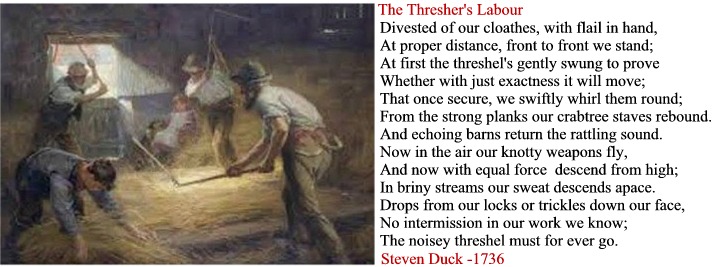

Before the days of modern machines and before the days of the steam engines one of the onerous processes of the harvest was separating the grains of corn from the husks, AKA ‘Chaff’. There were two ways of achieving this, either by threshing or winnowing. Threshing is officially defined as; “to remove the seeds of crop plants by hitting them, using either a machine of by hand,” and winnowing as; “to blow the chaff (the outer coverings) from grain before it can be used for food.” Both operations were very labour intensive and back-breaking work, especially threshing.

In his book of 1858 Samuel Rowe wrote the following: “The ‘flail’ with its monotonous strokes, still resounds from the barn floors of all our smaller farms, where economy or attachment to old usages, has prevented the introduction of the modern threshing machine. Still more rarely is the old method of winnowing resorted to; but in a few instances the ‘Windstone’ may yet be seen, where the process is accomplished by simple manual labour, – the grain being subjected to the action of the wind, on some elevated spot, and passed through sieves, shaken by the hand, until clean provender is produced… In this primitive process, the memory of the method of separating the grain from the chaff, so common in our county, forty years ago, (before the introduction of the winnowing machine,) is still preserved. In Devonshire, the hand threshing instrument is not known by the name of flail. Our vernacular retains the old Saxon word Therscol, by metathesis Threshel, and the aspirate ‘th’ changed into ‘d’, makes it ‘dreshel’.” – p.111.

In 1869, under the heading of ‘The Devon Labourer’ the following was noted; “The familiar sound of the flail is now seldom heard, but we are surprised in the most secluded situations by the smoke and whirr of the steam engine threshing the corn in the fields.” – The Western Times, September 17th, 1869.

In Smiles’ 1867 book – The Life Thomas Telford in regards to Dartmoor he wrote; “… the flail, with its monotonous strokes, resounds from the barn floors; the corn is sifted by the windstow – the wind merely blowing away the chaff from the grain when shaken out of sieves by the motion of the hand on some elevated spot…” – p. 111.

As can be gathered from the above lines threshing corn with a dreshel was hot, dusty, tiring and time-consuming work. In 1821 a young Devonshire man was said to have threshed with a dreshel 21 bushels and 1 peck of wheat in nine and a half hours. He began a-swingin’ at six in the morning and finished at a quarter to four in the afternoon. To give some idea of his accomplishment 1 imperial bushel is equal to 36.36 kilograms, so times by 21 – 0.76356 tonnes. Probably the most hated times for threshing with a flail were when the corn was damp and the atmosphere moist as this made it difficult to separate the corn from the chaff. In the February of 1846 the agricultural report for South Devon stated that; “The flail has been much in requisition, but owing to the dampness of the corn, in consequence of the humidity of the atmosphere, the work of the thresher has been ‘spare and painful,’ with a deficiency of the yield.” – Western Times, February 14th, 1846. Many authors refer to the ‘monotonous sound of the flail‘ and back then it must have been an everyday sound of the farm at threshing times. However, imagine hearing that rhythmic and nostalgic sound today compared to the continuous hum of today’s modern combine harvesters at work.

The Dreshel – Although seemingly a very basic tool it did have its component parts. In the Catholicon Anglicum of 1483 theses were listed as; “Tres Tribili partes, nanutentum, cappa flagellum, a swewille, Quo fruges iactantur.” In more recent times a dreshel comprised of; a ‘Hand Stave‘ of hazel (on Dartmoor the favoured wood was pine or ash) which was three feet and nine inches long. The ‘Horn Cable‘ which comprised of a ram’s horn fastened to the head of the stave forming a revolving loop at the end. Then the ‘Middle Beam binder‘ which was made from raw horse hide, one end passing through a slit in the opposite end and fastened with a peg. Next came the ‘Flesh Cable,’ again made of a horse hide thong which was attached through holes in the dreshel thus forming a loop which matched the loop on the hand stave. The ‘Middle Beam‘ would then be passed through these forming a double joint. Last came the actual ‘Flail‘ which preferably was made from holly wood measuring two feet seven inches long and two inches by one and a half inches thick. It was slightly flattened and the narrow sides had to be true as that it may fall evenly on one or the other of these sides. As you can imagine over time the flail would become pitted and worn so it was important to keep it smooth and evenly balanced, this would be achieved by the regular sanding, a process known as ‘keppeling‘.

In the ‘Complete Farmer’ of 1807 there are guidelines for dreshel threshers; “It is suggested that the tool (dreshel) by which this sort of business is performed should be well adopted to the size and strength of the person who makes use of it, as when disproportionately heavy in that part which acts on the grain, it much sooner fatigues the labourer, without any advantage being gained in the beating out of the grain… In threshing most sorts of corn, but particularly wheat, the operators should wear thin light shoes, in order to avoid bruising the grains as much as possible. In the execution of the work, when the corn is bound into sheaves, it is usual for the threshers to begin at the ear-ends and proceed regularly to the others, then turning the sheaves in a quick manner by means of the flail, to proceed in the same way with the other side, thus finishing the work.” It was also noted that in colder weather the downward thrust of the dreshel must be a lot harder than in dry conditions. With regards to the number of threshers needed on the threshing floor the book recommends either one or two, if however there are more it could lead to: “frequent interruptions and a consequence loss of time.” On Dartmoor wheat straw was widely used in thatching roofs and ricks and so was a valuable part of the corn harvest. Therefore when threshing with a flail the object, as Marshall stated was; “to extract the grain from the ear, with the least possible injury to the straw. To this end, the ears are thrashed lightly with the flail.” – p.181. He then went on to add; “It is not for the purpose of thatch, only, that the straw of wheat is carefully preserved from the action of the flail; but for the purpose of litter also; it being found to last or wear much longer, in this capacity, than softly bruised straw; which may be said to be already on the road to decay, and to have passed the first stage towards the dunghill.” – p.183.

Clearly a working rhythm would be vital especially when there were two or more operators to avoid flail clashes or worse, these was achieved by each thresher alternating blows of their dreshels. Again, referring to the West of Devon, Marshall suggested that; “This animating practice is sometimes extended to four thrashers working in the same barn; performing a peal, which, though monotonous, is not displeasing to the ear.” – p.184. It was also said that it was possible to tell what kind of paid work was being done by the speed of the ‘peal’, if the threshers were being paid a daily rate it would be much slower than those being paid for piecework.

The actual threshing floor was; “often made of oak planks. The floor was sited between two openings within the threshing barn where the through-draft could take away the chaff as the threshing took place.” Wood, p.168.

Flails were also used in harvesting grass seeds for re-sowing. The dry, cut Italian Rye Gross would be mowed and be tied into three foot long sheaves. Coarse cotton sheets were then laid down in the field and the sheaves placed on them and very lightly tapped with a flail. It was said that two men and a boy could thrash three acres of seed in a day by using this method.

Winnowing – As mentioned, one winnowing process simply involved standing on an exposed platform and continually shaking the winnow basket up and down and then allowing the wind to blow away the chaff. The Old English word for ‘winnow’ is windwian and from that such platforms have evolved as various names, ie. Windstone, Windstow and Windstrew. On Dartmoor there is a remaining Windstrew at the old manor of Longstone which sits beside Burrator reservoir. This is a granite faced platform measuring six metres long and five and a half metres wide and one and a half metres tall. There are three mounting steps on which one of them has the initials I. E AND J. E. incised with a date of 1637. The initials refer to members of the one time owners of the manor – the Elford Family. This is certainly the best example to be found so far on Dartmoor, other possible candidates being at Whittenknowle Rocks, on Royal Hill and Hook-in-Tor Farm,

The operator would simply stand on the platform and casting the grain into the air from the winnowing basket the only draw-back to this method was you needed at very least a gentle breeze and a dry day. In 1796 writing about West Devonshire agricultural practices Marshall said; “Farmers of every class (some few excepted) carry their corn into the field, on horseback, perhaps a quarter of a mile, from the barn, to the summit of some airy swell; where it is winnowed, by women! the mistress of the farm, perhaps, being exposed, in the severest weather, to the cutting winds of winter, in this slavish, and truly barbarous employment.” – p.184.

Another method of winnowing would take place in a barn and involved placing a large winnow sheet on the threshing floor and then by using a winnowing shovel simply tossing the grain into the air and allowing the heavier grains to collect on the sheet. A similar method was to use a ‘shaul‘ which was a thick length of preferably beech wood that had been hollowed out to make a three-sided tray which tapered to a narrow lip. This would be held in both hands and then scooping up the grain and tossing it into the air in the normal manner. With both these methods a winnowing fan may be used to create a draft of air. Simple forms of these were simply made from woven basket work whilst a more mechanical version entailed nailing several sheets of canvas to a spindle which was mounted in a frame and turning a handle, thus creating a draft of air.

As noted above, gradually these early methods of threshing grain and seeds became mechanised, initially powered by turning a handle but then steam powered engines replaced those. For the smaller Dartmoor farms the march of progress took a lot longer to come into being, mostly due to affordability. It was around the early 1800s when adverts began to appear in the local Devonshire papers advertising threshing and winnowing machines for sale, usually at farm auctions. The first advertisement that I have come across for a threshing machine for auction in the Dartmoor area was in 1820 for a sale at Lower Pound farm, Buckland Monochorum.

There are several old sayings that relate to threshing such as; “fly like chaff from a threshing floor.” or “whisked about like a thresher’s flail.” and “rise from the flail,” – the condition of threshed corn. There is a toast used at agricultural dinners and meetings which goes; “Success to the plough, The fleece and the flail, May the landlord ever flourish, And the tenant never fail.“

Marshall, W. 1796. The Rural Economy of the West of England. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

Rowe, S. 1856. A Perambulation of Dartmoor. Plymouth: C. E. Moat.

Smiles, S. 1867. The Life of Thomas Telford. London: John Murray.

Wood, S. 2003 Dartmoor Farm. Tiverton: Halsgrove Publishing.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

I’m writing a book about 3 generations of my paternal ancestors who were farmers in Kent. I love the illustration of threshers on this page. Could you tell me who the artist is?