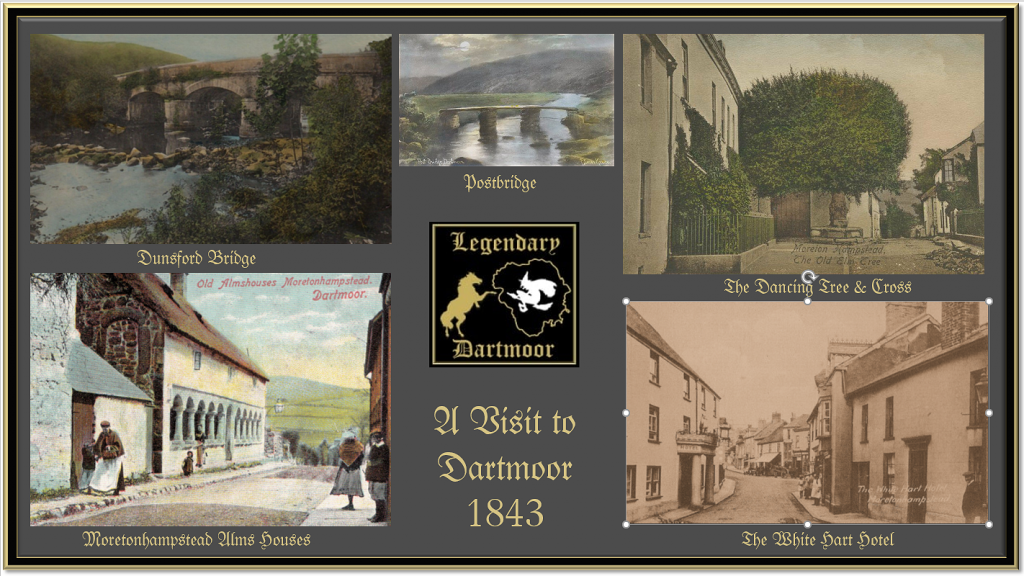

“A Visit to Dartmoor 1843 – On the afternoon of last Friday we left the city (Exeter), and not knowing of any regular conveyance, and being rather partial to pedestrian exercise, determined to accomplish the journey on foot. It may be unnecessary to go over the often-related tale of Devonshire beauties, where the hand of man has marked the progress of civilisation by the improvement in the fertility of the soil; suffice it, that having noted the lovely tracts of cornfields, pasturage and woods, enlivened by the constant succession of hill and dale, which at numerous intervals opened themselves to our view, we arrived at Dunsford Bridge, a really romantic scene, in which nature having done so much and having done it so exquisitely, is allowed to retain the mastery. The bold stream of the Teign, winding along the base of woody hills, whose precipitous sides appear almost to touch the empyreum, presented its apparent basin of waters enlivened by the numerous ripples caused by the fat trout as they rose for the evening flies. But our course was onward, and lingering but a few minutes, as loath to leave the lovely spot, we pursued our uphill way.

About five more miles, (during which we were lighted by the best half of the harvest moon), and we entered the secluded town of Moretonhampstead. Tourists describe is as peculiar in its exclusiveness and near approach to the primitive simplicity of our forefathers, and we were by no means disappointed in our search after the picturesque. Almost the first house on the righthand on entering, was striking for its peculiarity. Imagine, gentle reader, a long low house glittering with whitewash, the upper storey supported by a row of pillars and arches, which gave the lower department or ground floor the appearance of a colonnade, from which half-opened doors led to several apartments. (The Alms Houses). It was altogether so foreign from anything we had witnessed in England before, that we congratulated ourselves on the discovery of such a picturesque locality. A few yards further, and the well-clipped crown of a gigantic tree, whose base was protected by a granite cornice or surbase or something similar, surmounted by a sharply cut granite cross, stretched its long arms across the public path. We afterwards learned that some years since, parties of five or six we accommodated in the time-honoured crown; but that symptoms of decay becoming more manifest, it was thought advisable to discontinue the practice, in the hope of preserving a natural memento of bye gone days, whose origin was involved in the obscurity of ages (See The Dancing Tree).

As it was extremely necessary that we should experience the genial influence of nature’s soft-restorer, we leisurely sauntered the high-street, for the purpose of reconnoitering, and at last selected the hostelry of the active widow, Mary Gray, known as the White Horse. I must do her justice to acknowledge that the comforts she dispensed were more than adequate to our requirements, and her bill a pattern to innkeepers, neat, succinct, and very moderate. In the morning, after performing our ablutions, and as prudence dictated doing justice to the hospitality of our hostess, we departed with spirits light, hopes high, and limbs elastic, to explore the wonders of the Moor. A walk of four miles, and we entered on the moor, bidding adieu to civilisation to welcome the vast fields of the wild and the wonderful, which on all sides were presented to our view in seemingly unlimited succession. It has by many been thought that there is nothing interesting or worthy of admiration in so sterile a district, and that the view of so much barrenness would rather tend to chill than to cheer the spirits. It is true, that there is not the rich woody luxuriance of the vales of Devon, nor the grassy meadows, nor the exuberant hedgerows studded with an infinite variety of wild flowers of gaudy hues, nor the illimitable succession of corn, stubble, pasture and fallows, which in the cultivated districts filled up the view which presented itself wherever an eminence gave us facilities for overlooking it; but there was the majesty of space, the tors whose heads touched heaven, their summits crowned with myriads of blocks of granite, thousands of tons of massive stone, which seemed to bid defiance to the ravages of winter and the researches of philosophers to discover whence they came. A short distance from the road might be seen gigantic circles formed of irregularly shaped pieces of stone, apparently the remains of temples once consecrated to the mysteries of the ancient druids (in fact these were prehistoric hut circles, nothing to do with the Druids); on the left is the remains of a tin mine, which we leave until our return, and then passed in haste. A little further on is the first sign of human habitation, a stone cot surrounded by a low wall and a peat stack; a board suspended nearest the road-side proclaims to the way-worn traveller that Jonas Coaker is a licensed victualler, (this would have been the New Inn which originally stood opposite what is now the Warren House Inn, just after this account was written in 1845 the Warren House Inn was built and replaced the New Inn). His wife is the mother of four really fine and truly clean children, whom she assured us she was bringing up on the moor, and they certainly did credit to their pasture. In the hollows, between four and five miles inwards, are several cultivated fields and one or two stone houses, and a bridge over a stream, in whose pellucid waters we could observe a large trout enjoying his olium cum dignitate. Lower down the stream was another bridge worthy of the days of King John and Gurth of Wambs, upright pieces of the interminable granite, crossed by long large slabs of the same material, (Postbridge) and worthy of the pencil of Landseer. From this point onwards the road was bounded by stonewalls miles in length, – indeed we could not discover their termination; we therefore crossed, and having picked our way through a living bog, ascended one of the majestic tors for which this place is celebrated. In our way to the base of this minor mountain, we had to cross one of the wildest and most romantic streams it was ever our good fortune to witness a liquid clear as crystal, making its precipitous descent through a mass of rocks tumbled in caste confusion, here insinuating itself between the huge blocks, there ruching in furious rapidity, again pent up in clear pools, and then overbearing every obstacle, forming miniature representations of Niagara.

On the summit of the tor we partook of the slight refection we had provided, our table being estimated to weigh above fifty tons, at an elevation of two thousand feet; and having quenched our thirsts at the crystal stream, and refreshed our rather wearied limbs by an elevated siesta, we prepare3d for our return. The view from the summit where we stood comprised of numerous tors or high granite-crowned points, between them lay thousands of acres of wild moorland strewed irregularly with enormous masses of stone, as though hurled by a mighty hand or scattered by the fury of a tempest from unknown quarries; while at intervals the regular lines of blocks bore the appearance of having once marked a track across the waste. Here and there were distinctly observed circles of stones which, if as we supposed, were the temples in which the ceremonies of the Druids were performed, displayed the skill which had been exercised in the selection of spots so suited to the maintainace of superstitious awe.

Time will however wait for no man; and we were constrained to leave the enchanting elevation on which we stood, to return to the haunts of man. The appearance of the lower grounds as viewed from the heights was rather singular, the lower clouds which floated over them, seemed to hang like a fog, or the smoke slowly clearing away from a battlefield. A brisk walk of about ten miles brought us to out inn, where having temperately refreshed with the aid of Mrs Gray’s souchong, we completed our pedestrian excursion by a moonlight walk of twelve miles, to the faithful city of Exeter, at which we arrived about eleven o’ clock. My companion was but slightly fatigued, and the only inconvenience I suffered was from a broken blister, which was speedily cured by two or three applications of Emmett’s family salve. We were unanimous in the great delight and gratification which we had experienced, form a walk so accessible to all in Exeter who possess the requisite health and strength. – VIATOR.” – The Exeter & Plymouth Gazette, September 9th, 1843.

It is worth remembering that at this time many people, including some antiquarians considered that the prehistoric hut circles, stone circles, rock basins of Dartmoor were relics of Druidical practices., hence the references to Druids. Nevertheless this was on hell of an excursion and no wonder ‘Viator’ had a blister!

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

I think the pub mentioned may be what is now known as just ‘The Horse’ previously The White Horse not The White Hart as pictured. Nit picking I know! Love these accounts, keep up the good work! Thank-you