“Fire sent forth great clouds of smoke upon the waste, wind running ripples of flame crept along before the wind. Behind them extended a gloomy mantle of ash and char; before them streamed their banners of smoke. These spring fires, or “swaleings,” had been deliberately lighted that furze and heather might perish, and the grasses, thus relieved, prosper for flocks and herds.”- Eden Phillpotts, pp. 256-257.

Swaling or ‘Swealing’ in the Dartmoor vernacular – sounds like some sort of manic folk dance, but it is a practice that has been carried out for thousands of years. also later prosaically termed – ‘March of the Fire Festivals of the Moorlands’. Evidence from various peat analysis on Dartmoor has found microscopic charcoal dating back to Mesolithic times thus suggesting that people were using fire to improve environments for attracting game.

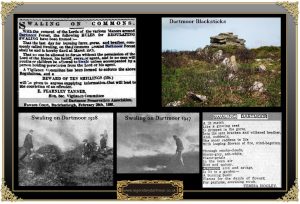

Today swaling is the annual burning of the gorse and scrub in order to thin out the old vegetation in order to allow new grass shoots to grow thus providing grazing for the livestock. The first recorded instance of the word ‘swaling’ comes from a poem written in around 1205 AD by Layamon called Brut, it is suggested that the actual word comes from the Anglo Saxon word – Swælan meaning to burn. A statute dating back to the late 1600s stated that; “To burn on any waste between Candlemas (Feb. 2nd) and Midsummer, any grig, ling, heath and furze, gorse or fern is punishable with whipping and confinement to the house of correction.”

There were some strange beliefs associated with swaling, for instance in the 17th century it was thought that by setting fire to the moorland vegetation would make it rain. So deep seated was this idea that when King Charles was due to visit and area he would write to the High Sheriff forbidding that any fires should be lit on common land. This was because he was; “desirous that the county and himself may enjoy fair weather as long as he remains in those parts.” In seasons when the hay harvest was poor and the hay itself very expensive farmers would take advantage of the young gorse by cutting it into chaff, something that would be impossible without swaling. Other later reasons for swaling were to allow the commoners their right to gathering ‘black stick’ – pieces of burnt wood that would be collected into faggots and taken away for use on the home fires (see photo below). This was usually a chore that the children were expected to do. It was also thought that by burning the vegetation it would also destroy any snakes that may be harboured within it. The famous herbalist Culpepper noted that; “Fern being burnt, the smoke thereof driveth away serpents, gnats and other noisome creatures.” When a moorman was questioned as to the excuse for burning gorse brakes he indignantly replied; “Ah, but think of the varmint it a ‘arboured!”. Swaling was also thought to be a way of controlling any local fox populations which in a way was slightly wrong as during swaling it spoilt many a days foxhunt. One early drawback to swaling concerns the sheep flocks that graze swaled land, soot from the charred gorse sticks to the natural oil in their fleeces turning them almost black in colour., which meant lower prices for the fleeces. I don’t know if you have ever seen such sheep but they are a weird sight and in some cases the Scotch sheep take on the appearance of Herdwicks.

In 1808, Vancouver regards swaling or burning to be, “a safe and effectual means of bringing coarse moory land, when effectually drained, into a state of profitable cultivation ...” Swaling would occur on the commons and wastes of the moor, and as stated above the idea was to burn off the old growth and allow new shoots to establish thus giving some good grazing. In addition the wood ash would also act as a fertiliser which in turn would encourage good regrowth. An article noted that; “Time was when the public were expected to take their part in swaling, possibly as some little return for the freedom of the moor which they enjoy. Notices are still issued here and there on the Moor stating that from such and such a date swaling is permitted for three ensuing days. It would seem that anybody during that period may set fire to the gorse. But when the three days has expired it is an offence to create a fire on the moor.” – The Western Evening Herald, March 31st, 1923. As you can imagine such a practice was not only chaotic but also haphazard and in some cases caused a considerable amount of damage to the moorland landscape and wildlife. By the mid 1800s Dartmoor was fast becoming a much appreciated landscape where many people came to enjoy the freedom and beauty of the place. Around this time loud voices were beginning to be heard complaining about the unregulated swaling practices. In 1861 the Malicious Damage Act came into force and it stated that; “Whosoever shall unlawfully and maliciously set fire to any crop of hay, grass, grain, or pulse or to any cultivated vegetable produce, whether standing or cut down, or to any heath, gorse, furze, or ferns, wheresoever the same may be growing, is felony” In effect this could be applied if so wished to swaling but was seldom if ever brought into force.

In 1883 the Dartmoor Preservation Association was formed to protect the moor from the various threats to its very fabric. One of these concerns was the uncontrolled practices of swaling and the damage it was causing. In the January of 1888 Mr. Fernley Tanner, the Honourable Secretary of the Dartmoor Preservation Association wrote in a letter; “The approach of the swaling season summons me to take steps to carry out the desires of so many lovers of picturesque moorland, so I appeal to you, sir, to allow me to make a public request that the Vigilance Committee many be invested with powers by the various owners of the manors comprising of commons, to act on their behalf in prosecuting those found setting fire to furze, gorse or heather, holding no authority from the lawful owners so to act.” – Western Morning News, January 14th. This request was granted by several of the relevant Lord’s of the Manors and a notice appeared in the Western Morning News on March 2nd 1888 setting out the rules and regulations for swaling (see below), it also offered a ten shillings reward to anyone offering information that led to a conviction of an offender. Despite these measures there seemed to be little advancement in the controlling of swaling. At the Proceedings of the Devonshire Association in 1895 the Rev. Baring Gould raised his strong concerns that no effective measures had been taken to stop the indiscriminate swaling on Dartmoor. In 1902 a letter appeared in the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette which bemoaned the fact that; “It is stated that a reasonable amount of the burning is legitimate until the end of March… Last week I had the occasion to drive from Okehampton some miles over the moor through Belstone, and, to my dismay, found we could scarcely recognise the place. Excepting on the left-hand side of the river, which is, I understand, chiefly private property, the beautiful Cleave is an unsightly mass of blackened and charred stumps… Indeed the evening I passed through Belstone there were no fewer than five distinct fires in the Cleave alone, and at the present moment the banks of the Taw from Skaigh to Sticklepath are merely charcoal.” – May 23rd, 1902. In 1903 the parish of Whitchurch were allowing swaling from the 1st to the 31st of March at the same time there was great concern that on Blackdown it was children who were lighting the swaling fires. In the same year it was the hunting fraternity that were issuing concerns about swaling as in the case of hares the fires drove them away from where the hunts were active. In 1906 swaling fires set alight by children on Brent Hill and parts of the Carew estate destroyed some of the preserves for foxes thus curtailing the Dartmoor Hunt’s activities. Swaling has also be blamed for the drastic decline in the Moor’s grouse populations as it was said to have destroyed their nesting places and in some cases their eggs.

In 1909 two men, Mr. F. B. Mildmay and Mr. J. Woolacombe met with representatives of the Duchy of Cornwall. The purpose of the meeting was to present a large petition requesting that the Duchy regulated swaling and prevented unauthorised swaling – little change was effected.

In 1927 the famous Dartmoor authoress Beatrice Chase entered into the anti-swaling affray, in a letter she commented that; “On Easter Monday, long before noon, our sun was put out by smoke. At 2.30 I went to the top of Widdecombe Hill, and for an hour and a half watched men, women and children setting fire to the moor with petrol. Peaceful holiday makers who had brought lunch and were trying to picnic were invisible in clouds of smoke. When the motor-coaches arrived from the lowlands, and the conductors endeavoured as usual to point out the beauty spots there were none to be seen. Widdecombe valley was enshrouded in a dense smoke screen”. So serious was the swaling problem becoming that plain clothed policemen were sent up to the moor on motorcycles in an effort to catch offenders lighting illegal fires. As they could only use the roads it was impossible to catch anyone in the cat of lighting fires into the moor.

In the August of that year the Chief Constable of Devon requested of the County Council that a bye-law be introduced which prohibited the swaling on common etc after a certain date, except when the weather prevented swaling earlier. The Duchy of Cornwall was quite willing to accept this resolution on their lands. The matter was then left for the Devon County Council to consider what action should be taken and in the end the bye-law was passed that swaling should only take place during March. In order to enforce the ruling many noticeboards were erected around the moor warning unauthorised people of the penalties of lighting illegal fires.

In 1928 another noted Dartmoor author, Douglas St. Ledger Gordon wrote the following; “It is disappointing that the efforts made by Devon County Council to repress indiscriminate burning have not received the support they deserve… For some uncountable reason, however, the Westcountryman appears to possess at best an hearty idea of that principle, and is not content whilst a single green shoot shows above the surface of the moorland. Instead of confining his activities to the old and worthless growth he cannot resist applying an indiscriminate match to anything he thinks will burn, irrespective and apparently unconscious of the fact that more often than not he is merely destroying valuable pasturage and so injuring himself and all concerned. The satisfaction afforded him by the sight of the smoke and the blaze make ample atonement from his point of view from any loss that he may inflict upon his self and others.”

Despite the threat of conviction in 1929 many illegal swaling fires were still being lit, especially on Sundays and early closing days by townsfolk and locals alike who were visiting the moor, much to the annoyance of other moor folk, many of which heartily accepted the new regulations. In 1939 illegal fires were still common practice and again St. Ledger Gordon noted that; “The heath conflagrations are practically without exception the work of local hands, mainly village children and youths who spend Sunday afternoons at this time of year in what they are pleased to term ‘swaling’. This consists of children running from one gorse bush to another with a box of matches, and youths and young couples strolling upon the commons starting a fire or two by way of adding excitement to a ‘dull’ walk.” – The Western Morning News, April 9th, 1939. In this year also the swaling notices posted around the Moor had an additional restriction insomuch as; “All Fires must be extinguished before sunset in accordance with the Emergency Powers (Defence) Regulations, 1939, and the Orders made there under.”

At Tavistock Court a tourist from London appeared to answer the charge of ‘Illegal Swaling’, he was observed doing so on Hangingstone Hill, the charge was brought by the Duchy of Cornwall. It was stated that; “In the old times, perhaps, such an act was not so serious, but now that hundreds of visitors visit the moors, it becomes a very serious matter, because for the past four or five years the summer tourists have been doing an immense amount of damage. At that time the sentence for ‘Malicious Damage’ was a fine of £5 or imprisonment, in this case the defendant was fined £1 6s 6d and costs.

During the Second World War

In 1948 Penelope Seaman wrote the following; “Every year in early Spring swaling is carried out on the moors, the farmers burning the old gorse and heather to clear and refresh the ground. Unfortunately it is a great temptation for small boys also to light their little fires, and some parts of the moor have been overburnt, with the result that only clumps of turf remain instead of the great thick stretches of heather to which the Dartmoor addict was accustomed. It is a fascinating sight to watch this process of purification by fire, whose beginnings stretch back into the early days of time. As you walk over the great hills, a column of smoke rises like some giant waterspout, wreathing upward in the wind then sweeping low over the ground.

On reaching its source, you find a fire, an oasis of light in the wide wilderness of green and brown. Bright streaming caverns of flame fall into enchanting pergolas and curving bowers where the Greek muses might well have composed their songs of beauty, First you see a sun-bright garden in the wind, then the flames leap, fall on a fresh tuft of grass, flicker, flare up; and behind is left a grey ruin, a pale pattern of fragile remnants of fern. So the crimson snake creeps along the ground till exhausted. Then the crackling ends, the smoke ceases to blow bitterness into the eyes, and a hush falls upon the land, broken only by the high larks fluttering and carolling tirelessly. Thenext day, this patch of moorland will greet you with a rich warm peaty smell redolent of things to come. Brown as a chestnut, it will be bared to the life-drawing rays of the sun; and many days later, strong bright spears of grass will be thrown up to protect the surrounding land.” – Widecombe Ways, pp.IX, X.

When swaling is taking place the huge plumes of smoke can be seen from many a mile, in the past I have seen the far horizons glowing from the fires which is hell of a sight. As can be seen from the picture above it does not take long for the new shoots of grass to establish themselves amongst the charred remnants of the gorse. These days the practice of swaling is strictly regulated and controlled as can be seen from the following guidelines issued by the Dartmoor National Park Authority and DEFRA:

The burning, not only of heather and grass, but also gorse, bracken and bilberry, is controlled by the Heather and Grass, etc (Burning) Regulations 1986.

Before burning you must telephone; 1) Devon and Cornwall Fire and Rescue Service, 2)Dartmoor National Park Authority, 3) Natural England and 4) The Dartmoor Commoners Council.

1) Burning is only allowed between: 1 October – 15 April in upland areas. The National Park Authority recommends no burning after 31 March to prevent harm to nesting birds. Outside these dates burning is allowed only under licence issued by the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA).

2) Permission of the owner must be gained.

3) At least 24 hours but no more than 7 days notice of intent to burn must be given in writing to the owners and occupiers of the land concerned and persons in charge of adjacent land.

4) You must not start burning heather, grass, gorse, bracken or bilberry between sunset and sunrise.

5) You must ensure that sufficient people and equipment are on hand to control the burn.

6) You must take all reasonable precautions to prevent injury or damage.

7) You must not cause a nuisance through the creation of smoke. This is an offence under the Clean Air Act 1956.

8) You must contact English Nature if burning on a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

9)Under the Dartmoor Commoners’ Council’s Regulations, arising from the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985, no person or local Commoners’ Association shall burn moorland where heather is present on the commons exceeding an area of 9000 square metre at intervals of less than 12 years, nor where the distance between burns in any one year is less than 150 metres.

10) No Person or local Commoners’ Association shall burn moorland where dead grass, bracken or gorse is present on any common land unit exceeding 50 acres (20 hectares) or 25% of the area of that common land unit which ever shall be the less and such burning shall take place at intervals of no less than 3 years.

Prosecution:

A breach of the Heather and Grass, etc (Burning) Regulations 1986 may on conviction result in a fine of up to £1,000

For SSSIs failure to give written notice to English Nature can result in a fine of up to £2,500 under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

As can be seen, the above hardly gives anyone the inspiration to go swaling yet on the other hand numerous bodies are de-crying the amount of gorse and bracken now colonising the moor. As you can see swaling has for centuries been a very emotive subject and in many cases still is today. On one hand you get people voicing their concerns with regards to wildlife and on the other the graziers who pasture livestock on the commons needing vital forage to graze, of which there can be no question. During the swaling season there are always a large number of photographs appearing on various social media platforms of the swaling fires, most of which attract many ‘likes’ and appreciative comments. Although in recent years there have been several large moorland fires these have been suspected as cases of arson not official swaling.

Phillpotts, E. 1902. The River. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co.

Phillpotts, E. 1902. The River. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co.

Seaman, P. 1948. Widecombe Ways. London; The Saint Catherine Press.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Last year I discovered 3 species of Butterflies on Roborough down that although in small numbers were there and just hanging on.

1. Green Hairstreaks in the Gorse

2 Pearl bordered Fritillary nectaring on gorse and bramble blossom

3.Small Heath nectaring on ground bugle.

After the long winter I could not wait to start searching for them again in the late Spring of this New year of 2018.

Yesterday I went to survey the site, just to see, and recall the locations in readiness for my 2018 survey.

To my absolute dismay I found the whole site had been extensively Swaled , it looked like a totally devastated black landscape as far as the eye could see.

My horror and concern now is were the eggs, caterpillars or Larvae of these wonderful butterflies destroyed in the inferno, and if there will be any bramble and gorse blossom, and ground Bugle reappearing in their feeding months of May and June ?

At the moment I am in complete shock.