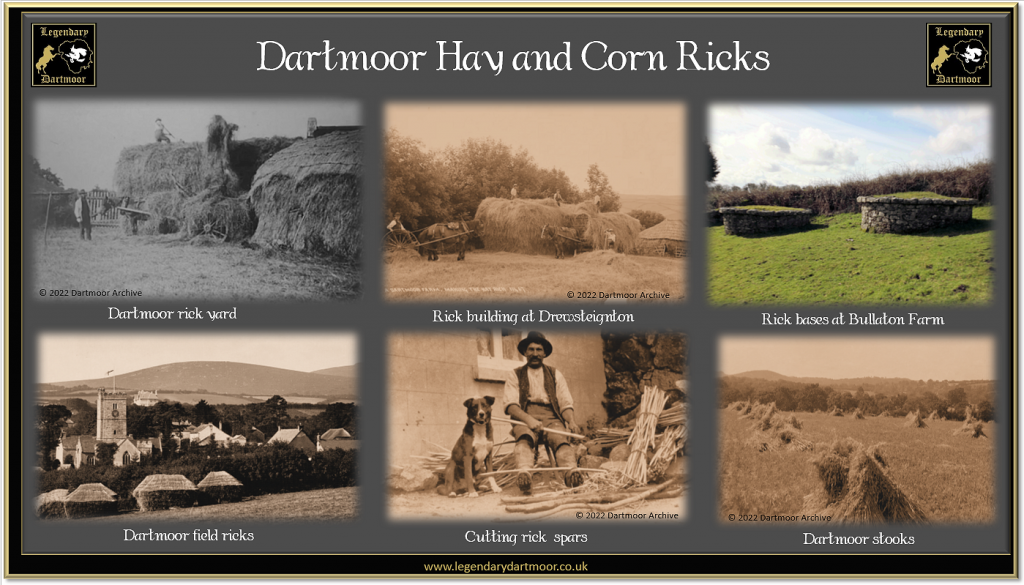

A vital part of any harvest on Dartmoor was storing the crop until it was needed for processing or feed and bedding. Due to the small size of many farmsteads it was not possible in the barns and linhays so the answer was to build ‘ricks’. Numerous crops would be stored this way at various locations in and around the farm such as corn, hay, furze, faggots and even peas. When cut and dried the hay would be carted back and ‘ricked’ and in the case of corn it would be made into field stooks or sheaves (see below) to dry and then made into in ricks which were located in the rickyard, known locally as the “Mowhay” or in the fields. In some cases the rick would be built on purpose-built rickstands such as the two granite ones still visible at Bullaton farm (see below). Some other ricks would simply be built on level ground, either in the field or in the rickyard at the farm. On Dartmoor such ricks may have stood on a platform of furze, gorse or faggots which was in plentiful supply. The idea of the rickstands was to allow the air to circulate which helped prevent the crop from getting damp and to prevent vermin from entering. Very occasionally some farmers would use mushroom shaped staddle stones which again helped air the crop and by its shape help stop vermin from getting into the crop. On Dartmoor there are still examples of rectangular, upright granite blocks which served similar purposes. Once the rick had been constructed it was then thatched with straw or reed and in later years corrugated iron sheets. If you look at any old farm sales notices many will state that there are various ricks up for auction (as can be seen below). If the farm was not purchased ‘lock, stock and barrel’ then it was the purchasers responsibility to remove them which could be a problem. It was not unusual to see court cases where the vendor or new owner/tenant was suing the purchaser for not removing ricks after the sale. Unfortunately, once built the ricks were subject to several problems and perils which could result in the loss of the harvest.

Rick Building.

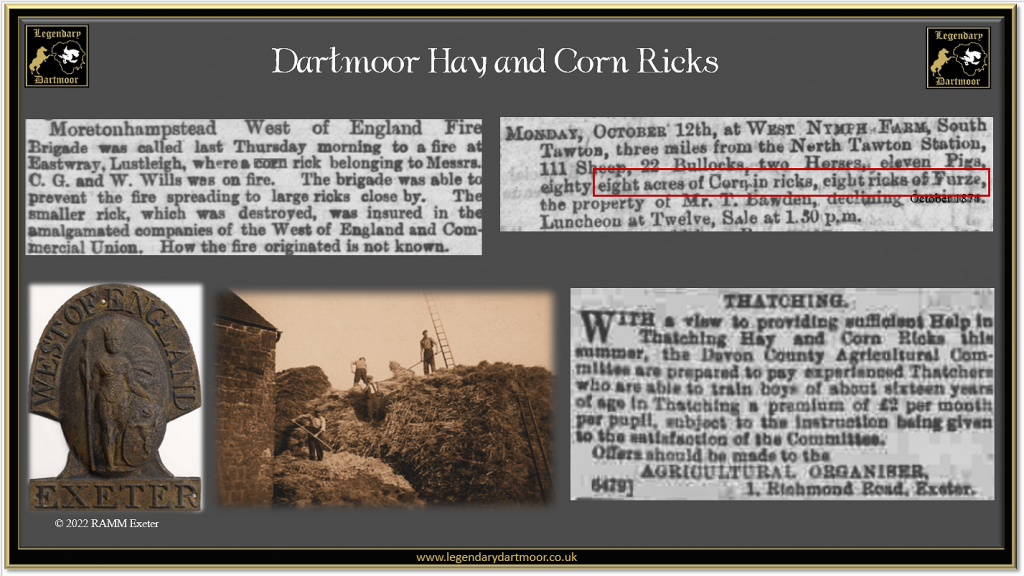

For obvious reasons every structure needs a roof to make it watertight and the same applied to corn and hay ricks. It became standard practice on most farms to thatch the ricks but even this was not straightforward. The original idea of using straw to thatch a rick came about because in the early days it was a cheap and of little value plus the fact other alternatives were not available. But if there were no workers who knew how to thatch then this was an issue. In 1892 it was widely reported that there was a dire shortage of thatchers in Devon and in many cases despite the ricks being built it was several days before a thatcher could roof them. At the end of the First World War in 1918 many men who were able to thatch a rick were either in service, deceased or injured. To help overcome the shortage the Devon County Agricultural Committee were offering to pay any experienced thatchers to train boys of about 16 years of age £2 a month per pupil subject to the training being of the committee’s satisfaction.

However, another solution was the use of corrugated iron ‘slabs’ were available. They were portable and re-usable and easy to erect, it also meant that there was no need for labourers to be able the thatch ricks which in some cases was a great advantage to the farmer. On the downside, unlike straw and reed they were not a cheap or free by product and had to be purchased. Around this time many agricultural societies were advocating the building of ‘Dutch Barns’. These were strongly framed roofs covered with slate or tile and supported by sturdy wooden or granite posts and always oblong in shape. The main disadvantages of this type of structure was that they could never be completely filled due to settling. This meant there was a gap between the top of the crop and the roof which led to the layer nearest the top got spoiled and also dust could blow in and settle.

Weather

In the December of 1836 a mighty hurricane blasted across Devonshire and it was reported that; “hay ricks and corn ricks few about like feathers.” This was by no means a singular event as over the coming years many more moorland ricks were destroyed by strong winds. Even if only the thatch was lost there was every chance that the underlying crop would be spoiled, especially if the storms were accompanied by heavy rainfall. In 1893 numerous corn and hay ricks were completely destroyed when a gale blasted over the Widecombe-in-the-Moor area. The another issue with wind where ricks were stacked close to each other was that if a fire ever broke out sparks could be blown from rick to rick thus causing even grater damaged if not extinguished in time.

Wet conditions were always a headache to the farmer where ricks were concerned from both the spoliation of damp grain and because damp hay and straw was liable to spontaneous combustion in a confined space. There could also be headaches if ricks that had already been constructed during very hot weather were then subjected to periods of heavy rain which again would cause these issues. In many cases it mean that the ricks had to be dismantled and the crops lost.

Lightening or as it was once referred to, “electric fluid” was another concern as will be seen later, could often ignite a corn or hay rick fire with very little warning.

Fire

Probably the biggest threat to a farmer’s rick was that of fire either by an act of nature such as a lightening strike or by a deliberate act of arson. Should a fire ever break out then it could mean a huge loss both in economical and management terms as the crop could not be easily replaced. As the contents of a rick were a valuable commodity many farmers would insure the ricks with various insurance companies of the time. In 1895a rick was destroyed by fire at Eastwray near Lustleigh and this loss was covered by the West of England and Commercial Union. As can be seen below, at onetime some insurance companies issued metal plaques (see below) which would be mounted around the farm and even on the ricks.

In 1855 the secretary to the Devonshire County Fire Office suggested to “Forbid the use of Lucifers (matches), and the practice of smoking in or near rick yards. Ricks to be placed in a single line, and as far from one another as conveniently possible. Hay ricks and corn ricks to be placed alternatively. Rick-yards to be clear of all loose straw. A pond to be provided close to the rick-yard. The steam threshing machine to be always placed to leeward of the rick, and as far from it as may be; the loose straw to be removed continually from it and two or three pails full of water provided close to the ash pan which should always be full of water.” In 1890 the Superintendent of the West of England’s Insurance Company’s Fire Service reported that in the Newton Abbot area from 1884 to 1889 there had been 45 fires in the neighbourhood, these included house thatch and rick fires all occurring six to eight miles from the town

In 1869 a corn rick and two hay ricks at Rushford Barton, Chagford, were found to be on fire. Mr. Nichols of Sandy Park saw a man at the ricks when they caught alight at 4.00 am. But he ran away and the police were in pursuit of him. There were always tramps and vagrants roaming Dartmoor and a hay or corn rick would provide a warm and comfortable shelter for the night. In 1890 William Towill appeared at Tavistock Magistrate Court charged with vagrancy. A police constable found him asleep under a corn rick with a pipe in his mouth which clearly was a fire hazard – sentenced to one month’s hard labour. There were other instances of tramps etc lighting fires near ricks to cook their meals which again led to disastrous fires.

In 1928 fire broke out in two ricks of oats and a rick of barley were totally destroyed in a fire at Charford Farm near South Brent. At the time these crops were the harvest from fifteen acres and valued at £200. These ricks were situated in a roadside field which again highlighted another danger, being so accessible exposed them to arson or even a lighted cigarette being tossed over a hedge.

Other fire problems were caused both by vagrants, gypsies and other travellers whom often camped or slept near or in them. In the March of 1848 one William Smith, an 18 year old vagrant, appeared at the Lent Assizes was indicted with setting fire to a rick of barley at Soldridge Farm, Bovey Tracy. In a statement Smith stated that he came from Hertfordshire and had been traveling around the country for three years. On the occasion of the fire he had visited the farm begging for charity which was denied him. He the went into the field with the rick and dropped a match in it. Once the flames appeared he then agitated the flames until they completely took hold of the rick. Finally he added that; “I did it for envy, and because they would not give me anything.” – found guilty and sentenced to 12 months’ hard labour. In the October of 1906 there was a corn rick fire at Gatehouse Farm near Peter Tavy. There was no nearby water supply so there was no way of extinguishing the flames. Whilst burning the local P.C. noticed an indentation in the rick and returned the following day to investigate. He noticed a gap in the field hedge which suggested someone had entered the field. On searching through the rick’s ashes he found fragments of human bones although no one in the locality had been reported missing. It was therefore assumed, although never proven, that a tramp had crawled into the rick for shelter and lit a cigarette thus catching the rick alight and died from either suffocation or severe burns.

Another fire hazard to ricks was surprisingly enough – children. There were several assize court cases around the Dartmoor area where young children, normally boys were charged with firing a rick by playing with matches (lucifers).

During the Second World War there was a danger of enemy bombs setting fire to corn ricks and crops. Although Dartmoor was at less risk than many areas it was not unknown for enemy aircraft to ditch their loads for one reason or another. Therefore, in 1941 the Ministry of Agriculture issued the following guide lines; “Ricks must not be too big. They must be well separated and not concentrated in stockyards. If on stubble they should be surrounded by a wide ploughed strip forming a firebreak… Water carts should be kept filled near ricks and crops. Firewatchers should be organised for day and night lookouts.”

Vermin.

The biggest problem with any rick is that it provided a cosy winter shelter for rats and mice. It was not unknown for a large rick to house hundreds of them which was always a nightmare for the farmers. It was not unknown for moorland farmers to go to the ricks on moonlit nights armed with a long pole and a terrier. The pole would be thrust into the rick which caused the rodents to bolt out into the awaiting jaws of the dog. Some men made a living by dint of their rat-catcher dogs who would visit the ricks, eject the rats and mice from the stacks straight into the jaws of their eager canines. The was one famous dog who worked some of the moorland farms called Bob, his record for one day was 68 large rats and 320 mice. Ferrets were also used to great effect from eliminating vermin from corn ricks. In 1857 it was possible to purchase for around £3; “A set of cast-iron pillars are so formed that an animal ascending to the top finds himself completely at bay, being covered with an impenetrable dome. With these pillars a set of iron clips are supplied, by means of which a farmer may readily construct a stack frame from any waste timbers found on the farm.”

Throughout the early 1900s there were growing concerns about the huge increase in the number of rat infestations. When living in ricks they not only destroyed valuable crops but almost travelled into nearby homes and gardens. As it was vital that farmers made their ricks rat proof, especially by means of thatching it was an offence. A number of farmers on the edge of the Moor found themselves in court charged by the local Food Controller under the 1914 Defence of the Realm Act with if found guilty hefty fines for each rick. Such was the extent of the infestations that Devon’s Agricultural Committee were appointing rat catchers and distributing poison to local farmers via the local police. In 1919 a farmer near Newton Abbot had offered to supply three men and a boy to go around local farms administering the poison. The only condition was that the council paid their wages, six pounds a week, and provided the poison. It was also decided to divide the cdounty into blocks of 20,000 acres. Each area would have an official rat catcher and over the entire county 80 experienced men to assist them.

During any wartime the production of any food resources is vital and in 1941 the Ministry of Agriculture made an order requiring that; “any rick of corn before being threshed shall be surrounded by a fence of material that is impenetrable by rats. This fence must be placed at a distance of no less that 6ft from the rick, so that any rats escaping from the rick itself may be destroyed inside the fence. Where the foundation of the rick consists of faggots, brushwood, gorse or other material which is likely to afford cover or protection of rats, such material shall be broken up when the rick had been threshed, so as to dislodge any rats therein.”

Although not classed as vermin poultry could also cause a great deal of damage to corn ricks. At Ashburton’s Magistrates Court in 1842 a Mr. Bradridge became tenant of a Mr. Bickford’s estate. At the time the tenancy was drawn up it was agreed that Mr. Bickford’s poultry could run on certain fields “unmolested”. It soon became apparent that the birds were causing a great deal of damage to Bradridge;’s corn ricks and so he wrote a letter of complaint which fell on deaf ears. As a result Bradridge shot three of the birds and as a result was summoned to the court – as a result he was found liable for the loss and fined 6s. for the value of the birds and 14s. expenses. It was the corn ricks located in the rickyards close to the farm that were often damaged by the domestic geese, ducks, and other fowl as these normally roamed the open farmyard

Another issue although not the vermin’s actual fault on game estates was that of poachers. As game birds such as pheasant and partridges and rabbits often frequented corn ricks and they provided an ideal opportunity for poachers to set their snares and wire traps. Numerous men appeared at local magistrates’ courts charged with “trespassing in the pursuit of game.” As many of the magistrates were themselves owners of game estates the poachers rarely received any leniency.

Perils and Miscellanea.

Due to the height and weights involved with ricks there always were numerous risks to life and limb for those working on them, for instance, “Two large ricks of new hay on Down Estate, Ashburton, were late on Tuesday night discovered to be on fire, supposed to have been caused by being saved too quickly. James Bowden, a married man and father of several children, was engaged up to the middle of the day yesterday in putting out the smouldering ricks, when he fell of a hedge adjacent and broke his leg. Bowden was removed the Ashburton Cottage Hospital. As an aside on the same day on the same farm – “John Milton, a young man who assisted to put out the fire, afterwards going into the house of Mr. Pitts to supper, fell over some steps and broke his leg. He was removed to the Ashburton Cottage Hospital early yesterday morning.” – The Exeter & Plymouth Gazette, August 27th, 1885.

A warning issued in 1872 advised that during a thunderstorm a corn or hay rick was not the best place to take shelter, it stated that “many” people had been killed whilst doing so. This was due to the fact that when dry a rick was a worse conductor than the human body. This meant that the ‘electrical fluid’ would pass through the rick to a human body and then into the ground with obvious consequences. Ricks that had been badly constructed also could be dangerous, especially when the corn was being taken out to thresh. There were some fatal cases when the entire rick collapsed on top of the workers and due to the weight they died before being extracted. Another common injury and in some cases death was falling from the rick whilst pitching sheaves from a waggon to the stack. When horse drawn waggons were used it was vital the horse remained still whilst unloading was taking place because should it suddenly moved it was possible for the pitcher to lose his balance and fall off. In 1906 a man was killed in such a manner at West Venn farm on the edge of Dartmoor whilst standing on top of high load of corn sheaves – his neck was broken in the fall.

Theft of unthreshed corn stolen from the ricks was another headache farmers had to contend with. In 1880 a hawker was apprehended at Ashburton for committing such a crime. He along with two others had parked their caravans near some ricks overnight. The next day the farmer discovered that one ricks had been pulled apart and a large quantity of wheat corn stolen. he followed a trail of corn to the camp and saw some horses eating it. He called the local P.C. but by the time they got to the camp the hawkers had gone. They were soon tracked down and on searching one of the caravans found the rest of the stolen corn. – found guilty and fined 2s.

In the November of 1881 a prisoner named Scott was working in an outdoor gang from Dartmoor prison during a thick fog. They were repairing a boundary wall near the gas works when he managed to escape through a door of an adjoining building. A search party of warders, police and locals was soon sent out but for most of the day could find no sign of him. However, late in the day a young boy saw a man hide himself in a hay rick at Blackdown. He immediately fetched the local P.C. from Mary Tavy who along with the lad went to the rick and apprehended the prisoner. On capture Scott remarked, “I did not expect to see you.”

At many of the Devonshire ploughing matches and Agricultural Society shows there would always be rick thatching and spar making competitions which were always fiercely competitive events. If the winners were employees this also gave the respective farmers some degree of pride. If they were thatchers in their own right then this put them in high demand at harvest time. Quite often these skilled thatchers or rick builders would be asked to make miniature corn ricks to place in a church or chapel’s as part of their harvest festivals. Although described as “miniature” in some cases they were quite large, there was one occasion where a rather short vicar was unable to see over the rick it was that large.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor