“And near hereto’s the Gubbins’ cave;

A people that no knowledge have

Of law, of God, or men;

Whom Caesar never yet subdued,

Who’ve lawless liv’d; of manners rude;

All savage in their den.

By whom, if any pass that way,

He dares not the least time to stay,

For presently they howl;

Upon which signal they do muster

Their naked forces in a cluster

Led forth by Roger Rowle.“

William Browne – extract from: A Lydford Journey 1644

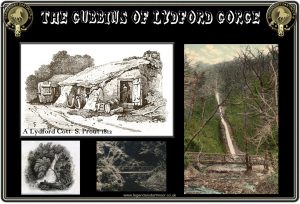

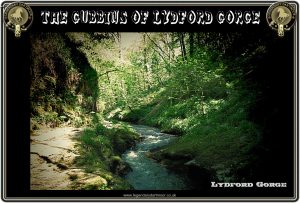

In the sixteenth century a notorious gang of outlaws lived near Lydford, some say their lair was in the gorge. They were led by one Roger Rowle and were the scourge of the area, notorious for stealing sheep on the moor. Rowle was said to have been the ‘Robin Hood of Dartmoor’ and at the village end of Lydford Gorge is a pool called ‘Rowles Pool’. It is his story that is told by Charles Kingsley, in his book – Westward Ho. In the book, Kingsley gives some idea of what fear and awe the Gubbins struck into the heart of moorland travellers, as Amyas Leigh and Salvation Yeo travelled to Bideford in the autumn of 1583. ” … it was by no means a safe thing in those days to travel from Plymouth to the north of Devon; because, to get to your journey’s end, unless you were minded to make a circuit of many miles, you must needs pass through the territory of a foreign and hostile potentate, who had many times ravaged the dominions and defeated the forces of her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, and was named (behind his back at least) the King of the Gubbings … Amyas, in fear of these Scythians and heathens, rode out of Plymouth on a right good horse, in his full suit of armour, carrying lance and sword, and over and above two great dags, or horse pistols; and behind him Salvation Yeo, and five or six north Devon men clad in head pieces and quilted jerkins, each man with his pike and sword, and Yeo with arquebuse and match, while two sumpter ponies carried the baggage of this formidable troop.

They pushed on as fast as they could, through Tavistock, to reach before nightfall Lydford, where they meant to sleep; but what with buying the horses, and other delays, they had not been able to start before noon; and night fell just as they reached the frontiers of the enemy’s country. A dreary place enough it was, by the wild glare of sunset. A high table-land of heath, banked on the right by the crags and hills of Dartmoor, and sloping away to the south and west toward the foot of the great cone of Brentor, which towered up like an extinct volcano (as some say it really is), crowned with the tiny church, the votive offering of some Plymouth merchant of old times, who vowed in sore distress to build a church to the blessed virgin on the first point of English land that he could see. Far away, down those waste slopes, they could see the tiny threads of blue smoke rising from the dens of the Gubbings; and more than once they called a halt, to examine whether distant furze-bushes and ponies might not be the patrols of an advancing army. It is all very well to laugh at it now, in the nineteenth century, but it was no laughing matter then; as they found before they had gone two miles farther.” In the book the travellers are attacked by a dozen of the ‘savages’ and Salvation Yeo kills them all including their leader. Rowle was killed at the Dartmoor Inn which is located just outside Lydford.

Fuller, in his book ‘Worthies of England’ written in the seventeenth century, conjures up a vivid picture of them when he wrote:

“The Gubbings land is a Scythia within England, and they be pure heathens therein. It lyeth near Brentor, in the edge of Dartemore. It is reported that some two hundred years since, two strumpets being with child, fled hither to hide themselves, to whom certain lewd fellows resorted, and this was their first original. They are a peculiar of their own making, exempt from Bishop, Archdeacon, and all authority either ecclesiastical or civil. They live in cotts (rather holes than houses) like swine, having all in common, multiplied, without marriage, into many hundreds. Their language is the drosse of the dregs of the vulgar Devonian; and the more learned a man is the worse he can understand them. During our Civil Wars, no soldiers were quartered amongst them, for fear of being quartered amongst them. Their wealth consists in other men’s goods, and they live by stealing sheep on the More, and vain it is for any to search their Houses, being a work beneath the pains of a Sherriff and beyond the powers of any constable. Such their fleetness, they will outrun many horses; vivaciousness, they outlive most men; living in the ignorance of luxury, the Extinguisher of Life, they hold together like burrs; offend one, and all will revenge his quarrel.“

Clearly this writer was none too enamoured with the Gubbinses and paints a picture of a tribe/clan of rough living people who were above the law and made their coin by sheep stealing and theft. Fuller suggests that the name Gubbings was attached to the tribe as a term of abuse, gubbings were ‘worthless sharings of fish’. The modern meaning of gubbins according to the Oxford Dictionary of English is: “miscellaneous items; paraphernalia originating in the 16th century from gobbon meaning ‘piece, slice, gob’ which itself derived from the Old French word ‘gobbet’ which was a piece or lump of flesh, food, or viscous matter.”

In her novel ‘Warleigh’, Anna Eliza Bray also uses the legendary Gubbinses as characters in the story. She writes of Roger Rowle as being; “… as lawless as he was brave, was the Robin Hood of Devon in times of Charles the First … However lawless might now be the life of this extraordinary person, he had once gallantly served as a volunteer in the king’s cause, and had shown, in the midst of many wild and desperate acts, a generosity and spirit of self-devotion that made his afterlife to be regretted, if not pitied, by all who honoured loyalty and courage.“She then goes on to describe the actual Gubbins tribe:”Though the followers of Roger Rowle, at the time we introduce them to the reader, assuredly deserved no other name than that of banditti, yet in the first instance, they were not unworthy of pity – since injustice, cruelty, and persecution had driven them into distress; and afterwards, rendered desperate by the want of that mercy which, if timely shown might have reclaimed them, they became confirmed in aggression, they became confirmed in their errors till, totally hardened by repeated acts of violence and aggression, they were both hunted and dreaded by all of the county … One of their family had been a dealer in cattle, and his trade was so considerable that, during some years of industry, he had amassed a fortune sufficient to enable him not only to provide for his own offspring (who were in number seven sons and three daughters), but also to assist poor kindred of the third and forth degree, so like a Scotch clan, the Gubbinses of Devon were a combined and powerful family amongst the yeomanry of the county. They were all to a man devoted to the cause of King Charles, and some of them had served him in more than one action.” In the novel, the chain of events that led to the Gubbinses changing from loyalist worthies to marauding bandits began with the seduction of John Gubbinses daughter by an officer in the Royalist army. A complaint to the garrison commander, Sir Richard Grenville, resulted not in the requested punishment of the officer but several of the Gubbinses being imprisoned in Lydford Castle. Rowle then led an attack on the gaol and released his clansmen. This resulted in the whole tribe leaving their homes and living on the moors. John Gubbins was eventually caught and hanged for which Rowle embarked on a campaign of revenge. The officer who seduced the girl was slain and the Gubbinses waged war on all by robbery and plunder.

Mrs Bray wrote again in the nineteenth century: “In Camden the inhabitants of a neighbouring village, called the Gubbins, are stated to be ‘by mistake represented by Fuller (in his English Worthies) as a lawless Scythian sort of people.’ The writer contents himself with asserting that it is a mistake, though upon what authority does not appear; as even at the present day the term Gubbins is well known in the vicinity, though it is applied to the people and not the place. They still have the reputation of having been a wild and almost savage race; and not only this, but another name, that of cramp-eaters, is still applied to them by way of reproach. Instead of buns, which are usually eaten at country revels in the West of England, the inhabitants of Brent Tor (Gubbins) could produce nothing but cramps, an inferior species of cake; probably owing to the badness of their corn, from the poverty of the soil.”

Baring Gould, 1982, p.136, writing in 1900 remarks: “It cannot be said that the race is altogether extinct. The magistrates have had much trouble with certain people living in hovels on the outskirts of the moor, who subsist in the same manner. They carry off lambs and young horses before they are marked, and when it is difficult, not to say impossible, for the owners to identify them. Their own ewes always have doubles,” – Whitlock, 1977, p.81.

It has been suggested that their very lifestyle led to their final demise. Many stories state how they shared all things including their wives and so it was inbreeding (and intemperance) that finally wiped them out along with a gradual conversion to Christianity. It is said that Jesuit priests hid in Lydford Gorge to avoid Cromwell’s troops and it is they who may have responsible for the conversions. Samuel Rowe, 1985, p.430, notes that many of the later writers make no reference to the Gubbins and concludes that by the middle of the seventeenth century the clan ceased to exist. However, according to the 1851 census there were nine families named Gubbins that were born in the Tavistock area alone, most were agricultural labourers and miners.

Baring Gould, S. 1982 A Book of Dartmoor, Wildwood House, London.

Brown, W. 1644 A Lydford Journey.

Norris, G. 1986 West Country Rogues and Outlaws, Devon Books, Exeter.

Rowe, S. 1985 A Perambulation of Dartmoor, Devon Books, Exeter.

Soanes, C & Stevenson, A (eds) 2003 Oxford Dictionary of English, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Whitlock, R. 1977 The Folklore of Devon, Batsford, London.

Family History Resource Files CD Rom, 1997 1851 British Census

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Out of curiosity I typed “Gubbins” in search engine.

“gubbins” definition: something unspecified whose name is either forgotten or not known

So perhaps the real name was forgotten, or deliberately hidden by the wild group by use of that word for their “family name”, and “gubbins” was somehow substituted for the actual name of the people?

Given the times, one cannot help wondering whether the group deliberately made a fearsome repution for the area, to keep people away. I find it interesting that soldiers (Cromwell’s?) were fearful of camping nearby, yet priests could go there. Given that Cromwell’s troops were involved, perhaps they were less “inbred” than was said about them, but rather a part of the “underground” of Catholics fearing for their lives, and needing a temporary place to live until they could somehow sail away to safer shores? Just a thought. It might fit in with the priest-holes and hidden closets in some grander houses as well…

At any rate, people of the name are found in other areas of GB, and seem to include some fine citizens.