Since the days when the ancient folk lived in hut circles on the moor there have been sacred stones. Some of them were formed into granite circles others were lined up like ranks of warriors. For really special places, huge solitary pillars were erected to stand guard over the tribal lands. It was in and around these sacred stones that the ancients were buried in granite lined graves. Having lowered the mortal remains into these stony chests the ancients would then place a huge capstone over the graves and cover them over with piles of moorstone rock, which from a distance made for an impressive site. For as long as anybody can remember these grim granite tombs were known as kistvaens.

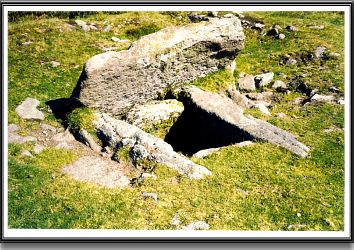

A Dartmoor Kistvaen.

Ever since those long forgotten days the tombs of the dead have always been regarded as sacred places that should never be disturbed. Many tales were told of the graves, moorfolk believe that they were the tombs of mighty tribal leaders or warriors and that much of their wealth was buried with them for use in the afterlife. The kistvaens even had individual names, all promising wealth and riches such as the ‘Crock of Gold’, the ‘Money Pit’, the ‘Gold Box’, Grandpa’s Chest and the ‘Money Box. From the day any child of the moor took its first tottering steps amongst the peat and heather they were told never to interfere with the kistvaens for it was sure “t’would be a mortal sin an’ no good ‘ud com’ on it.” But as always there are those whose greed overcomes them despite any dire warnings that have been given them. For example there was the farmer who raided the ‘Money Pit‘ and no good became of him.

Then there was the ‘Parson’, many say that he was actually a man of the cloth, in which case he should have known better. But parson or not he had heard the old stories about the riches that lay buried beneath the now grassy mounds. Whenever he walked by an old kist his thoughts would turn to what lie beneath the tell tale heathery mounds. Every now and then he would go and examine one, prodding and poking just in case anything of worth could be found. Naturally the less cynical would assume that any riches he may have found would have been spent on the upkeep of his church or the well being of his flock but there were those that were not so sure. As the seasons changed from one to another the lure of the kists became stronger and stronger. The parson’s walks became longer and longer and as he ventured over the moor he would plot the location of every kist he found. Before long his map had more black dots on it than a ladybird has on its back.

Eventually the man plucked up enough courage to go and open one, he chose a secluded hump hidden away from prying eyes. After a morning’s work of prising away the covering rocks he eventually came to a massive flat granite slab, but try as he might, there was no way he would be able to shift it on his own. So, beaten but not lost he trudged wearily home. That night he went to visit a couple of notorious characters who would do literally anything for a purse of coin. The parson explained why he wanted their help and what he wanted it for. Amazingly, even these characters were a trifle edgy at the proposition of breaking into the ancient tombs, but the lure of easy pickings eventually persuaded them otherwise. Tomb after tomb was raided and despoiled and gradually the parsons hoard grew big and shiny with gold coins. It was clear that the new found wealth was not going to be spent in God’s work but was to become the miser’s hoard.

Finally the day came when the parson and his helpers had opened every black dot on his map which meant there was to be no more riches. He spent a few desperate days trying to locate some more of the ancient graves but to no avail, he was now a rich man but this was not enough. Folks say that at nights the parson could be seen counting all his treasures by the light of a flickering candle. That is until the fateful dark stormy night when a mighty thunderstorm came crashing across the moors. To this day, never the likes had been seen again, the lightening streaked vividly across the dark, sinister moorland skies and the thunder crashes shook even the mightiest of the granite tors. Not a soul dared venture outside their cott doors and the cattle cringed in their stalls. It seemed as if the storm raged all night, people were amazed at the venom of the deluge, they were even more surprised to see a bright yellow sunrise the following morning, it was as if the storm never was. What they were not surprised to see was that the only house to suffer any damage was the parsons house. To say it “suffered damage” is a understatement, the house was completely demolished to a pile of rubble with all its contents and occupant buried deep beneath the smouldering heap of granite blocks. Even more alarming was the smell of burning brimstone that hung over the ruins of the parson’s house. Many said at the time that the spirits of the disturbed ancients had sent the Devil to exact revenge for having their tombs desecrated, hence the smell of brimstone. Others remarked that it was befitting that the greedy parson should be buried in a granite tomb covered with a cairn of moorstone.

There are the remains of many kistvaens on Dartmoor, normal archaeological terms refer to them as cists. It is interesting to see the various writer’s definitions of a kistvaen, to this end I have included the full text as a comparison of the changing opinions over the past 120 years. In 1844 Mrs Bray describes how she ‘excavated’ a kistvaen:

“In the middle of it is a hollow in the form of a diamond, or lozenge, which is undoubtedly a kistvaen, or sepulchral stone cavity. It was almost concealed with moss, but with some difficulty we dug to the depth of three feet; and discovering nothing thought it useless to dig farther, as in appearance we had reached the natural stratum, which was of a clayey substance, below the black peat. It is probable that nothing was deposited there but ashes.“

Fifty years later, Page, 1895, p.48-9, noted that:

“The Kistvaen or stone coffin (cist, a chest, and maen or vaen, a stone) has a connection with barrows and much more intimate than that of the cromlech. In fact, this sepulchre of the aboriginal Briton was generally enclosed in a tumulus; and though many have been found upon Dartmoor quite denuded of an earthly covering, there is no reason to believe that they were always thus open to the elements. The construction was of the simplest. Thin granite slabs formed the sides and the stones for the head and feet, while a similar flag acted as a lid, and protected the corpse from the soil. This coverstone has seldom been found intact; if it has not altogether vanished, it will be found broken in the cavity or near at hand. Few of these coffins are of a shape which admits of the figure being stretched to its full length: the knees of the departed were drawn up under the chin prior to internment.“

A Kistvaen near the Langcombe.

The early antiquarian, Robert Bernard, writing in 1900 remarks how kistvaens:

“Unfortunately they have been rifled, and their contents dispersed and destroyed, with little or no record of the finds to serve as a guide to the antiquary… These pre-historic graves were rifled at a time when archaeology was unknown, and the particular notion that they contained articles of value still survives in some of the names by which they are named “money pits,” “money boxes,” and “crocks of gold;” whilst others know them as caves, Roman Graves, stone graves, or simply graves.”

An early depiction of a kist by R. Burnard 1890.

A few years later, in 1900, Sabine Baring Gould,1982, p.57, gives his observations of kistvaen plundering in the following way:

“On Dartmoor there are many hundreds of these kistvaens, of various sizes, but most have been rifled by treasure-seekers; indeed, all but such as were covered with earth and so escaped observation have been plundered.”

Seventy years later, in 1974, Petit, pp.109-122, devotes a whole chapter to a discussion on Dartmoor kistvaens, the salient points being:

“The small stone burial chambers known as kists are still numerous on the Moor.. Over a hundred have been found by the energetic. All have been ravaged by many generations of plunderers yet the stones of some are complete. The majority lie in the valleys of the Dart, Plym and Meavy; only a score are recorded elsewhere. …the distribution suggests that beaker occupation was in a broad band north-east-south-west across the Moor…”

In 1997, Butler, pp. 168-187, also devotes a whole chapter on the cists/kists of Dartmoor, the jist of which is:

“… Typically cists are four-sided stone boxes with a cover slab and occasionally a paved stone floor… Most were sunk into the sub-soil to some extent, sometimes completely so that the top edges were flush with the original ground level. Others seem to have been almost free standing on the surface, supported at one time by the stones of a cairn, like the fine but restored examples at Roundy Park.”

‘Freestanding’ kistvaen at Roundy Park.

Not uncommonly cists or retaining circles are the only evidence of a burial site and those with little or no trace of a mound are usually close to roads or newtakes or in regions known to have been the target of stone collectors (for building purposes)… Cisted graves are widespread, present distribution merely reflecting the accidents of survival, their ubiquitous siting ranging from hilltop to riverbank… About 187 fairly certain examples have been recorded on the Moor… Most of these, already exposed were cleared out again by members of the Dartmoor Exploration Committee and only two have been found undisturbed… “

And so the list of extracts could go on, but as can be seen from the above examples all agree as to their design and purpose and more importantly all note how the kistvaens have been plundered by treasure seekers. Clearly, when in the early days, the graves were opened there would have been no fabulous treasure hoards. Gerrard, 1997, p.57, notes that around 53 cairns produced finds comprising of flint artefacts, pottery, quartz crystals, dress fasteners, bronze knives, bronze spearheads, glass beads, a dagger pommel, rivets, a stone amulet and faience beads. Obviously, if you had spent a hot sweaty day digging into a kistvaen none of the above finds would have been regarded as ‘treasure’, they certainly would not make you rich. These days things would be different and in an archaeological context some of them would be regarded as priceless.

A newspaper report from 1924 stated the following:

“In one of the wildest parts of Dartmoor, near Okehampton, 800ft above the sea-level excavations have revealed traces of population by a prehistoric tribe. Ancient earthworks, burrows and tumuli exist in the vicinity, and there has now been dug up a large number of rude stone implements, which authorities state are of great antiquity. They include axeheads, spearheads, rubbing-stones, and hammer stones, and date back to a period before flint instruments were used. The specimens have been offered to the British Museum and the Plymouth and Exeter museums, and the owner of the property, Mr (F?)Reddie Mallett is continuing his researches, and states that should future discoveries prove of sufficient value, he will build a small museum on the site for the exhibition of the finds.”

So here as late as 1924 there is somebody who hopes he will get enough money from his finds, researches, to build a museum on Dartmoor?

Despite the obvious cases of kists being rifled, the general traditions on Dartmoor were that they were things best left alone. Moorfolk believed that in some cases they were where the piskies lived and it some areas a flint arrowhead was called a ‘piskie-bolt’ which as some of the kistvaens have revealed such items could tie in with that belief. So maybe this and similar stories were used to instil either fear or respect for the graves of the ancients and to illustrate the dire consequences of ‘tomb raiding’.

Baring-Gould, S. 1982, A Book of Dartmoor, Wildwood House, London.

Burnard, R. 1986 Dartmoor Pictorial Records, Devon Book, Exeter.

Butler, J. 1997 Dartmoor Atlas of Antiquities, Vol. 5, Devon Books, Tiverton.

Crossing, W. 1990, Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor, Peninsula Press, Newton Abbot.

Gerrard, S. 1997, Dartmoor, Batsford, London.

Hemery, E. 1983, High Dartmoor, Hale Pub. London.

Page, J. Ll. W. 1895 An Exploration of Dartmoor, Seeley and Co, London.

Petit, P. 1974 Prehistoric Dartmoor, David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor