“And then the peat fires! What fires can surpass them? They do not flame, but they glow, and diffuse an aroma that fills the lungs with balm… I may be mistaken, but it seems to me that cooking done over a peat fire surpasses cooking at the best club in London. But it may be that on the moor one relishes a meal in a manner impossible elsewhere.“ Sabine Baring Gould, A Book of Dartmoor, p.180

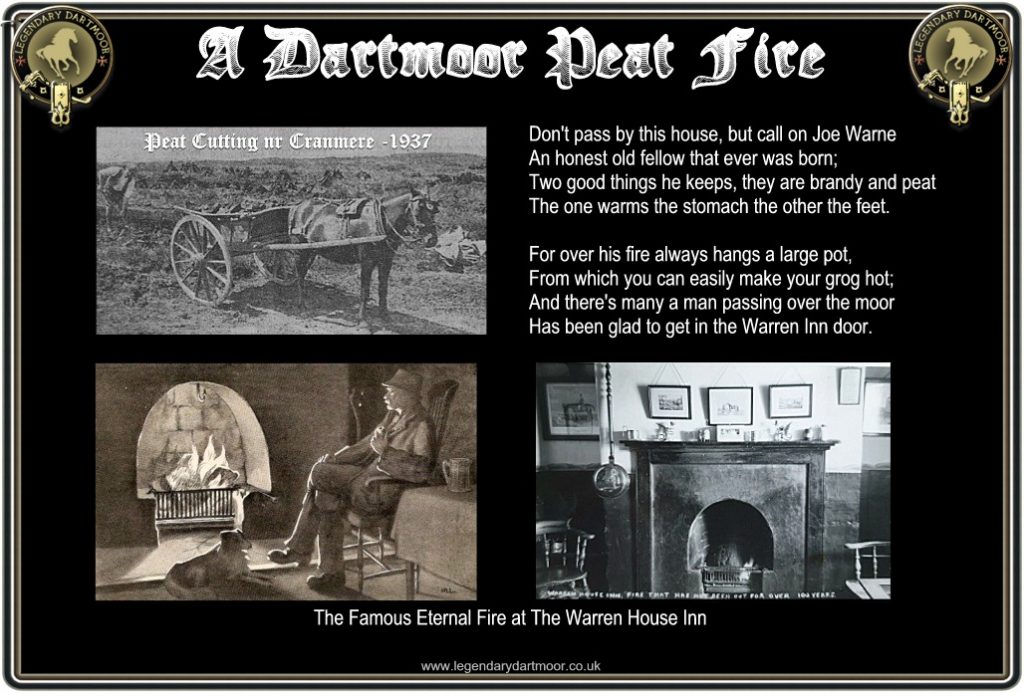

For centuries the Dartmoor folk relied on peat for heating their homes, cooking their food and in some cases for selling on to earn a living. Therefore it’s no surprise that such a commodity should have played an important part in the lives of the Moor Folk. In 1937 one traveller made the following observation; “The horse and cart of the Dartmoor peat cutter, slowly jolting its way over the centuries’ old tracks leading to the peat deposits of the moor, is still a familiar sight even in these days of coal, electricity and gas. Since time immemorial peat has been the fuel of the dwellers on Dartmoor and its fringes, and any visitor to a moorland village will soon get to know the peculiar tang of its smoke.” William Crossing in respects to peat fires wrote the following: “On a hearth peat makes a capital fire, as all who have seen a “yafful o’ turve placed on the crackling fire will admit.” – p.39. He then went on to note; “Of the latter fuel (peat) there was always a plentiful supply, any quantity being available for the trouble of taking it. It was usually brought from the ties or pits, by the farmers’ horses, a service which was paid for by the labourers cutting a few loads of it for themselves. A certain number of slabs of peat constituted a load for a packhorse, and this were termed a seam.” – p.60.

On the 24th of December 1928 The Exeter & Plymouth Gazette published the ‘Idiot’s Guide’ to lighting a peat fire, it read; “To build and keep burning a fire of peat requires a little patience. A peat fire burns well and with more heat than coal, and it lasts longer. It burns away completely to a fine soft ash. It is advisable to buy a mixture of three grades of peat. One is dark and hard, the other is very soft, and the third is a medium kind. Plenty of dry sticks and very small pieces of dry peat are needed to begin a fire. When it catches alight it must be fed with small pieces of peat. Then it may be piled with large sods of peat. A little coal to start will help the fire considerably. When a peat fire becomes dark and dead-looking it can generally be revived and restored to a glowing mass by blowing it with bellows.

Most moorland homes had a ‘Turf Shed’ in which to store the peat and keep it dry. It was once estimated that a cottager would lay in around four waggons of peat to see him through the year. It was suggested that both peat and ‘veggs’ (clumps of heather or turf) were needed to maintain a fire, the peat as fuel and the turfs as a dampner for the fire.

Many of the Moor farms had an ‘Ash House‘ which was a small granite building, near to the house in which the ashes from the hearth would be stored each night. In the case of wood fires one of the reasons for such was to prevent sparks and embers being drawn up and setting alight to the thatch whilst the family were abed. In the case of both wood ash and peat ash or a combination of both this was a very cheap and useful source of fertiliser for the land as they contained beneficial plant nutrients such as phosphorous. So these structures were store houses for the ashes until it was time to spread them on the soil.

At times of war coal was of vital importance for the industrial production of arms, munitions, etc. so with this increased demand various national and local governmental bodies issued guideline for conserving that resource. These proposals were aimed at domestic users and certainly on and around Dartmoor folk were advised to look to peat and its benefits as an alternative heating source. Firstly due to the moorland deposits there was an ample local supply, it was certainly cheaper than coal and in some respects healthier. During 1915s a pamphlet was circulated called ‘Diet and Hygiene’ in which it warned about the dangers of inhaling coal fumes when living in confined spaces, (such as many of the moorland dwellings), It advised that coal fumes could cause; “feverishness, heart, throat, and head aches, and lassitude.” The stated that for those very reasons peat fires were “admittedly healthy.

Aside from domestic properties the peat fire was the main focal points in virtually all the early inns, pubs and hotels, especially on cold winters nights. There are numerous references made by travel authors describing such scenes in moorland hostelries. Many paint the scene of rustic moormen gathered around a blazing peat fire, their mugs of cider in hand whilst discussing the local news and affairs. Some mention the particular aroma of peat smoke mixed with the smell of tobacco and alcohol. This very mixture led to the distinctive and characteristic dark brown staining on the walls, ceiling and wooden beams of these inns. There are many tales of the ‘eternal fires’ that supposedly burnt in the fireplaces of Dartmoor inns. Probably the most famous one of all is at the Warren House Inn. The number of years over which it had remained constantly lit has varied. In 1927 one report suggested that by that year the old peat fire had remained lit for 120 years. Today (2109) the establishment claims that; “Our fire has been burning since 1845,” except wood logs have replaced the peat bricks. In a similar light the fire at the White Thorne Inn at Shaugh Prior was reputed to have been first lit in 1833 and was still going strong in 1933 having burnt for 100 years.

It was not only the fires of the home hearths that were fuelled with peat, on many celebratory occasions peat was used in the fires of beacon chains. In 1911 the Reverend Rawnsley issued the following advice to people building Coronation beacons; “It is suggested that, wherever possible by leave of the owner, peats should be dug at the nearest point to the summit. These, if cut thin and set up to dry without loss of time, in ordinary weather, should be ready for fuel by the 22nd June. They can be sledged up by a horse and gear a day or two before the building of the bonfire without much cost, and, if built with good air passages at the base communicating with a central chimney and saturated with a barrel of paraffin or petroleum or creosote (use a water-can sprinkler or long-ladled ladle), will burn with a steady fire for three or four hours. …The only caution needed is, that the peats should not be built solid but like open brickwork with interstices to allow air passage.””

As far as cooking with peat went there was a very descriptive piece written in the Western Times, in the April of 1892, it read; “Last week I had the pleasure if inspecting the operation of baking in a ‘Dartmoor Oven.’ An obliging housewife, who lives in a fine old homestead under the shadow of Cawsand Beacon (Cosdon), explained the method of using the almost obsolete utensil. The “Oven” is really a huge oval saucepan, resting on an iron tripod (trivet), and a fire of peat is kindled beneath it. This is a primitive mode of baking, and one that involves constant watch on the fire but the advantage is, that pies, or whatever you’ve a mind to bake, are much sweeter when cooked in one of these antiquated oven. Unfortunately, I had not the time to stay and taste the pie; therefore I cannot testify as to its sweetness from practical experience. This I regret, because my hostess was true Devonshire in the qualities of affability and comeliness. Moreover the kitchen was quaint, scrupulously clean, and had snug corners by an immense peat fire…“

As can be gleaned from above peat played a vital part in the moor folks life and should the supply ever diminish such as in wet years when it couldn’t be dried then this was a serious matter.

Back in 1910 one writer made the following remarks which emphasised the importance of peat; “What matters most is the effect of the weather on the peat. There is no wood to burn on Dartmoor, and coal even apart from cartage, makes a deep hole in the pocket. Luckily, the moorman’s fuel is at his door, and no Park Lane millionaire was ever warmed at anything better than a good peat fire. But this year the peat that is carried will be heavy and sodden. All the summer it has lain beside the ties waiting for the sun to bake it hard and dry. Once or twice it has almost been for for carrying, but each time fresh rains have come and soaked it through and through. The Dartmoor farmer may pray for a soft winter, for instead of a blaze upon the hearthstone he will have a pile of wet turves that nothing will fan out of sulky smouldering into flame.”

Therefore it should come as no surprise that various superstitions grew up around peat. To avoid such disasters one definite no-no was to cut the peat under a waning moon as it would never dry. Similarly to cut peat on a moonless night would also ensure soggy peat.

A rather complicated Christmas custom which would be used to ensure a prosperous new year was to firstly eat some Christmas pudding. Then should the person eat three raisins which had not been stoned in a single mouthful they had to look over their left shoulder into a mirror. Finally a handful of mistletoe berries had to be tossed onto a peat fire. If during this process no names were mentioned and the person never moved a muscle in their face they would be granted three wishes.

On New year’s Eve all eyes would be on the peat fire for if it merrily glowed in the hearth then this foretold of of a prosperous year ahead. However, should the fire be smouldering limply then then foretold of a coming death in the family. Another New Years belief was that if an unmarried woman took some half burned peat and kept until the next morning. Then if it was broken apart the colour of the fibrous peat inside would indicate the colour of her future husband’s hair.

At the birth of a new-born baby a piece of burning peat had to be carried around it three times this would afford protection from any piskies wishing to steal it. A lesser known belief regarded a cure for consumption which involved killing a jay and cremating it on a peat fire, the ashes would then be distilled in water and drank. For those people who had the knack of keeping a peat fire continuously burning it was vital that on May Day they let it die out. The hearth then had to be thoroughly cleaned and a new fire started to ignore this tradition would be to invite back luck upon the household. In the days of the witch hunts the only way to ensure she died was to burn her on a peat fire soaked with tar.

I think that the peat fire, albeit in a house or an inn has over the centuries been responsible for keeping many of the old Dartmoor legends, tales and superstitions alive. That may seem a rather rash statement but there were times when there was no in-house entertainment such as the television, radio, social media etc. So of an evening the family or patrons of the inns would gather around the peat fire and amuse each other by relating these old stories. Some were tales of long gone eras and others would have been more recent ones, either way they would have been passed down through the generations. Many of the pages on this website have been the result of this oral tradition which with the passing of the peat fire were recorded by various authors before coming lost for all eternity.

Rev. Canon R. A. Rawnsley 1911 The Book of the Coronation Bonfires. Carlisle: Charles Thurnam & Sons.

Crossing, W. 1987. A Hundred Years on Dartmoor. Exeter: Devon Books.

Baring Gould, S. 1982.A Book of Dartmoor. London: Wildwood House Ltd.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Brilliant read about how folks here used Pear , Rob ,of Princetown .