“Sunshine played over the blue hazes and touched the grey summit of Shepherd’s Cross, where the ancient stone stood erect and solitary on the heath. It reared not far distant from rough, broken ground, where Tudor miners have streamed the hillside for tin in Elizabethan days. The relic glimmered with lichens, black and gold and ash colour. Upon its shaft stuck red hairs, where roaming cattle had rubbed themselves. It stood the height of a tall man above the water worn trough at its foot, and the cross was still perfect, with its short, squat arms unbroken, though weathered in all its chamfering by centuries of storm.” – Eden Phillpotts, Orphan Dinah – p.337.

Kenneth Day notes in his book that the above ‘Shepherd’s Cross‘ was not the fictional name for Huntingdon Cross dreamed up by Eden Phillpotts but was in fact a genuine name sometimes used by locals, p.208. I must admit Shepherd’s Cross is a much more rustic and appealing name than Huntingdon Cross and is a pity that somehow it’s been lost in the realms of tradition. As the cross is a Christian symbol it would be interesting to know whether the ‘Shepherd‘ referred to is Jesus or a one-time local sheep herder? If the name pertains to a sheep shepherd was this spot a ‘telling place’ where the sheep were gathered and counted, similar to Horn’s Cross? Alternatively is it a personal name belonging to someone who frequented the area known as Shepherd?

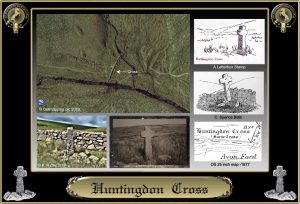

Anyway, It has been argued that possibly Huntingdon or Shepherd’s Cross once served as a marker on the Jobber’s Road which later became the Abbott’s Way. Other authors refute this and suggest that the cross was specifically set up as a boundary marker in the mid 1500s, Brown, p9.

The actual location of the cross is just above a spot known as Lower Huntingdon Corner and is where the Abbott’s Way crosses the river Avon by means of a ford. William Crossing aptly describes the remoteness of the scene in the early 1900s thus: “The only signs of life are the furry inhabitants of the warren, and perchance, a herd of Dartmoor ponies, wild as the country over which they roam, and a few sheep or cattle grazing on the slopes,” p.21. Whilst the cross still retains its remoteness the ‘furry inhabitants of the warren‘ have long gone leaving just the sheep, ponies and cattle.

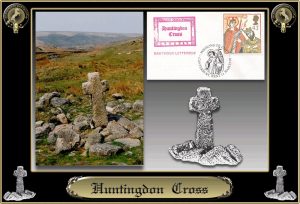

The vital statistics of the Latin style cross are a height of 1.38 metres with a span of 56 centimetres and a shaft circumference of 96 centimetres, Sandles, p.54. In 1557 the cross was pressed into service as a boundary marker for the manor of Brent. Huntingdon Cross was a favourite port of call when the parishioners of Brent beat their bounds. It was here that a ‘substantial’ luncheon would be provided for those attending. Originally there were four such boundary points and Huntingdon Cross is today the sole survivor. There is some debate as to whether or not the cross originally bore an inscription, if so there is no sign of it today. However, one Dr. Oliver recorded in his Monasticon Diocesis Exoniensis that the words ‘Bunda de Brentmore‘ had been inscribed on it. Once again in 1759 it became another boundary point, this time delineating the limits of the Huntingdon Mine. of the Huntingdon Mine, Brewer, p.139.

As Eden Phillpotts noted above the cross has for centuries been used by livestock as a rubbing post which incidentally is the reason why so many of the moorland artefacts get a dark staining on them for the animals natural coat oils. In late 1990 it was a case of one rub too much and the cross broke at ground level, fortunately it was restored and the large boulders placed around its base to deter future itchy beasts. For some odd reason the stone wall was rebuilt just to the north of the cross sometime prior to 2001, on my OS map this has not been recorded but the wall is clearly visible on Google Earth. Apparently the reason for this was to stop livestock wandering onto Duchy lands and by using the river Avon and the Western Wellabrook on either side it forms a barrier.

Although the name ‘Huntingdon‘ attaches itself to many other landscape features in the area it is worth seeing how it came about. There are two suggestions, firstly Gover et. al. considers that in 1481 the nearby warren was recorded as being Huntyndon. The two place-name elements being Huntyn and Don which have mutated from the Old English word hunta meaning hunter and dun meaning hill thus giving the ‘hunter’s hill’ or ‘hill of the hunter’, p.195. Alternatively William Crossing’s option is that the first element has mutated from the word aun meaning water thus giving ‘ the Water Hill?, p.20. The word aun itself has mutated firstly to Aune which in itself has then mutated to Avon giving the modern name of the river.

Any visit to the cross albeit just passing or exploring will be amply rewarded with numerous nearby landscape features ranging form the prehistoric to the modern day. I can particularly recall on one visit having a strange encounter with a group of French youngsters whilst at the cross. Sadly their English was marginally better than my French so communication was achieved by much shouting, pointing and hand gesturing. If I got things right they were heading for Princetown with no map or compass and had become lost. No amount of yelling ‘non’, ‘non, shaking of head or violent hand gestures would deter them from their mission. In this situation the most probable and safest route would be to head up and over Green Hill, pick up the Blacklane and head to Fox Tor then on to Princetown. Sadly I did not know the French word for mire as in Foxtor Mires so I hope that on reaching Foxtor they did not head directly to the first visible sign of human habitation in the form of Whiteworks? On the other hand if I got things wrong and they didn’t want to go to Princetown then there would be an issue. On another occasion one hot summer’s day I was wandering up through the heather from the cross to the Heap of Sinners. For some reason I happened to look down at my feet and to my absolute horror saw a large, orange coloured adder slithering over my boot. No exaggeration it must have been at least three metres long with needle sharp six centimetre fangs dripping with venom or at least that’s how it appeared. In all reality it was around one metre long with mouth firmly closed and possibly, though doubtful, more afraid of me that I was it. The rest of the day was spent watching the ground and not sitting down anywhere.

![]()

Brewer, D. 2002. Dartmoor Boundary Markers. Tiverton: Halsgrove Publishing.

Brown, M. 1998. Dartmoor Field Guide – Vol. 21. Plymouth: The Dartmoor Press.

Crossing, W. 1987. The Ancient Stone Crosses of Dartmoor. Exeter: Devon Books.

Day, K. E. 1981. Eden Phillpotts on Dartmoor. Newton Abbot: David & Charles

Gover, J. E. B., Mawer, A. & Stenton, F. M. 1992 The Place Names of Devon, Nottingham: English Place-Name Society

Phillpotts, E. 1920. Orphan Dinah. London: William Heinemann.

Sandles, T. 1997. A Pilgrimage to Dartmoor’s Crosses. Liverton: Forest Publishing.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

One comment

Pingback: Monday Mashup | Dartmoor Hiking