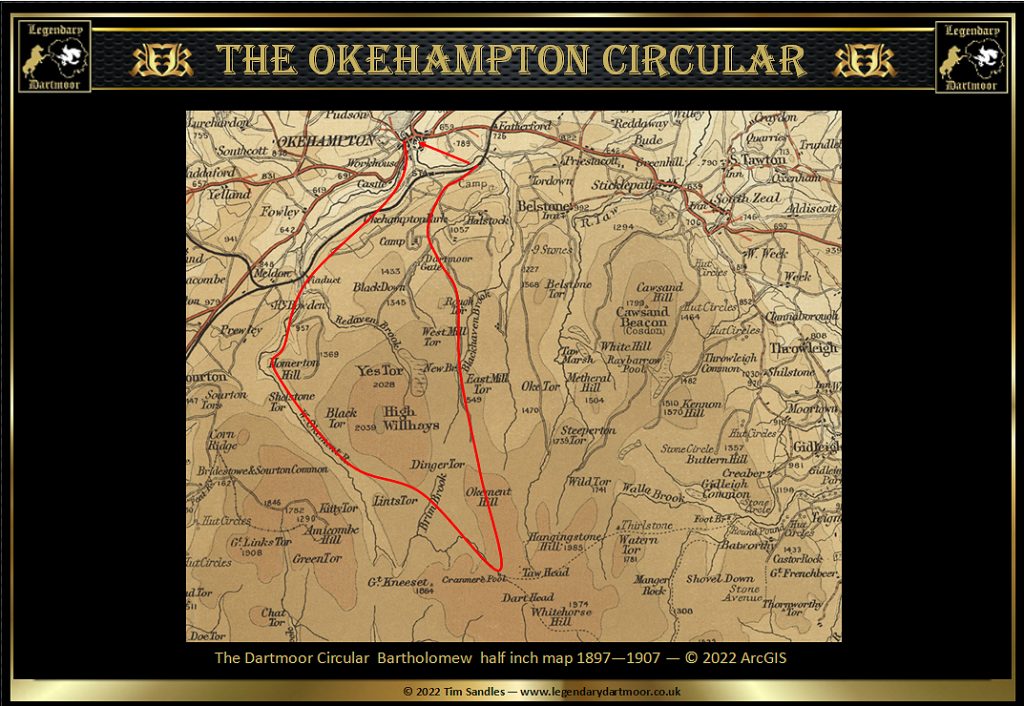

What follows is the account of a 16 mile walk taken in the October of 1887. Today parts of this trail would be impossible as it would mean strolling beneath the Meldon Reservoir and therefore unique in its content. Nevertheless it is a fascinating account of the sights and experiences along the way and a great insight into the landscape of that era. The bracketed comment in blue are modern day interpretations and the bold black names are links to further information on the subject from website

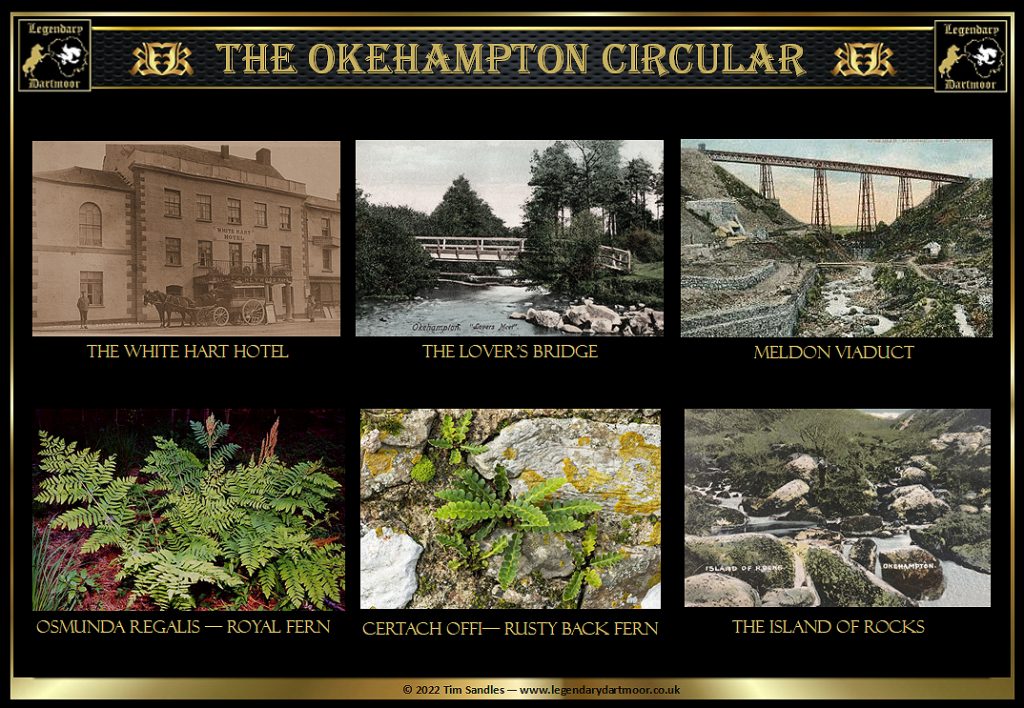

“‘Tis a glorious morning as we leave the old town of Okehampton, past the modernised and convenient hostelry, the White Hart, and so along castle lane and through the workhouse grounds, over the stile beyond and into Okehampton Park. The East Okement river, bounding and sparkling as it rushes over rock and boulder, cannot fail to claim attention, nor must the wooden bridge close under the castle, and generally known, perhaps deservedly, as “The Lover’s Bridge,” pass unnoticed. The old castle too stands out well with its dark background of foliage; and hard by the banks of the river, if of a very enterprising turn of mind, the old workings of a disused copper mine may be inspected. But we keep on the pathway which gently ascends the hill, and which in a short time joins the public pathway to Meldon Viaduct which leads through the Okehampton Park and the fields beyond to the viaduct itself. About 200 yards below the viaduct, if fond of botany and ferns, you should do as we do – go down the river, inspect and admire the profusion of wild flowers on the banks and the perfect groves of the Osmunda Regalis, which here seems thoroughly at home. Nor should you fail to notice the coloured pieces of rock perfectly festooned with ivy and with ferns on the opposite bank, which covered with dark fir trees makes a lovely picture. The path lies on the bank of the river, under the viaduct, through the stone cracking works, and past the disused waterwheel formerly employed in pumping out the water in the huge lime quarry which now lies idle. The stone work and the walls here abound with ferns, and amongst others we find the Certach Officinarum. By looking up the little stream (the Vellake) which comes from the Moor and which you have to cross, you will see the bed of stone granulite – a species of granite – which liquifies on being heated, and has been used in some considerable quantity for the making of glass bottles and railway sleepers for exportation to India.

You still keep on the left bank of the river and along a clearly defined path which takes you up over the hill to the workings of a disused copper mine (this was probably the old Forest Mine which was worked for lead and copper, now under Meldon Reservoir); you pass there and cross the small rivulet below (possibly and unnamed watercourse flowing from Corn Hole). The valley from which it comes, as indeed both streams you have crossed, are well worth a special visit. They are in the midst of high ground, and have deep shelving banks covered with gorse and heather, and rocky beds with granite boulders more or less hidden with bracken and other foliage. The path now leads through a small field or meadow partially fenced in, and on the other side you get your first bit of rough ground; but it is only for 100 yards or so, and not dangerous in any way for horse or man. Now the river swings to your left, and as you round the hill, which by the way is known as Slippers Torr, (now more commonly called the “Slipper Stones”), the first view of the far-famed “Island of Rocks” is obtained. Now, although the beauty is slightly marred by a fire which raged in June last in the lower portion of the isle, the work of a too careless smoker, it is a glorious sight. The river in about a quarter of a mile makes a descent of at least 150 feet, and in the midst of the fall is split into two parts – the whole of its course and the island so formed is a mass of huge boulders, covered with richly foliaged stunted oaks and mountain ash, to say nothing of the ferns, bracken, and whortleberry bushes which grow in great profusion. This morning the sight is more than usually charming the water is high, the mountain ash are laden with the coral berries and already the autumn tint is showing on the foliage, and as if to add another pleasure to the scene, blackbirds, thrushes, and the ring ouzels flit in and out of the bushes, disturbed by our approach. As soon as the head of the waterfall is gained a complete change comes over the scene – the cascades and rushing waters are changed in an instant for a rippling brook almost meandering along the pasture – like meadows on either side for some considerable distance in spite of the rugged surroundings. On the right you have as a background Hammacombe Hill (Amicombe Hill), on the left the Blackator Copse. This is worth an inspection; it comprises of about two acres of rocky ground, covered with stunted and twisted oak trees; it is gradually growing smaller from a variety of causes, but no so rapidly as Wistman’s Wood, the other place of woodland on the Moor near Two Bridges. By keeping to the left and picking your path a dry and easy ascent to Blackator can be obtained. The view is distinctly charming; it takes in Yes Tor, Black Down, Merton Hills, (Homerton Hill) the Island of Rocks, Hammacombe Hill, and Sourton Tors, while Links Tors, with the surrounding high ground, stand prominently to the fore looking up the stream.

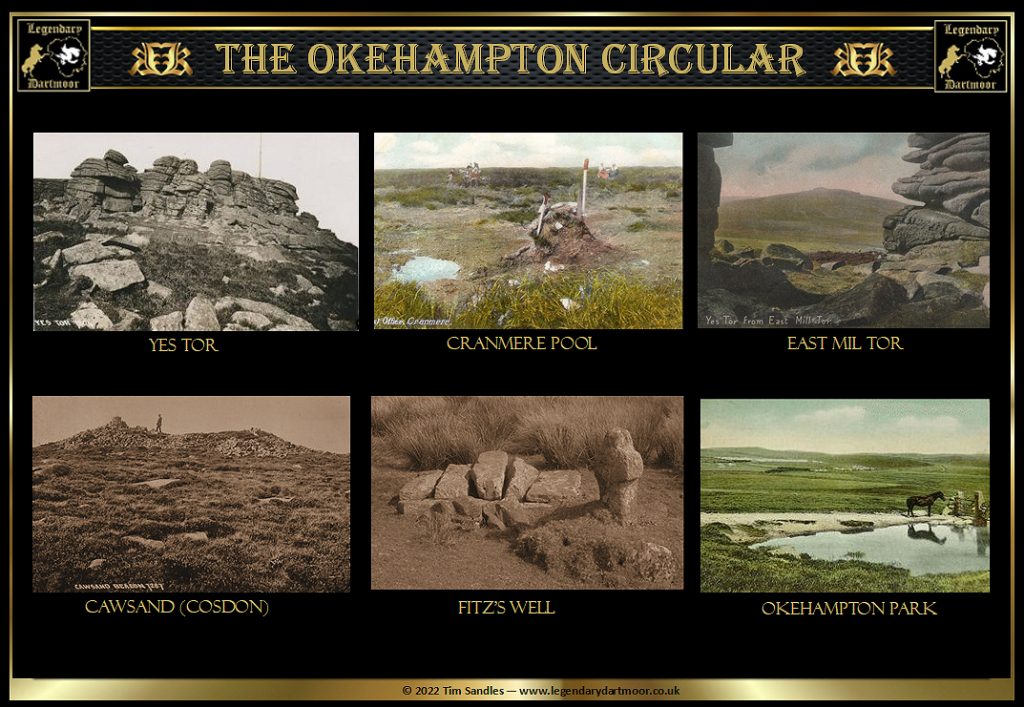

Now skill is required in steering your path to the far-famed Cranmere, which lies about four miles away, the direction being, as near as possible, on your left incline. Your better course is to keep up the Okement towards Links Tor, as the ground is dry and solid, until you see a small stream, which is a tributary of the main stream, the main stream flowing to the right of Links Tor, and this little stream coming in on the left, you do not go down to the little stream, but about 200 yards short of it incline strongly to your left and cross Dinger Hill, leaving the small single rock which points the tor about a quarter mile to your left. You keep on in the same direction for a mile, going over some very peaty land, until you strike another stream. Now, again, is need for caution. If you have followed the exact directions given you will have struck a tributary (the Brim Brook) of our old friend the Okement, which it joins about 200 yards below. The Okement having made somewhat of a large circle, of which we have described the chord, we are carefully guided and cross this stream, go over a small bit of high ground in our front and again hit the Okement. There is a thoroughly sound path along the left bank for a considerable distance until some high mounds of sand are reached; then we cross the water and continue on the right bank of the stream – a stream of very red irony water here comes down the bog, and comes into the river on the left bank. We keep, however, on the right side of the main river, cross a small stream of most deliciously cool water which joins the original Okement, now a mere thread on the right, then over some dry peat land, past a hollow and flat piece of ground in our front, up over a huge bank of peat, and on for about 50 yards almost due south until the celebrated pool, about which so much has been said and sung, is reached. It is distinctly disappointing. Instead of a pool, nothing but a depression absolutely and entirely free from water lies before us, a depression about 50 yards across which even egg-shells, bottles, and a small cairn with a tin box in it, do not save from being absolutely commonplace. A visitor for the first time says, “Why, I call this place a fraud. To begin with, there’s no pool; and hang it all, a guide book I got hold of said five rivers ran from Cranmere, whereas only one, the West Okement does, and he doesn’t make much of a run of it.” In the face of such a vandal it is, of course, useless to point out that five rivers do actually run from the Cranmere Bog, by which name the mass of spongeland for miles around is known, and that the very wild and weirdness and solemn dreariness of the place has a charm peculiar to itself. We cannot appease our friend, so having written our names in the book begin our homeward march. We do not go direct, as we wish to go round East Mil Tor, so we strike across the wet tableland for about a mile and a half to Huckadon (Ockerton), where the wet grass and sorry wet ground changes for heather and peat. Then we have East Mil Tor before us; the lowland known as Skit Bottom on our right. The afternoon is drawing on, and already crows are passing over the moorland going in country in ones and twos, and as we near the tor the bunnies, or, as the Yankees appropriately call them, “the cotton tails,” scuttle in and out of the rocks. We get a glorious view of the back of Cawsand (Cosdon) and the surrounding country, but do not linger long, and keeping down over the tor to the left, over New Bridge, then keep to a path which lies along the side of the hill to the Sand Pits, leaving Row or Rough Tor (the most western of the three hills in front of us) about 150 yards to the left, then down by the side of Pothanger Farm (presumably Moorgate Farm) wall to the Moor Brook, and then across it into the park, along the road which takes you past Fitz Well on to the station , and from thence home, where we arrived at 6.30, having left home a few minutes before 11 in the morning.

The points of the walk are to Meldon Viaduct, to the Island of Rocks, to Blackator, to the copse, across the south side of Dinger, and on to Cranmere; then over Huckadon to East Mill Tor, New Bridge, to Sand Pits, Moor Gate, and the Park. The time allowed for doing it easily, and allowing moderate time for refreshments and for views, &c., to Meldon Viaduct, 2½ miles, one hour; from thence to the Island of Rocks, 2½ miles, one hour; from thence to Blackator, 1½ miles, half an hour; from thence over the south side of Dinger to Cranmere, 2½ miles, 1½ hours; from Cranmere to East Mill Tor, 3 miles, 1½ hours; from East Mill Tor to home, say 3 miles 1½ hours – distance about 16 miles.”

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor