“The Moors, at this season of the year, offer peculiar attractions to the tourist, and it is solely with the desire that I may show those who do not at present know of their capabilities as healthful and interesting places that I venture to put a few of my observations on paper. It is a matter for regret that I am unable to recommend a trip which I recently made over Dartmoor to any but fairly athletic, stout-hearted and lithesome men. High roads are never overwhelmingly interesting, and bye-ways must be traversed by those who are lithe and apt. Occasionally, on the Moors and their neighbourhoods, one must be his own pioneer, and a path must be made where none before existed. And, while hydropathy is a valuable feature of therapeutics, those not blessed with good constitution might experience some discomfort from ambling up and down a river bank ‘in puris naturalibus‘ (naked) until such time as the sun might dry his clothing which, with its owner inside, had recently been immersed in the stream (besides, it requires considerable exertion to wring out a pair of unwhisperables so that they may be re-assumed with some measure of comfort); and, again gastronomers might protest, after partaking of bacon and eggs three times a day, against being presented by way of variety, with luscious, but unduly (considering what has gone before it) oleaginous harm. But these are matters which go to make up some of the events of a ramble, and those who are naturally unfitted to compete with them may not venture upon this trip.

The route which I and my companion took is given below in the shape of extracts from a diary which I kept. There are, of course, a great many things to be seen which cannot be detailed. But the principal features of the walk lend themselves to portrayal. Here a word may be said of the outfit which is desirable. This merely consists of the clothes you stand upright in, a small supply of linens, and last, but paramount in importance, two pairs of light boots. With the exception of about ten miles, the whole of my walking was done in a pair of lawn-tennis shoes. It is well that a person should take two such pairs, using them on alternate days, and changing those worn for for the spare ones (serving the purpose of slippers.)

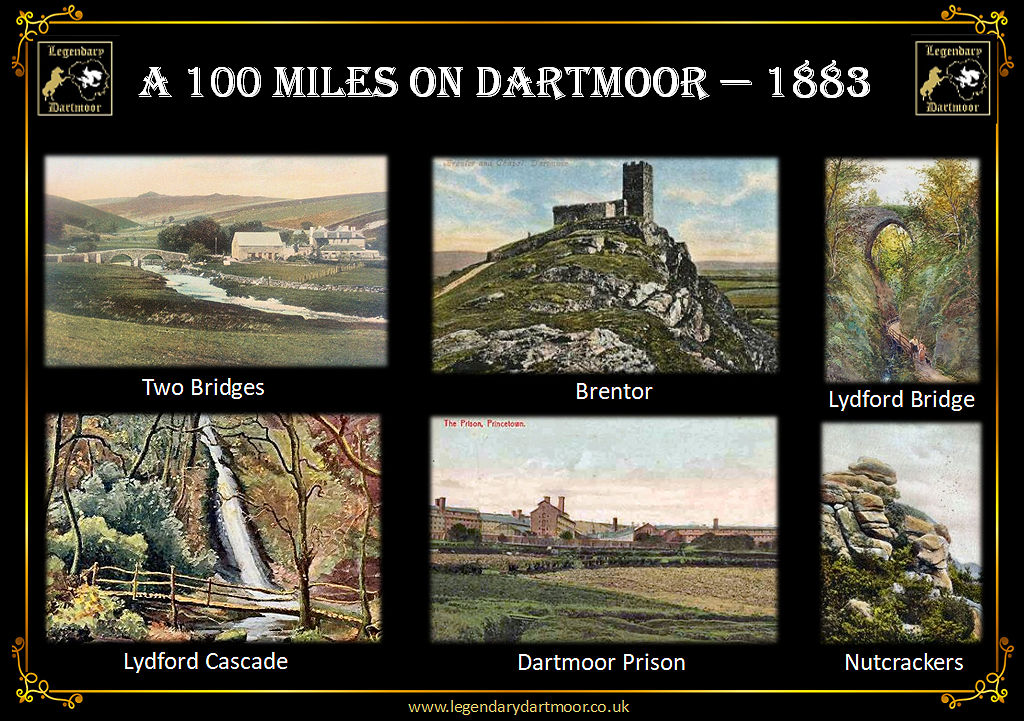

The Moor is fairly reached at Poundsgate, and it is convenient that a halt should be made at Twobridges or Princetown. The walk from Ashburton to Twobridges afford an opportunity for the enjoyment of some magnificent moor views. One is altogether fenced in by rugged tors, with sparsely verdured approaches, interrupted by boulders set promiscuously about, as though tossed hither and thither by giants in a potent fury. The eye up to the horizon, rests only upon the outline of the distant hills – hills which one will skirt in his later peregrinations – flecked occasionally with a wind-blown bush, and always dotted with huge stones, natural, they would seem, and cromlechs and tolmens. The Moor paths are of excellent kind; hard, smooth, and scarcely muddy even after rain. Rain runs off the granite flooring as from paving stones. Should Twobridges be reached fairly early there is time for a walk to Princetown, which is worth seeing on account of its pre-eminence as the bleakest and most wretched place (in winter) that can be conceived. Every wind that blows takes Princetown in its course; when the sun shines on the surrounding country, Princetown rains, when the air is pure and bright and wholesome elsewhere, Princetown in enveloped in a fog. Princetown exists because Dartmoor Prison exists, and the whole combination is dismal, suicidal, gruesome. You see from afar stone mounds, with semaphore posts, devised to signal the escape of a convict, others occupied by warders having oversight of gangs of convict labourers in the fields, and by the aid of a field-glass, such gangs can be descried, hemmed in by officials in positions well-calculated to afford them a crack shot at runaways, engaged in various occupations. The roads about the penal settlement are bordered with stone walls, these are latter day work-grand, grey facades of stone upreared by convict hands, with marvellous mechanical precision. Great quantities of land have been reclaimed by convict labour, and there are many acres of arable land, smiling under cultivation, which were barren, stony fields. Twelve hundred convicts get through a deal of work, under compulsion. There are two plots of ground by the prison side, the burial places of the French and American war prisoners, who died there between the years 11809 and 1814, marked by simple obelisks, bearing as epitaph, ‘Dolce et decorum est pro patria mort‘ (It is sweet and fitting to die for the homeland).

On the road to Tavistock from Twobridges, on the left, a little before the Dartmoor Inn is reached, are some Celtic and Druidical remains, in a truly wild spot, a fitting place to do service to Ball and Ashtaroth. And cosmogonists not recognising the mosaic history may speculate upon the forces which, hither and thither, disrupted the landscape, and the upheavals which belched out fantastic shapes of ponderous stone. In Tavistock the name of Bedford is all pervading. The Duke of that ilk hath done great things for Tavistock, and his paraph is upon its streets and its institutions. Any bird’s-eye view of Tavistock should be labelled, “Erected by the Duke of Bedford.” When we arrived, later on in the journey, at huge Yes Tor we found there had been one before us who had passed through Tavistock. His mind had been ‘kinked’ by the ever obtruding legend in that town, and in bold characters, he had written on a discarded paper front, affixed to the award of the high tor by a pin, the ubiquitous inscription “Erected by the Duke of Bedford”.

Between Tavistock and Lydford is Brent Tor, adjudged to be an extinct volcano. Some individual of mental obliquity conceived this to be an excellent site for a church; accordingly, there is an edifice on the extreme elevation of the tor – a solidly built, square towered church – with approaches, or rather lack of approaches, which in all probability, make church-going at Brent Tor an event of rare occurrence.

“They have a castle on a hill. I took it for an old windmill, The vanes blown down by weather.” – These lines – I think I quote the Tavistock poet correctly – apply to Lydford, which I have the hardihood to asset, is the prettiest village in Devonshire. I fear that in early times the place had not a highly moral tone, for the poet remarks, “I’ve oft heard tell of Lydford Law, How in the morn they hand and draw, And sit in judgement after.” Either it is Magna Carta had no respecters in Lydford, which, en passant, a barbaric railway company persists on spelling Lidford, or, that Judge Jefferys having held a sanguinary assize there, the contumely adhered to the place for after-time. Look over Lydford Bridge, say about noon, om a summer’s day. See the straight sunrays vainly endeavouring, in an air which is hot and still, to pierce down into those dreadful depths, where one could think the world is dead and buried, all o’er-shaded with painted leaves. Higher up the river babbles over grey stones, but here it is sullen and anon fretful, because the sun can never reach it, and deep and icy. Great trees which have their roots in the sheer sides of the gorge intertwine their foliage, arch after arch, above the stream, and, peering down from the bridge one may only see the dull, glowering green of the leaves, giant ferns with varied fronds, and, below all, surging along, and tumbling into black holes, tunneled by the stream itself, the water, surmounted by faint spray, and bearing to those above the gruesome sound of running waters. The locals tell of direful happenings here – how a horseman rode into Lydford from Tavistock one night, when the bridge was gone, how it transpired that in his ignorance he had rode straight at the fearsome chasm, and how he felt his horse take a terrific leap – a leap which held him from a dreadful death. There is a private path into the gorge, information about which is given at the inn. It is a wonderful descent down to the river-side. You reach it by means of a sinuous path, bordered with luxuriant foliage of that dark green born of a shaded growth, British orchids, rarely coloured, a late primrose, long twisted vines, a damp undergrowth of mass and fern; and so on to the diaphanous water, where innumerable trout flash from under stones, and triumphantly stem the torrent, secure from the fisherman’s fly, and seemingly jubilant in the circumstance. The sight on all sides, and above, is gorgeous; I could not do it justice, but I give the practical testimony that in all my wanderings I never beheld such a scene of such glory, such a “soothing, moving, satisfying scene. From out of the hurly burly to this place is as charming a contrast as can be imagined. You may walk along the gorge to Lydford Cascade – a silvery downfall of water, beautiful to look upon.

There is a beautiful stretch of country between Lydford and Okehampton, but of the town I am unable to speak, because after a glance at the encampment of the Royal Horse Artillery, and a view of Yes Tor, we pushed on to Sticklepath, the neighbourhood of which place is rich in its scenery, and of no insignificant interest to the antiquary. Awaiting the preparation of our evening meal we strolled up the side of a streamlet and came upon some rugged and picturesque pieces of country, on the slopes of which, “The rabbit wild and grey, that flitted thro’, The shrubbery clumps, and frisked, and sat, and vanished. But leisurely and bold, as if he knew, His enemy was banished.” It is a delightful walk from Sticklepath to Chagford. One’s route is through real Devonshire lanes – lanes which are reverenced by those who know them as national institutions. And from Chagford – this I whisper as a “dead secret” – one should go up the fishing path, bristling as it is with the terrifying intimations “Trespassers with be prosecuted,” “Private,” to Fingle bridge, warily stepping on the mossy stones jutting over the waters of the Teign, and using his wood and water craft, like the Indian kinsman, but in a humbler way, between tall cliffs massed with the pollard oak, and conical hills dressed in low shrubs and broom. And then the route leaves one in the healthful town of Moretonhampstead, where a pleasant inn ministers its grateful comforts.

Lustleigh Cleave is withing easy distance of Moretonhampstead, and it is a fitting place to conclude a week’s ramble on the Moors. The fair scene from its rocky heights is very good for the yes, but the climb tires one, and he is pleased to lie at full length under the “Nutcrackers” until such time as he needs must bestir himself to wend his way to the station, to be borne back to his daily labour, all brown and fresh and strong from his walk on Dartmoor.

I have omitted mention in the foregoing of one place, because it may be visited only as a privilege. Those who can obtain a permit should make a point of visiting Buckfast Abby, the settlement of a body of French Benedictine monks. Within the present enclosures, by the aid of so kindly a guide as the Rev. Dom. Hamilton, there can be inspected the ruins of a Cistercian religious house which flourished from the latter part of Saxon years to 345 years ago, when sharing the fate of other houses of the religious, it was supressed. The present occupants have bought the place; they will, so far as possible, restore it, labouring each with his own hands at the craft which must contribute to the restoration – no uncommon matter, nor any hardship, for the fathers perform for themselves all offices, down to the making of their sabots, needful in a primitive community. Father Hamilton spoke with unconcern of the prospect, during the coming winter, of the monks reciting their offices at one or two o’clock in the morning in the open air.

I fear that by expatiating further than I have done upon the beauties which spread themselves out before the Moor traveller I might become tedious. Holne Chase, in the valley of the Dart, has not received particular attention, and only a portion of the wild Moorland scenery has been noticed. But, probably, enough appears to demonstrate the suggestion that those who love the country, and revel in a variety of scenery, and desire to breathe the while fresh, invigorating air, can spend a holiday nowhere better than Dartmoor. Therefore I pass on to the extracts from my notes, pausing to say that I will supply anyone who may write to me at the Torquay Times office with particulars showing the best hotels to stay at, the cost of the outing, and the mileage from place to place (The entire distance walked by us during the week measured close upon 100 miles).

The route, then, is as follows:- From Torquay to Dartmouth; thence to Totnes by steamboat; Totnes to Ashburton* (leave the main road at Staverton Bridge, and walk along the railway to the riverside), by way of Buckfastleigh; from Ashburton, go through Holne Chase and Poundsgate, to Twobridges*; thence to Tavistock, crossing Merrivale Bridge, passing Brent Tor to Lydford*; Lydford to Okehampton, and Sticklepath*; thence to Chagford, and from Chagford to Finglebridge by the fishing path, to Moretonhampstead*; Moretonhampstead to Lustleigh Cleave, and home. – The asterisk* denotes the halting places.” – The Torquay Times, June 15th, 1883.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor