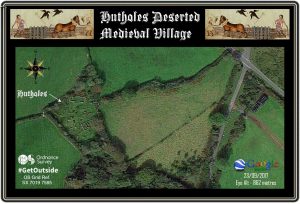

Nestled between the bosom of Rowden Ball and Dunstone Down is the ‘deserted medieval village’ of what today is known as ‘Hutholes. The term ‘village’ is probably doing the settlement huge injustice as once it was an ancient manor dating way back into the long-lost mists of time. If ever in Princetown drop into the visitor’s centre where you will find a fantastic piece of artwork which depicts what such a medieval settlement would have looked like, it really sets the stage for a visit to Hutholes. Admittedly this is not the easiest places to find and there is only an old weather beaten fingerpost pointing to it. Probably the easiest way to get there is take the B3387 to Widecombe-in-the-Moor and drive through the village and just after passing the school turn up right onto Southcombe Lane and follow it up and across Dunstone Down until reaching a crossroads. Drive/walk straight over (if visiting by car and if possible verge) of what is Hutholes Lane. Walk downhill for about 200 metres and you will spot the fingerpost in the hedgerow on the right-hand side – OS grid reference SX 7019 7585.

The consensus of opinion tends to be that Hutholes was the old manor of Dewdon which originally appeared in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Depdona. Firstly the place-name, Hutholes was at one time one the field name in which the settlement lies. In 1963 a report on the ‘Abandoned medieval sites in Widecombe-in-the-Moor’ was published in that year’s Transactions of the Devonshire Association. It noted; “South Rowden or Hotholes – The small deserted village lies in an acre of waste ground known as Old Walls… this was the site of a holding known as South Rowden…” The report then goes on to say; “As the buildings are all comparatively small, this may have been a villein’s settlement near the manor of Dewdon in which it lies. This site is to be surveyed in the near future and an excavation arranged to obtain dating for its period.”

As noted above Depdona was the name of the manor which appeared in the Domesday Book which over time mutated into Dewdon. The English Place-Name Society suggest that the name has two elements – deaw meaning dew and dun meaning hill thus giving a ‘hill where heavy dew occurred’. According to the Domesday Book in 1086 the settlement consisted of 19 households comprised of; 18 villagers, 6 smallholders and 14 slaves. This would have been considered to be a medium sized settlement at the time of the record. The lands associated with the manor were as follows; 13 plough lands (lands for), 5 lord’s plough teams, and 7 men’s plough teams. Other resources along with the plough lands were 1 Lord’s lands, 15 acres of meadow,50 acres of pasture and 50 acres of woodland. As far a livestock numbers go, the inhabitants were tending; 8 cattle, 159 sheep, 42 goats and 1 cob horse. In pre-conquest times the manor belonged to a man called Alric and post-conquest it was given to William of Falaise whose tax assessment for the manor in 1086 was 1.5 geld units which it appears he got off quite lightly in comparison with other manors. Along with Dewdon William was also gifted other manors on Dartmoor, these being; Holne, Stoke, and Dean Prior, along with 14 various other manors in Devon.

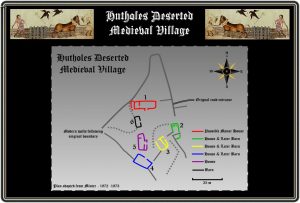

It was a local farmer, Mr. Hermon French who first alerted the presence of Hutholes to one Mrs. Minter. It was she who eventually began the excavation mentioned in the 1963 report which duly took place along with that of the Houndtor and Dinna Clerks between 1961 and 1975. Her excavations revealed the remains of a lengthy sequence of buildings. It was also stated that lines of stake-holes were found lying underneath some of the ruins of 13th century buildings suggesting earlier structures. The buildings of the last phase of development are what we can see today and comprise of a manor house, a three roomed longhouse, a barn for drying corn and three other structures likely to be outbuildings. the Pastscape record for Hutholes reads; “The small deserted village of South Rowden or Hotholes (Hutholes) lies in an acre of waste ground known as Old Walls, on Dockwell farm. The ruins of six buildings were the remains of a more extensive Medieval village. The remnants of a narrow entrance lane can be seen leading from the Grimspound to Widecombe road and passing through the site. Excavation disclosed overlying sequences of turf-walled buildings replaced by stone walled structures comprising the manor house, a three-roomed long-house, two single-roomed dwelling houses, and two barns, one of which was possibly for drying corn. The stone-walled manor house was an imposing building 51 feet by 20 feet. After partial demolition in the early 13th century it was replaced by a similar building, 44 feet by 14 feet. The stone-walled long-house replaced the last turf-house and was also of two periods. Pottery suggests that the stone house was occupied in the late 12th and 13th century. The beginning of the site is provisionally ascribed to the early 11th century. Classed as a well preserved site.” – see page HERE. During the excavation of the manor house (number 1 on plan)various sherds of pottery were found and were identified as coming from a cistern a cooking pot and two yellow glazed jugs. The location of these finds suggested that the room was used both for storage and a sleeping area. In addition a well-worn long-cross penny was found in the north east corner of the byre and was minted between 1253 and 1260. This would imply that the house was destroyed sometime in the late 13th or early 14th century. In the house just to the south of the manor house you can still see the remains of a cooking pit which lies just infront of what Minter identified as cupboards. Sadly the drying ovens in building number 2 are no longer distinguishable thanks to the modern walling.

What lead to the final abandonment of the settlement? It has been suggested that around the mid 13th century the climate gradually deteriorated. This would have been a gradual change with some years of plentiful harvests interspersed with disastrous ones. At first this didn’t present too much of a problem and measures were taken to overcome failed harvests. The evidence for this comes in the shape of the corn drying kilns which allowed for salvaging wet grains. As the years rolled on it would have become harder and harder to provide food especially in light of the deteriorating weather and temperatures. It is very unlikely that Hutholes would have been abandoned in one go, some people would have tried to soldier on due to old age or sheer determination. On the other hand other folk would have moved on as soon as times became hard. Either way it has been estimated that by the middle of the 14th century all land on Dartmoor above the 1,000 ft. contour level became incapable of sustaining adequate living conditions and so led to the abandonment of settlements such as Hutholes. Although the original manor of Dewdon became abandoned the manor itself lived on in the form of Jordan Manor which is located roughly one kilometre to the south. The actual place-name of Jordon is simply a mutated form of Dewdon.

Phenomenology -mindscape, call it what you like but Hutholes more than caters for both. Although I had seen pictures of the place I had never actually visited there so I had no real expectations. But on opening the roadside gate it was easy to imagine stepping back in time. The short stroll through the various moss covered trees was to the accompaniment of orchestral birdsong which immediately had a tranquil effect. The old enclosure walls were clothed in a variety of mosses and lichens and it seemed that out of every gap some plant or other was struggling to make an entrance. The very air was laden with the aromas of fresh early springtime subtly infused with the last remnants of winter decay. On the left of the path a small stream gurgles through the dense cover of trees and shrubs as it travels to meet the West Webburn. Then suddenly the wide grassy expanse of the long deserted village bursts forth, at first glimpse it appears as a jumble of low walls but gradually the old houses take their form. A quick glance at the interpretation board adds context to the site and suddenly a magpie erupts into excited chucks and clucks as if welcoming one to explore. Straight away what was the manor house beckons forth and on entering the strange feeling of deference is overwhelming, it’s akin to that of walking around a National Trust stately home. Having owned so many manors one wonders if William Falaise ever spend much time here or were they just fleeting visits? The only occupants today are a young gorse bush and a patch of reeds who have taken up residence in what at one time would have been the livestock byre. Oddly enough it’s not hard to imagine the sweet, sweaty smell of cattle intermingled with the acrid ammonia stench of urine. Then a polite but commanding voice whispers from the long and distant past and seems to say; “thanks for your visit but now its time to leave,” and so not wishing to overstay one’s welcome a hasty retreat is made. So with head bowed it was time to call in on the neighbour who was much more accommodating. Sit down a while and ponder what the scene would have been back then. A hand seat is provided which would have been the cupboard and so perching on this it’s not hard to imagine the long dead inhabitants going about their daily chores. The whole house is shrouded with a dense cloud of wood smoke wafting around the rafters. Immediately infront of the cupboard is a flat slab of rock covering a small, black hole in which the family’s dinner would be bubbling away, the smell greasy smell of mutton and earthy root vegetables emanating from it. On leaning back something scratches my back which turn out to be three young foxglove plants – would such an intrusion have been allowed way back then? Would the medicinal properties of those plants been known to the inhabitants of yore? Then a flood of questions come rushing through the mind, who, what, why and when. The most salient one being what would have it been like to finally realise that it would be impossible to continue living in your home? Clearly such a sad situation is nothing new and unfortunately for whatever reason still happens today. But in this case the over reliance on limited food sources clearly demonstrates what can happen when they no longer become available to a static society. Before the advent of settled agriculture humans survived by hunting and gathering so if one food source became scare they simply upped sticks and moved to another more productive area. Whereas once a static agrarian settlement had been established with permanent houses, fields etc it became much harder to simply move on to pastures new. It would have been only when climatic deterioration became so bad that folks simply had no choice. Sometimes places of abandonment and decay tend to have an dark atmosphere surrounding them but Hutholes to me seemed a very peaceful place with distinct echoes of the past.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

I visited Hut Holes today, having been meaning to do so for some years. Your interesting article has added hugely to my limited knowledge of the site, thank you.

I visited Hutholes today having read about it in Paul White’s Medieval Dartmoor booklet. Your brilliant article made the visit so much more enjoyable, as we imagined life in the village all those centuries ago. I’m surprised it’s not mentioned on the OS map. It’s a hidden gem! Thank you.

April 2021 one of my favourite places on the moor- sit and experience the peace of an ancient site all around you. Copious water below and a sheltered sunny slope. Never met anybody else on site.

Your article so helpful and interesting made it come alive. Thank you