“I have a dream…” as most of us do but usually it does not involve transforming a whole landscape. Back in the 1800’s one man’s dream was to recreate a mystical land on Dartmoor, he wanted to bring the Isle of Mona to the moor along with a fabulous grotto in which Merlin the Magician could live. On the Cowsic river he wanted to carve dedications to all his heroes, in particular the Druids, upon the rocks and boulders which stood in its gushing torrent. In short The Reverend Bray wanted a druidical landscape in which he could wander and contemplate his navel and that’s exactly what he did. Yes that’s right, the reverend was besotted with the Druids which does seem slightly to contradict somewhat – Christian, pagan? In the days before the Dartmoor National Park Authority it was possible to do almost anything on Dartmoor provided you had the money and did not offend the Duchy of Cornwall. In many cases along as the wages were good the men of the moor would go along with most ideas regardless of their seeming stupidity and help them come to fruition. Accordingly Mr. Bray’s family had the money which along with his ‘dream’ has still left feint traces in and around Beardown.

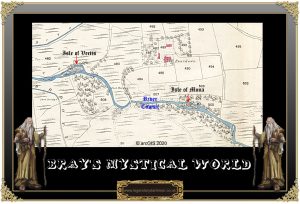

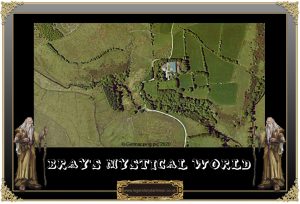

It appears that the Reverend Edward Bray first got his penchant for ‘graffiti’ whilst living at the Tavistock vicarage where in 1844 his wife, the indomitable Mrs Eliza Bray remarked how there were three inscriptions around the garden. One of them had lines dedicated to a former abbot of Tavistock Abbey and another to Sir Frances Drake. Other dedications were to local nobility such as the Glanvils’, Fitzs’ and the poet William Browne. In around 1802 the Mr Bray, senior, acquired Beardown which was promptly enclosed and a house built. Edward Bray considered that the name of the area – Beardown derived from ‘Bardun‘ or the ‘Hill of Bards’. This fitted in admirably with his theory that nearby Wistman’s Wood derived its name from ‘Wood of the Wisemen‘ who were the druids. Amazingly the other tradition that Beardown literally derived from the fact that this was where the last bear was killed on Dartmoor was dismissed as fanciful by Bray. Alright, so here we have Mr Bray living at a house which has been built on his ‘Hill of Bards’, he has a great passion for poetry and druids and is into graffiti. The first thing he does is to name the small island in the Cowsic river below Beardown Farm – The Isle of Mona. On the island Edward Bray noted how:

“I propose to put none but Druidical inscriptions, principally in the form of triads. These shall be in bardic character, as they are represented in Davies’s ‘Celtic Researches.’ By way of amusement to those who may wish to decipher them, I shall mark this simple alphabet on a white rod, and call it the virgula divinatoria, or the diviner’s wand, which is still so celebrated among the miners, so that literally few, if any, will be able to understand it without the assistance of this magic rod. It will add to the effect to call a recess, or kind of grotto, that is contiguous to this island, Merlin’s Cave, and on a rock, which may be considered as his tomb, to inscribe – ‘These mystic letters would you know, Take Merlin’s wand that lies below‘.”

Once again the druidical influence can be seen in the choice of name for the island as Mona or Yns Mons is Anglesey which was once the holy isle of the druidsThe next part of Bray’s plan was to, “consecrate” certain rocks and boulders to his poetical and druidical heroes which basically meant he wanted to dedicate a rock to each of his druids and poets and then inscribe, “select passages,” from their work – in Latin. He then had a rethink because in some cases the words would be have to be spelt in capital letters which meant a lot of carving. Consequently it was then decided to go ahead in English which would entail Edward Bray painting the required wording on the rocks and then employing a workman to actually cut them with a pick into the granite. It was also deemed a good idea because the, “common mason,” probably didn’t have a command of Latin and therefore English would result in fewer mistakes – no kidding! The concept of the plan eventually turned out to be the following:

“… in so wild and solitary a scene as Dartmoor, was not without effect: it seemed to people the desert; at any rate one might exclaim that ‘The hand of man has been here!’ I then conceived that it would give more animation to the scene by adding something either addressed to, or supposed to be uttered by, these fancied genii or divinities of the rock; and accordingly, for the sake of conciseness as well as trial of skill, composed them in couplets.

For those not of a poetical bent it’s probably as well to move onto another page because now will follow the short works of Edward Bray which he proposed to carve all over the moor, Bray (1844, pp 78 – 89)

Inscription the first.

To my Father.

Still lived the Druids, who the oak revered,

(For many an oak thy peaceful hands have reared)

The hill of bards had echoed with thy name,

Than warrior deeds more worthy songs of fame.

No. II. To the Same.

Who gilds the earth with grain can bolder claim

The highest guerdon from the hands of Fame,

Than he who stains the martial field with blood,

And calls from widowed eyes the bitter flood.

No. III. To the Same.

This tender sapling, planted now by thee,

Oh! May it spread a fair umbrageous tree;

Whilst seated at thy side I tune my lays,

And sing beneath its shade a father’s praise.

DRUIDICAL AND OTHER INSCRIPTIONS.

No. I.

Ye Druid train these sacred rocks revere,

These sacred rocks to minstrel spirits dear!

If pure your lips, if void your breast of sin,

They‘ll hear your prayers, and answer from within.

No. II.

Read only ‘thou these artless rhymes

Whom Fancy leads to other times; Nor think an hour misspent to trace T

he customs of a former race:

For know, in every age, that man

Fulfils great Nature’s general plan.

No. III.

Oh! Thou imbued with Celtic lore,

Send back thy soul to days of yore,

When kings descended from their thrones

To bow before the sacred stones,

And Druids from the aged oak

The will of Heaven prophetic spoke.

Inscriptions on the rocks of Bair-down, in the river Cowsic:

To Merlin.

Born of no earthly sire, thy magic wand

Brought Sarum’s hanging stone from Erin’s land:

To me, weak mortal! no such power is known,

And yet to speak I teach the sacred stone.

Inscriptions in Triads, etc.

No, I

Though worshipp’d oft by many a different name,

God is but one, and ever the same,

To him at last we go, from whom at first we came.

No. II

Know, though the body mouldered in the tomb,

That body shall the living soul resume,

And share of bliss or woe the just eternal doom.

No. III

Proud man ! consider thou art nought but dust;

To Heaven resign thy will, be good, be just,

And for thy due reward in Heaven with patience trust.

No. IV

Their earthly baseness to remove,

Souls must repeated changes prove,

Prepared for endless bliss above.

No. V

Adore great Hu, the god of peace;

Bid war and all its woes to cease;

So may or flocks and fruits increase.

No VI

To Odin bow with trembling fear,

The terrible, the God severe:

Whose bolt of desolating fire,

Warns not, but wreaks his vengeful ire;

Who roars amid the bloody fight;

Recalls the foot that turns for flight;

Who bids the victor’s banners fly;

And names the name of those who die.

Inscriptions to the bards alluded to by Grey.

To Cadwallo

Mute is thy magic starin,

“That hush’d the stormy main.”

To Hoel

Thy harp in strains sublime express’d

The dictates of thy “high born” breast.

To Urien

No more, awaken’d from thy “craggy bed,”

Thy rage-inspiring songs the for shall dread.

To Llewellyn

Mid war’s sad frowns were smiles oft wont to play

Whilst pour’d thy harp the “soft,” enamour’d “lay.”

To Modred

Thy “magic song,” thine incantations dread,

“Made huge Plinlimmon bow his cloud-topt head.”

Additional Triads

No I – From Mela

The soul’s immortal – then be brave,

Nor seek thy coward life to save;

But hail the life beyond the grave.

Another from Diogenes Maertius

Adore the Gods with daily prayer,

Each deed of evil shun with care,

And learn with fortitude to bear.

Alluding to the Druid’s belief in the Metempsychosis

Here all things change to all – what dies,

Again with varied life shall rise:

He sole unchanged who rules the skies.

Alluding to the Druidical Sprig Alphabet

Hast thou the knowledge of the trees?

Press then this spot with votive knees.

And join the sacred mysteries.

A Triad, founded on the maxims of the Druids in Rapin’s History of England

None must be taught but in the sacred grove:

All things originate from Heaven above;

And man’s immortal soul a future state shall prove.

Inscribed on a rock in the river Cowsic, the banks of which he had planted.

To my father

Ye Naiads! venerate the swain

Who join’d the Dryads to your train.

Inscription for an Island in the river Cowsic, to which I have given the name of Mona.

Ye tuneful birds! ye Druids of the grove!

Who sing not strains of blood, but lays of love,

To whom this Isle, a little Mona’s given –

Ne’er from the sacred spot shall ye be driven.

Inscription for a rock on the lower Island.

Who love, though e’en through desert wilds they stray,

Find in their hearts companions of the way.

For the same Island.

To thee, O Solitude! we owe

Man’s greatest bliss – ourselves to know.

Inscription on a rock in the woods near the Cowsic.

The wretch, to heal his wounded mind.

A friend in solitude will find;

And when the Blest her influence tries,

He’ll learn the blessings more to prize.

For a rock on Bair-Down.

Sweet Poesy! fair Fancy’s child!

Thy smiles imparadise the wild.

Inscription for an Island on the Cowsic, to which I have given the name of Vectis.

When erst Phœnicians cross’d the trackless main

For Britain’s secret shore, in quest of gain,

This desert wild supplied the valued ore,

And Vectis’ isle recieved the treasured store.

For a rock in Wistman’s Wood.

The wreck of ages, these rude oaks revere;

The Druid, Wisdom, sought a refuge here,

When Rome’s fell eagles drench’d with blood the ground

And taught her sons her mystic rites profound.

For the same.

These rugged rocks, last barrier to the skies,

Smoked with the Druids’ secret sacrifice;

Alas! Blind man, to hope with human blood to please a God, all-merciful, all good.

Inscription for a rock on Bair-Down.

Mute is the hill of bards, where erst the choir

In solemn cadence, struck the sacred wire:

Yet oft, methinks, in spells of fancy bound,

As swells the breeze, I hear their harps resound.

Inscription near the Island.

Learning’s proud sons! Think not the Celtic race,

Once deemed so rude, your origin disgrace:

Know that to them, who counted ages o’er,

The Greeks and Romans owe their learned lore.

Inscription for a rock near the Cowsick.

Here, though now reft of trees, from many an oak

To Druid ears prophetic-spirits spoke;

And, may I trust the muse’s sacred strain?

Reviving groves shall speak of fate again.Near the same.

Ye minstrel spirits! When I strike the lyre,

Oh, hover round, and fill me with your fire !

To .Boadicea.

Roused by the Druids’ songs, mid fields of blood,

Thine arm the conquerors of the world withstood.

To Caratacus

Imperial Rome, that ruled from pole to pole,

Could never tame, proud chief, thy mighty soul

To Taliesin.

How boiled his blood! How thrilled the warrior’s veins!

When roused to vengeance by thy patriot strains.

To Fingal and his Bard

spirit of Loda! round their shadowy king,

Here may the ghosts of song his deed of glory sing.

To Carril.

Mid flowing shells, thy harp of sprightly sound

Awoke the mirth the festive warriors round.

To Ossian.

When sings the blast around this mossy stone,

I see thy passing ghost, I hear thy harp’s wild tone.

To Cronnan.

Oft to the warrior’s ghost of mournful tone,

Thy harp resounded near his mossy stone.

To Ryno.

First of his sons of song, thy war-taught string

Defiance spoke from woody Morven’s king.

To Ullin.

Son of the harp of Fame! thy fateful power

Could fill with joy the warrior’s dying hour.

To Malvina.

Oft thy white hand the harp of Ossian strung,

When, hapless sire, thine Oscar’s fate he sung.

To Minona

Thy harp’s soft sound, thou fair-hair’d maid, was dear,

More dear thy voice to Selma’s royal ear.

To the Cowsick.

To thee, fair Naiad of the crystal flood offer not the costly victim’s blood;

But as I quaff thy tide at sultry noon, I bless thee for the cool reviving boon.

To Aesop

E’en solitude has social charms for thee,

Who talk’st with beast, or fish, or bird, or tree.

To Thomson.

To Nature’s votaries shall thy name be dear,

Long as the seasons lead the changeful year.

To Shakespeare.

To thee, blest bard, man’s veriest heart was known,

Whate’er his lot — a cottage or a throne.

To Southey, for a rock in Wistman’s Wood.

Free as thy Madoc mid the western waves,

Here refuged Britons swore they ‘d ne’er be slaves.

To Savage.

What! though thy mother could her son disown,

The pitying Muses nursed thee as their own.

To Spenser.

The shepherd, taught by thine instructive rhyme,

Learns from thy calendar to husband time.

To Shenstone.

Nurtured by taste, thy lyre by Nature strung,

Thy hands created what thy fancy sung.

To Browne.

I bless thee that our native Tavy’s praise

Thou ‘St woven mid Britannia’s pastoral lays.

To Burns.

Long as the moon shall shed her sacred light,

Thy strain, sweet bard, shall cheer the Cotter’s night.

To Collins.

In orient climes let lawless passions rove,

Blest be these plains with friendship and love.

To Bacon.

Thy prayers induced Philosophy on earth

To call the sciences and arts to birth.

To Walton.

The angler’s art who from thy converse learns,

Happier and better to his home returns.

To Falconer.

Oft shall the rustic shed a feeling tear

The shipwreck’d sailor’s piteous tale to hear.

To Dante.

To faith, not purgatory, know ’tis given,

To shut the gates of hell, and open the gates of Heaven.

To Rowe.

Oh turn, ye fair, from flattery’s voice your ear,

Nor live to shed the penitential tear.

To Mathias.

On Thames’ loved banks thou strik’st Ausonian lyre,

And call’st from Arno’s waves the minstrel choir.

To Watts.

The pious rustic from thy sacred lays

May learn to sing the heavenly shepherd’s praise.

To Rochester.

Dearer than self was nothing to thy breast –

Now, since thou’rt nothing, sure thou’rt doubly blest.

To Aiken.

Nature’s free gifts thou taught’st th’ admiring swains

To calendar, and praise with grateful strains.

To Scott.

Cease not thy strains; from dawn till close of day,

I’d list, sweet minstrel! to thy latest lay.

To Wieland.

Thy magic wand, by Oberon’s fairy power

Mid barren wilds can weave love’s roseate bower.

To Varro

Thy Patriot virtue taught the happier son

To turn the soil his father’s falchion won.

To Chaucer.

Ride though thy verse, discordant though thy lyre,

Each British minstrel owns thee for his sire.

To La Fontaine.

He taught the beasts that roam the plains

To speak a moral to the swains.

To Cowley.

Oft mid such scenes the livelong day

“The melancholy Cowley” lay.

To Young.

Oh! lead my thoughts to Him, the source of light,

Ere sleep enchains them in the cave of night.

To Parnell.

Oh! be mine with men to dwell,

But oft to seek the hermit’s cell.

To Gray.

The youthful swain, where his “forefathers sleep,”

Shall sing thine elegy, sweet Bard! and weep.

To Rogers.

To every swain grown grey with years

Memory his native vale endears.

To Akenside.

Imagination’s airy dream

Finds Naiads in each purling stream.

To Anne Radcliffe.

Nature, enthusiast nymph! a child

Found thee, and nursed thee in the wild.

Don’t even think it, you reckon it’s been hard work, if you’re still with us that is, I have just spent the last two hours typing out this load of old guff. Thankfully, his poor wife does mention that in her book she did not include another 115 of the distichs or couplets. Seems like even she got hacked off transcribing them and she was his wife. The only thing I will say is, thank God Edward sodding Bray didn’t have this idea today, imagine the hundreds of modern poets that would be added to this list. It would take every rock and boulder on Dartmoor to carry his manic verses. I am off to down a bottle of Islay whisky in an effort to recover the vaguest sense of happiness – see you late, much later.

Ok, that’s better, at least I now only have a thumping hangover. Needless to say this scheme of Edward Bray’s never came to complete fruition. He probably couldn’t find a, “common mason,” daft enough to stand out on the open moor carving such twaddle. Actually that’s not true because he must have found one game enough to give it a try because a number of rocks and stones got carved with some of the dedications. Hemery, (1983, p.395) notes that:

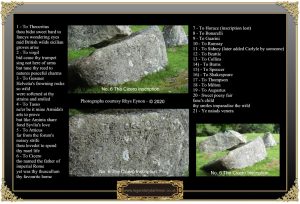

“Few of the couplets ever reached the rocks but the dedications did, and those easiest to discover and read lie immediately below the bridge (the old clapper bridge). The large horizontal boulder above the left bank bears a distich, or couplet, addressed to Atticus; this one is not included in Tamar and Tavy by Mrs Bray… Easily discernable in the river-bed are “To Shakespeare”, “To Milton”, “To Spencer” and “To Homer“.

He also says (p.397) how on a large boulder above Beardown clapper bridge has the, “Sweet Poesy! fair Fancy’s child! Thy smiles imparadise the wild.” couplet inscribed on it. This was written 24 years ago and time, mosses, lichens and the Dartmoor weather will have taken their toll on the works, thus making them hard to find. The above list was written in 1802 and by 1844 Eliza Bray (p.70) was even commenting that;

“Some of these inscriptions are now so moss-grown, so hidden with lichen, or so worn with the weather and the winter torrents, that a stranger, unless he examined the rocks at a particular hour of the day when the sun is favourable, would not be very likely to discover them.”

In his book Page 91895, p.155) seems a bit non-plussed by it all:

“… Some of them are inscribed with characters which have probably deluded many a tourist, who has departed proud of having discovered some mystic symbol of primeval times. They are the ‘bardic’ letters carved by the late Rev. E. A. Bray, and were intended to be distichs and triads to the Druids, in whom he was an intense believer – to Merlin, Boadicea, Caractacus, and other famous Britons, as well as to more modern poets It is feared that not even the wand which he suggests as a key would enable the degenerate translator of the later half of this century to decipher the legends, more especially as the elements have rendered them so indistinct that not even the Arch-Druid himself would be much the wiser for their perusal.”

I imagine he is only referring to the Ogham or, “bardic character,” inscriptions that were placed on and, “contiguous” to the Isle of Mona as the rest were in English. The two inscriptions on the Isle of Mona were translated by French (1990, p.20) which slightly contradicts Page’s remarks, and read:

“The soul’s immortal, then

Be Brave

Nor seek thy coward life

To save

But hail the life beyond

The Grave”.

“Adore the gods with daily

Prayer

Each deed of evil shun

With Care

And learn with fortitude to bear”.

The final result was that 21 inscriptions were actually completed and of those 6 had their couplets as can be seen from the list above.

But joking apart, I think what we are seeing in this scheme of Edward Bray’s are two concepts of his time. During the 1800’s there was, amongst the upper classes, a move towards the picturesque concept of wild, rugged landscapes. It became the fashion to go out and appreciate such features and large landowners created walks amongst amongst such scenic places and embellished them with follies, grottoes, etc. Probably one of the most famous of such walks is that at Piercefield Park near Chepstow. Here in the late 1700’s Valentine Morris laid out a walk embellished with follies, grottoes and viewpoints that took people around the rugged landscape of the Wye Valley. Could it just be that Bray was trying to do the same? Perhaps his idea was to guide people around a trail of inscriptions that would lead through the so-called wild and rugged landscape of Dartmoor. He not only embellished the land with his inscriptions he also ‘created’ a natural grotto and re-named a small river island to add to the effect. The roots of this desire to add and embellish upon natures work on the landscape has been inherent since early man began building ritual monuments. So this, I would suggest, is merely a later manifestation of such tendencies coupled with the picturesque vogue of the time. This along with his ‘obsession with Druids allowed him to create an imaginary landscape where history was combined with the picturesque. After all, Bray actually admits this desire when he stated, as above, “one might exclaim that ‘The hand of man has been here'”.

Bray, E. A. 1844 Legends, Superstitions and Sketches of Devonshire on the Borders of the Tamar and the Tavy, A. K. Newman & Co., London.

French, H. 1990 Sermons in Stones, Dartmoor Magazine, No. 20, Quay Pub., Brixham.

Hemery, E. 1983 High Dartmoor, Hale Publishing, London.

Page, J. Ll. W. 1895 An Exploration of Dartmoor, Seeley & Co., London.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Hi Tim

I had a go at writing about the visible stones and inscriptions in Dartmoor Magazine Summer 2021. Would you be willing to add my article to your reference list

T. Jenkinson (2021) Dartmoor Discovered The Beardown Inscriptions DM 142 Summer 2021.

Cheers

Tim

Hello there, I discovered one of these while camping at Beardown Farm. Looked like the bardic style and included the words Imperators at the front and ‘miles imperadi’ towards the end. Could you tell me if you have the translation for this one and who it was dedicated to?

many thanks

Chris

Hi Chris, which of the stones was this Imperators inscription upon?? Kindest wishes Simon