I came across these reminisces of a family holidaying on Dartmoor in the 1870s. The family consisted of the husband Ronald, his wife Cecilia, their son Billy and the horse Phoebe Junior. As you read it there are various remarks about their experiences that makes you that that maybe things haven’t changed so much over the centuries. As always I make no apologies for reproducing the piece as it was written as I think the original words of the author creates authenticity.

“There could hardly be a more picturesque situation than that of Chagford, though the town itself is, if I may be excused the truism, “towny.” It has a newly-built market-place, which it at once judiciously shut up,* the townspeople, I suppose, preferring the alternative of no market-day and silence. This, I thought, showed a candid and open mind in the townspeople,—the power to confess and repent promptly of an error being unusual on the part of municipal bodies. The churchyard, immediately opposite our inn, which commands a beautiful view over the valley of the Teign, is the popular promenade and meeting-place of the town. There go the perambulators, and there congregate the men.

Stately trees give it shade. Crowds of white butterflies haunt the place, as though to supply the favourite emblem of immortality. There seemed to be a close alliance instead of a natural antagonism between the Churchyard and the Inn; for the inn was not noisy, and in the churchyard there was no gloom. The scenery around was most lovely. By twenty minutes’ climb behind the inn you may reach the top of one of the many “tors” into which Dartmoor swells, and command a lovely panorama of rolling moorland, pastures re claimed from the wild, and distant faint blue hills. Antique granite piles crown half the heights around, adding greatly to the picturesqueness of the effect. And the valleys are not mere depressions in the moorland, but often romantic wooded glens, like that of the so-called parks, Gidleigh and Whyddon, which are not parks at all, but wild glens, where the Teign rushes through boulders as grand as those which stud the bed of the Wharfe at Bolton, or that of the Dove in Dovedale. The old thatched Mill, with its great water-wheel, in Holy Street, as it is called (in Gidleigh Park), is the paradise of artists, —and they do not neglect it. Still more wild and sequestered is Whyddon Park and its neighbourhood, where the Teign suddenly enters one of the most unique and rugged little gorges which I ever saw. It has a sort of toy sublimity about it, if I may be permitted the paradox, resembling one of the grandest Scotch glens where a river runs between bare and steep though rounded mountains, if this were seen through a reversed telescope so as to dwarf its scale. These were indeed but dwarf mountains, which, under ordinary circumstances, might be climbed in five minutes, by which the Teign was bordered, but so bold and so bare of everything but burnt-up grass and prickly gorse that they, and the great granite boulders through which the Teign sparkles at the bottom, give an effect of grandeur and confusion far beyond anything that the minute scale of the whole would warrant. A pertinacious desire seized me to see a certain “Logan-stone” in the bed of the stream here,— in other words, a granite boulder which a short time ago was a rocking-stone, but which has now got so silted up with sand that it rocks no longer,—and as we approached the river on the side on which there was no path, I had to get Cecilia and the dogs through the stream by fording. Even Cecilia, however, found it far from unpleasant, in that warm summer’s evening, to paddle in the clear brown water. You seem to make the scenery more your own, to enter deeper into the heart of it, as you get rid of shoes and socks, and feel rushing round you the very water which is on its way into the rocky gorge at whose mouth you stand, for here the Teign passes abruptly from broad and smiling meadows into a narrow cleft between the round, bare hills. We reached the Logan-stone, only to find a great stone oddly-balanced on a small one in the middle of the solitary stream, and a warning to fishers to beware of fishing—I suppose without the owner’s leave— painted in large, black letters on it, to my great discomfiture, not because I wanted to fish, but because it introduced various unpleasant reminders of proprietors, magistrates, and game-laws into the heart of that wild scene. Then what a climb we had up the side of the hill! It was not the mere steepness, but the glassy slipperiness of the sward, and the prickliness of the gorse at which you caught to hold your own, which made it so difficult. Cecilia would not trust the dogs to themselves, as they were keen after the rabbits, nor to me, from a general distrust of my vigilance, so they dragged her about whithersoever the scent of the rabbits took them and the sward gave her no footing, and the gorse pierced her gloves, till at last I found her, prostrate and wounded, at the very edge of the summit, crying out that the dogs were dragging her back into the abyss. Safely landed, however, on the north-western boundary of the ravine,— which is called Huns-tor, and which is strewn with the same grand fragments of granite which everywhere make the scenery of Dartmoor recall to us the age of stone,— what a sunset view we had for our reward! The opposite opening of the ravine is covered with gnarled oaks, and with huge mossy rocks, like those on which we sit. Eastwards the Teign winds away into the solitary gorge with an effect as if it were running up hill; and west wards Dartmoor rises in a series of hills, on all of which huge granite cairns break the line of gold and crimson sky; delicate pink cloudlets float about in the air above us like fragments of an interrupted dream, and as they

turn pale at last we reluctantly leave our delightful resting-place, and plod back to Chagford beneath a starlight as brilliant as that of the tropics.

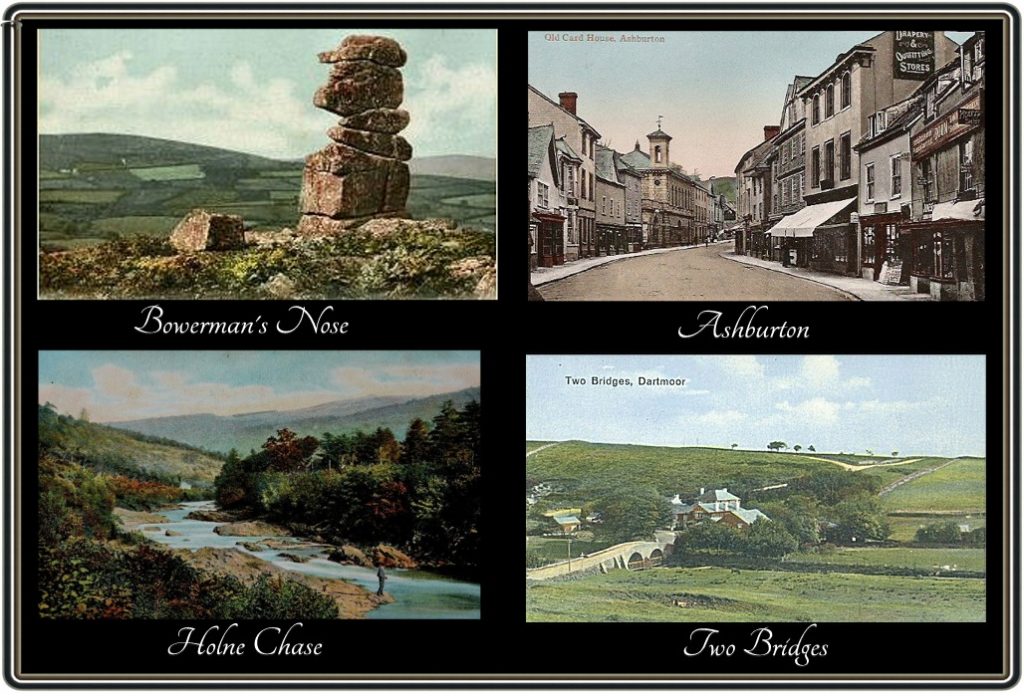

The only fault of Dartmoor to the visitor is that you find it very hard indeed to establish yourself upon it. The towns are not the places you would voluntarily choose; but the only inns where they don’t make difficulties about keeping you are in the towns. In the moorland villages, where you would like to stay, the landlords are kindly and hospitable for an hour or two, but resolute not to have you above a single night at most. At North Bovey, for instance,—most picturesque of Devonshire villages, built round a group of oaks and mighty ashes, and with a magnificent old weather-beaten church watching over it,— we persuaded a village land lady to keep us for a night, but when the morning came, kindly but firmly she insisted on our departure, under penalty of remaining without dinner and without attendance, We were most reluctant to go. I was somewhat unwell, for the previous night,—”A night in which the bounds of heaven and earth were lost;” had blazed hour after hour with lightning; and little Billy, who had rashly swallowed a bee or wasp, and got stung in the throat, had allowed us little sleep, having been literally what the transcendental lady in ” Martin Chuzzlewit” felt she should be, if she dwelt long on the enigmas of life,— a “gasping one,”—through all the earlier part of the night. But go we must. Firmly,— not peremptorily,—we were ejected and sent on to Manaton,—an island green with a granite boulder on it, and another equally picturesque church watching over it, flanked by a yew of vast dimensions, where another negotiation of the same kind began. “We might rest there a bit, and lunch, and then try a farm-house about half-a mile on, but they did not take staying visitors.”—” Had they no bedroom ?”—” Oh yes, but they were not accustomed to staying company, and they never had fresh meat.”—”Well, but if we agreed to bacon and eggs ?”— ” Well, they were not anxious for staying visitors.” And all this was so pleasantly said, and with such obvious friendliness, that it was impossible to feel offended. At last the host interceded with his wife that we might stay one night, and never did we have pleasanter accommodation or better-prepared meals. But the next day, again, mildly but positively, we were dismissed; for Saturday night and Sunday were coming, when our room would be much more useful than our company. On we must go. It was a pity; for Dartmoor is not really to be seen from the towns, and Manaton is one of the finest situations for really entering into the grandeur of its scenery. The most characteristic of its cairns,—the one called Bowerman’s Nose,—a great pile of granite, the top of which has been worn away by many a blast into the shape of a rude becapped Hindoo idol with a mighty nose,—is within a mile of Manaton, on the wildest part of the moor. Numbers of almost equally picturesque cairns surround it, within a circle of a few miles. Here, as you approach, there seems to be a council of Scandinavian Gods, Thor and Odin and their compeers, sitting in grand divan. There, again, the boulders seem to make up the ruins of a mighty castle. In another place you see in the distance what resembles the wreck of an Egyptian pyramid. And for miles and miles between them the autumn gorse spreads its rich and fragrant sea of yellow blossom, interspersed at rare intervals with a band of purple heather,—Rippon Tor, for instance, has such a grand zone of imperial purple round it,—while here and there a scarlet-breasted stone-chat is sunk in reverie on one of the boulders, or a plover hovers above you trying to divert your eye from the neighbourhood of its nest. It was in such places as these that we wanted to stay ; but only in places like Chagford, Ashburton, Tavistock, and Okehampton could we really abide as long as we liked, and there we were not on the moor, and in some of them at a considerable distance from it.

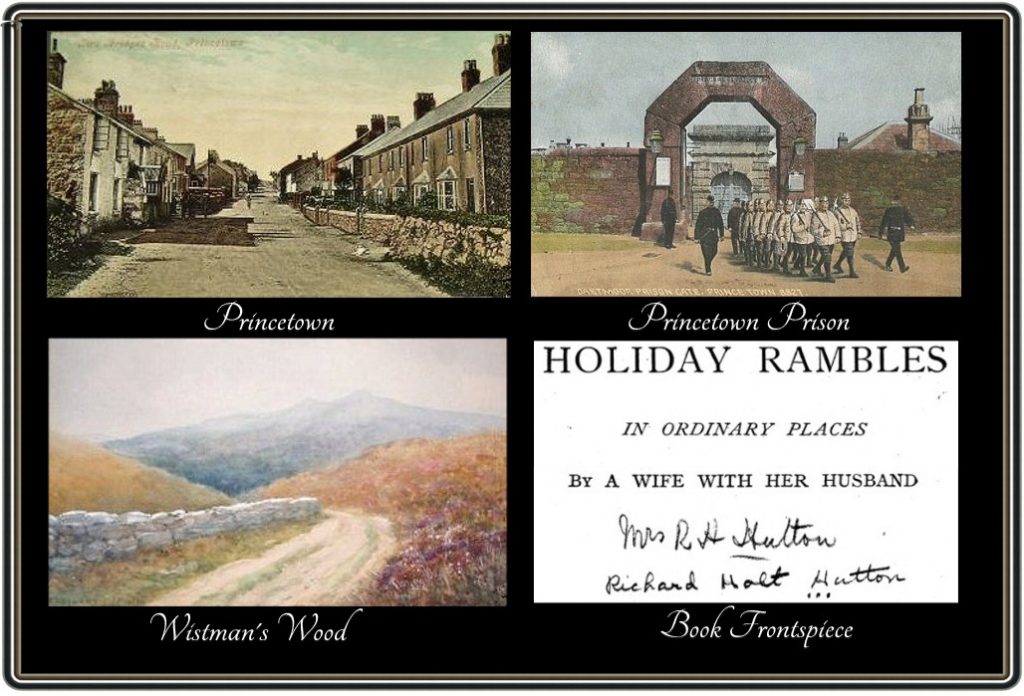

Still, at Ashburton,—where we found the perfection of an inn, with an old garden, and a thirty years’ gardener devoted to his flowers, and where we met friends of congenial tastes, who had frequent bulletins of the condition, of a dog and a sparrow, both of high intellectual development, and who could enlighten our ignorance as to the different species of fern which crowded the deep-sunk lanes,—Phoebe Junior and we greatly enjoyed our stay, though Phoebe Junior never had a harder task than that of drawing us through Holne Chase and over the moor from Ashburton to Two Bridges and Princetown, where the road climbs for at least six miles, and climbs up roads so stony as well as so steep that sympathy with Phoebe Junior took away much of our pleasure in the magnificent views of the romantic windings of the Dart. Steadily she toiled on, with her master at her bridle and a kind mistress scotching the wheels from time to time, that she might rest on the toilsome ascent; hill after hill lay behind her, and ridge on ridge of moorland before, till at length Dartmeet bridge was crossed, and as the sun hid himself behind clouds, and a cold wind rose, and the beautiful shapes of the moorland ridges disappeared and were succeeded by long, flat, desolate stretches, we approached Two Bridges and Princetown, and that gloomy region where sentries pace about the road, and the prison bell rings out from time to time the sad succession of the great prison’s regulated hours. At Two Bridges, which is the advance-guard of Princetown, we passed the dreary lees of a yesterday’s fair,—a desolate booth or two, where boys were still paying their penny for a shot, and small children buying unwholesome sweets. Within a mile, in a desolate ravine to the north, lies the weird little dwarf oak copse, haunted by vipers and penetrated by such deep gullies that it is said you may sink suddenly to the neck if you venture within the network of the gnarled and moss-grown branches, which is called Wistman’s or Wiseman’s Wood. Not an oak exceeds, I think, ten feet in height, and most are but eight feet or six. Every branch of every tree that we saw was cushioned with the softest moss and lichens, so that the air of hoar antiquity about the dwarf wood is inexpressibly striking. When the mists are swirling about the ravine, as they often are, the weirdness of the spot must be most oppressive. It is just the place for an escaped convict to hide himself, and after a few hours spent with the vipers, and of listening to the sighing of the wind in these prehistoric oaks, to give himself up voluntarily, out of sheer preference for the prison. Yet under the sunshine, when the herds of Dartmoor ponies are galloping about and dashing down with one consent to the stream to drink, the drops from the spongy ground flashing up behind their heels like diamonds in the sun, and the stone-chats are flying from one block of granite to another, and the hawks are hovering in the sky, on the look out for an imprudent bird, the weirdness of the place can look almost attractive.

Not so Princetown itself, though it seems to be regarded as a sort of watering-place, and two or three large fishing and pleasure parties were lodging there. It certainly is the dreariest of bleak neighbourhoods, surrounded by formal patches of land cultivated by the prisoners, studded with the various signal-posts whence the escape of a convict can be at once announced to other stations, and generally enveloped in an atmosphere of fear and gloom. Even the houses are tarred outside in so slovenly a fashion that they seem to have black, gigantic, dripping fingers closing on them from above, with the view of snatching them away to the bottomless pit. The inn was full of the dreary pleasure-parties when we arrived, and the landlady had to get us a bed out, which, as it was

both wet and cold, was not very delightful. However, she said it should be clean, but when we arrived at the lodging at half-past ten, we found that the women of the house had retired, and that the sheets had certainly been used some dozen times before. There was nothing for it but to pull them off and wrap them up in a corner of the room. Even the floor was so doubtful that one made islands for one’s self to tread on in it, and for blankets we used our own wraps. The dogs slept well, and so did Cecilia. But for me, I confess,—partly, perhaps, because I had got nothing but a bank or shoal of some ridgy substance which appeared to be granite, in the so-called mattress, to sleep on,—the night was as weary as it was cold. Confused pictures of “the Claimant” ” retiring behind a sapling” to weep,—they say that he is in distinguishable in size from any other prisoner now, and that the sapling might really hide some of him,— voices asking me if “I should be surprised to hear ” that there would be an explosion of paraffin gas shortly before sunrise,—a horrible paraffin lamp diffused its odour through the house,—vague remembrances of the scene in the Essex marshes in ” Great Expectations,” where Pip meets the convict, and is threatened with fearful consequences if he does not stock his boot with bread-and butter early in the morning,—and a ghastly impression that a jury of fishes, with a great flatfish for a judge, had found me guilty of a frightful act of vivisection,— rendered my sleep that night certainly a great deal more disturbed than that, I should hope, of most of the convicts in the neighbouring prison.” R. Holt Hatton. 1877. Holiday Rambles. London: Daldy, Ibister & Co. pp. 310 -319.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor