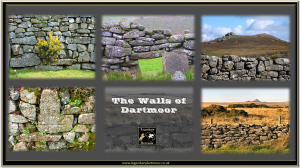

Two things Dartmoor is not short of – granite and walls and both make an integral ‘marriage’ in its landscape. What follows is some anonymous persons’ viewpoint from 1884 on the Walls of Dartmoor. Today many of what they describe can still be seen on and around the moor today. It could possibly be said that the walls of Dartmoor are a most underrated aspect of the moor and certainly not one that I have taken much notice of. As will be seen, in some cases their construction has led to a huge and regrettable loss of some of Dartmoor’s prehistoric and historic features. However, in some ways they have written a new chapter in the history of the moor through the men that built them and their purposes.

“Dartmoor is a vast mass of granite; its principal heights are crowned by “tors”; and “clatter” or “clitter,” in pieces from the size of haystacks downwards, covering many of the valley sides. Where cultivation is struggling against Dartmoor weather and Dartmoor stone, fields that seem as suitable for husbandry as Trafalgar Square are painfully ploughed and harrowed. In view of this over-abundance of stone, and the difficulty and even impossibility of growing hedges in the more exposed parts of the moor, it is not surprising that Dartmoor walls should form one of Dartmoor’s characteristic features.

Largeness, looseness, and irregularity run through most things in Devonshire, and the Dartmoor wall presents no exception to the general rule. Big blocks and little blocks carelessly compacted, are its materials; and it is very clear that considerations of convenience and not of order have brought the greater lumps towards the base. The size of many of these embedded masses of granite is enormous; some are obviously pieces of “clatter” allowed to remain in situ; others have evidently been moved and offer a pretty problem as to how many moormen and sinewy Dartmoor ponies would be required to stir them. In several of the valleys the building of walls must have helped to clear the ground (a fact which may explain the smallness of the enclosures and the thickness of the walls there), but this happy conjunction cannot have been common. Where tillage was most likely to be successful, there stone was scarcest and the toil of wall building most severe. The Devonian has, however, a happy way of taking the material nearest at hand, whether it be “cob” or prehistoric antiquities; and this disposition must have lightened his labours in the making of the Dartmoor walls. Tors have been fretted away, a sad discrowning of the hills; and the plentifulness of “kistvaen,” ancient British villages,” “trackways,” “pounds,” and “Cyclopean bridges has raised in the moorman’s heart a sincere feeling of gratitude towards the men of old. Even wayside crosses have been built into walls, or, having been sundered, the halves have been set up as gate posts.

In this neighbourhood of Princetown walls of well-trimmed ashlar have been erected by convict labour. A “transition” wall that is often found upon the borders of the moor is based upon a turfy ridge. Other walls may not unfrequently be met with which resemble the “dykes” of Cumberland, and are formed by loosely piling layers of small stones one above another. Of this last variety let the pedestrian beware the passage, unless he can find a gap made by some friendly sheep; for even should he escape ruining a large segment of the wall, he is sure to bring the topmost stones rattling about his heels. To any of these kinds of wall it would be difficult to assign an approximate date, and especially so if the chronologist were not versed with the unwritten history of each location. The Dartmoor wall presents a face on which, for several reasons, it is not easy to decipher the marks of years. The granite varies remarkably in quality; in one place it is extremely friable, in another it has the hardness of a gem. It is often weathered and overgrown, when used; and even when it is hewn raw from the quarry the peculiar climate of Dartmoor soon gives an aspect of antiquity. The continual moisture encourages the growth of mosses, lichens, and other plants, and soon subdues the exterior of the newest wall to a venerable complexion. Yet these two things at least are clear: namely, that wire fences are a modern abomination; and that there is probability that a good many of the older walls of the Dartmoor Forest date from the days of James I, when a fillip was given to improvements by the granting of definite leases for the first time and the creation of a greater certainty of tenure. An interest attaches to other walls, for the most part in ruin, because they mark the settlements of the “tinners” who were once so numerous. There will be a shattered gable near, and the traces of a little garden plot; and such remains give a touch of extreme melancholy to certain tracts of the great rolling waste.

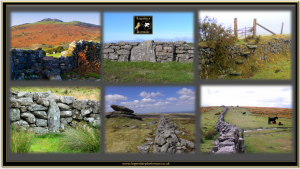

the Dartmoor wall is a microcosm of the moor; with its ruggedness, its wildness, its weirdness of colour, and its nooks of luxuriant growth. And, artificial though it be, it is in perfect accord with its natural surroundings. The curlew and the plover are everywhere about these quiet heights; but they are only denizens; the wall is a very part the mighty bulk of Dartmoor itself. But, putting fancies aside, it is the vegetation pranking our wall that makes it a wayside poem for the foot traveller. The shelves, the bosses, the crannies are overgrown with a rich variety of plants. A myriad of mosses are green upon it. The slow growing lichens, precious in pre-aniline days, touch it with sober hues. In the highest parts of the moor it may be diapered by the Arctic Gyrophore, survivors of the age when an ice-sheet partially clothed these uplands. The false maidenhair grows upon it in extraordinary abundance, and half a dozen other kinds of fern flourish about its loose knit rampart. Where a “wee burnie” half runs, half oozes through between the stones, a royal fern may be seen royally waving in the breeze. The “penny-hat,” (pennywort) is another familiar, and its creamy crockets of blossom are plentiful in June. Nor is it rare to find the clustered doves and graceful foliage of columbine or sweet blue eye of the wild alkanet. The Dartmoor wall supports specimens, in short, of the entire flora of the district, from the tall flap-a-dock (foxglove) to the stone crops and the minute geraniums that are the hyssops of southern Devon.

Nor does this exhaust the virtues of the Dartmoor wall. You may surprise a beauteous snake sunning upon it; or you may find a moorman there taking one of the long series of Devonshire meals – “stay a bit and breakfast, ammot and dinner, Mumpit and crumpet, and a bit of supper.” He will be no true Devonian if he does not offer you a draught of his cider; after which you may lie down upon your wall (there are many proper for that purpose), and dream of the dread Gubbins of “Dartymoor” who ate a baby with onion sauce. And what can be pleasanter than with half-shut eyes to look upon the solemn slopes of the mid-moor, the stern barrenness pointed here and there with rock; to follow a wooded gorge, fold after fold, till a plain glimmers grey across its mouth; or, half-dozing in the glare of the afternoon to listen to the moorland rivers “crying” down their glens?” – The Star, July 10th, 1884.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor