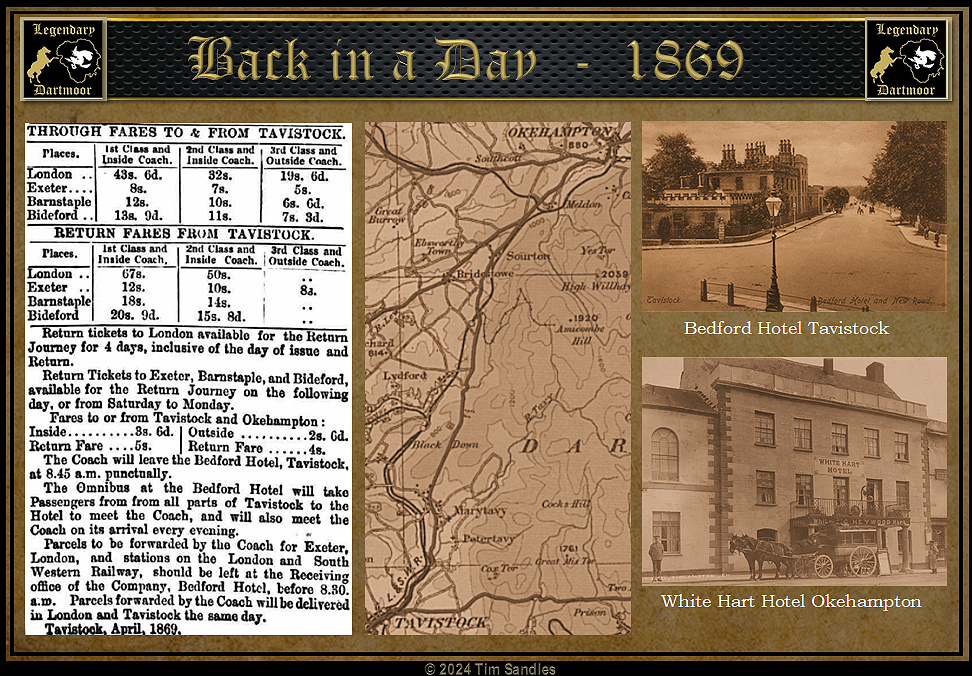

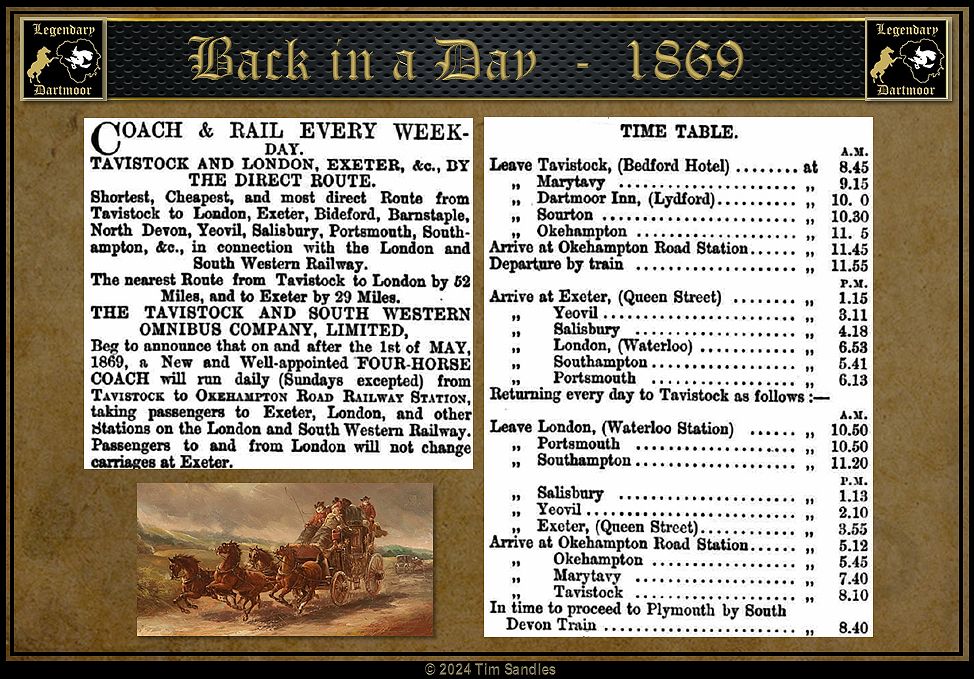

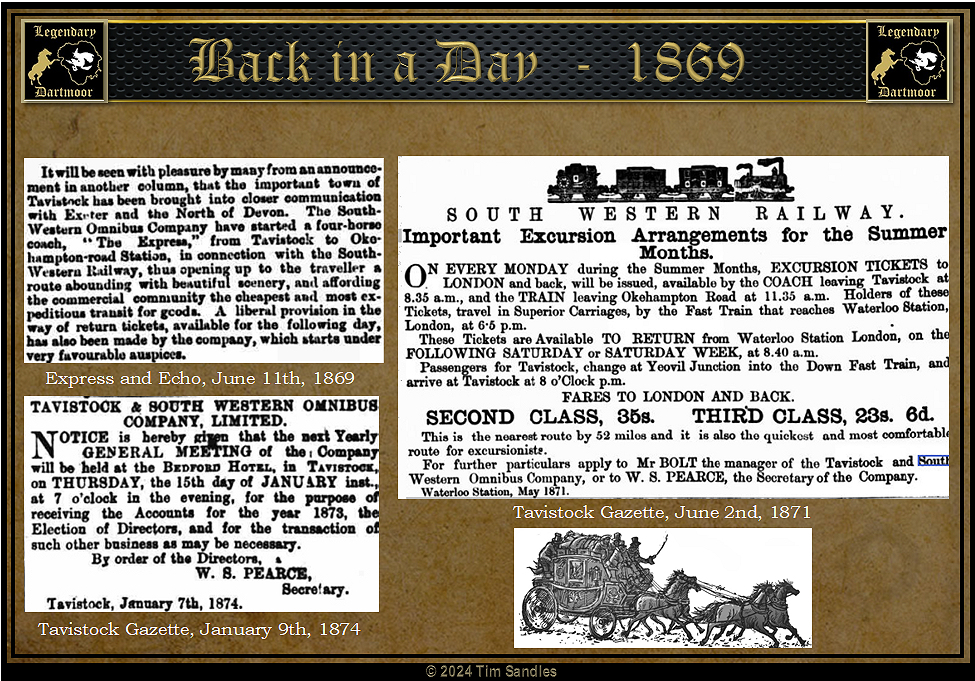

For centuries the only means a passenger had of traveling between Tavistock and Okehampton and beyond was by means of a horse-draw coach. The coming of the railway was the ‘death knell’ for the owners of many of these coach companies, the staging inns, and indeed local hauliers. It was assumed at the time that there was no way horse power could compete both in speed or in comfort with the ‘iron horse’. But in 1869 one company dared to take on the might or the ‘iron road’ by introducing a coach service which ran from Tavistock to Exeter thus enabling a connection with the various rail routes from there. On the 23rd of April 1869 the Tavistock Times published the following announcement, “THE TAVISTOCK AND SOUTH WESTERN OMNIBUS COMPANY LIMITED – Beg to announce that on and after the 1st of May, 1869, a new and well-appointed four horse coach with run daily (Sundays excepted) from Tavistock to Okehampton road railway station, taking passengers to Exeter, London, and other stations on the London and South Western Railway. Passengers to and from London will not change carriages at Exeter.” As can be seen from the image of the original announcement below the company were very much stressing the fact that the service provided the shortest, cheapest, and most direct route from Tavistock to Okehampton. On the inaugural trip a local reporter was invited to ride on the first ever coach of this new service. In his article he was going very much down the nostalgic route by saying that although the rail service was in place many people still desired the old method of transport. The opening paragraph read, “The Time is not long past when the introduction of the iron road to a district was the signal for all