One thing Dartmoor is not short of is walls and another thing is stone with which to build them, there must be literally hundreds of miles of walling across the moor. It is also surprising how deep into remote areas the walls extend and are a true testament to the wall builders resolve. The first job the early Dartmoor farmers had to do was enclose his land and that meant building sturdy walls around enclosures known as ‘newtakes’. One of the rights of an Ancient Tenement (farm) holder was that on succession of the farm the son could enclose a further 8 acres of land excluding rock and bog. During the 1700’s the So called improvers abused this right so much that it was rescinded in 1796. Many would enclose vast tracts of land under the pretext that much of it consisted of rocks and/or bogs.

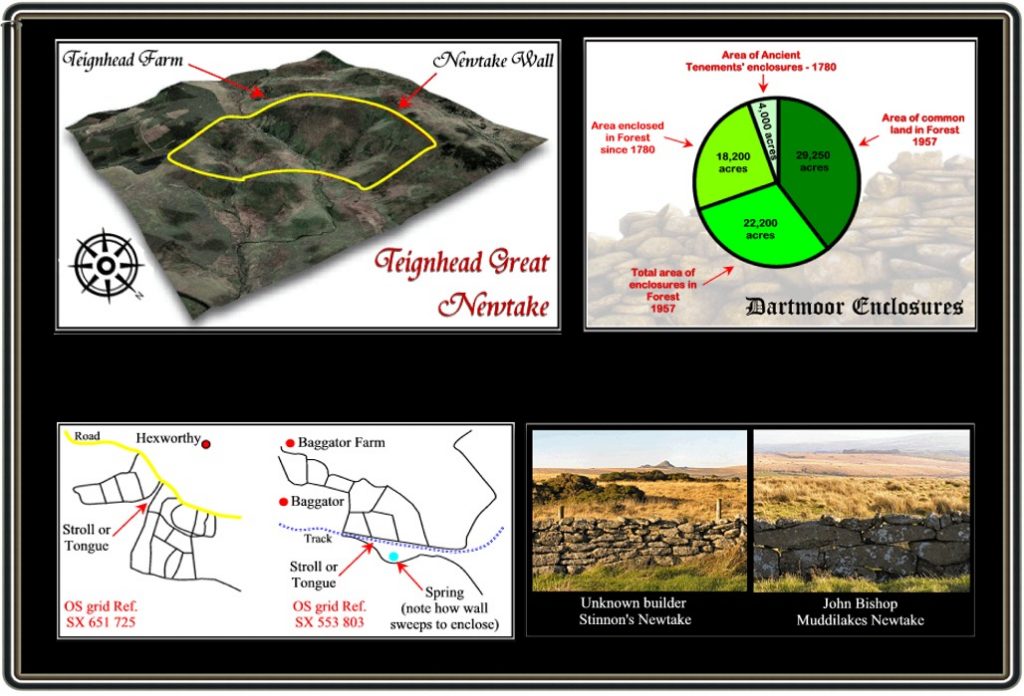

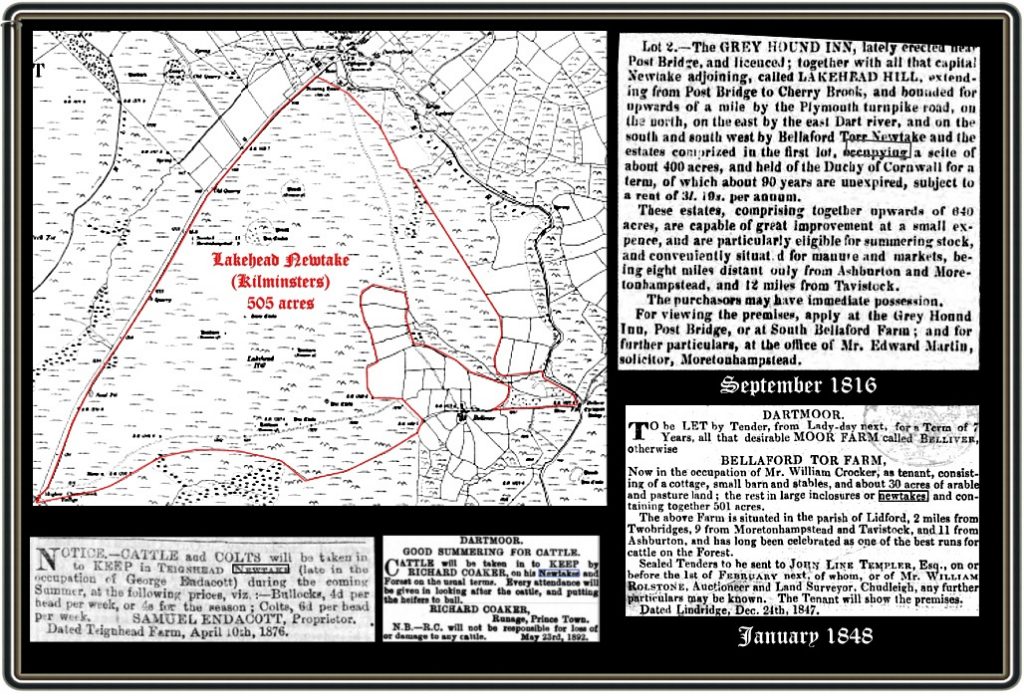

The 3D aerial map below shows the Teignhead Great Newtake which was enclosed during the early 1800’s. The wall around the enclosure is 4 miles (6.43km) long and as can be seen from the map crosses some very steep and remote areas. Other examples of a large newtakes were that of Lakehead newtake which encompassed some 505 acres and Bellaford (Bellever) at 501 acres.

During the late 18th century and early 19th century many acres of commoners’ land was enclosed under licence from the Duchy and understandably this made the ‘improvers’ very unpopular with the moorfolk. Writing in 1877 one author noted that; “We cross the West Dart and are onto Swincombe and note the new enclosures going on towards Tor Royal. There are extensive plans for a long distance here which are easily fenced into suitable fields…” The Tavistock Gazette, March 9th. In the March of 1880 the Tavistock Gazette carried an advert for someone looking to rent a well-fenced newtake consisting of anything between 100 and 1,000 acres unfortunately there was no reason why. In 1889 the effect of the enclosures was described by one author that; “This custom accounts for the numerous enclosed and small cultivated spots found on all parts of the moor. The effect has been to take away the best parts of the pasturage of the moor,leaving only the worst for the venville men and their ponies. The Duchy have themselves within the last hundred years permitted large tracts of the valleys and best sheltered land to be enclosed by private person, which has led to the destruction of thousands of ponies from the want of shelter they formerly had in the snug combes around the moor.” – The Western Times, January 4th, 1889. It was no unheard of for some landowners to build a newtake at a short distance from any others. Then when the chance arose they would simply co-join it to the rest thus quietly getting more land without any objection. This is why sometimes solitary newtakes can be seen which seem to have no obvious connection. There have also been cases where attempts to build newtakes have been met with local discontent as it was seen as stealing common land, two such famous examples being the Irishman’s Wall and the stand-off near South Zeal. These latter day newtakes were in utter contradiction to the old Forest customs and chart below shows some statistics on the enclosure acreages of Dartmoor.

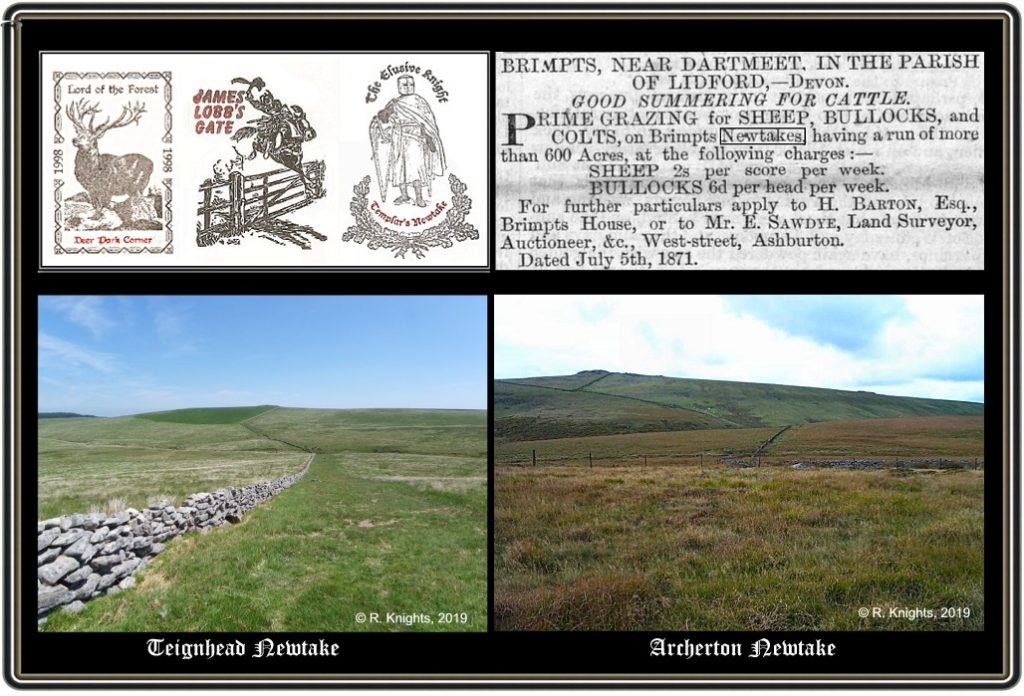

So having established the need for enclosure walls there then came a need for people to build them and a good ‘Waller’ was worth his weight in gold. The newtake walls were built by piling stones to a height of between 4 and 5 feet and in some instances even higher. No mortar was used for binding and all was down to the skill of the builder. The materials for building walls was normally near at hand in the form of the moorstone or in many cases recycled stones from ancient monuments. Probably one of the most infamous case being that of the prehistoric double stone row which ran southwards from the Longstone to a trio of blocking stones known as the ‘Three Boys’, two of these stones were removed to provide gateposts for the Thornworthy Newtake. One author wrote: “… withstood the even more ‘reckless moods’ of those ignorant beings who have for modern newtake walls, or houses, removed without thought so many of the most interesting relics of antiquity.” – M. S. Gibbons, 1886, We Donkeys’ on Dartmoor. Another prime example of recycling monuments is the partially finished cross that is incorporated in the newtake wall nnw of Laughter Tor In the early days the wall builder would never break or shape the stones used in building the wall. When the available stones were large the wall would be solid but where the materials were smaller the result would be a less substantial enclosure where “daylight could be seen through,” them. In situations where there was not a convenient supply of stone it would be brought to the site by means of sleds drawn by ponies. In later years many of the wall builders started using only the large stones which were roughly squared or dressed. The discarded smaller stones would be gathered into heaps and left in the newtakes and today are classifies as ‘clearance cairns’. Another way the discarded stones were utilised was to build them into the corners of the enclosures which in some cases resulted in them being up to five or six feet wide. When the course of a wall met an obstacle such as a large boulder the builder had two options, he could either build it into the wall or deviate around it, many newtake walls show examples of both such features. Sometimes if you look down the length of a wall it will be seen that it suddenly make a semi-circular sweep and then return to the original straight course. This was done to encompass a spring into the newtake which would provide a water source for the livestock. On the edges of the moor, some of the walls will make a large sweep into the newtake thus forming a semi-circular bowl sometimes known as ‘courts’ or ‘telling places’. The purpose of this was to allow the farmer to gather his cattle or ponies so they could be counted.In some places, usually on the edge of the moor the walls can be seen to gently taper towards a gate. These are known as ‘strolls’ or ‘tongues’ and were used as a funnel to gather livestock (see below). When driving animals, they hate to be suddenly bunched so a stroll allowed them to be gradually and gently driven into a group. The strolls also provided shelter in bad weather and accessible feeding points in wintertime. There are many examples of walls that abruptly finish with for no obvious reason and this is because either money ran out or the enclosure was deemed as being nonviable, these are often called ‘Walls End’. Every newtake has a name with some of them having early Celt or Saxon derivations. The majority of names are called after their respective farms or holdings such as Beardown Newtake, Baggator Newtake, Blackaton Newtake etc. Some take the name of owners or lessees like Chaffe’s Newatke, Hamlyn’s Newtake, Joan Ford’s Newtake, Sawdye’s Newtake, Tucketts, Newtake etc. In some cases the word newtake has been added to an existing landscape feature, ie, ‘Newtake Hill’. One of the best sources to find the names of Dartmoor’s newtakes are the hunting reports which appeared weekly in the local papers many of which have not been recorded elsewhere. Not only do the individual newtakes have names but very often so do the gates in their walls and some of the corners formed by them. The names often refer to the land owners, enclosure builders or newtake uses such as ‘Deer Park Corner’, James Lobb’s gate’ and Templar’s Newtake. Many of these gates served as access points known as hunting gates for the various hunts which ran through many of the newtakes.

As can be seen below from just a very small selection of local newspaper adverts some newtake owners would let them out for summer grazing to lowland farmers. This was another annual source of income and as can be seen below in 1871 the owner of the Brimpts 600 care newtake was charging two shilling a score for sheep per week and six pence per head of cattle per week. In 1876 George Endacott was charging summered bullocks at four pence a head per week or four shillings for the season and six pence a head for colts at Teignhead newtake. In 1901 Rider Haggard stated that; “there are stretches of enclosed land called ‘newtakes’ which are not so valuable as they used to be, but still bring in a rental from £30 to £100 according to their size. The letting value of pure moorland, by the way, appears to be from 4d to 6d an acre.” – The Torquay Times, May 24th, 1901.

There were several advantages to grazing livestock in newtakes for example, providing the walls were maintained it is a lot easier to contain and look after the animals as opposed to the free ranging ones on the open moor. Additionally at times of contagious disease outbreaks which demanded movement restrictions it was a lot easier to contain the beasts in a newtake. In 1871 such a movement order was put in place during an outbreak of Foot and Mouth disease whereby anyone moving or allowing animals to be moved would be prosecuted. But there were also disadvantages to grazing livestock in newtakes such as ensuring the walls were maintained to prevent animals from straying. In the smaller newtakes the animals would be fairly well confined which meant if someone wanted to steal them they were easily accessible. The local newspapers are full of adverts offering rewards for’ lost’ or stolen cattle, sheep and ponies. In 1877 two sheep went missing from Archerton newtake (see photo below) and the notice read; “Whoever will give information of the same to Wm Coaker, if stolen shall on conviction of the offender or offenders shall receive the above award, (£5) if strayed, all reasonable expenses will be paid.” In 1886 poor Mr. Coaker had lost another three sheep, this time from the Stannon newtake however his notice read the same as the earlier one except this time the reward for catching the offenders had risen to £10. In 1895 45 sheep were driven into the river Swincombe whilst grazing in Fox Tor newtake by a ‘suspicious-looking dog’ of some kind, thirteen of the sheep were found with their heads partially chewed off. – Western Morning News, December the 4th, 1895

Over the years there have been many court cases involving newtakes in one way or another. In 1873 Lydford farmer named Coaker appeared before the Tavistock Highway Board to present them with a claim for thirteen pound and five shillings. At the time he was renting a newtake at Powder Mills on which he was taking in bullocks for summer grazing. At the time there was an unfenced quarry in the newtake into which a bullock fell and died the result of which was that the farmer only received five pounds for the carcass. The board upheld the claim and ordered the money to be paid by Lydford Parish and that the surveyor ensured that all unfenced quarries were enclosed. In 1909 at Tavistock County Court William Coaker who farmed at Nun’s Cross Farm claimed £10 from Mr. A. Willcocks the owner of Fox Tor Newtake for not maintaining the fences around his enclosure thus allowing his sheep to enter. Willcocks deemed that the sheep had entered his enclosure unlawfully and so drove the 42 sheep to Dunnabridge Pound which meant the farmer had to pay to have them released. It was suggested that the Duchy Steward, Mr. Barrington, visit the enclosure to ascertain if the fences were not maintained and after his inspection he deemed they were in a fit state of repair. He also added that the sheep in question were of the Scotch Blackface breed and very few walls would stop them from entering. It took over a year for the case to come to a conclusion and the verdict was found for Willcocks.

In the December of 1910 Coaker lodged an appeal against the findings and the case was heard at the King’s Bench Divisional Court. In a nutshell the judges decided that as Barrington’s clearly stated the fences were in good repair and that Scotch Sheep were renown for being able to jump three feet higher that the local sheep breeds. Therefore whilst the owner of a newtake was bound to fence against sheep he was not obliged to cater for the ‘wandering disposition’ and ‘jumping addiction’ of the Scotch breed. The appeal was dismissed along with the incurred costs but leave was granted for further appeal. In the February of 1914 there was the sad and mysterious case of William Donaghy whose body was found in one of the Hartland newtakes by two local farmers, the full story can be found – HERE.

In the August of 1921 an 89 year old man from Tavistock was tending some sheep in a newtake beside the railway running from Mary Tavy to Tavistock. Sadly the old gent was deaf and did not hear an approaching train whilst he was crossing the track unfortunately the driver was unable to stop in time and he was killed on the spot. In the March of 1925 the foreman of the Duchy estates Mr. Frank May was charged at the Tavistock Petty Sessions with causing necessary suffering to three ponies which were placed in the Muddylakes newtake on the Novemeber of 1924 and under the charge of George Coaker. Coaker stated that he lodged the animals there as a favour but also that he had told May that they would not survive the winter there and that they would need some feed.

In the January of 1925 he informed May that he had better move the ponies and a few days later he found one of them dead. the court found May guilty and fined him £3 and 31 10s. costs. They also added that they were not satisfied with Coaker’s conduct and that he should have found out their condition earlier. In the August of 1928 a farmer from Cheriton Bishop appeared before Moretonhampstead Petty Sessions charged with failing to remove his 156 sheep from Gidleigh Moor in accordance with the ‘Sheep Dipping and Movement of Sheep Regulations’. The whole idea of this being that all sheep were removed from the moor and under supervision dipped in order to prevent the spread of the contagious Sheep Scab. In this case the farmer was found guilty and as a warning to others was fined £20 which in terms of today’s value would have been over £1,200.

In 1930 the Forestry Commission along with the approval of the Duchy of Cornwall Council announced plans to plant over 5,000 acres of their lands with trees which included many newtakes around the intended areas. Naturally many locals who grazed these newtakes along with other concerned bodies were outraged. The eminent Dartmoor author and historian R. H. Worth prepared a report in which he stated; “The agricultural standpoint is worthy of consideration. The newtakes when given to the foresters will also be a loss to agriculture. the one excuse for maintaining the newtake walls was the grazing value of the land. This is to be sacrificed, and it means a loss to agricultural Devon. The afforestation scheme will certainly not pay Paul, but it will rob Peter.” – The Western Morning News, October 2nd, 1930. As is known today the Duchy went ahead with their plans and if you visit any of the main areas or look at any modern map that were afforested – Bellever, Fernworthy and Soussons you will still find or see remnants of the old newtake walls. Similar outcry’s were made regarding the loss of grazing in the newtakes lost due to the development of the various Dartmoor reservoirs such as Fernworthy, Burrator, etc.

In 1934 there was some lively debate in the letters section as to the keeping of bulls in the newtakes, one author expressed his concern as to the effect this had on tourism by writing; “I could name several newtakes in which one could find bulls, all dangerous brutes. I remember your report of the Rent Audit Dinner of the Duchy of Cornwall of 1932 at Princetown, at which the Duchy Secretary proposed the toast of ‘Prosperity to Dartmoor’ and spoke of the good time the tenants were to have by taking in paying guests. Now a large number of the would-be visitors to Dartmoor are horrified to come, as they are faced with bulls.” – The Western Morning News, August 20th, 1934.

Probably the most noted Dartmoor newtake wall builder was John Bishop of Swincombe whose work is easily distinguishable from that of other builders (see photo above) and much of which exists today. He always maintained that any wall he built was “ordained to stand,” and the reason being was that he was one of the first to use the large, shaped and squared stone building method. John always used large, tightly fitted blocks of granite through which very little ‘daylight’ could be seen. When once asked how he managed to move such heavy granite stones he replied, “Aw, ’tis surprisin’ what ee can do with a laiver or two.” Which meant some of his essential tools were crowbars or as he called them, “bar ires.” Bishop was one of the builders that always used a pony and sled to carry any stone. He was full of praise for his pony and it has been recorded that he always maintained that the pony “belonged to vayther, an wudden no more’n vourteen, or vourteen an’ a half, an’ I’ve a zeed’n shift a stone up dree tin (ton) wight ‘pon a sled.” Below are two examples of newtake walls and it is not hard to distinguish the large slab work of John Bishop. John Bishop was born in 1821 and if the 1851 census is correct he and his wife had their first child at the ages of 14?. In the 1851 census his occupation was described as ‘labourer’ and they were living at Cherberton (Sherberton). The ruins of his house still stand today beside the Swincombe river and whether this too is a reminder of his building skills is unknown. John Bishop died in 1892 at the age of 71, although long gone his work still encloses many newtakes on the moor and act as a tribute to a true craftsman. He was known as the type of man who would not suffer fools gladly and who intensely hated being watched whilst working. It was said that if anybody did he would stop work, fill his pipe and stand in silence until the offending spectator had retired. He despised modernisation and always stuck to the traditional ways, he was famed for continuing to use a steel and flint lighter long after matches had become the norm. His work was legendary and his skills were always in demand but if any employer dared to criticise his labours or suggest other ways of doing he would find himself blacklisted for any future work – sounds my type of man. There is one story about how he an two friends were accused of poaching hares on Duchy land and as a result John was given notice to, “determine his tenancy.” Bishop clearly had friends in high places because the upshot of the matter was that the Duchy Steward, Charles Barrington, received a strongly worded letter from the Duchy Secretary in London which suggested that the accuracy of the allegation was dubious to say the least.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor