Now and again whilst thumbing through various Dartmoor books one will come across a brief mention of the moss gatherers of the early 1900s. There can be no question as to the vast supply of sphagnum moss on Dartmoor even though it is said to be decreasing today. Very little has been recorded of their activities apart from the fact that the moss was used as wound dressings during the First World War. I had been unable to discover how it was processed, how much was used etc. That is until I stumbled across the following article which explains in detail how the moss was gathered and processed:

“Quiet but busy men and women are doing good things in the heart of Dartmoor. For Princetown is the headquarters of the sphagnum moss work in the West, and from this grey village, 1,500 feet above the sea, among the tors, there weekly depart to the Midlands, to the West and South, and overseas, a hundred sacks of dried moss and 500 prepared dressings, ready for immediate hospital service. Often knee-deep in the great bogs and mires for miles round a man, who has devoted himself to the work, labours daily in the fair and foul weather. Nearly 5,000 sacks has this devoted worker collected since last spring, and his masses of material come from the moor up to an asphalt lawn-tennis court at Princetown, where the officers of the convict prisons took recreation in pre-war times. Here men and women spread and turn the masses of the moss day by day, and their difficulties are great in wet weeks, for sphagnum is the most absorbent of vegetable things, and this surgical virtue means that one storm of rain will waste a week of sunshine. But it reaches a good measure of dryness at last, and is then carried to the depot – a house of many rooms hard by, taken for the purpose, sweet with whitewash and antiseptics, heated by hot air from a furnace, and full of women clad and capped in spotless white. The moss has shed its lustre now, the ivory and green and gold have faded, and it is reduced to the colour of hay. Here it is spread on a grille above a system of hot-water pipes, and rendered until crisp and springy. Thus perfected, it is dispatched to the hospitals for further treatment; but the depot is not content with being the largest centre for distribution in England; dressings are also made, and the laborious treatment of the moss followed in every particular until the finished dressings have been completed. Three hours careful work go to each. The moss is first picked over, and every shred passes through a woman’s fingers, to remove grass and twigs and the thousand fragments from the heath buried in its soft masses. The pure stuff is now ready for the dressings, and two ounces of moss go to each little, flat muslin bag, 10 inches by 14. They are then passed through a solution of corrosive sublimate (a refining or purifying substance) by a worker in rubber gloves, squeezed through a little mangle, and dried again, that they may return to the specified weight, for after the bath they are two ounces too heavy. Now, perfected, the dressings are made into packets of a dozen each, and wrapped in two papers; finally, for overseas, they are packed into bales of a hundred dressings covered with waterproof sheeting through which no germ can penetrate. Thus they depart by the thousand, and the cry is still for more. Every facility is here, and, thanks to the Prince of Wales, all things necessary for the work have been found. The workers only are lacking, and if a few shell-shocked soldiers are other willing hands could be found to assist the present overworked and too scanty staff of volunteers, much would be gained. Let active, elderly men who sigh for an opportunity to serve, come to Princetown. Before November a harvest must be garnered sufficient to meet potential needs until the spring – a task only certain of accomplishment given sufficient aid. Half a dozen men capable of daily, easy work would end the anxieties of the present staff and ensure the vital needs of the Red Cross until another spring. In addition to extraordinary absorbent qualities – a two ounce dressing will absorb up to two pounds – sphagnum has its own antiseptic virtues. It contains iodine, and has been proved of the utmost hospital value, answering every test.” The Times Tuesday, Sep 03, 1918; pg. 9; Issue 41885; col. E

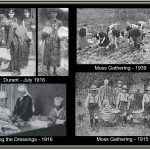

The moss factory received a visit from the Prince of Wales on the 23rd of February 1918, the following report appeared in The Times newspaper: ‘The Prince visited the sphagnum moss depot, which he has not only provided and equipped, but maintains at his own expense. Here he met Mrs. Read, who is in charge of other workers, who number about 40. Each department was inspected, and the various processes were explained to the Prince, who keenly sought information, and wrung out moss-dressing saturated with sublimate. Mrs. Read referred to the excellent facilities for the treatment of the moss, and the Prince expressed pleasure that what he had done had met with approval.’ The Times, Saturday, Feb 23, 1918; pg. 3; Issue 41721; col. C At Mary Tavy there was a collection point for the sphagnum moss, here it was raked into heaps, dried, cleaned, sorted and put into baskets for delivery to the depot. One Mrs Groser was not only the manager at this collection point but it also appears the Transport Manager. Clearly there needed to be a way of getting the moss to the depot and her solution was to acquire a donkey and cart for this purpose. At Widecombe-in-the-Moor is an old navy shell which was presented to the villagers by the National War Savings Committee, on it is a plaque which reads – “This 15″ Naval Shell was presented by the National War Savings Committee in 1920 to the people of Widecombe in recognition of their efforts during the First World War gathering Sphagnum Moss for use in the treatment of wounds“. In 1917 the Tavistock Urban Council gave the use of the old Towers Butchers Market to the Red Cross as a collection point for the moss. It was said that at times there would be; “seventy five square yards of moss spread on the benches waiting to be cleaned.” In 1916 a newspaper report detailed the exploits of a Mr. Durant, a retired wool merchant from Okehampton who it was aid had tramped over a 1,000 miles on Dartmoor collecting the moss, valued then at £75. Apparently he would be out in all weathers with his adapted moss-rake in all weathers, on some occasions scraping away the snow in order to get to the moss. He would then transport the moss some 25 miles to the collection depot at Exeter

After the war the Disposal Board of the Ministry of Munitions announced that they had a stock of 350 tons of sphagnum moss for sale, (The Times, Saturday, Jun 14, 1919; pg. 9; Issue 42126; col. D). In 1940 once again the plea for moss gatherers was published, this time it went to any scouts or guides who were camping out in moorland areas. Later in the same year it was reported that school children from Devon had spent their summer holidays collecting seven boxes of sphagnum moss for the war effort. At the end of World War Two the woman in charge of the Irish sphagnum collection, Mrs Alice Henry was awarded an O.B.E. for her efforts it was deemed that important. In 1919 it was reported that the Exmouth Sphagnum Moss Depot contributed £28 13s 10d to The Times fund for the Red Cross and St. John’s Ambulance Brigade. The use of sphagnum moss for wound dressings is no modern discovery, there are several prehistoric burial sites where the moss has been discovered next to bodies. In one example at Ashgrove (Fife) the moss was found amongst the remains which showed evidence of a chest wound, archaeologists at the time suggested that it had been used as a wound dressing. It has been suggested that man first became aware of the medicinal properties of sphagnum moss when they observed wounded animals rolling in it. The Vikings were known to have used sphagnum moss as an early form of toilet paper, other uses included nappies and sanitary towel substitutes. The German Army was the first to re-invent the sphagnum moss wound dressing, a move that was quickly adopted by the British Forces as noted above. Some people have suggested that due to its water retaining properties and lack of combustibility sphagnum moss was used to stop up cracks in cottage chimneys. Another common use is/was as a packing for hanging baskets, as a base for potted plants and in wreath making There are 12 different species of sphagnum mosses occurring on Dartmoor, all of which range between a red to green colour. Each type tends to colonise differing areas of soil acidity and moisture content.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

My Great Grandmother Fanny Frances Howell is the tall thin lady 4th from right back row in cutters & machinists photo!

Colette Grace

Hi Colette – I’m writing about how this moss was used as dressings in the war and I’d love to chat to you about your great grandmother. Pls could you email me anna@environmentaljournalist.co.uk ? thank you