the old “stagers,” as they were termed, to find fresh roads for the display of horse flesh or hide their heads for ever beneath the remotest shade of one or other of the hostelries which gave them birth. And as a general thing, the laws which govern this as well as every other branch of trade had to be obeyed. The competition was too sharp; the “iron horse” reigned supreme. This feeling of supremacy, which is ofttimes admired when combined within certain limits, is apt, however, to engender a system of monopoly, highly injurious to the public, and which ultimately tends to the injury of those persisting in its continuance… As such benefactors, the South Western Omnibus Company deserve hearty and substantial support from the public, they having, by means of their communication with the narrow gauge line at Okehampton, conferred a boon which cannot be too highly appreciated. The country through which the coach runs presents great natural attractions, nature having been most lavish in her adornments; this we imagine, will have considerable weight with tourists and men much confined to business, who will thus have an opportunity of viewing the country to the best advantage. Through the courtesy of the directors we were enabled to take the route on the morning of starting, and below we give our impressions of the journey.” Today you can still virtually follow the same route along which is now the A386 road. The distance from Tavistock is about 16 miles and on a good run will take about 25 minutes. Back in 1869 the time taken to travel from the Bedford Hotel in Tavistock to Okehampton railway station was according to the published time table was three hours. This would also include a brief stop at the Dartmoor Inn and a longer halt at Sourton to change the horses. So hop aboard the ‘Express” coach and enjoy the experience…

““Coaching” it is a term but slightly familiar with the rising generation, hence the crowd which gathered in front of the Bedford Hotel, on Saturday morning, the occasion of the starting of the coach to Okehampton Road Station. The morning was truly a May morning. The sub shone joyously; the trees in the old churchyard flung wide their leaf-laden branches to catch the gentle breeze that played around them; the birds were chirping and caroling as if conscious of the return of old “May;” And the strain seemed to be caught up by the flour sleek creature in harness that were pawing and restless, anxious to be on their journey. With such associations as these, we took an outside seat on Saturday, in pleasant anticipation of a drive over the moor. Punctual to the minute our coachy mounted the box and drove off at a rattling pace amidst the kindly cheers of the crowd. Returning the cheers and nods which continue through the streets, we soon leave the town behind, and enter upon some of the most picturesque scenery in the neighbourhood. On out right nestled amongst the trees stands Mount Tavy with its woods and grounds in all the hues of spring, while at its feet the river flows out its winding course. Passing Parkwood, the seat of C. H. Daw, Esq., we cross the Walla brook, just on the point of joining its love, the Tavy. Of the vale through which the Wall runs Tavy Cottage and Hazeldon with their fine command of river, meadow, and woods, are soon left behind us, and we “cross the line” without retorting to any of those barbarous habits with which literature of our boyhood were familiar. It is with a feeling of pity that we look on the cold rigid line of iron rails in view and compare them with the “animated mettle” in front, now beginning to “feel” themselves, and taking us at a rapid pace towards the moor. Cox Tor, with its grey lichen-covered granite boulders, looks grand in the morning sun, as if with sentry’s stealth, she has kept watch on the little villages beneath, whilst the church towers of St. Mary and St. Peter are peeping over the treetops, invoking a passing glance, unwilling that all the praise should be shared by the towering hills above. At the village we are again met by kindly nods and welcomes and wishes of success which is always reciprocated by that peculiar jerk of the elbow, which can only be performed to advantage by one accustomed to handle the “ribbons” (reigns).

A brisk bracing breeze reminds us we are on Black Down, and we give our ancestors credit for once calling something by its proper name. This dull and dreary piece of moorland deserves the name of Black; and we wondered much that such a cheerful bird as the lark should make this wilderness its home. The scenery from the summit, however, causes a reaction of any sombre impressions; a delightful panorama presents themselves to view, cheering and elevating the dullest spirit. Yonder, on the summit of a high tor stands the church named Brent, rich in tradition and lore, and having such an appearance in the distance as to be designated the “cradle of the moor.” Various are the causes assigned for erecting such a building in that wild spot; but the most generally accepted is that of a captain being wrecked at sea, having vowed to his patron saint that he would erect a church to his honour on the first point of land which came into view, should he ever reach the shore. That he did reach land the church is considered sufficient testimony. It is a plain strongly built edifice, and such it need be to stand for hundreds of years considering the storms with which these tors are visited. On its outside wall is a curious headstone, most gorgeously adorned with “cunnynge carved work,” dating about the time when Cromwell, that “chief of men,” with his army of Invincibles, was in the west, purging and purifying the land. While moralising on the past, our steeds have been moving rapidly along, taking us into the entire change of scenery. What was once bleak and barren has yielded to the perseverance of man, and on the other hand rich cultivated fields are yielding their crops in obedience to the great all-governing laws. Cattle and sheep are browsing amidst luxuriant grass, which would be considered very superior on lands far beyond the reaches of Dartmoor’s influences.

Ascending a slightly elevated piece of ground, we come in sight of Lydford, and cannot hep comparing the few scattered houses now struggling as it were for existence, with the time when it was a famous “walled city.” Nothing remains to speak of its former importance but a square building, called the Castle keep, situated on a high mound of earth, forming a conspicuous object for miles around. To the antiquarian this locality affords fine scope for investigation. Ethelred is said to have had a mint here, the coins of which are still in existence; and Julius Caesar honoured the city with a visit on his second invasion of Britain. We reflect on the vicissitudes of cities as we remember that this place was once rated, according to the Domesday Book, on the same equality as London. In the castle stannary courts were held, which had the power of punishing offenders against Stannary laws. The dungeons were such as to give rise to the adage “Lydford Law punished first and tries after.”

We descend a rather abrupt hill to Kitt’s Bridge, where a small stream of water meanders through a picturesque valley, beaming with wildflowers in the greatest profusion. The bed of the stream at this season of the year is almost dry; but when swollen with winter rains and dashing against the boulders which here and there impede the progress, forming mimic cataracts, the sight must be one of great beauty. At such “pinches” as this part of the road presents, the skill of the driver is brought prominently out. To handle four spirited horses is more a science than we anticipated, and we must give our Jehu (old term for coach driver) the honour of added credit to his profession by the skilful and careful manner in which he took us around some rather intricate windings. The Dartmoor Inn, with its trim, white-washed face is soon reached, where for a few moments horses and passengers yield themselves up to a sundry “mouth-washings” as the portly host designates it, to clear any particles of dust which by chance may have become stuck in the throat. We bound along again through a country beautiful in its loneliness. On our right the grand old tors of Sourton look frowning down upon us with ever-changing hues, as the great cloud-shadows are flung along their rocky sides. Nature seems to have supplied the place of art in these regions, the hedges around the fields for miles being generously arrayed with the bloom of furze and heathbell, while the cottages which stud the way, clean though rude, add a brightness to the scene.

At Sourton we change horses and have a few moments to exchange glances with the villagers, who have turned out en masse. Many of the older members of this fraternity remember when Sourton, in their estimation, was an important stopping-place for the four horse equipages from Exeter. But the railway suddenly shut them out, and for a time they might have been considered as almost out of the world. It was with a merry twinkle of the eye that one old gent related to us the impressions of the old four-in-hands that came streaming into the village, with their ponderous loads behind them. “Them waz the times, zur,” said he, “ when us seed a little life, now us scarcely knaws what’s a goin in the world, ‘sept us gaws tu Okington.” What his ideas if “life” were, we were at a loss to discover, and consider the latter part of the remark as slightly tempered irony. We have a peep at the little church, which is famous for nothing in particular but its seclusion, and again mount our seat. The horses are literally “fresh,” and take the road beautifully. There is after all something particularly fascinating in driving through the country. The pull-up of the teams we meet; the wondering looks of the passer-by; the exhilarating air, the companionship of your fellow passengers; and the courteous reply to all enquiries of those familiar with the locality, all combine to pass the time delightfully.

Half an hour’s drive, and the sight of the remains of an old castle, warns us of near approach to Okehampton, and in a few moments we pull up in front of the White Hart, the observed of a host of the populace. Friendly greetings are the order of the day, and as we have a short time to spare we look around and make good use of it. As we pass over the bridge and view the river, we are reminded of poor Carter Foots, who was allowed to drown without a helping hand being stretched to assist him; Tavistock men being held but slightly in the esteem of their Ockington brethren. (This is reference to the one-time animosity between the two towns, more than likely due to jealous competition for recognition.) Being of the same stock, we speculate as to our probable fate, placed in the same position; but the open, smiling, bustling faces of the inhabitants, now in anxious preparation for the vent of the week, the market, assure us there is no lack of benevolence now, whatever feelings characterised their ancestors. In the direction of the castle, a number of villa residences have lately sprung up; and although sharing the same fate as most other towns at the present time, business cannot be classed exactly as “dull.” One tradesman there is considerably in advance of his neighbours, as he announced by means of a coloured placard that he “defies competition!” The church situated about half a mile from the town is comparatively new, the old building erected in 1261, having been destroyed by fire in 1842, it being reduced to ruins in half an hour. The castle remains exhibit in their decay, traces of its former strength and grandeur long passed. Okehampton bore a conspicuous part during the civil wars, it being kept by the king’s army for three weeks; Essex however routed them in one night. During the reign of Edward I, it sent burgesses to Parliament, which continued with but slight intermission until William IV., when it became disenfranchised. There is much in the neighbourhood which cannot fail to be a pleasure to the visitor or tourist, the combination of wood and river, hill, and valley, forming scenery of the most beautiful description. The crock of the whip – though only in admonition – is heard, and we regain or seats for the railway station, which is reached sometime ere the departure of the train. We again alight on terra firma and congratulate our “whip” on the pleasant and successful termination of the first journey and wish him many such trips in the future.” – The Tavistock Gazette, May 7th, 1869.

A similar circumstance arose when the A30 was constructed along with the Okehampton by-pass road which was opened in 1988. Previous to this all traffic had to drive through the town and then via Sticklepath, South Zeal, and Whiddon Down on its way to and from Exeter. This obviously was a great boon to the local businesses and services along the way. The new by-pass meant that all their trade literally by-passed as the traffic sped by taking both travellers and visitors with it.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

A very interesting article, thank you Tim. Do you know how long this coach service ran for?

John