When walking on Dartmoor it won’t take very long to come across a leat, in the modern landscape it may appear as a gently flowing channel of water or simply as a shallow, dry ditch. Nobody to my knowledge has been brave enough to estimate the miles of leats that exist on the moor and I too am not going to follow suit. Needless to say if all the leats were taken into account they must run for hundreds of miles. But what exactly is a leat and why is it so called? The word leat comes from the Old English word – wætergelæt which literally means: ‘water channel’, (ODEE, 2008, on-line source). As the advert goes: ‘it does exactly what it says on the tin‘, or in other words a leat is a man-made water channel. The nearest surviving example of the Old English word wætergelæt is in the Dartmoor place-names of Waterleat Bridge, Waterleat Farm and Waterleat Wood which is just north of Ashburton. The word leat is often pronounced on the moor at ‘late‘ which can cause a certain amount of confusion.

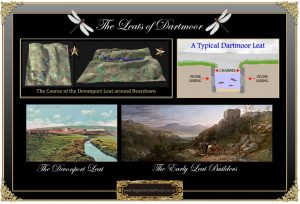

The leats were designed to carry water, by means of gravity, from its point of extraction on a natural water course to its destination. Once there, the water would be used for a whole host industrial, agricultural and domestic purposes. The art of the leat builders was a skilled job as they had to ensure the flow of water was not too fast so as to flood and not to slow as to stagnate. This was achieved by ensuring the leat followed the natural contours of the landscape which in effect reduced the force of gravity enough to allow for a gentle and manageable flow of water. In many cases so subtle was the gradient of the leat that the water they carry can appear to be flowing uphill. A good example of how a leat contours around a hill can be seen on the eastern flank of Beardown where the Devonport Leat flows down towards Plymouth, a section of which can be seen below:

Where the direction flow or volume flow needed to be controlled this was done by a variety of sluice gates and weirs and in some cases a leat-feature known as a ‘bullseye stone’. Every leat will have its extraction point on a watercourse albeit a river, stream or brook and from here the water will be directed to where its needed. The early leats which date back to medieval times were in effect a power supply for the tin industry. It was water power that drove the early stamps which were used to crush the tin ore and also powered the bellows used to heat up the smelting furnaces. These early blowing houses usually sourced their water as close as possible to the blowing house and therefore the leats were often quite short in length. But in later centuries some of the tin mines such as Wheal Jewell on the northern moor sourced their water supply from a considerable distance which meant a long system of leats. Leats also provided water to power water wheels in corn mills and fulling mills used by the wool industry. In places such as the Finch Foundry at Sticklepath the water powered the bellows, trip hammer and grinder used for the production of tools. At Powder Mills leats were used to bring water which in turn powered the crushers which processed the raw materials needed for the manufacture of gunpowder.

If a leat was supplying water to a farm or homestead then on Dartmoor it’s known as a ‘Pot Water Leat’ and once there it would have provided drinking water for both human and beast, washing and cooking water. In addition the water was often used to keep certain types of produce fresh, at the old Hentor farm a granite trough was placed in the flow of the leat and was used to keep the cream cool, hence its name – the ‘Hentor Cooler’.

Some of the early moorland towns and villages received their domestic water supply via a leat which often terminated at a dip trough for collection. Sometimes this type of leat is referred to as a ‘gutter’ as in Holne Town Gutter, King’s Gutter, Elbow Gutter and Tor Gutter.

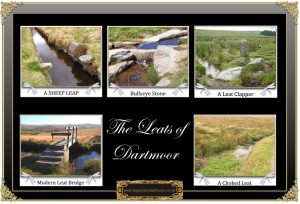

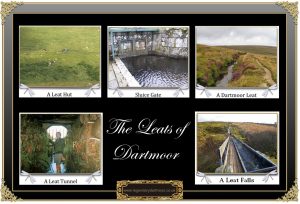

There are several features which are associated with leats that can still be found on the moor today. My favourite is the ‘sheep leap’ which consists of two projecting slabs of granite, each one set adjacent into the opposing banks and protruding about a foot over the leat. Their purpose in effect is to assist a sheep when it jumps the leat by providing a launch and landing pad thus reducing the risk of it falling into the water and becoming trapped – see illustration below. Another feature, although not so common as the sheep leap is the ‘bullseye stone’, the best example of which can be found near to the Windy Post. This particular example is even recorded on the 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey map (SX 53445 74298 – English Heritage Pastscape Record – HERE). A bullseye stone is a flat slab of granite with a central hole bored through it that has been set into the main wall of a leat. Its purpose is to act as a kind of sluice that will maintain an optimum supply of water to a subsidiary leat – see illustration below. Another common feature that is associated with leats is the granite clapper bridge which can often be seen spanning the leat channels of both dry and full leats. These can vary from one small span to four or five which would make it large enough to carry a pony and cart across – see illustration below. If a leat ran through a rabbit warren the warreners would often put a single slab of granite across the channel to allow the rabbits to cross. Some of the larger leats such as the Devonport Leat were driven through hillsides by means of a tunnel, an example of which can be seen near Nun’s Cross Farm – see illustration below. Incidentally, it is not advised to enter these tunnels as they are private property and more importantly dangerous, do as I say not as I do? Other features associated with leats are weirs, sluice gates, the occasional workers hut and modern footbridges of various types. On the side of Gibbet Hill is a leat that once supplied some mine workings, after use the water was returned to the River Tavy by means of a deep channel known by the splendid name of ‘The Gurgy’, (Crossing, 1990, p.159). Another Dartmoor oddity was a small porcelain disc with a Turk’s Head on it that was embedded into the wall of the Devonport Leat, know locally as either ‘The Turk’s Head or ‘The Indian’s Head‘, folks could not decide which it was meant to be.

The expertise of the men who surveyed the leats must not be underestimated as the skill in finding the right contours and gradients was vital. The Dartmoor leats can vary from a narrow channel about three foot wide to the larger ones that can be around ten feet wide. The major leats were constructed by digging a channel and banking up its sides with the spoil, in more recent times the main leats had the sides of their channels lined with granite stones to ensure there was no slippage of the bank. Over time vegetation such as grasses and heather took root on the banks which had the effect of strengthening the sides:

One of the more famous leats on Dartmoor is ‘Drake’s Leat’ in 1591, its purpose was to deliver drinking water to the rapidly expanding population of Plymouth. The course of this leat was about 18.5 miles long and from the intake point on the River Meavy it gradually descended from 675 feet to sea level at its destination which was Sutton Pool in Plymouth, (Hawkings, 1987, pp. 7 – 8). During the early 1800s the dockyard at Plymouth was becoming busier and needed a bigger water supply however the good folk of Plymouth refused to share any of theirs. So in 1801 the Devonport Leat was opened to satisfy this demand. The leat extracted water from three take-off sources; the West dart, the Cowsic and the Blackabrook and originally ran for 28 miles from the moor to Devonport.

Today on Dartmoor there are eight main leats which still have water flowing along them; The Grimstone and Sortridge leat, Wheal Friendship leat, Wheal Jewell leat, Hamlyn’s leat, Holne Town Gutter, Gidleigh Leat and the Devonport leat. The waters of the Devonport leat are currently used to feed into the Dousland water treatment works, indeed, the local water authority are licensed to take out 2,727 Ml/yr.

There were several drawbacks with using leats to convey water. Firstly, when relying on vital water supplies it was always a problem in harsh winters when they froze up especially if they were carrying water for domestic use. On the 22nd of January of 1881 severe weather froze the Devonport Leat which meant that Devonport was virtually without water until gangs of men could clear the leat. So serious was the situation that the Water Works Company posted the following notices; “So long as the dearth of water continues, every economy must be observed in the bedrooms. At tea etc., not more than two cups can be allowed. In the house every care must be taken that not one drop be wasted. Any extravagances proved, the party so wasting will be fined sixpence, and the money given to the Poor Relief Fund. When the stand pipes are giving a supply the porters must at once procure a sufficient quantity for the day’s supply, or they also will have to pay a like fine.” Similarly in the March of 1909 the Devonport leat froze solid from between Dousland and it’s take off point under Longaford Tor. It was reported that over 50 men were employed with clearing the least of ice and snow. However, so severe was the weather that all the progress made each day refroze again at night. Secondly, it was difficult to keep them pollution free as there was always the danger of contamination from such things as dead animals etc. The leat used to bring water into Dartmoor Prison was built below a channel that carried sewage away from the building which surely meant a risk of pollution. The biggest draw back to a moorland leat is erosion and leakage, very often you can see on a hillside a bright green patch of vegetation spreading downhill. This is normally a featherbed of moss forming in a wet area where the leat has breached its banks and is leaking downhill. It does not take long for leats to become clogged up with water weeds which again could inhibit the natural flow – see illustration below. Therefore in order to maintain and clear the leats it was necessary to employ men to regularly inspect the channels and clean or repair them when necessary. Leats can also prove a danger to livestock, especially sheep because if one should fall in then the steepness of their sides and the extra weight added by a water-logged fleece can make it impossible for them to climb out. On two occasions I have come across a sheep that has become trapped in the channel and believe me it’s not easy to lift a heavy, saturated and struggling ewe back onto the bank.

For the modern day rambler the beauty of a leat is that by following its course you are guaranteed a gentle walk no matter whether you travel up or downstream. Indeed, for anyone interested in leats and walking their courses there are two books that have been written on the subject. The first one is now out of print but often available from second-hand book shops, it was written by John Robins and is called ‘Follow the Leat‘. The second book was written by Eric Hemery and is entitled, ‘Walking the Dartmoor Waterways’ and both books give a detailed description of the main leats and how to follow them. Mind you if they have water in them it’s not that difficult.

Crossing, W. 1990. Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor. Newton Abbot: Peninsula Press.

Hawkings, D. J. 1987. Water from the Moor. Exeter: Devon Books.

Hoad, T. F. (ed.) 1996. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Online source at:

http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t27.e8598

Further Reading.

Hemery, E. 1991. Walking the Dartmoor Waterways. Newton Abbot: Peninsula Press.

Robbins, J. A. C. 1984. Follow the Leat. Privately published by J. A. C. Robbins.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Hi,

Fantastic website you have. Full of information supported by references and sources

Hamlyn’s Leat is no longer running from the lower head weir on Holy Brook (728678). The sluice gate is shut and, in any case, there is insufficient water in the brook to approach the sluice gate. At the lower (Buckast) end the leat is silted up and sluice gates shut. No water is flowing into the launder/water wheel at the back of the former plating works currently being converted into something else.

Further to my earlier post about Hamlyn’s Leat (referred to as Holne Moor Leat on the OS maps), I can report that it is flowing strongly across Holne Moor when viewed on 16 Aug 2016- even after a prolonged dry spell in late summer. At the point where it discharges into the Great Combe branch of the Holy Brook at 692697 (former channel completely dry), it forms a mini waterfall; without it this branch of the Holy Brook would be dry in its upper reaches, at least in summer. So Hamlyn’s decision to build the leat 150 years + continues to be the correct one even if the water is no longer needed to power mill waterwheels downstream.

A further book, 128 pages, by John Robins is ‘Rambling On’ published in 1988. With plenty of photos and diagrams, it’s a follow-on from ‘Follow the Leat’ and is full of facts and explanations about Dartmoor leats not found anywhere else. Part 2 is entitled ‘Walks of Investigation’ and successfully challenges many of Hemery’s previously authoritative statements about some of the disused leats covered in his books.

For people who enjoy exploring remote leats and the seldom-visited countryside along their routes, the book provides many days of fresh discoveries. If you are lucky enough to spot a copy in second hand book shop, snap it up as it went out of print years ago.

Any time I need to research an aspect of Dartmoor I consult the informative and innovative pages of “Legendary Dartmoor”. There is so much more information on these pages, including quirky bits that cannot be found elsewhere on the Web.

The leats are a fascinating subject in and of themselves and I look forward to getting deeper into them: if you’ll excuse the pun.

Many thanks, Tim, for taking the time and trouble to write about beautiful Dartymoor.

Best wishes – Mike Tucker, Liverton

Thanks Mike, kind thoughts indeed.

Thank you for all your work in producing this website. We set off for a short walk today and spotted an aqueduct on the OS map while heading towards what we now know is Windy Cross. Turning left we followed the watercourse and found the timber aqueduct, then kept going as far as Merrivale where private land and “Keep Out” notices stopped us. Wanting to know what we had seen I came across this site which is by far the best source I have found. We are keeping our boat in Sutton Harbour for a year and will be using Legendary Dartmoor to keep us informed from now on!

Is it possible/allowed to canoe some of these leats?

NO!!!