The arrival of the railway to Lustleigh heralded a new dawn for the little village and one that would eventually put the place well and truly of the tourist map. People began making their ‘pilgrimage to the picturesque ‘Lustleigh Cleave’ to enjoy its beauty and tranquillity. Initially it was quite a culture shock to both the visitors and the locals but as time went by both began to adapt in a timely fashion. Here is an account from 1868 which demonstrates both the splendour of the Cleave and the sparse amenities available for the visitors of the time.

“The village of Lustleigh is situated between Bovey Tracy and Moretonhampstead, being distant about four miles from the latter place. Till lately it was little known, but since the opening of the Moretonhampstead Railway thousands have poured forth from the Lustleigh Station to explore the Cleeve and its superb surroundings, nestling amid hills where the air is always pure and bracing, and where beauty is sown broadcast on every hand, Lustleigh, which now contains only a few straggling houses and cottages, is sure to become a favourite resort for tourists and health seekers. Indeed, as it is, demand for lodgings is far greater than the supply. Dwellers in towns, too, who may come to rusticate here, will find few lodgings in which they will not have to “rough it” in some respects, much as if they were camping in a prairie or a primeval forest. Sanitary arrangements, for example, in many cottages, are conspicuous by their absence…

Those, therefore, who wish to see the country, and who will afford the time and the money, will do well to hire a conveyance from Newton. “Don’t forget the hamper.” So say we to those journeying through the moor country; however interesting may be the society or circumstances. “Don’t forget the hamper.” Hunger may be a very vulgar thing, but the higher part of our nature is apt to get out of tune even in an earthly paradise if the “hamper” be forgotten. Those who have secured the services of a competent driver may be put down by him near the Cleeve. But if parties concerned have moderate walking powers, it will be best to leave the vehicle in Lustleigh, and proceed the rest of the way on foot. If they wish to picnic amongst the rocks, some sturdy villager may easily be found to convey the “hamper” thither.

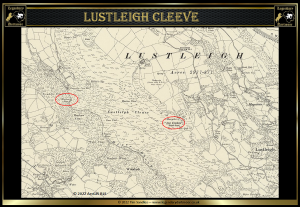

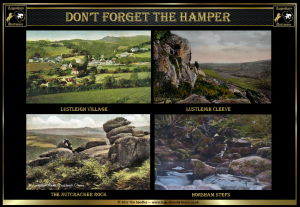

At the end of Chapel Lane there is a copse of oak trees, through which the road to the Cleeve winds. A wild and romantic aspect is given to this copse by the boulders with which it is strewn, many of them of immense size, and overgrown with moss, ivy, and ferns. As we gradually ascend the copse, new and charming peeps of woodland and hill scenery present themselves at every turn. The road beyond this copse is continued by another nutty lane passing through some farm buildings. At the end of this lane the road divides to the right and left, and as there is no fingerpost, the tourist should remember to turn to the right, or he may get far out of his way, and not readily get into it again, for in this sparsely peopled country he may go miles without meeting anyone to direct him. Taking then the road on the right, the entrance to the Cleeve is soon visible on the left-hand side. This is a narrow path with boulders. We now emerge upon a hillside, and reach the spot generally visited first by tourists, where the most striking features of the landscape can be seen at a glance. The hillside is just referred to rises very abruptly, and is covered more or less thickly with boulders from the base to summit. The best way to climb this rugged steep is not to attack it in front, but to follow the path by the wall on the left-hand side, from which several paths diverge, by any of which the ascent is comparatively easy. When fairly on the top of the hill we are in the midst of a sort of natural fort, formed of vast masses of stones piled up in picturesque confusion. One of these boulders is a Logan or rocking stone, and is known locally as Nutcrackers rock. So delicately balanced is it upon a similar stone beneath that a child may use it to crack his nuts. One can hardly look on these gigantic rocks without asking, whence came they? They look as if contending armies of giants have made the Cleeve their battle-field and had fought each other with mighty fragments torn from the living rock.

From the summit of the hill the ground slopes down at first, almost perpendicularly, and then more gently, forming a wide ravine, which is, in fact, the Cleeve – i.e., cleft, – and extends for several miles. The name doubtless indicates its origin. Countless ages ago the ground was cleft asunder by stupendous subterranean forces. Throughout the bottom of the Cleeve runs a pellucid stream, which is called the “Bovey” river. Fringed with shrubs, its waters are scarcely visible from the top of the Cleeve, though its winding course may be clearly traced. The opposite banks of the river rise to a considerable height, and being clothed with woods and swelling out in exquisitely rounded outlines form a picture of wonderous gracefulness. Far above the banks of the river, the high land, being partly meadow, partly moor, and partly corn fields, inter dispersed with clumps of trees, and being moulded by the Divine Artist in irregular yet symmetrical undulations, forms a grand crown to the wood and river scenery below.

By following the path along the crest of the Cleeve, which extends to a great distance, many magnificent views may be obtained, but being anxious to see the famous Horsham Steps, we descended from the cluster of rocks so often mentioned and took a path to the right on the hillside which gradually leads down through furze and brambles and ferns down into the valley. After walking about two miles, we reach the banks of the river and soon are standing on Horsham Steps. Once seen, this natural bridge will not easily be forgotten. It is made up of masses of rock, weighing some of them not more than a ton, and others not less than a thousand tons. They completely cover the river for a space of about 30 feet in width and about 180 in length. Through their interstices you can here and there see the river rushing along below, and where you cannot see it you must be deaf indeed not to hear the noise of the waters fretting and chafing and roaring as they seek a smother channel. Manifestly it was the immense size of the rocks that preserved in its present bed the course of the river. Had they been smaller they must have choked up the channel and diverted the stream, but falling as it were in each other’s way, they thus were shaped into a rude arch, beneath which the waters have ample space to flow.

As Horsham Steps cross a secluded bend of the river, and you are completely surrounded by trees, they form a “sweet pretty” nook where the visitor may sentimentalise, philosophise, or yield to greater influences. One secret of the attractiveness of this scene has been well described by a recent writer – “There is a kind of lingering stream which makes it just the companion of country solitude which a poet loves and teaches us all to look for. The tide of life along the streets runs dry at night, but the brook or the river runs on day and night with volume only varying as the season change. We go to it year after year for rest and holiday, and there it is rushing over the same stones, singing the same lullaby to our cares, and leading up with the same look of welcome which our own holiday feeling reflected on it at first.”

Whilst resting on this unique bridge one could not help thinking of the generalisation that had come and gone since those hoary stones were hurled into the riverbed, and of the history and the destiny of the thousands who had used them as “steps” to reach the hamlet of Manaton above. Where are they now? Had they grace to use the steps which God has placed across the stream of life to reach yet higher heights? Ages hence, when the river is still rolling on, where shall we be?

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor