Here is an account come guide book come survival guide for Dartmoor which was written in 1873. As can be seen somethings never change whilst others give just a glimpse of days long gone by and never to be seen again. Some will say it’s a good thing whilst others like myself can’t help wishing they could have seen what this author saw and experience what events encompassed his days on Dartmoor

“No one can be deemed antiquated with this native land until he has seen the Royal Forest of Dartmoor. Easily accessible from all sides, its extent is not more than a three-days’ walk in any direction, and during that time nit is possible to make a very fair examination of its chief sights by a little judicious consideration beforehand. The following notes are intended to simplify the process. By way of approaching the moor at the most usual point from which pedestrians enter, we will start knapsack on back and staff in hand down the picturesque Fore Street of Exeter, and so over the Exe River up the ridge of hills on its right bank, all of them commanding fine views of the cathedral city of the West.

While plodding up these hills it is worth gaining a general idea of Dartmoor. Devon is celebrated for the mild temper and amiable nature of its inhabitants., and yet it is a peculiarly stony-hearted country. In an artistic point of view this central district of Dartmoor is well described by De La Beche as ” an elevated mass of land, of an irregular form, broken into numerous minor hills, many crowned by groups of picturesque rocks provincially named tore, and, for the most part presenting a wild mixture of heath, bog, rocks and rapid streams.” A better idea, however, will be gained of it by conceiving a vast plain of liquefied quartz, mica, and feldspar, which on slowly cooling has been sank into rolling depressions and every here and there upheaved as lofty eminences through the peaks of which fantastic piles are thrust for wind and weather to play upon, and render still more grotesque. The granite district is, save in the case of these last-mentioned tors, thinly covered with a carpet of heather and furze, the depressions being marshy-peat bogs, impassable in wet weather; few or no trees can face the winds that tear across it in winter, while from its elevations acting as condensers of the Atlantic mists, the climate is, even for the West of England exceptionally damp and rainy. Its borders may be popularly bounded by Oakhampton on the north, Bovey Tracey, Ivy Bridge, and Tavistock at the other cardinal points. Thus Dartmoor may roughly be calculated to extend twenty miles across and twenty-two miles from north to south, and to contain more than 130,000 acres of land. Let us add, that its beacons and tors are the highest elevations south of Calder Idris and Snowdon, Helvellyn and Ingleborough. Cosdon Beacon (1792 feet) was considered the highest point of Dartmoor till De La beche determined Yes Tor to be 2050 feet, and Amicombe Hill to be 2000 feet high.

Eight miles from Exeter the upper waters of the Teign are reached at Dunsford Bridge. There is a roadside hostelry; but the hills close in upon it in such a manner that sunshine cannot strike it during the three winter months. The Teign itself, when in full volume, must present the usual features of a mountain stream; but in that driest of dry summers, 1870, it was shrunk to the dimensions of a mere brook. A philosophical harvest-man informed us in that year that the fish used to be more plentiful than they now are; “It zims to me as how the old uns have got bigger and eaten the little uns.” If this be so, each year anglers ought to provide themselves with stronger tackle. The water, like most moorland streams, is dark, owing to the peat beds through which it finds its way, while its bed is composed here of sheets of granite, there of red and dark yellow pebbles, and at a third place again is nothing more than a heap of boulders, flung together in a confused mass as they were left by the last flood; over and under these the Teign forces its passage, now extending itself into a deep sullen pool, then relaxing into a gentle murmuring thread, and finally leaping over a mimic waterfall to resume the previous variations. Wild scenery of woodland with occasionally lofty banks clothed to the summit with trees, hems it in and renders a ramble along its course delightful to lovers of nature. British camps crown the summit of at least two beetling cliffs for the antiquarian; rabbits and rare butterflies everywhere cross the path; while botanists may discover thickets of Osmunda and the hayfern, and splendid tangles of the ivy-leaved bell-flower. Indeed fern and heather are everywhere, and on every elevated boulder in the stream springs a cluster of the ruddy hempnettle. To an artistic eye these upper waters of the Teign posses rare loveliness, combining all the most beautiful features of English and Scotch scenery. Add to this that at times (as at Clifford Bridge and Fingle Bridge) the stream is spanned by bridges of the most picturesque description, and the granite in its bed piles itself up in faint imitation of the celebrated Horsham Steps near Lustleigh, and very traveller will allow that the banks of the Teign form a worthy introduction to Dartmoor.

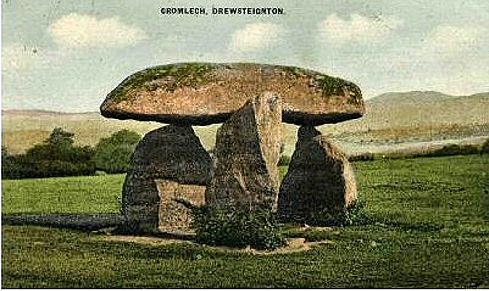

Drewsteignton (i.e., Druids town on the Teign, according to those pre-historic guide books that ye believe in Druids) is a good village to dine in, particularly for hungry mortals. We were regaled upon the largest beefsteak ever seen, very underdone, three inches thick, and served on a huge charger, which it covered. The finest cromlech in Devon (Spinster’s Rock) is to be found near this village. The flat central stone is computed to contain sixteen tons sixteen pounds of granite, and is elevated seven feet from the ground. Probably these structures were used for sacrificial purposes, though Polwhele calls this “the sepulchre of a chief Druid,” and Mr. Chapple (who wrote an elaborate treatise on it) thinks it was “partly designed for sciatherical purposes.”

Leaving behind the three British camps and gazing at Wyddon Park over a vast ravine, at the bottom of which dimly descried from the immense depth, rushes the silver foam of the Teign, one of the finest mountain paths to be found in Devon, conducts the tourist to Chagford. Spite of the attractions of its church and of the old Tudor inn, within whose porch Sidney Godolphin was shot in the Civil War, we shall leave the guide-books to themselves and plunge boldly onto Datmoor proper, which stretches away before it into purple distant rolling tors. Yes Tor and Cosdon Beacon, the two chief elevations of the moor, are rising proudly on our right, and crushing through a detachment of bracken that stands breast-high to oppose our advance on “its ancient solitary reign,” we are at once treading on the grateful heather, whose pollen flies off in white clouds at every step. Soon a bog is avoided, a visit made to a cairn a slight divergence from the path ensues, and lo, we have entered the labyrinth of the West, and lost our clue! Everyone ought to be provided with a compass and Ordnance map who mediates crossing the moor; but many neglect these precautions. The widest plan in such a case is undoubtedly to make for the nearest abode, whether farm-house or miner’s cabin. It was our good fate to fall in with a miner during such misadventure, who dwelt just under Grimspound, and volunteered to guide us there by the shortest path. The breezes blew freshly over the vast expanse before us; bees hummed in the heather, a sheep sprang up startled every now and then before us, or a hawk hung in mid-air suspended over its prey. Never could the moor look so lovely, we think, than on this glorious summer day. Meanwhile the miner amused us by tales of the “old streamers” (i.e. the Phoenicians and early Roman settlers), who took out the tin from the surface “streams” and left him and his fellows the thankless task of excavating for it now. Everywhere he pointed out abandoned mines, where heather and yellow hawkweed were fast resuming their reign, and hiding the unsightly heaps of shale and scoriae accumulated by man’s need or his avarice. But the subject on which he was specially crazed seemed, of all things, to be the bird called a Puffin. “Did you ever see one,sir? I once went to the Isle of Puffins and saw sight of them. They do say there’s never a one of them that can be reared; they never takes a bit of mate after they be caught,” and while resting at his cottage, he fumbled in a drawer and produced with much triumph a child’s book adorned with cuts of birds, and never rested till he had found a puffin. Bidding him farewell, a jocose friend observed, as we breasted the hill leading up to Grimspound, that we had now found ourselves a-puffin! But even the smallest of jokes is well received on a walking tour.

Grimspound is impressive more from the loneliness of its situation, and the associations which the mind conjures up on seeing it, than for anything of itself at the present day. The enclosure, formed of huge granite blocks piled up with a base varying from twenty to six feet, and occupying an area of four acres, is supposed by those antiquarians who yet believe in Druids and their mythical surroundings to have been a colossal temple of the sun. Descending, however to the realms of common sense, and taking the word “pound” in its ordinary ancient meaning the site resolves itself into and enclosure where cattle were protected, either from enemies of the violence of the weather; in fact, it was a walled village, like its analogues found at the present day in the heart of Africa. There are “Hut-Circles” (foundations of early British dwellings) to be traced all around within its circumference; a space is left which may have formed the seat of judicature and political counsel; a spring bubbles up even in the hottest summers on the east side, and opposite it is a small cromlech. Granite is everywhere, grey, barren, sternly grand. The ousels flit by with their white-coloured throats, a few sheep stand in groups around the lonely spot. Taken all in, Grimspound is the most impressive of early British monuments to be found in the country after Stonehenge; it is the English Pompeii.

From these remains over Hamilton Beacon to Widecombe village, with solitude, heather, and granite on all sides, is a pleasant descent. The church tower here is one of the finest in the county, with its crocketed pinnacles and battlements. In the year 1638 an awful tempest broke over the church during service time one Sunday afternoon, killing and wounding many of the congregation, and doing much harm to the fabric. A long and curious account of it may be read in Prince’s Worthies, or on a tablet inside the church, in some simple verses, the composition of the village schoolmaster soon after the accident. The occurrence is still remembered in the village, with awe, and divers legends are told of the foul fiend’s riding up that afternoon on a black horse and being detected by the goodwife of the hostelry as he swallowed some cider, which went hissing down his throat. The old almshouses here, with its continental-looking veranda supported on granite pillars is a very picturesque feature of the village.

Ponsworthy which is the next station on the road to Dartmeet, much resembles an Irish village in its squalor and the abundance of pigs which are seen everywhere, playing with the children, behaving with becoming gravity in the houses with the elders or rioting loose in the road. From here to Two Bridges, a wilder and more barren portion of the moor is entered, a good preparation for the bleakness and monotony of it some six miles farther at Prince Town. Most extensive views are obtained on every point of vantage, wide enough indeed to satisfy the broadest of Churchmen. At Prince Town is a large convict prison, which was originally built in 1805 to hold the French captives of the Peninsular war. Eight miles from any village, with inclement mists sweeping over it from the surrounding naked tors of granite, it cannot be called a cheerful place, nor is the first impression removed on approaching it, and beholding gangs of convicts working on the open moor outside its walls, under the guard of prison officers armed with rifles and fixed bayonets. It is admirably adapted, however, to the corrective purposes it is designed to fulfil; admission is easily occurred by applying to the governor. It presents the unusual features of a large prison, the cells perhaps being somewhat small and the rations somewhat too good and abundant. Rather less than 1000 convicts were incarcerated here on our visit. Occasionally the impulse to escape seizes one when he is at work on the moor, but he is speedily captured for the most part; some few years ago, however, one, favoured by the drifting mists, gave leg-hail to the officers, and escaped, it is supposed, to the Cornish mines, where he has ever since managed to defy detection. We gave the warders due notice that if we ever came to reside under their care, we should take a speedy opportunity of testing our prowess as runners. Anything would be better than durance vile, where as Carrington sings – “still upon the eye, In dread monotony, at morn, noon, eve, Rises the moor, the moor.”

We have now rapidly penetrated in a north-westerly direction through the heart of Dartmoor. This is the route when a tourist will find most convenient, as well as fullest of the typical sights of the moor. These we have only touched cursorily, as a sample of what a pedestrian may find for himself on any part of the moor. Those gifted with an artistic eye must needs be delighted with the cloud scenery, the wild sunsets, the vast purple plains of this solitude; and though no mode of seeing the country is so satisfactory, taken all in all, as walking through it, a great deal of its beauty and many snatches of his odd-world grandeur may be obtained from the top of the coaches which now traverse it every summer. The only drawback to these is the dust. At Merrivale Bridge and several other places, British antiquities occur for the archaeologist; the ecclesiastical Needless to say the ornithologist deems the moor a perfect p architecture, as in the farms and cottages of Dartmoor, most of them built centuries ago, are weathered and lichen-stained, forming admirable objects for the pencil. Many of our rarer British plants are found on the moor and the botanist will find grasses and the cryptogamic families abundantly represented. Needless to say the ornithologist deems the moor a perfect hunting ground; the waders alone that have been taken on it form an exhaustive list of that family of birds in Britain. The larger raptors too have been frequently captured in its savage recesses. In short Dartmoor possesses mental food for all tastes and each one may ride his hobby over it without fear of interruption. A hunt after the sources of the Dart river at Cranmere Pool, where like the Nile, it conceals its fountains, or a walk through the beautifully wooded Holne Chase, presents peculiar features of its own. We have often been minded, with nothing heavier than a fishing rod and a tin of Australian beef, to seize a week of summer weather and ramble over the moor at random, sleeping by night on a couch of heather, by the side of a watch fire. It would be curious to taste the delights of “camping out” with railways but a few hours from most points. With a pony and a small tent such an expedition would be delightful. But whenever and wherever a pedestrian tempts the moor, let him provide himself with a waterproof coat. Rain falls daily during most of the year, and even when it does not rain there is an abundance of treacherous mist. He must also be specially careful of the bogs, “the stables of Dartmoor,” as they are locally called. The stoutest of bachelors might well quail before encountering the alternative of the Dartmoor proverb; ” He that will not happy be, With a pretty girl by the fire, I would he were atop of Dartmoor, Astugged in the mire.”

Lydford Castle and Childe’s Tomb are connected with pleasing poetic legends, while time and space would fail for recounting even a tythe of the superstitious lore of the district. Giant Dart and the leader of the Wisht Hounds still preserve a precarious vitality with the peasants. The Dart itself may yet be addressed in the old lugubrious couplet – “River of Dart, river of Dart, Every year thou claimest a heart. And if no accident occurs in its full torrent, scarcely a winter passes without some benighted wanderer being lost in the snow. If Dartmoor is very lovely in summer, it possesses its stern side, and a few would willingly encounter a December storm on its heights.

This autumn very many will make its acquaintance at the time of the manoeuvres, and the brilliant colours and bustle induced by “wars magnificently stern array,” even in those piping times of peace, will greatly enhance the charms of the moorland scenery. It is devoutly to be hoped that no over-eager officer will lead a troop of Calvary at full charge into a bog, and that even one luckless tourist may not be swallowed up in such an unromantic quag, to cast gloom upon the spectacle. No more suitable ground for learning tactics and campaigning could have been discovered in England, lying as it does so well away from civilzation, and yet so close to it. Its approaches too admit every kind of manoeuvring, and will demand such skill on the part of those who conduct the mimic warfare. It is understood that the whole district has been thoroughly surveyed this spring by engineer officers, so that maps and guide-books in abundance will be published, a result of the campaign which cannot fail to be useful to future tourists. This paper is only intended tom point out briefly the character of the moor and its natural productions, and to remind visitors that it is a corner of England abounding in varied interests. No one, we are assured, will leave it without feeling that he has possessed himself of many pleasant memories to sweeten his working days, and without acknowledging that a trip near home may possibly be found quite as entertaining as a hurried scramble over the Continent, amongst hungry tourists and greedy hotel-keepers. We may add in conclusion that we have not yet heard of Mr. Cook making any arrangements for a week’s trip through Dartmoor.” – The Bradford Observer – August 9th, 1873.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor