“The little granite church upholds

Four pinnacles like holy hands,

A missioner proclaiming God

To ancient unbelieving lands.

Long time it dared the indifferent hills

Childlike, half frightened, all alone,

Lest chink of matin bell offend

The mother of its quarried stone.

Now it is proven and at peace,

Yet may not sleep, remembering

How on the moor above it stand

Stone row and mound and pagan ring“.

L. A. Strong.

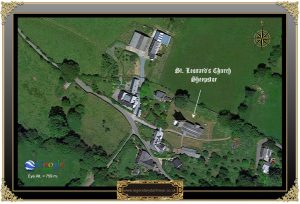

Where on Dartmoor can you find three Rajahs, evidence of bull fighting, a holy well, two ancient granite crosses and a Pua Kumbu? Simple, in and around the little church at Sheepstor. To find all these things it’s best to pick a bright, crisp autumn day when the roads are quite or else you will spend a lot of time in reverse gear shuffling around the narrow lanes. It is a lot easier to park outside the small village and walk down the lane to the church as there are no convenient parking spaces.

The village is snugly tucked in under the shadow of the towering granite outcrops of Sheepstor where for centuries life has passed by unnoticed. Down through the ages the village and parish names have changed more times than a set of traffic lights, the first recorded documentary evidence of a settlement was in the Pipe Rolls of 1168 when it appeared as Sitelestorra, then subsequently in various documents as; Sytelestorre (1242), Schetelestorre (1181), Schitelestor (1219), Schytlestorre (1375), Scitelstor (1244), Skytelestor (1262), Scidistorre (1378), Scitestorr (1408), Shistor (1547), Shepystorr (1574), Shipstor (1607), Shepstor (1620), Shippistor (1691) and then the indignity of Shittestor (1695), (Glover et all, 1992, pp. 238-9). Mike Brown (2007 on-line source) actually lists 36 different presentation of the place-name which he has gathered from various documents. The favoured explanation of the place-name turns out not to be what one might expect as it has nothing to do with sheep. It is suggested that the first element comes from the old Anglo Saxon word – scyttel which means a bolt or bar (Clark Hall, 2004, p.299) and this would refer to the shape of the torre (tor) when seen from certain angles. There is another possibility because another Anglo Saxon word – scytel which means a shuttle and this shape could also be used to describe the tor.

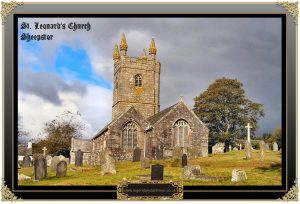

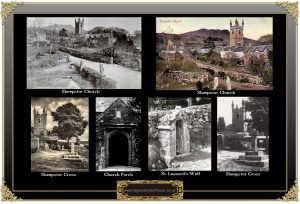

Anyway, enough about place-names this page is supposed to be about the church. In the small church guide available at the church it states that: “for most of its history this church was a chapelry of Bickleigh“. Today there is no evidence of a chapelry although the earliest documentary mention is in 1240. Pevsner must have been having a bad day when he visited the church as his opening remarks were: “The church itself nothing special. Unbuttressed w tower with the polygonal pinnacles of Plympton and Plymouth. The arcade inside of Cornish type with depressed arches” (1952, p.257). The main building was constructed from moorland granite with the window mullions being made from white elvan which was quarried on Roborough Down, it’s thought that the present church dates back to around 1450. Hopefully the following descriptions redresses the balance somewhat: “Sheepstor church is one of those quaint specimens of ancient architecture which are sometimes met with in secluded situations unmarred by the hand of modern improvement. It is of very remote date, and stands immediately under the wild tor which bears the same name as the village. Its pinnacled tower tacitly tells the tale of many a moorland tempest, and other parts of the building bear the marks of the slow, but sure inroads of time. The walls are encrusted with grey and yellow lichens, and young ivies insinuate their tough tendrils into the mouldering cavities. He who is fond of wandering in the cemeteries of country churches will find a rich source of pleasure by lingering in Sheepstor church-yard, when the setting sun of a calm autumnal evening has touched the massy buttresses and crumbled carved work with mellow light. A feeling of religious placidity then pervades every thing round the old building, (H. E. Carrington, p. xxiii). “For hundreds of years Sheepstor was the last human stronghold on the wild fringe of the moor, above it were the stone avenues and circles of a people who had vanished, leaving their township to the rabbits. Its church, forlorn outpost of the new faith, stood beneath a scowling mountain of granite; and the bell sounded so much like the clink of a quarryman’s hammer that the little pinnacled tower may well have trembles lest the mountain should be angry and come to reclaim it stone by stone“, (Megroz, p.87)

Whilst on the subject of clinking bells, the tower at Sheepstor contains a peal of six bells, five of them were cast in 1769 one of which bears the inscription, “I call the quick to church and the dead to grave“. In 1904 the five bells were re-hung and a sixth one added by the actions of the Reverend H. Leigh-Murray, (Breton, p.27). The new bell bore the inscription: “Gloria in excelsis Deo, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis,” – “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to people of good will.” Whilst on a musical note, on the 7th of December 1873 a new organ was officially played for the first time, it was built by a Mr. Hele from Plymouth. A t the time the organ was said to; “a very sweet-toned instrument, and gives thorough satisfaction.” On the inaugural occasion the Rev. W. Daykin noted in his sermon that £20 of the organ’s cost was kindly donated by soldiers who at the time were camped on Ringmoor Down and frequented the church whilst there. In the realms of Dartmoor folklore it was the ropes from these bells which were said to have been tied together and dropped into Crazywell Pool in order to find its true depth and seemingly they weren’t long enough.

Today the church is dedicated to St. Leonard although as Orme (p.199) notes there is no mention of such from 1740 to the 1930’s and it is not until 1940 when the Well of St. Leonard is documented (which is incorrect as Baring-Gould names the well in 1900) and 1983 when St. Leonard’s church is recorded. He considers that it is a possibility that in light of the well evidence the dedication may have been forgotten until recent years. Saint Leonard was a noble at the court of Clovis I and in AD496 was converted to Christianity after which he asked Clovis if he could be permitted to liberate ransomed prisoners. His work soon obtained the release of many prisoners and in return he was offered a bishopric which he declined in favour of a monastic life. Later he moved to the forest of Limoges where he lived as a hermit and continued to pray for the release of prisoners. During this time he saved the life of a Frankish queen who through his prayers was safely taken through a difficult childbirth. Leonard was rewarded for his efforts in the form of some royal lands at Noblac on which he built an abbey where he eventually died in AD559. Tradition would have it that any prisoner who invoked his name would see his chains and shackles snap before their eyes and due to this he became the patron saint of prisoners.

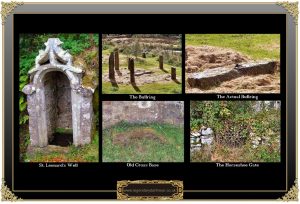

When approaching the church from a westerly direction one is met with a area of paving upon which stands an old granite cross sat neatly on a partly sunken three-stepped pedestal. For those whose boats get floated by crosses this particular one was mentioned by Crossing, (pp. 64 – 65) as in his day (early 1900s) being badly mutilated with both arms missing and serving as a cattle rubbing post in a field at nearby Burrator. The base at this time was lying in a hedge to the east of the churchyard where it seems to have been serving no purpose whatsoever. In 1911 the cross was restored by the Reverend Hugh Breton to commemorate the coronation of King George V which occurred the previous year. The restoration involved the fixing of two new arms and the mounting of the cross on its new pedestal, all the work was carried out by local residents of Sheepstor. There was a dedication ceremony carried out by Reverend Breton on June 22nd which was Coronation Day and the intention of the cross was that open-air services could be held around it. Today the cross shaft stands at 1.62m and has a diameter of 1.1m, the arm-span is 67cm and it stands on a northwest – southeast alignment, on each face is an incised cross, (Sandles, p.90). In his book, ‘Beautiful Dartmoor’, Breton (p.28) tells of how he found a fragment of this cross in the churchyard wall by the stile and had it built into the south-eastern corner of the pedestal. Also, several writers, including Starkey (p. 124) have said how in earlier times this cross has been known as St. Rumon’s Cross or alternatively The Roman Cross but generally this cross is said to be Blackaton Cross on Lee Moor. Baring-Gould (p.229) considers the following: “Above the wood (Burrator) stands Roman’s Cross, probably called after S. Rumon or Ruan, whose body lay at Tavistock. There is another Rumon’s cross on Lee Moor“. So I think we can discount this idea.

The granite paving, step and path was given to the church by Lord Carnock in memory of his wife, Baroness Katherine Carnock and by following this bequest it will lead up to the main churchyard. Saint Leonard’s church is approached through the lychgate in which stands a rare (for Dartmoor) example of a lychstone upon which coffins would be rested whilst waiting to enter the church. This particular lychstone has the initials ‘W E.’ incised into the side of the centre stone which Bayly (p.4) considers to represent Walter Elford who lived at nearby Longstone Manor from between 1576 and 1648.

Above the church sits an enigma, it’s a sculpture that depicts a skull with ears of corn issuing from the empty eye sockets this macabre figure sits squarely upon an hourglass. Above the skull are the words: “UT HORA SIC VITA (As the hour so life passes) and below it: MORS JANUA VITA (Death is the door of life) whilst on the scroll the following appears: “ANIMA REVERTET (the soul will return). There are also the initials J. E. which could represent a John Elford who at one time lived at Langstone Manor. Baring Gould (p.228) also considers that the carved stone was at one time part of a sundial and adds a date of 1640 to the sculpture. The carving was certainly in-situ prior to 1895 because Page (p.280) describes it as: “The most interesting object is a curiously-designed dial plate over the south door… Over this rather gruesome object are the words Anima resurgat;’ at the sides. ‘et hora sic vitae;’ beneath, ‘J E 1640’ and ‘Mors janua vitae’.’ The hand and numerals have disappeared.” Bayly (p.2) contends that skull represents death, the corn; life and the hourglass; the march of time, the whole thing signifying life after death. However, Speth has a different viewpoint: “Over the porch of Sheepstor church in Devon is a skull carved in granite, with ears of corn issuing from the mouth and eyes. This may be the memento of some sacrifice, but I am rather inclined (with Baring-Gould) to look upon it as a survival of the offerings to Woden; the head of the god, and the corn for his horse, (p.234). Whatever it signifies the sculpture at some point has been exposed to the elements (hence the glass cover) which may suggest that it came from a tomb or was a sundial. Incidentally there is no date as to when the glass cover was added but in the early 1900s Crossing mentions its existence (p.66). With the modern vogue for the ‘Green Man‘ or Foliate Head there are those that would classify this sculpture as belonging to that genre. Although the normal run of the mill foliate head is pretty grotesque none of them take on such a macabre appearance as the ‘Foliate Skull’. One theory for this is that they appear after the ravages of the Black Death and therefore tend to portray the grisly side of death. Interestingly enough there is a roof boss in the church of South Tawton on north Dartmoor that depicts a skull with worm-like tendrils spewing from its mouth in a similar vain to the Sheepstor sculpture.

On entering the church the first port of call is the information table, on this one there are two excellent guides, one for the church and the other detailing the family history of the Brooke family. The first impressions of the church are that it’s functional but it is only when one looks around the walls that you realise there is a lot of history contained within. The north wall contains three monuments to the Elford family who have already been mentioned above . The actual memorial reads: “Here lyes John Elforde of Shittor Gent who died 28 Aug 1584. Also Elizabeth Drake first wife of the said John Elforde and late wife of Thomas Drake of Buckland Drake Esq brother and heir of Sir Francis Drake Knight who died 13 Mar 1631. Also Walter Elforde son and heir of the said John Elforde and Elizabeth his wife who died 9 May 1648 aged 72 having married Barbara Elforde died 1656 aged 83. John and Elizabeth Elford…4 sons — John Hugh, Walter, William; 5 daughters — Frances, Joane, Elizabeth, Mary, Ann. As can be seen from the inscription, when the first John Elforde died his wife, Elizabeth, married the brother of Sir Francis Drake who at the time was possibly one of Devon’s most famous sons.

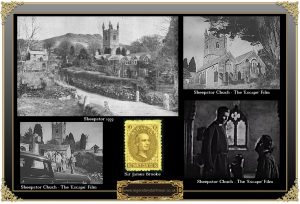

Over the centuries the church has undergone various stages of renovation, and during one of these projects the original rood screen which dated to the early 1500s was mercilessly torn out by a builder from Tavistock. In 1861 the church was, “thoroughly restored”, at a cost of £590, the majority of which was donated by Sir Massey Lopes and Sir James Brooke and his friends – on the left-hand side of the north wall is a tablet listing exactly where the necessary subscriptions came from. The Restoration work was overseen by a Mr. Blatchford of Tavistock and included; two new granite windows, a new roof, the removal of the old gallery and literally all the internal fittings and furniture were brand new. The official opening service of the church took place 2.00 pm on Friday the 12th of April 1861 and was led by the Reverend J. D. Cork and the Reverend J. Hayne. After the service a luncheon was provided for the various dignitaries in the old Priest’s House whilst the villagers and children were also; “regaled in true English style.” In 1874 the Curate of Sheepstor published an appeal in the local press asking for £75 in order to place another small stained-glass window in the north aisle of the church. The window was to be the work of a Mr. Hardiman of Birmingham and was to go alongside another one that was going to be installed.

Having mentioned the sacrilegious vandalism of the rood screen one could be forgiven for thinking I have been on the cider because lo and behold the screen still stands. Well to be exact this is a replica that was copied from a early drawings of the original kept by Sabine Baring-Gould, this allowed Mr. Frederick Bligh-Bond to design the new screen and the work was carried out at the behest of the Reverend Hugh Breton in 1914. There are parts of the original screen incorporated into the modern one and according to Breton (p.40) the total cost was £450 and on completion the screen was dedicated by the Bishop of Exeter on May the 13th which was Eastertide. Whilst talking about restoration, Breton also mentions on March the 3rd the new screen was transported in heavy snow from Exeter across the moor to Sheepstor which I imagine would have been quite an experience.

So, from a snow covered moor it’s time to move on to much warmer climes and it is the south wall which will transport us to Sarawak, the north-western of the two Malaysian states in Borneo. The first thing to grab one’s attention is a rather dust laden and faded ‘carpet’ which hangs on the wall. This is a Pua Kumbu, or a ceremonial blanket, it was a gift to the church from Dr. James Masing, the assistant minister of tourism who presented the blanket as a gift from the people of Sarawak. This took place when he visited the graves of the Brooke family on the 7th of March 1996. The Pua Kumbu acts as a ‘sacred space’ in ceremonies and rituals performed by the Iban tribe and for such events as weddings, births, harvest festivals and at the burial of the dead, in a way its like a portable ‘church’ that holds a great spiritual significance. It is said that the carpet acts as a sort of no-man’s land that mediates between the spirit world and that of the living, The designs of the Pua Kumbu are literally dreamt up by a select group women who have achieved a high degree of spirituality and see the patterns in visions. Also on the same wall are two memorials related to Sarawak, one is for members of the Sarawak Civil Service who died in Japanese prisoner of war camps during WWII and the other is to Sir James Brooke. It may be prudent to explain that the link between Sheepstor and Sarawak is the Brooke family who through Sir James Brooke began the association at nearby Burrator Lodge.

To tell the story of the Brooke’s of Sarawak would take up a website of its own and should anyone be interesting in getting an in depth picture of that story then they could do no worse that to read Pauline Hemery’s book, ‘Emma and the White Rajahs of Dartmoor’. But very briefly, James Brooke was an officer in the East India Company’s service and in 1825 he was badly wounded in Burma and had to resign his commission. In 1838 his father funded him to buy a schooner called’ The Royalist’ in which he sailed to Borneo and arrived in Kuching (Sarawak) in the August of that year. On arrival he was met with a Dayak uprising against the Sultan of Brunei which he and his heavily armed crew managed to quell after a long and perilous struggle. Accordingly on the 24th September 1841 James Brooke was proclaimed Rajah of Sarawak and under his rule the following 6 years saw the land prosper and peacefully grow. In 1847 Brooke returned to England where he was knighted by Queen Victoria, given the freedom of the city of London and presented with Burrator Lodge which was paid for by public subscription. On the 11th of June 1868 the Rajah of Sarawak passed away and was buried in his fine tomb which today sits at the top corner of Sheepstor churchyard. Breton in his book, ‘Beautiful Dartmoor’ (1990, p.33) notes how, “Men, Women and children wept as the remains were laid in the spot the Rajah himself had chosen. ‘He was beloved by all’“. What local writers seem to omit was that there was one slight problem, because of his sexual tendencies, James Brooke, despite having two children (a son Reuben and a possible daughter) was deemed “unmarried and without issue”. Therefore in 1861 he passed the title of Rajah of Sarawak firstly to his sister’s son who James subsequently banished from Sarawak and then passed the title to a nephew – Charles Anthony Johnson Brooke. Upon his death the title was passed to his son, the third and final Rajah – Charles Vyner de Windt Brooke.

The window in the south wall is a memorial window that was given to the church by the Association of the Sarawak Civil Servants. This depicts Saint Stephen, who holds a stone and Saint Leonard who holds a chain and is also the patron saint of prisoners, both representative of their patronage of prisoners. Below these, Christ stoops over a dying man which symbolises the horrors of the Second World War in Sarawak. At the top of the window is the Brooke family coat of arms, on either side of this is a pitcher plant and below the arms is a night hawk moth. Above the crest is a butterfly that was discovered in Sarawak and named after James Brooke – the Papilio Brookiana. The window was designed by Francis W. Skeat and was unveiled amongst others by Bishop Horace who was the former Bishop of Sarawak in the September of 1950. In light of Orme’s comment regarding the fact that there was little mention of the church’s dedication to St. Leonard until recent times and his patronage of prisoners, one does wonder how much the Sarawak prisoners of war are connected to it? Interestingly enough all the early topographical writers of the late 1800s and early 1900s whilst describing the church do not mention the dedication to St. Leonard, this includes; Crossing, Baring-Gould, Page, Rowe (actually states – no dedication) and Worth. In 1928 a meeting of the Plymouth Philatelic Society suggested that as James Brooke was the first person in the Westcountry to have their portrait appear on a postage stamp the Society should adopt it as their emblem.

Just outside the entrance to the porch is a pathway that leads to another stone cross which is placed beside an old stile. But before going charging off down there if you look to the left of the beginning of the path there is a circular stone placed in the foot of the low bank. At first I thought this was an old grave marker similar to those in Lydford churchyard and having not read the guide took a photo just in case. However since reading Worth’s Dartmoor (p.380) it is now clear that the object is in fact an old granite cheese press and he considers because its original design consisted of a cross within a circle somebody has presumably given it a sacred resting place, this by the way was noted in the late 1800s so it has survived quite well.

At the end of the short pathway is the second stone cross to be found at Sheepstor church, today this one stands at 1.74m and has a circumference of 63cm, the arms span across 63cm and have a north – south alignment (Sandles, p.88). The shaft is of an hexagonal design and in the 1800s was simply described as a post (Harrison, p.105). Apart from that very little is known about the cross except a comment from Breton in his book – Beautiful Dartmoor (p.28) where he says the cross had been recently restored, this would have been in 1911.

In the north-eastern corner of the churchyard stands the various tombs of the Brooke family, the most imposing being that of James Brooke which is made from red, polished Aberdeen granite, as if there was a shortage on Dartmoor? The other two Rajah’s tombs are of local granite and Bayly (p.6) tells how the second Rajah’s tomb took 11 horses to draw it down to the churchyard. Not far from the Brooke’s tombs used to be the graves of four German airmen who died when their aircraft crashed near to Burrator Lake. The men were buried in the churchyard on the 19th of May 1941 but their remains were disinterred in 1963 by the War Graves Commission and taken to the German War Cemetery at Stannock Chase, (Redgrave, p.4). Just along from the Brooke tombs the dark, looming outcrops of Sheeps Tor can be seen intrusively tip-toeing over the hedgeline as if they were peeking to see what was going on amongst the gravestones. On a dark day these granite rocks can seem a very dark and brooding contrast to the light-coloured moorstone of the church.

On the outside of the eastern wall of the churchyard is St. Leonard’s Well and really there are three parts to it, Faull (p.71) relates how this came about. The spring that feeds the well is located on land near to where the church now stands and was documented in a deed from 1570. Sometime around 1875 this particular piece of land was purchased to serve as the Glebe from which the parish parson could gain some income. In the early 1900s the parson decided that too many people were crossing his glebe in order to get access to the spring and so action was taken. The water from the spring was piped across the land where it came out in a newly built well-house thus negating the need for anyone to enter the Glebe. The actual materials used to build the well originally were the stone tracery taken from the windows of the church when it was restored in 1850s. Today this means that the ancient water source is the oldest component of the well, the materials from which it’s built come from a later date and its location is from the Victorian period. In 1994 the Dartmoor National Park Authority decided that the well-house was in peril from passing vehicles and so placed two huge granite slabs either side of the structure to act as ‘bumper’ which would deflect any car remiss enough to get too close. Although the well is classified as a ‘Holy Well’ any healing properties belonging to its waters have been lost in the passage of time, although Strong (p.88) does make a vague comment that small children were brought to the well in order to cure: “small diseases”. Nonetheless St. Leonard’s Well is certainly a jewel in the crown of Sheepstor as the constant waters trickle from the spring above.

Just over the wall that stands behind the well is a field that has been landscaped in the fashion of what could only be described as some kind of prehistoric ritual centre, as this is PRIVATE LAND the field is best seen from the south edge of the churchyard. The centre-piece of this field is a small stone circle which is reminiscent of the Bronze Age circles found across the moor. But it is the granite slab that lies in the centre of the circle which is of the greater interest for in it lies the original Sheepstor Bullring. In his book ‘Beautiful Dartmoor’, Breton (p.29) relates the story how in the August of 1908 a local farmer named Amos Shillibeer was ploughing the Vicarage Field when the tip of his plough got caught in a metal ring which made everything come to a juddering holt. This tale was related to Breton some 40 years later and he decided to try and relocate the mystery object along with Amos’s son George and some heavy bar iron. They successfully found the ring which was set into a 5ft long granite block and soon realised that this was the old Bullring. From here, Baring-Gould takes up the story: “In Sheepstor, adjoining the churchyard, is the old bull-ring. The stone peg and the ring are there to the present day. After divine service on Sunday afternoon, a bear, if it could be got, otherwise a bull, was baited there, and the youths of the parish sat on the churchyard wall and enjoyed the sport. All that is of the past, and in the bull-ring has been erected a shed for tea drinking, and the consumption of cake, cream and gossip“, (p.213). I would suggest that obtaining a bear would have been a rare occurrence but there is no question that bulls were baited here, Breton explains how the bull would be tied to the ring and then set upon by bull-dogs, it was known that the women would wear special leather aprons in which they would try to catch any of the dogs that were unfortunate enough to get tossed by the bull. Any of the dogs that the bull managed to kill were supposedly buried underneath the stone pillar. Whilst the baiting was taking part the villagers would, “irreverently”, hold their feastings and festivities amongst the tombstones of the churchyard. Next to the Bull Ring stood the old ale house from which the thirsty spectators could purchase copious quantities of liquid refreshment whilst the baiting was taking place. The ale house once stood where the present-day village hall is located. There is also an unsubstantiated tale that at one time bare-knuckle prize fights also took place at the Bull Ring which would give the bulls a rest if nothing else. During the early 1900s it is noted that an old man-trap which came from the nearby rabbit warren at Ditsworthy was hung from a pole which stood above the Bull Ring.

Whilst on the subject of festivities, Breton (p.100) tells how it was not just the villagers who enjoyed the odd tipple. During the first part of the 1800s one Mr Smith was the visiting vicar of Sheepstor and would turn up every third week to hold divine service. Holy Communion was celebrated three times a year which by 1835 had reduced to once a year. During this period the Parish Expenses showed entries of anything between £1 and £3 a year for wine which at the time was an extraordinary large amount of Christ’s blood for such a small congregation. But Mr Smith was not on the take and tradition has it he was a generous man because he, along with the village elders would after the service sit on an old stone seat (which was where the main cross is today) and drink the wine whilst holding lengthy discussions.

Another quirky little tale that has attached itself to Sheepstor church is the one about the Sunday when the local , non-resident vicar turned up to take the service but was forcefully prevented from going into the pulpit by the clerk. It was matter-of-factly explained that the clerk’s goose had been for the last week sitting on a brood in the pulpit and it would be, “a cruel shame to disturb her“.

In 1947 Sheepstor’s church was one of several locations used in the filming the remake of John Galsworthy’s film ‘Escape’ which starred amongst others Rex Harrison, Peggy Cummins and William Hartnell.

So as can be seen from the length of this page there is a lot to discover in and around Sheepstor church which would make a visit well worth while. But one last thing that I spotted on my visit was an interesting gate at the front of the small house beside the church. Now very overgrown with brimbles, it is actually made from 41 old horseshoes arranged in a star-like design, obviously it’s fairly modern but fast lapsing into a state of decay – shame it took someone a lot of time to make. They say that the small moorland villages and hamlets are timeless places and you can see why when comparing an early postcard of the 1900s and a modern day photo taken from roughly the same spot – timeless Sheepstor where the ages pass silently by. Ooops, nearly forgot, if you are fed up with the Christian aspect of Sheepstor and want to see the more darker side of the place why not take a wander up the tor and visit ‘The Piskie’s Cave‘ where all sorts of weird and wonderful things happen. The Sheepstor villagers of old are well known for their adventures amongst the piskies of the tor.

Baring-Gould, S. 2003 Further Reminiscences 1864 – 1894, Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish.

Baring-Gould, S. 1982 A Book of Dartmoor, Wildwood House, London.

Bayly, E H. 1992 The Parish Church of Saint Leonard, Sheepstor – Church Guide privately printed.

Breton, H. 1990 The Forest of Dartmoor, Forest Publishing, Liverton.

Breton, H. 1990 Beautiful Dartmoor, Forest Publishing, Liverton.

Carrington, H. E. (ed.) 1832 The Collected Poems of N. T. Carrington, Longman and Co, London.

Crossing, W. 1987 The Ancient Stone Crosses of Dartmoor, Devon Books, Exeter.

Faull, T. 2004 Secrets of the Hidden Source, Halsgrove Publishing, Tiverton.

Gover, J. E. B., et. al. 1992 The Place Names of Devon, English Place-Name Society, Nottingham.

Harrison, B. 2001 Dartmoor Stone Crosses, Halsgrove Publishing, Tiverton.

Megroz, R. L. (ed.) 1969 Five Poets – L. A. Strong, Ayer Publishing, Manchester (U.S.A.)

Ormer, N. 1996 English Church Dedications, Exeter University Press, Exeter.

Page, J. Ll. W. 1895 An Exploration of Dartmoor, Seeley & Co., London.

Pevsner, N. 1952 The Buildings of England – South Devon, Penguin Books, Middlesex.

Redgrave, B. 1989 Sheepstor, The Dartmoor Magazine No. 16, Quay Publications, Brixham.

Rowe, S. 1985 A Perambulation of Dartmoor, Devon Books, Exeter.

Sandles, T. 1997 A Pilgrimage to Dartmoor’s Crosses, Forest Publishing, Liverton.

Speth, G. W. 1996 Builder’s Rites and Ceremonies, Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish.

Starkey, F. H. 1989 Dartmoor Crosses, F. Starkey, Exeter.

Worth, R. H. 1988 Worth’s Dartmoor, David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

Further Reading.

Hemery, P. 2001 Emma and the White Rajahs of Dartmoor, Halsgrove Publishing, Tiverton.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Wonderfully detailed information about the church. We are searching for information about our ancestor who is buried there in the graveyard, Douglas Hanford Schneider. He is my Great Grandfather and while we have lovely and lively photos of him, we do not know much about his relationship to Sheepstor and the church. If there is anything anyone there might refer us to for information, the family here would be most grateful. With hope and grace, we will one day visit ourselves and enjoy the beauty of Sheepstor ourselves.

Excellent article, although the German aircrew were re-buried in the Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery not Stannock. We will revisit the church soon using this article as a guide.