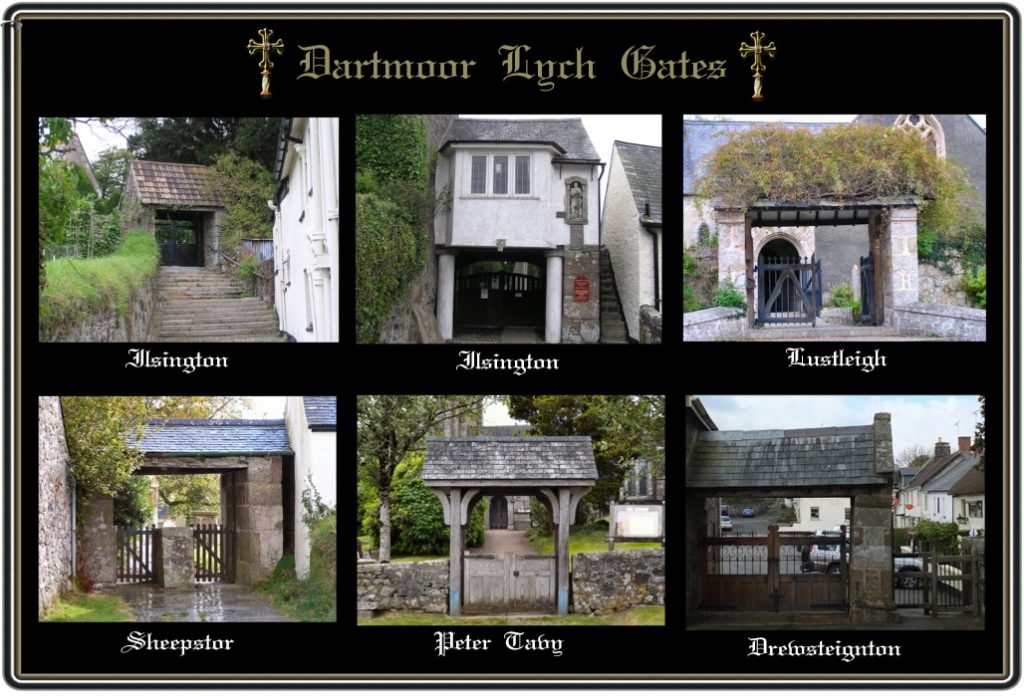

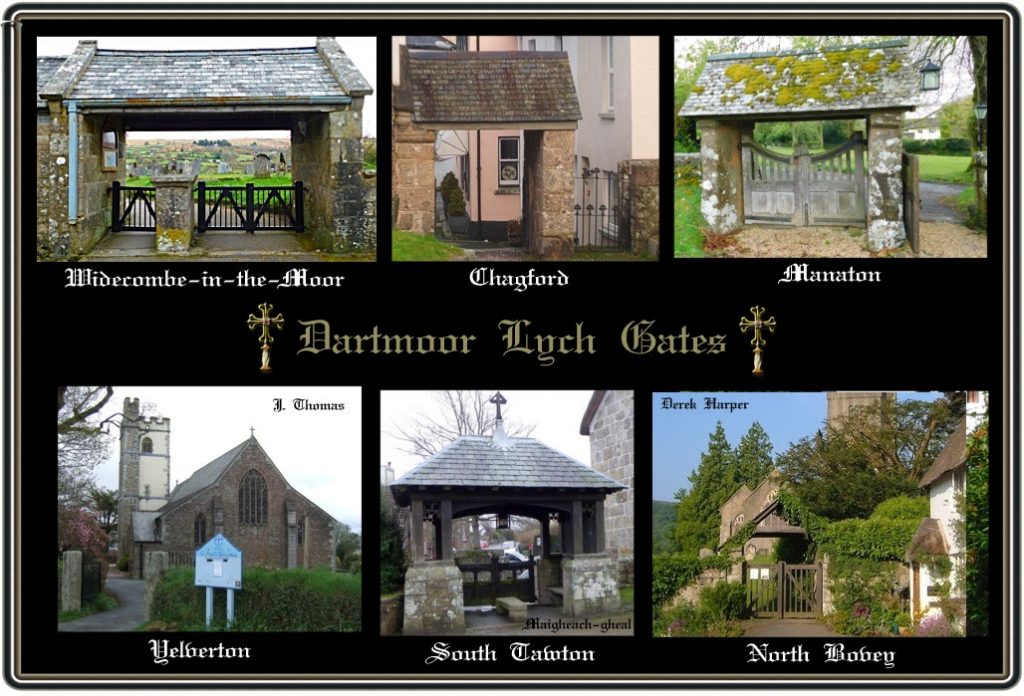

Many of the Dartmoor churches have lychgates of varying architectural merit, design and ages. The actual name is said to have derived from the old English word ‘lic‘ meaning body or corpse as also can be found in Dartmoor’s Lych Way (corpse road). In some parts of Devon these structures are also known as ‘Trim Trams’ which is said to be a corruption of the phrase ‘Trim Train‘. The thinking behind this being that it was at the Lychgate where efforts were made to ensure the coffin was tidied up (The Trim) by the funeral party (The Train) as they awaited the arrival of the priest etc. It has been said that Lychgates date back to the post-reformation days but there are certainly earlier examples some going back as far as the 1400s. In general Lychgates consist of a roofed porch supported by upright posts beneath which is a gate, some of the roofs were thatched, or with wooden or clay tiles. Some Lychgates also included a Lychstone which was a flat stone slab on which the corpse of coffin was laid. As can be seen from the photos below Dartmoor has a variety of Lychgates, some with Lychstones and some without. In the case of St. Michael’s church at Ilsington this can boast not one but two Lychgates. The one located on the west side of the church has a room above it which once acted as the schoolroom. On the 17th of September 1639 whilst lesson were being taught the building collapsed. Several boys were injured, one lost his life and others escaped with minor injuries. It transpired that a heavy rainfall led to the structure and the adjoining building becoming unsafe – for more on the sad event see HERE.

In the pre-hospital days when most moor folk died at home the corpse would have to be transported to the local church for burial. If nearby this was usually by means of the church bier which basically is a platform on wheels. Should the deceased home be in the remoter parts of Dartmoor then it involved a trek along the Lych Path or one of the other church paths. In such cases the corpse would be transported by pony, cart or if not too far distant from the church a bier. Protocol states that the deceased must be led into church by the officiating priest who in some cases would be waiting and if not until his arrival. Should the Dartmoor weather decide to mark the occasion with wet and inclement conditions then the Lychgate provided a modicum of shelter for the funeral party whilst they waited. Where there was a Lychstone then the coffin/corpse would be rested on that. Once the priest arrived he would then bless the coffin/corpse by sprinkling holy water on it and reading the first part of the burial ceremony before entering the church. Over the centuries corpses have arrived at the Lychgate in various ways, at one time it was normal practice to simply wrap the deceased in a shroud which then transitioned into wooden coffins. In 1875 the Tavistock Gazette published a letter written by the a member of the College of Surgeons – W. H. Flower. He was advocating that the use of coffins for burying the dead should be discontinued and things should revert back to what he described as a wicker shroud embellished with flowers and herbs. His reasoning being that a wooden coffin prolonged the process of decomposition and was not the most sanitary solution to burying the dead.

In may cases the Lychgates were built and funded in memory of some departed soul from the community and usually marked by a discrete brass plaque to that effect. Others have been constructed or replaced older ones and acted as war memorials. It must be remembered that Lychgates were/are not intended to be entrances to the churchyard but as an entry point for the deceased. Indeed there was a belief that a bride should never enter the churchyard by the lychgate or else her bridegroom will die before the year is out. It was also thought that the spirit of the deceased who passed through the Lychgate would be in a kind of limbo in the churchyard until the time that another deceased person was carried through the Lychgate. Although not so much a problem these days at one time one could often find that the gates to the Lychgate were locked, the only reason being that it wasn’t unheard of for moorland cattle and ponies to pass through the gate into the churchyard.

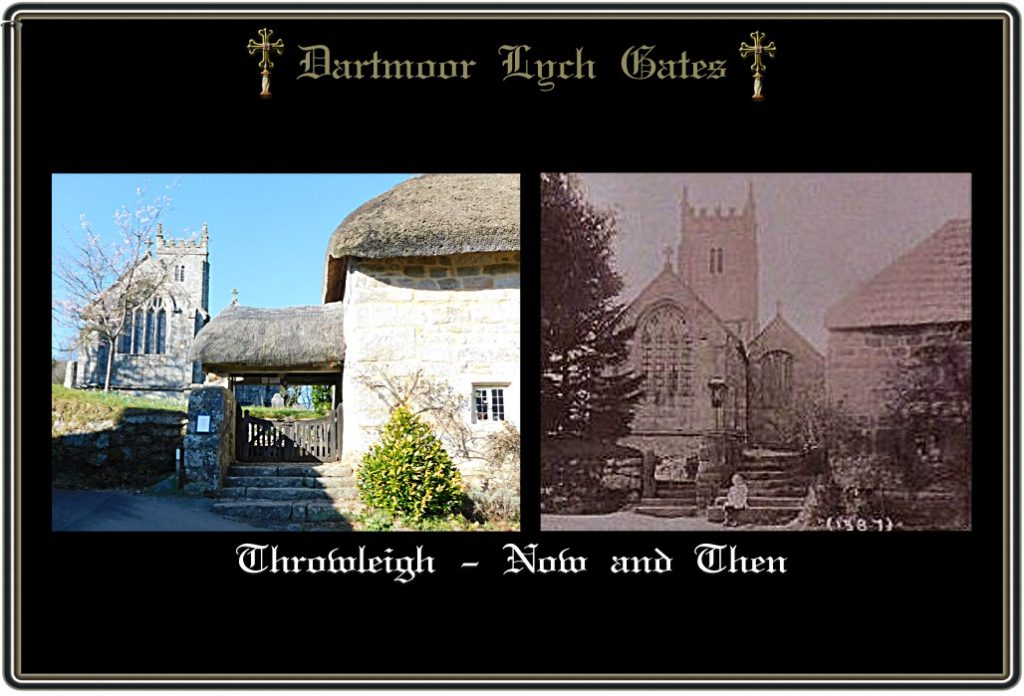

As noted above in some cases the Lychgates date back hundreds of years and it goes without saying that time and the Dartmoor climate slowly leads to disrepair. I would imagine that any church that sported a dilapidated Lychgate would be a great embarrassment to the incumbent and their parishioners due to it conspicuous location. The Lychgate at Throwleigh church being such an example which needed replacing (see photo above). It was said that the previous Lychgate had been demolished at the behest of the then incumbent some eighty years past. His reason being that local lads and lassies used it as a courting place and in doing so made at times an irreverent and raucous din. To that effect in the October of 1936 a brand new Lychgate was opened for business at a dedication ceremony lead by the Bishop of Crediton. It had been the wish of the previous Reverend that such a project should be undertaken. For some odd reason although the wood for building the structure had been procured it sat in the tithe barn for over 20 years? Then the Reverend died and some years later the project was taken up by his son who was the Reverend at Manaton. Finally by means of a subscription the parishioners and friends of the late Reverend raised enough money for construction to go ahead. The gate and porch were designed by a London architect by the name of Sir Charles Nicholson and the actual construction was carried out by local carpenters and thatchers. In the September of 1937 Roborough church also acquired a new Lychgate, this one comprised of massive English oak gates and posts fashioned from wood taken from nearby Ten Oaks Wood with a slate roof and the stone pillars recycled from the former structure.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor