Imagine walking the moor on a hot, balmy day, salty beads of sweat start to trickle into your eyes making them sting. Overhead a buzzard lazily floats on the warm therms, slowly spiralling up into the sky with a screel of delight. You decide to have a rest on a large sofa sized granite boulder. Taking out your water bottle you slowly sip the cool water taken from a gurgling brook you passed on the high moor. You can faintly taste the peaty tang. Feeling restored you start to drink in the surrounding landscape. As your eyes roam over the many features you notice a small stone circle below. Suddenly the realisation that the stones are slowly swaying sends a slight shiver down your back. You double check your observation but they are still rhythmically moving. Logic jumps to your rescue, it is hot, it is midday and so it is a heat haze making them appear to shimmy. You look again, nothing else in their vicinity is moving, it is just the stones. The buzzard is now slowly circling above the circle, he knows the truth. You become aware of a gust of wind blowing down from the tors behind you, it sweeps across the moor toward the circle and then it is gone. A single blast of wind like the final breath of a dying identity. You look at the circle again, the frown on your forehead squeezing out more droplets of sweat, goose bumps creep up your arm. Now the stones are static, a stonechat alights onto the largest slab and starts its tuneless titch, titch song. You take a final gulp of water and move off down the hill, desperately trying to ignore the past few minutes. A final glance over your shoulder shows you a circle with a secret…

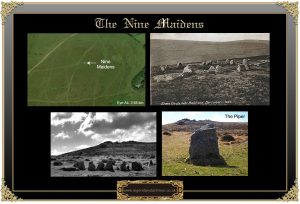

Confusingly, this Nine Maidens is also known as the Seventeen Brothers although marked on the Ordnance Survey map as the Nine Stones. But either way here is another example of what can happen to people who break the Sabbath. This circle is or was a group of maidens who danced on a Sunday and were immediately turned to stone. Not far from the circle is a small broken stone who is supposed to have been the piper who played for the maidens. For their punishment they were compelled to dance every day at noon for the rest of eternity and it is said that to this day they can be seen rhythmically moving at midday. It is also suggested that the sound of the Belstone church bells will also bring them to life. Another version is that the assembled crowd were in fact seventeen brothers who were turned to stone for dancing which seeing as this is the number of stones visible today would appear the more favourable of the options. Legend also has it that when counting the stones the same total can never be reached probably because the dancers won’t stand still long enough.

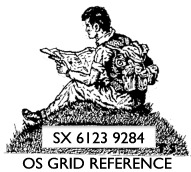

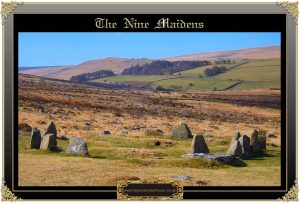

The Nine Maidens are in fact a cairn circle or kerbed cairn which stands in an area of clitter (a scattered rock field below a tor where due to erosion the rocks have emanated), ironically this may have saved the site from destruction at the hands of the stone masons. Today the circle comprises of sixteen stones, one has been uprooted outside the circle, one lies buried and two are almost leaning flat with just the tops visible. Most of the stones range in height from 0.5m to 0.8m, however a fallen slab does measure 1.75m and must have stood higher than the rest. These stones would have encompassed a central burial cist or as they are known on Dartmoor kistvaen. The interior has been dug into as is evident from the spoil heap lying to the south west of the circle. It is estimated that originally the mound would have covered the burial kistvaen and stood as high as the stones, Butler, 1991, pp.208-9. Hemery, 1983 p.857, suggests that the internal diameter of the circle is 7.01m. He also notes that when in 1923, Richard Hansford Worth surveyed the circle there were sixteen stones standing which clearly was not the case when he photographed the circle.

In her book The Witchcraft and Folklore of Dartmoor, Ruth St Leger Gordon, p.69, Gordon notes that nationally there are many examples of stone circles associated with the dancing legend that are known as the Nine Maidens, regardless of the actual number of stones in the circle. She suggests that latter day witches worshipped the moon at these sites. They believed that the moon went through three phases, crescent, full and waning. Each phase was represented by a different lunar goddess. These three phases were then further split into a further three phases each with its own goddess. This gave a total of nine moon goddesses, each concerned with different occasions and circumstances which may account for the frequency of the number nine in the place names of such sites, along with the similarity of the nine Muses or the nine Valkyries.

Going back further in time, it has been suggested that the name Belstone refers to the god Baal and derives from Baal’s Ton (settlement). This Victorian interpretation stems from the idea that a group of Phoenician traders found themselves on the range of tors and here they worshipped the God Baal. They then built a settlement known as ‘Baal’s ton’. Later records tend to dispel this idea for more plausible explanations. However, this in not the only reference to the Phoenicians being on Dartmoor.

Further adding to the confusion about the actual number of stones, it is known that in 1985 a horror film called ‘The Circle of Doom’ was shot at the circle. In an attempt to embellish the setting the film crew erected an additional stone in the circle. Remembering that legend has it that anyone interfering with the stone circle will be cursed, strangely enough the sole copy of this finished film was lost in the post, Walpole, 2002, p.16.

Another noteworthy fact is that the famous St. Michael’s ley-line actually passes through the circle, narrowing from a width of 7m to a point as it does so.

Again the legends of the Nine Maidens seem to be a warning to people not to break the Sabbath or to interfere with sacred sites. Clearly this has not worked here because as with many of the Dartmoor burial cairns they have been opened and robbed of anything of value. Clearly we now know that although the contents are archaeologically valuable from a monetary aspect they would have been worthless and certainly not classed as treasure. However stories of ancient kings being buried with their treasure must have had an appeal to a poor moor dweller who was prepared to risk the various curses involved with these sacred sites.

Butler, J. 1991. Dartmoor Atlas of Antiquities – Vol. 2. Exeter: Devon Books.

Hemery, E. 1983. High Dartmoor. London: Hale.

St. Leger-Gordon, R. 1972. The Witchcraft and Folklore of Dartmoor. Wakefield: E P Publishing.

Walpole, C. & M. 2002. The Book of Belstone. Belstone Community Project.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

2 comments

Pingback: Nine Maidens dancing on Dartmoor | Dartmoor Hiking

Pingback: ;) | Provocation of Inspiration