Allspice, Barum Beauty, Beech Bearer, Beef Apple, Bickington Grey, Billy Down Pippin, Bowden’s Seedling, Brown’s Apple, Butterbox, Devon Crimson, Devonshire Redstreake, Devonshire Striped, Devonshire Whitesour, Docker’s Devonshire, Ellis Bitter, Endsleigh Beauty, Fair Maid of Devon, Farmer’s Glory, Golden Bittersweet, Hollow Core, Johnny Voun, Limberland, Listener, Lucombe’s Pine, Lucombe’s Seedling, Malor, Michaelmas Stubbard, Morgan Sweet, No Pip, North Wood, Oaken Pin, Paignton Marigold, Peter Lock, Pig’s Snout, Plympton Pippin, Ponsford, Pyne’s Pearmaine, Quench, Red Ribbed Greening, Royal Somerset, Slack Ma Girdle, Star of Devon, Stockbearer, Sugar Bush, Sweet Alford, Sweet Coppin, Tom Potter, Trimlett’s Bitter, Upton Pyne, Veitch’s Perfection, Whitesour, Woodbine, Woolbrook Pippin and Woolbrook Russet…..

These are some of the varieties of apples grown in Devon, many of which were used for cider making. As you can see from the list, apples were taken very seriously and nowhere more so than on Dartmoor. There is an old quote regarding Devonshire men and cider, Marshall, 1970, p.237: “Their orchards might well be styled their temples and apple trees their idols of worship.”

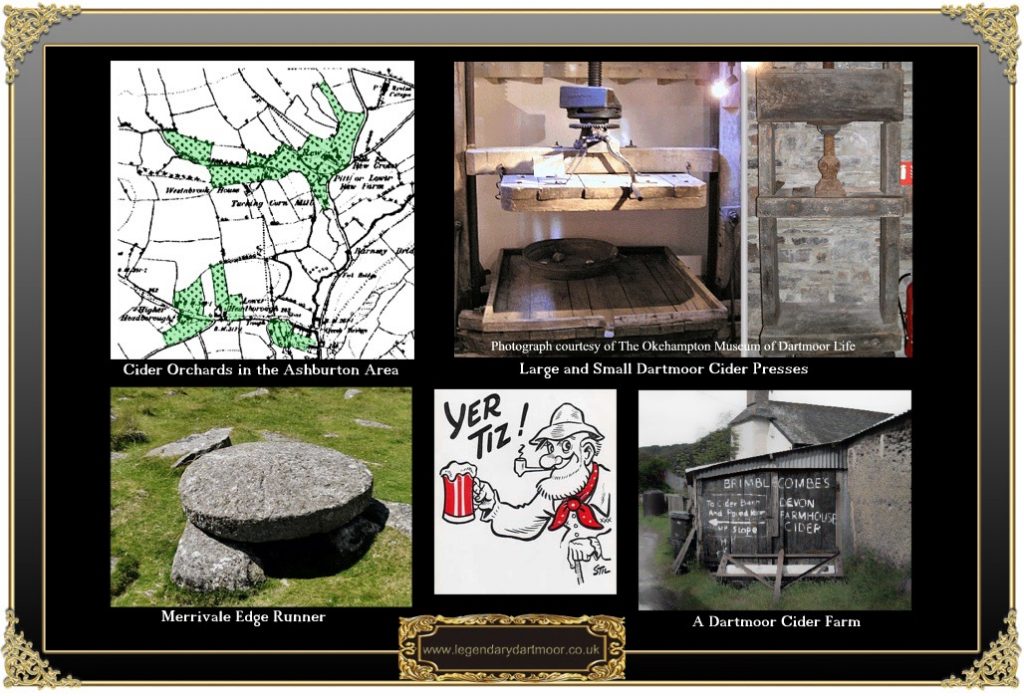

It can generally be assumed that by the 13th century cider making had come to Devon. One of the early records of Tavistock Abbey mentions that the Abbot had a cider press at Plymstock in the late 1400’s, and in 1475 four pipes (1 pipe = 126 gallons) of cider were brewed from apples grown in the Abbot’s orchards, Finberg, 1969, p.196. Cider making was at this time an important commodity brewed by the various monasteries around the moor. Worth, 1988, p.384, notes that at one time what was thought to be the largest pound-stone in Devon resided at Buckfast Abbey. He also notes that another pound-stone was to be found acting as a base for a fountain at Buckland Abbey, no such stone had been found at Tavistock Abbey. Supposedly, the best ‘monastic’ cider was produced at Buckfast Abbey although legend dictates that it was Tavistock Abbey which produced the ‘sweetest cider in Devon‘. It was not only the monasteries who at this time brewed cider, many manors and farmsteads were producing large quantities. The 1889 – 91 OS map extract below shows a very small area above Ashburton, you can clearly see from this small example the extent of orchards that occurred on the moorland fringes:

The traditional method of cider-making was described by Marshall, pp 224 – 232 as taking place in the ‘Pound House’, which he described as being: “generally a mean shed or hovel, without peculiarity of form, or any trace of contrivance. On the larger Bartons, or where the Orchard grounds are extensive, appropriate buildings are fitted up, in different ways“.

The apples would be harvested by gangs of men and women, the men would knock the fruit from the trees with long poles and the ladies would then gather up the apples in large wicker baskets. The apples were then left to mature in heaps either in the pound house or in the open air. Once the fruit had ‘come’ which was when the brown rot began to appear the apples were ‘broken’. This occurred in a variety of ways, on smaller farms the fruit would be placed into a large trough or tub and then pounded with large club shaped wooden pestles. These ‘clubs’ would have their heads studded with nails which made the grinding operation a bit easier. This process usually involved up to six people who all stood around the chosen receptacle. Larger farms and manors would use circular granite troughs to pulp the fruit. The apples would be placed in the trough and then a large circular, vertical stone would be ‘run’ around the trough thus pulping the fruit. In the very large operations the ‘runner’ stone would be wheeled around the trough by horse power, if the operation was smaller then the stone would be hand powered.

In both types of operation the resulting pulp or ‘pomage’ would then be pressed, this would be done between layers of reed (unthrashed straw) or straw in a perforated box upon which sat a heavy granite weight, this was known as a ‘cheese’. In some places a screw or lever press was used, the principle was the same but the weight instead of sitting on top of the press was actually ‘screwed’ or ‘levered’ down.

The ‘must’ or expressed liquor which trickles from the press would then run through a channel into a flat tub known as a ‘kieve’. The juice was then poured into a granite vat and left to ferment. During this process the many particles of dirt and debris would float to the top where it would be skimmed off. The liquid would then be ‘racked’ to complete fermentation, Vancouver, 1969, p240, states how if a lighted piece of cloth or paper that had been dipped in brimstone was pushed into the barrel bung it would stop the fermentation process. He also notes how if a candle burns clear when held up to the bung-hole it means the fermentation process is ‘easy’ or finished.

After the fermentation process had finished the liquid would be filtered to varying degrees and poured into wooden ‘hogsheads’ (63 gallons) or ‘pipes’ (126 gallons) to mature. Cecil Torr (1970, p.17) notes how if when full the cider casks are stood on end the top soon becomes dry and shrinks, this then lets in the air which spoils the cider. To this end many of the large cider producers would build large cellars for the barrels to lay on their sides thus keeping both ends wet and airtight. However, he came up with a method whereby he simply stood the barrels on their ends and filled the pan formed between the top end of the cask and the chine with water. Provided this was kept topped up the top of the barrel would not dry out.

Once mature the cider would then either be sold to towns and inns of the area or consumed on the farm. It was generally the larger farms and manors that sold the cider and generally in these cases the home cider would be made from windfall apples thus ensuring the better quality cider made a profit. Marshall notes that in the late 1790’s unfermented cider or ‘must’ would fetch around 15/- a hogshead and the fermented cider anything from 1 – 3 guineas an hogshead.

Over the centuries the cider making process went through many technical changes and continued well into the 20th century where on some farms it became almost a factory sized operation. Many of the notices of local farm sales included cider making equipment and sometimes actual hogsheads of cider.

Eventually farm-made cider began to decline and cider orchards disappear mostly due to the onset of large cider manufacturers who clearly could produce huge quantities in their factories. In many cases where farms once supplied their local inns and taverns with cider this business was lost to the large cider manufacturers many of whom would have contracts with the hostelries. The result being that the farms still produced their own cider but a much smaller scale than previously as it was only for their own consumption. However, in 1933 the demand for cider was beginning to outstrip production. This was mostly due to the lack of available cider apples and so to overcome the problem the cider manufacturers were offering farmers a three year scheme whereby they got one free cider apple tree for every ton of apples supplied to them. It was hoped that in that 1933 the scheme would enable an extra 10,000 to be planted and by the end of the three years this total would have risen to 30,000 new trees. This dearth of cider apples naturally led to a huge increase in their price. Between 1913 and 1917 cider apples were fetching around £1 15s. a ton, between 1926 and 1930 the price had risen to £4 11s. at ton and in 1931 the price had reached £6 5s. at ton. Sadly today there are very few if any Dartmoor farms producing cider and only a handful in the rest of Devon. A survey carried out in 1960 revealed that there were 780 cider orchards on Dartmoor, by 1965 321 of them had been destroyed and 46 remained in a ‘managed’ condition, Greeves, 2005, p.10. Below are listed the farms on Dartmoor who still produce cider: Brimblecombe’s Devon Farmhouse Cider, Farrant’s Farm, Dunsford. 2) Luscombe Cider, Luscombe Farm, Buckfastleigh. Such was the importance of the cider apple crop that local newspapers used to report the state of the crops and the outlook for cider making. In 1851 the Western Times reported that; “The demand for new cider has increased, and the price has advanced at from 22s. to 25s per hogshead.”

Farmhouse cider has always played an important role to many of the Dartmoor folk, it used to be said of Lustleigh men that they were more concerned with the prospects of the apple crop than in the corn crop. They would never be ‘happy boys’ until Ashburton fair day because by the first Thursday in June there was no longer the threat from frosts and the apple crop could be ensured. The other critical time for cider orchards was believed to be the ‘Franklin Nights, which were between the 19th and 21st of May. Again these were times when sharp frosts would damage the apple crop.

Once the farmhouse cider had been made it was stored in the ‘cider house’ which in some cases was not always the most secure location for it. This temptation at times proved too great for some folk who would steal it either for their own consumption or profit. If caught there could well be serious repercussions, in the March of 1832 two men, J. Baker, aged 21 and W. Sanders aged 25, appeared before the Devon General Sessions at Plymouth charged with such a crime – they were both found guilty and sentenced to 7 years transportation.

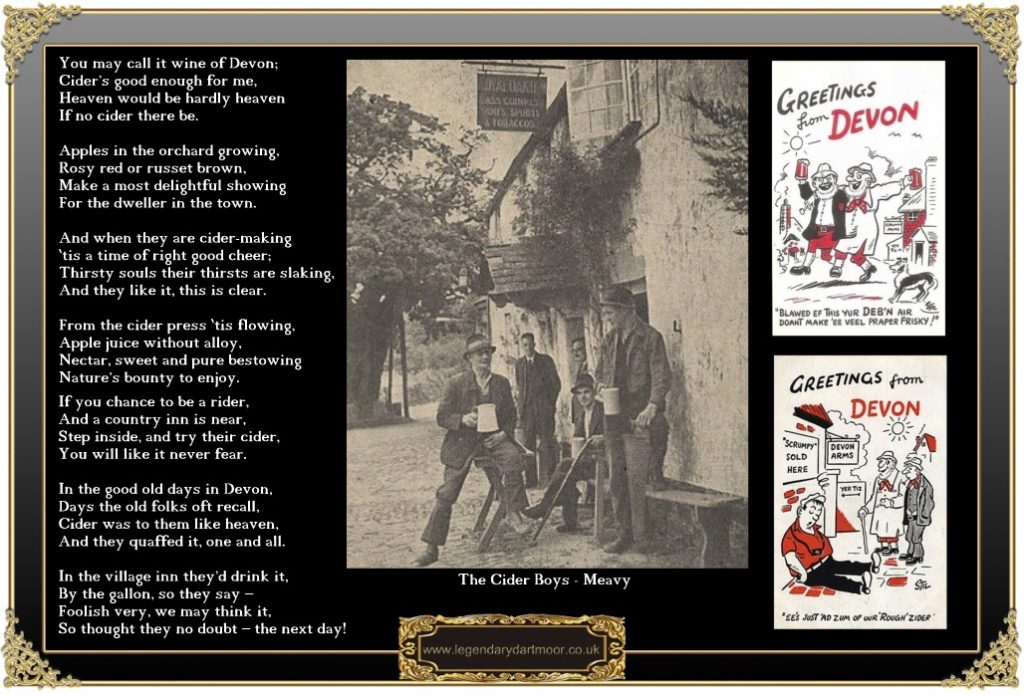

In many cases Cider was part of a labourers wages, It could be said that cider drinking became a serious problem and many a vicar or preacher would deliver long sermons about the ‘Devil’s brew’. Marshall, pp 233 -8, gives some very interesting observations on cider. He considers that: “The drunkenness, dissoluteness of manners, and the dishonesty of the lower classes might well be referred, in whole or in great part, to the baleful effects of cider; which workmen of every description make a merit of stealing: and what is noticeable, the effects of cider, on working people appears to be different from that of malt liquor. Give a Kentish man a pint of ale, and it seems to invigorate his whole frame: he falls to his work again, with redoubled spirit. But give a Devonshire man as much, or twice as much cider, and it appears to unbrace and relax, rather than to give cheerfulness and energy to his exertions“.

Taking the above comments to account it is slightly surprising that in the 18th century it was usual for a labourer to receive a daily winter allowance of 2 quarts of cider, this would rise to 3-4 quarts during haymaking. The cider was considered as ‘truck’ or part of the weekly wages. Agricultural labourers used to tote their cider around with them in a ‘cider flask’ or ‘firkin’ containing anything from a quart to a gallon which were either carried or fixed to a belt. When drinking cider at home or at the inn a large mug was required as can be seen from the photo below. One Dartmoor labourer was once asked how much cider he drank in a day, his reply was; “Well zur, I ‘as me a quart afore breakfust, an’ a quart wi me breakfust an another arter, The a quart wi’ me lunch an if we be ‘arvestin’ I rekons tu get droo ’bout vowerteen or saxteen quarts afore night.” Even in this toper’s paradise there were certain rules, a typical example being of the time when one Sunday morning a stranger knocked at a door begging for a drink of cider and was given short shrift by the maid. His response was, “You know not what you do. You might be entertaining angels unawares“. The reply soon came back, “Get the ‘long, angels don’t go drinkin’ cider church-times“. If you look at various magistrate court hearing reports from the mid 18002 to the 19130s you will see numerous Dartmoor folk being charged with being drunk and disorderly, sometimes in charge of a cart or wagon. It would be fair to say that the actual type of alcohol consumed is never mentioned at lost of it would have been cider.

Another problem with cider was that of ‘Devonshire Colic’, this was caused when the presses were lined or ‘caulked’ with lead which in effect gave rise to lead poisoning. Mind you, Marshall also notes that when inspecting some of the presses to see how much lead was used he came across one that was caulked with wool and cow dung. He also surmised that another contributing factor to ‘Devon Colic’ was a, “vile spirit”, drawn from the lees of the fermenting room. These dregs were distilled (illegally) twice through a porridge pot with a tin head that was attached to a hogshead of water. This brew was known as ‘necessity’ and at times was used to counter the effects of ordinary colic.

One very important ritual associated with the apple crop was ‘wassailing‘ the apple trees which still to this day can be seen in parts of Devon. Another tradition for Christmas time was the drinking of mulled cider, this was done by adding a pinch of cinnamon and a crab apple into a tankard of cider and then putting a hot poker into the drink.

At one time any farm business was usually carried out in the cider house, I can recall about 20 years ago when calling on farms the deal would be struck over a glass of cider. Depending on the variety of apples used the colour of the farmhouse cider would vary from light green to dark orange and after about 6 calls could vary immensely. I remember one farmer who told me the story of his new tractor. It appears that his farm needed a new tractor and after a great deal of research on his part the farmer had decided exactly what make and model he wanted. He phoned his local tractor dealer to ask a rep to call, in theory this would have been the easiest order to take as it was just a matter of the farmer signing the paperwork. The rep duly arrived on the farm and it did not take long for the farmer to realise that he came from ‘abroad’, or to quote, “bleddy Lundin”. As always the tractor salesman was invited into the cider house to clinch the deal over a ‘drap o’ cyder’. For some reason the rep refused the proffered mug of cider saying there was no way he was going to drink that crap as he had heard what it, “does to you”. Well, in this case what it did for him was to send him back down the farm track with an empty order book ,when, all for the sake of a slug of cider he could have been thousands of pounds better off.

Some farms will also feed the apple pomage or pulp to cattle and I remember visiting a farm one day and the farmer showing me a cow he thought had gone down with ‘mad cow disease’. The poor animal was just laid in its stall knocking its head against the wall. I was asked if I thought it was the dreaded disease and as I looked at the cow a smile broke across the farmers face. It was a wind up, as what happened was the previous night the farmers forgot to shut the gate behind which was the pile of apple pomage. The unfortunate cow had got in and gorged itself on the apples and was now suffering from a severe hangover.

But I have also seen the bad effects of constant cider drinking, there used to be two brothers who day in and day out would go down the pub for both morning and night sessions. One night they didn’t arrive and the ‘newsin’ soon got around that one had blown the other to pieces with a shotgun because he put on his brothers wellingtons. Sadly some of the most turbulent years I have known were when I was regularly drinking scrumpy cider. It seems to have the knack of turning normally quiet people into aggressive, raving lunatics – me included. They don’t say ‘cyderedup‘ up for nothing! I see that the recent trend is to drink bottles of chilled cider or to add ice cubes to the glass, well – I dun’t knaw.

Recently, (Aug. 2006) the National Association of Cider Makers has jointly funded research into the health benefits of drinking cider. It is thought that English cider apples contain phenolics which could be linked to protection against heart disease, strokes and cancer. One Devon cider producer even cites the example of a local woman who suffers from arthritis. She began drinking a pint of cider a day and found that the symptoms were greatly reduced. Her family became concerned that she was turning into a ‘cider head’ and insisted her daily intake was reduced to half a pint following which the pain returned?

As previously mentioned many of the apple crushers were made from local granite and to this day it is still possible to find part finished or abandoned cider making artefacts on the open moor. Jenkinson, 2001, p19 lists many of the more noted examples:

| Artefact | Location | OS Grid Ref. |

| Apple Crusher Base | Tors End | SX 6148 9258 |

| Apple Crusher Base | Belstone Common | SX 6140 9246 |

| Crushing Pan (1st half) | Sourton Tors | SX 5460 8950 |

| Crushing Pan (2nd half) | Coombe Brook | SX 6223 6250 |

| Runner and Base Stone | Pupers Hill | SX 6740 6720 |

| Crushing Stone | Doe Tor Farm | SX 5340 8495 |

| Runner | Bench Tor | SX 6890 7209 |

| Runner | Merrivale | SX 5582 7492 |

| Millstone | Beacon Rocks | SX 6685 5912 |

| Millstone | Rippon Tor | SX 7460 7550 |

It is thought that the reason these artefacts are still in-situ was that it was cheaper and easier to fashion such heavy items on the moor as opposed to hiring wagons to bring large unfashioned blocks to a workshop. Thus if any were broken and damaged during the manufacture they were simply left where they broke.

Here is the traditional for a Dartmoor Cider Cake recipe.

Pre-heat oven to 180ºC or 350ºF gas mark 4

125g/ 4oz butter or margarine

125g/ 4oz sugar

2 beaten eggs

225g/ 8oz self raising flour sifted

1tsp. Bicarbonate of soda

½ tsp. grated nutmeg or powdered cinnamon

200ml/ 7floz cider

1 tbs Cider Brandy

Caster sugar for sprinkling

1) cream together the butter and sugar until fluffy and bet in the eggs

2) fold in half of the four, bicarb and the nutmeg or cinnamon

3) pour the cider into the mixture and mix well

4) stir in the remaining flour

5) pour the mixture into a greased shallow tin, about 5 x 8 inches, 20 x13 cm and bake in the pre-heated oven for 35-40 minutes

6) cut into squares when cool and sprinkle with caster sugar

If you would really like to give it a twist grate 120g/ 4oz of Cheddar cheese and sprinkle it into the centre of the cake before baking, giving you the classic combination of apple and cheese.

Finberg, H. P. R. 1969 Tavistock Abbey, David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

Greeves, T. A. 2005 Dartmoor Cider Orchards, Dartmoor Magazine, No.80, Quay Pub. Brixham.

Jenkinson, T. 2001 Cider Making in Devon, Dartmoor Magazine, No.65, Quay Pub, Brixham.

Marshall, W. 1970 Marshall’s Rural Economy of the West of England, David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

Torr, C. 1970 Small Talk at Wreyland, Adams & Dart, Bath.

Worth, R. H. 1988 Worth’s Dartmoor, David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

Vancouver, C. 1969 Agriculture of the County of Devon, David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor