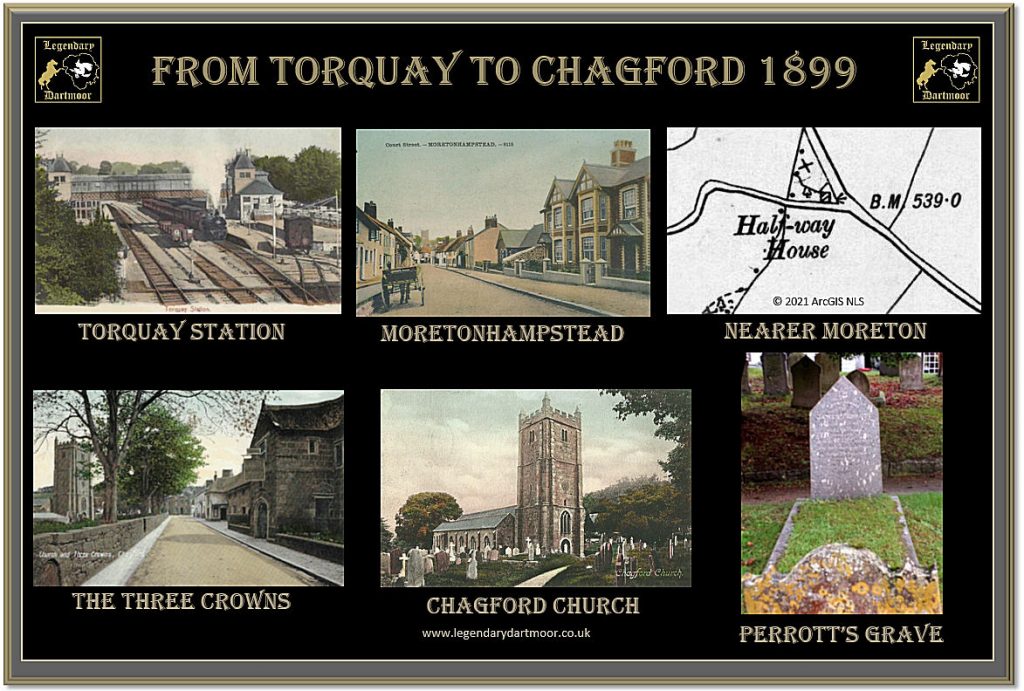

Today if you wanted to travel from Torquay to Chagford it would take 59 minutes to travel the 26.8 miles by motor vehicle. Imagine for the same journey in 1899 you had to get a train at Torquay Station travelling to Newton Abbot then passing through Bovey Tracy and on to Moretonhampstead Station. Having reached there board a coach and horses to the final destination of Chagford. What a superb variety of Devonshire landscape you would slowly trundle through with time to watch and stare and observe the dramatic change from the salty coastal lands to the fresh and bracing air of the Moors. What follows is the experience of such a traveller back then…

“One of Torquay’s great advantages is its nearness to the Moors. You can run from the soft seductiveness of Torquay right into the bracing atmosphere of the Moors in a very short while. It is a matter of no great exertion. Stroll down to Torquay Station, get into a railway carriage, read the morning paper, smoke a pipe, grumble at Newton Abbot Station and its delays with the zest of and Englishman, and there you are. Not perhaps at the best point of vantage on Dartmoor, but still in those broad, grand harvest fields of the bees. A summer morning with the sheen of the morning sun lying broad over the bay, waking to warmness the white faces of houses, they grey faces of houses, the ribbon roads, the quaint pastures of flower worlds, the clean well-groomed station. A summer morning that sets my fellow travellers looking up at the temperatures of town and grunting over their pipes in satisfaction of at the comparative coolness of their own town, and prophesying the noontide heat that will be good for the harvest but trying for mankind. We are off to the Moors. We are jubilant, very jubilant. We are rather inclined to crow over a County Councillor doing a weary journey to Exeter, with the prospect of a long droning afternoon at committee work. We paint the prospect of breeze blown, bee hunted breadths of heather, with anticipatory glow of colours, we sketch the delights of lying beneath the shade of grey granite rocks, smoking pleasant pipes with vast panoramic pictures stretched for one’s lazy pleasure with inward satisfaction. Then the doldrums of Newton Abbot safely passed, we detrain gleeful passengers at Bovey Tracy for the waiting coach, and finally steam into Moretonhampstead with all the fussiness of a local than which there is nothing greater in all the world of expresses.

Here, however is not our destination. In all the heat of the sun poised above us, in direct cognisance of our movements, we clamber up to the top of the Chagford bus. We are in no hurry to start, Devonian socialbleness sends our driver retailing the small goods of local gossip to all and sundry, the while collecting boxes and bags that are to be piled laboriously on the broad top of the vehicle. The horses faces contorted with vain attempts at disconcerting the persistent flies, stand patiently enough although the snorts of one of our fussy little locomotive upsets the equanimity of one so far as to set an aged porter ambling slowly to soothe him with somnolent sibilants, whispered comfortingly in his active ear. Then there is a gathering up of reigns, a vast parade of importance, and we lurch out and roll up the hill on the long stretch to the town with an importance never granted to anything vehicular beneath the rank of a Devonshire bus of Lord Mayor’s coach. The great topic of conversation, all engrossing in these rural towns, is the subject of dinner. The real Devonian lives to eat and drink. The making of Junket is more to him than the building of an Empire, the successful engineering of clotted cream compels his admiration far more than the accomplishments of the Peace Conference. We pick up a police sergeant moving stolidly and slowly in the direction of Chagford. He seems burdened with the consciousness of the farce of visiting Chagford. Crimes are rarely committed in villages – they are left to the towns. He is burly and is getting on in years. Not old, of course, for these fellows reared on the confines of the Moors have have found the secret or perpetual – well if not of youth at least of comfortable dinner appraising middle age. He is diffident at first. We have spread ourselves out on the bus and visibly shrink and squirm, the structure of the bus groans a protest, and we are four in a row, as neatly packed as any pilchards masquerading as a sardines. There is an angular old man alongside me, acting as a buffer to the iron railings outside, and I begin to wonder whether pressure against the iron rail would be worse than against his painfully obvious bones. He is not Devonian I gather from the gatling fire of sentences the peculiarly vivacious driver fires semi circularly around him. We pass the halfway house which the driver explains is much nearer Moreton than Chagford, and sets me wondering whether some remote strain of Irish ancestry has suddenly emerged from the oblivion of years. The police sergeant who in his rounds passes the upper watershed of Torquay watershed is much concerned with the probable dimunation of the game. “The partridges go wur their feed be, an’ seemin’ly in a year or two there wont’s be a feather there.” This is all very alarming, but I comfort myself that we have not spent the huge total of thousands for the sake of preserving game. In fact I reason that game would not be worth a candle.

Chagford, white faced of houses and ruddy countenance of man, serves us in the matter of lunch, eaten in the room of The Three Crowns, looking out on the churchyard and the toil of one making a grave with passive submission to the sweltering sun. The church has a kindly, grey, watching face, as though it had chastened but not unpleasant thoughts of those sleeping amid the grass at its feet. Through our meal, ending as most Devonshire meals end with cream and fruit, the heavy monotonous stroke of the pick comes in at the window with a laborious regularity of slowness. The meal finished we stroll through the churchyard and see the granite tomb erected to the memory of Perrott and his wife. It is hard to realise Chagford without Perrott. In him we had one of the finest moormen, sterling, rugged, honest as the outcropping granite of his beloved moor, and now the granite marks his resting place, a fitting memorial for one whose life was passed in the companionship of the granite-crested tor and stone-strewn moorland stream.

Out again in the broad sunlight of the staring street, with the slow measured blows of the pick following us. These evidences of death here are not gloomy for the sun shines and the churchyard is decked with flowers, and the sleeping of those in the grassy beds seems to us of little duration. There is the grass which grows luxuriantly, and will be cut down in a little while, and yet again in the Spring will rejoice in a new life. Does it not teach hope for the morrow – the one great lesson that all the perennial flowers teach us year by year. Shrill voices call from the lips of the living children. They play among the head pieces of the graves. The village is full of busy life, the things of life are calling very loudly to the businesses of the short day that must set and be curtained by the night of the churchyard. Our trap is here, we mount, we clang the door, we start at a round trot, clattering through the noisily cobbled streets of the village. Dogs bark and fly out in aggressive attack upon our moving wheels. The air is sun-permeated, hot, luscious. The tors are purpled with distance, and starred here and there with houses. And as we clatter we are pursued by the slow warning strokes of the gravedigger, making the last bed of someone unknown who has played his or her little part in this drama a village life, and has now slipped behind the great curtain that ends our play.

Down the hill we go more sedately for the declivity that set us in a sudden upon the delightful scene of Holy Street Mill is no more gentle falling away but some hill of steepness closured by high walls and banked hedges: up again cresting the opposing hill and jaunting it happily along with the happy drowsy contentment of noon far gone, catching here and there tall fox gloves, hanging purple bells, sweet breathed honeysuckle, coquetting butterflies, honest soberly industrious bees; seeing green meadows with fringes of trees, wheat and oats and barley growing to the harvest swaths of hay, not yet concreted into stacks, hay stacks newly built and giving to the air that nameless scent which is so penetrative and insidious. So we go with a loquacious driver, glad to familiarity to find that I know somewhat of old worthies of “Chaggyford,” telling of the death of this one, the departure of another, the great advancement of a third, and so on with easy garrulity of village life. Then we drop again, see the spread of a village fair at South Zeal, with men ambling round the fields on horses in the curiously toy-like atmosphere of distance, pass disused mines which have vomited out rubble that fall sin treacherously smooth banks to the roads through Sticklepath with its picturesque houses set at the rear of old world gardens and by a devious course, so avoiding the steepness of the way by Skaigh to the little village of Belstone which is to be our home for the next few days.” For this installment follow – HERE.- The Torquay Times, July 28th 1899.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor