever get exhausted then there as always the opportunity to regrow more peat from the various mosses – although that would “take some time“.

During late 1936 through to around 1938 both the national and local press were inundated with articles of Holford’s proposals along with sensational headlines such as, “Oil field on Surface of the Earth“, “By products from Peat“, Peat for Oil Fuel“, Along with the reports many letters of concern appeared. In the January of 1922 the Dartmoor preservation Associated submitted a long letter to the Exeter & Plymouth Gazette the main worries being; “To bare Dartmoor of peat over any area would be a fatal mistake. To work the small deeper beds would do relatively little harm, although still undesirable. If, however, it ultimately appears that there are deep deposits at once larger and more numerous than is now thought, then working them except of a small scale would be most harmful. Grazing and water supply alike would suffer. At the moment, and until the matter is further developed, the chief necessity seems to be to observe the works and to note at once should any deleterious waste products of distillation find their way to the streams or rivers. This is a very possible danger.” – January 22nd. In the March of 1937 Colonel C. Marwood Tucker, a Devon County Councillor commentated that; “Many people well able to judge believe that the extraction of peat from Dartmoor on a large scale will seriously interfere with the flow of the rivers from the moor, for the reason that peat overlying the granite of Dartmoor absorbs and stores the whole of the water which forms the rivers rising on the Moor. Under this peat or soil are granite or sand in which there are no springs and which allows water to filter through without storing it. The rivers flowing down from Dartmoor are noted, speaking generally, for their absence of flooding and their fairly regular flow even in dry summers. This is attributed to the fact that they all come from these “sponge areas” of peat in which water is stored.” – The Western Morning News, March 23rd. Other concerned parties were the Devonshire anglers, people relying on water from the area and Dartmoor lovers in general.

By the November of 1937 the old railway line had been cleared of gorse and heather and old bridges demolished for what was then known as Harford’s ‘Peat Extraction Company’. Mr. A. Arscott was in charge of the work and predicted by the Christmas of 1937 new sleepers and rails would be laid. Once the railway was complete it was intended to build the factory at Bridestowe and transport the peat down from the Rattlebrook for distillation. One of the reasons for this was that the 150 men needed to man the factory would suffer from the cold temperatures at the high elevation of the Rattlebrook during the winter months. It was also intended to set up petrol pumps at Bridestowe where people could by ‘Dartmoor Petrol’. Amazingly Harford had been approached by an interested party who wanted to establish a ‘peat spa’ at Rattlebrook where people could come and wallow in it. By 1939 work was still progressing on the railway but Harford had found a new venture – pig food. By mixing the peat with molasses it was successfully being fed on a 400 pig herd in Somerset. By the March of 1940 the Second World War was affecting the supply of coal. Added to this many of the men who used to cut the moorland peat were away fighting which along with a wet summer meant a huge shortage of peat for domestic heating and cooking. So bad was the situation that Harford was actually cutting his peat for use in his home. Despite several requests to cut more peat for domestic resale he flatly refused as all of it was to be used in his factory when it was finally completed. Another setback to Holford’s works came when much of the area around the Rattlebrook being commandeered by the military for training purposes which made access difficult. Then just a quickly as the Holford Processes Ltd burst onto the scene it vanished just as quickly around 1946, never to be heard of again. The Duchy did issue one last lease for the area in 1955 to Messrs. Renwick, Wilton & Dobson. They were extracting peat and selling it as granulated peat for horticultural purposes but again the business folded as it was not profitable. (Harris, 1986, The Industrial Archaeology of Dartmoor, p. 115.) Yet again one can’t help being reminded of the old Dartmoor adage – “you scratch my back and I’ll tear your pockets out.” A warning that has proven only too well for many past failed ventures where people have tried to make money from Dartmoor’s natural resources.

The Devonshire Trust in conjunction with the Dartmoor National Park Authority, The Dartmoor Preservation Society and the Duchy of Cornwall initiated the Magnificent Mires Project. As part of this there are four suggested walking routes around some of the moorland mires, one of them being from Lyd Head to the Rattlebrook. Interestingly enough their concerns of today are very much what was predicted back in the late 1930s. “In the past, activities such as peat cutting, over-grazing and burning, military usage and recreation have caused damage and erosion. As the habitat degrades, the ability of the bogs to deliver the services vital for local communities declines. Reduced biodiversity, poor water quality, carbon release and the loss of important historic records which span millennia are all a result of bogs drying out and eroding.” – follow above link.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor