Following on from the 1899 Torquay to Chagford excursion this now takes up the next leg of the journey to Belstone. I wonder how many people fortunate enough to live on the Moors still take pleasure in the various unique sunsets, the seasonal changes of the agricultural year and the fresh bracing air which surrounds them – quite a few I bet.

“If I could picture the soul of the moors you would understand the beauty of the little village of Belstone for the soul permeates it as the soul permeates the human body or ether of the natural world. Possibly its silence is the most salient feature, the silence thrown into relief by the little noises of little pursuits. The voices of the air, of the insects, of the wavering trees, the breeze-haunted heather, which we speak not in less silent places, are full and rich, and great of meaning. By silence I do not mean more negation of sound, but that great fullness which the late Laureate realised in the passive sea: “Too full for sound or foam.” The brawl of the Taw reaches far on the listening air. Indeed Belstone, quiet, sturdy, breeze-brushed village, standing close in passive resistance to the wide winds that blow in from the broad Atlantic and wanton over miles of moor, has that appearance, that suggestion of listening in pre-eminence , which is characteristic of all moor borderland villages.

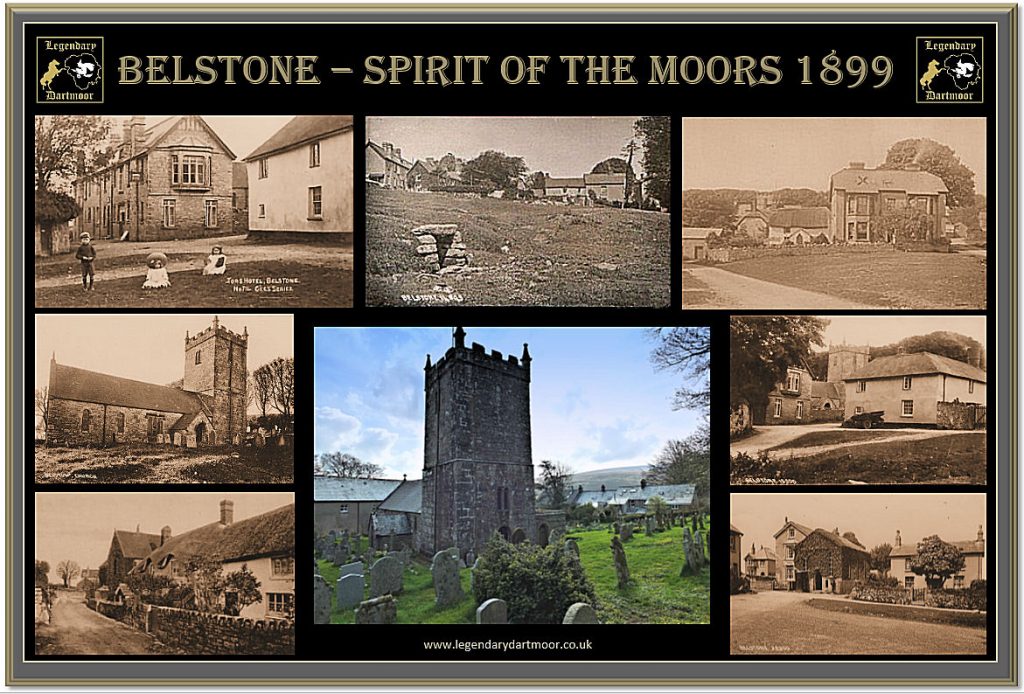

Belstone is not a large village. I supposed three or four hundred human beings would be an outside computation. I made no enquiries as to statistics, for all statistics seemed out of place in a village that inspired greater and deeper and less easily explained thoughts than dry unimaginative statistics. It is high – one is nearer the sun and the stars at Belstone than at many places – and the village has caught the quiet serenity of the heavens. There is a steep road winding by the Taw, now in summer slipping somnolently with soothing murmur pass the big boulders of its bed, standing out nakedly in the sunlight, but in winter a loud persistent torrent, tearing at the rocks impetuously. It winds, following the bank from the village of Sticklepath until nearly under the pretty, idyllic house of Skaigh, and then mounts laboriously to the little moorland village perched high on the bank (??? suggested it’s flowing backwards). Houses are springing up in Belstone but in the manner of their uprearing every man has followed out his own ideas and inclinations, and the result is a delightful irregularity of edifice and road. You come across odd corners, little waste spaces of green appropriated by geese, you turn and twist in your perambulations with the uncertainty of a hare hard pressed, you see cow sheds, stables, and houses in an mazing jumble of picturesque incongruity, and you learn to love the turnings and uncertain ways with the love that a man feels for the inanimate. Through the village and up a hill that is stony and worn with the rains you come to the moor spreading out on the left, on the right, everywhere, and culminating in purple tors for the most part, crowned withy rough granite piles of stone like play castles of dead giants. Here in the crevices of the rock, sheltering under the rudely strewn stones, are whortleberries with their rich purple fruit, and the heather spreads around in an infinitude of purple, giving labour to countless bees who sing a full hymn of gratitude during the long, hot, golden hours of their work. That sound, the singing of insects is marvellous. It steals upon the air insistently. It seems fraught with many secrets, it is alluring, soothing. beautiful.

On one evening of our short stay we went to the summit of the nearest tor. It was a still evening with the stillness of the cool air after a more than usually hot day. Then we watched the quite grandeur of the sun as it slowly sank at the back of darkening hills. It was one of the most beautiful things I ever remember seeing. At first the sky was all golden – a mist of sheen that stretched arc-like upon the breast of the sky. Into this great scheme of gold worked other tints, gradually, slowly deepened and deepened, rose pinks, touches of purple, reds lying on the ground of gold. The shadows grew longer on the tors, and deeper; the tors standing against the golden sky toned more richly, deepened and deepened, the sky flushed more and more until at last the great golden globe hid itself beneath the head of the giant tor, and there was only the afterglow. Into its pale yellow light dawned the greys of coming night. The light faded, slowly, very slowly, into the mellowness of twilight. Long, lingering twilights there are in Belstone; hours when the world seems to be saying vespers, and the over-weary labourers of the fields are going home. That night, however, the fields called for longer hours, for in some of them the harvest of the grass was being garnered into ricks. There is something very picturesque in the labour of the fields. I have seen the ploughing, the patient toil of horses, and the grinding of man’s hand; I have seen the sowing when the heart of man gives to the Mother Earth his hopes: I have seen the harvesting when the earth repays and I know not which is the best sight, not one whit. We saw the last load drawn to the rick; we saw the burden of hay forked into place and disseminating its heavy pungent odour upon the air, and it was something worth the seeing, something to carry in remembrance, for it seemed a link between the ages. Man in the beginning was born to labour in the fields, and the labour goes on today; and there is something grand in the patience, the strength, and the quiet endurance which builds up to the crown of harvesting.

There is a church in Belstone and a chapel. To the church there is attached an ill-kept God’s acre. In this the forefathers of the hamlet sleep not a whit less soundly for the presence of long lank grass furrowed by strange inquisitive steps that wave over them, or the raiding fowls that spread themselves abroad over Belstone. Ill-kept though it be and rank of grass, there is a charm in the little garden. The rusty iron gate, the plain grey granite headstones, the simple legends engraved with their brief records of lives worked out in uneventful toil, these are good things for they tell of the simplicity of life, which is a far greater thing than the fever and unrest of the city. To great ages do these moorland people attain, and it is curious to note the reference of the same name. The villagers are apparently bound to their village. They are born, live their lives, and they sleep where the moorland breezes can speak to them.. I found myself wondering whether they could read the secrets whispered in very low hushed through the swaying grass, when the wind sought an entrance over the low walls. So quiet and peaceful, and yet so far from monotony is the village, that I wonder not at the length of age the villagers are blessed with, but that they should die at all. One meets old people everywhere. One sturdy old man, trudging manfully over sun-dried dust, and through a heat that was great even in the freeness of the moorland air, told me that he was in his eightieth year: “dree munths younger nor the Queen,” yet he was still working, still full of life, still clear of memory. He told me anecdotes of Okehampton when six coaches a day rolled through its echoing streets and the era of steam locomotion still slumbered in the brains of me.

In the still of one afternoon, after much brooding of nature, and the banking up of heavy clouds, a thunderstorm burst over the village, and deluged the fields, and swelled the brawling rivulets, the Taw and the Okement. I never witnessed a grander sight. For over an hour the lightning played all around us, and the thunder was deafening. I sat out under the small portico that ran the length of our house, and watched it streak the house in living blue. So how can we complain of monotony in the country? There is no such thing. Monotony is to be found in cities, certainly not in a moorland village. Dr. Black, of Cockington, has founded a sanatorium at Belstone and the days of the patients – or rather convalescents, for they look anything but patients, once in the embrace of the moorland breezes – are full of interest. An inmate of his house assured me that one might write another book, and call it “A Window in Belstone,” and I am fully assured of the possibility. It is a fact to be known that such a place, so full of bracing air as Belstone is near to Torquay. I live in the hope of making yet further acquaintance of a village so set round with beauties.”

The Torquay Times, August 4th, 1899.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor