“About them stretched square fields, off some of which a harvest of oats had just been shorn; while others were grass green with the sprawling foliage of turnip.”

Falcon Farm – Orphan Diana, Eden Phillpotts

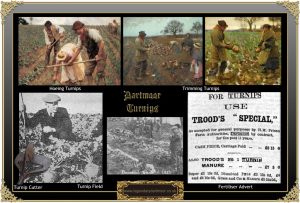

For anyone that has seen the now famous Warhorse movie they will recall the Dartmoor scene where ‘Joey’ bravely ploughs a field in which turnips were to be planted. But although it is uncertain exactly when the turnip was introduced there is evidence of it being eaten in Roman times. On Dartmoor the turnip or turmit as it is known has long be used to feed both man and beast along with its later use as a break crop.

In the 1730s Viscount Townshend introduce the revolutionary new method of crop rotation which became known as the ‘four field system’. This basically involved dividing the available arable lands into four, one quarter would grow wheat, another clover , a third oats or barley and the last turnips or swedes. This system had the effects of restoring nutrients to the soil as opposed to simply leaving it fallow whilst improving yields and providing winter fodder crops. This practice slowly became standard policy on many farms and earned the Viscount the nick-name of ‘Turnip Townshend’.

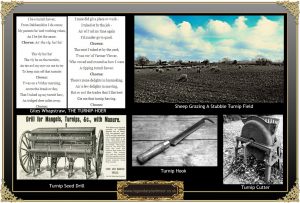

But in Devonshire things move slowly and in 1796 Marshall notes the following; “Notwithstanding the unhsubandlike manner, in which Turneps are still cultivated, in this District, it is more than half a century since they were introduced into field culture:- a strong evidence of supineness (lethargy) of the Devonshire husbandman.”, he further adds: “The species, various; but not excellent. The proper method of raising the feed does not appear to be understood, or is not attended to.” It was Marshall who introduced the practice of sowing turnips after a grain crop instead of sowing onto grassland. The process of growing turnips involved firstly tilling the soil, this was done by ‘velling’ or ‘skirting’ (forms of ploughing) and burning. The seed was then sown at the rate of one or two pints per acre in July. In theory once the crops began to grow it was necessary to hand hoe the weeds out on a regular basis but according to Marshall this was a practice much neglected in Devonshire. He notes; “This phenomenon struck me forcibly in travelling between Exeter and Plymouth in the latter end of December 1791.” Once fully grown the turnips would then be fed to grazing cattle or sheep or taken back to the farm to feed housed beef cattle,. – Marshall, pp. 194-198. In 1808 Charles Vancouver published his ‘General View of the Agriculture of Devonshire’ in which it appears that turnip growing had not improved. Still there was little attention paid to tillage and weeding. He does indicate the varieties grown, they being; the white loaf, green or purple types and that an acre of “good unhoed turnips is usually valued from 50s to 3l. (£).” – p.189.

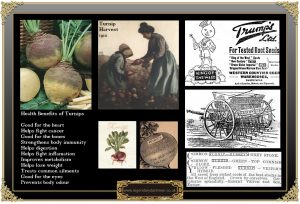

In 1834 The Farmer’s Magazine noted the following with regards to the Dartmoor turnip crops which shows things were on the up as far as cultivation went: “Turnips never were finer, and I am glad to see that many active and industrious farmers, notwithstanding the gloom which pervades agriculture, have tilled many of their wheat arishes to turnips, which (with the favourable weather for their growth) will produce half a crop, and continue good until late in the spring.” By the late 1800s the varieties of turnip own had grown no end and the seeds included; Imperial Green Globe, Devonshire Grey Stone, Purple Top Mammoth, Lincoln Red, Stubble, and Pomeranian White, in 1894 all costing eight pence a pound. As a guide to the cropping yields on Dartmoor Tanner mentions that in 1852 and 1853 a farmer called Fowler from Princehall won the South Devon Agricultural Societies award for the heaviest white turnip crop which weighed in at forty three tons, eight hundredweight, one quarter and six pounds per acre. With regards to production he comments: “The general plan is, to hand-beat and burn the turf which remains from the grass seeds sown, and the plough the land 3 or 4 inches deep, in preparation for turnips. Having a scarcity of manure, and little cash to expend in the purchase of a necessary supply the farmers rely on the ashes obtained from burning the turf for producing the desired crop of roots, which varies from 5 to 10 tons per acre. The turnips are drawn in November, and stored in pits dug in the field where they are grown; thus in a field of 10 acres, there will probably be fifty pits; and in this manner they are preserved until consumed by sheep or cattle. After the turnips are eaten, the land is ploughed for oats, and with this crop the land is again laid down in “seeds.” – Tanner, p.13. As can be seen from the fertiliser advert below actually referred to Mr. Fowler as a testimonial for there product such was his regard for growing turnips. According to William Crossing writing in the early 1900s it appears that although the farming improvements made at Prince Hall by Mr Fowler were unsuccessful he seemed to do well with turnips. But contrary to general opinion he went on to say that whilst he grew the largest turnips ever seen on Dartmoor but there was one problem, they were: “Proper gert benders, zure nuff – but most o’ mun was holla.” – p.113.

Once the crop had been sown there were several threats to its growth, firstly on Dartmoor the weather could be a damaging factor but not a lot could be done about that. Secondly weed growth could choke a crop and by the mid 1850s farmers realised that weeding was a vital if not labour intensive operation. Thirdly insect pests if not treated could decimate a crop from the early leaf stage onwards. The main culprits as far as the leaves were concerned being the Turnip Beetle or Fly, the Black Caterpillar or Nigger and the Turnip Lice. Then with regards to the roots there was wireworm,

There was a whole variety of ways of these pests and in the case of the Turnip Beetle included burning, folding sheep on the field and dusting. Dusting was said to be the most popular but by its method of application not so popular. Whatever the crop was being treated it had to be done early in the morning whilst the dew was still on the crop and very much depended on the enthusiasm of the farmer. It was said; “The farmer accustomed to be ‘up with the lark,’ and to walk abroad over his fields ere the sun dries up the dew, would likely see that this dusting process was performed at a proper time, and under circumstances calculated to ensure good results. But the slothful, lie-a-bed farmer, who seldom appears in his fields until after breakfast, must depend wholly on the faithfulness and devotion of his work people as to the proper performance of those important matters.” So the idea of running a flock of sheep through the crop whilst the dew was still down worked on the principle of them stirring up the dry soil which then stuck to the dew thus coating the leaves. The same principle applied to dusting except it involved physically applying the dust. There were several substances used in this process such as; ash, flour of sulphur, dust swept from the highways, and powdered lime. One concoction some times used was 1 bushel of fresh as from a gas works, I bushel of fresh lime from the kiln, six pounds of sulphur and ten pounds of soot which would be enough to cover two acres. Another alternative and more applicable to Dartmoor was 2 bushels of road scrapings, I bushel of fresh lime and fourteen pounds of sulphur. These mixtures were either broadcast or applied or more effectively with a turnip drill.

With regards to the black caterpillar , again there were a few control measures such as allowing ducks or poultry to graze the field and eat the caterpillars. Alternatively to dragging a cart-rope, a hurdle or green furze over the crop thus killing the pest that way and laboriously walking the rows and hand picking the caterpillars. The turnip lice were controlled again by hand picking the damaged leaves or applying a solution of lime dust or lime dust and tobacco water. Wireworm was also controlled by walking the crop and handpicking.

Harvesting the turnip crop was a very labour-intensive operation, Olive Hockin was a land girl on a Dartmoor farm during the First World War, here is her account of harvesting turnips; “Usually these are eaten by the sheep straight off the field, or pulled and given fresh to the cattle. But this year, since frosts were beginning early, we were pulling and pitting half the field. The more we could prolong the life of the turnip into the winter the longer would our mangolds hold out in the spring, and to begin to draw on this mangold reserve, at any rate before Christmas, seems to be an act of sacrilege on the part of the farmer…. So for a time now our daily labour took us to the upper turnip fields. We pulled a patch of convenient size, threw them all to the centre, piled them up tidily and then covered them with earth, marking the field with a diaper pattern of little black mounds.

Our only trouble over that job was the unwieldy Devonshire spade we were given to use – a heavy three-cornered thing with a long slippery handle and no loop at the end, as have all Christian spades we had met before. These outlandish implements treble the difficulty of digging; the only way, as I was once shown, being to rest the handle over the knee and push with the lower part of the femur, a process that naturally produces black-and-blue bruises over one’s leg… While Jimmy continued the work, I was generally up and down with Bobby (the cart-horse), pulling them and carting them for the cows.” – pp. 126 -127.

Having once grown a crop there were two main ways of capitalising on the crop. The most common being to harvest it and then use it as winter fodder for the housed cattle which again was another labour intensive operation as the turnips had to be topped and tailed of its leaves and roots, normally done when harvesting the crop with a turnip knife (see above). Then it had to be cut up either with a hand-held turnip cutter (see above) or a mechanical turnip cutter. In many cases the Dartmoor lowland flock would simply be turned out into the crop and after crushing the turnips with a plough and let them graze. Or should a farm have sufficient land it was much easier to sell the standing crop to another farmer who would then put his flock into the crop. One such example of many adverts that appeared in the local press was a field being sold at auction on Chagford Fair day. This was a lot of two acre field of turnips which the purchaser would be allowed to run his sheep on with the proviso that they were taken off on or by the 1st of April.

It was generally said that the disadvantage of feeding turnips to dairy cattle was that it could taint the milk, one old method of removing the taste of turnip from milk or butter was to dissolve a small amount of nitre in spring water and then add a teacup full to every eight gallons of warm milk which was freshly drawn from the cow. However as Devonshire butter was made by always made from fresh cream which was thickened only by scalding this was not the case. In other counties the cream would not be scalded and was just left to turn sour naturally.

According to the Dartmoor tithe apportionments for the 1840s there are several field names that relate to turnips; Turnip Close (Widecombe), Turnip Meadow (Chagford), Turnip Plat (South Tawton) and Turnip Plot (South Brent).

Over the centuries theft was also a problem and numerous newspaper reports of various local assize courts detailed people being summonsed for stealing turnips. In many of the cases the thefts were as a result of poor folk unable to feed themselves or their families whilst others were purely for gain. Here are but a few Dartmoor examples – For instance on the 3rd of September 1848 one Thomas Sweetland was charged with stealing turnips from farmer Bawden’s field. Bawden was passing his field when he saw Sweetland drawing turnips and hiding them under his coat. At the Assize hearing Sweetland said that he was a day labourer earning eleven shillings a week and with a wife and five children to support he found it hard to get by. He was fined two shillings and eight shillings cost. In 1850 Charlotte Seymour was charged with stealing turnips from farmer Dennis’ fields at Sticklepath. He said that he had lost over a ton of turnips and had seen Seymour pulling turnips and putting them in a bag. This was not the first time she had been charged with such an offence and was sentenced to one months hard labour. In 1876 David Perkins was charged with stealing turnips from a field belonging to Dartmoor Prison. A warder was returning home when he saw Perkins beside a turnip clamp with a large bag. The warder apprehended Perkins and told him to replace the turnips and also he confiscated the bag, Perkins offered him two guineas if he would forget the matter, the warder refused and reported the theft to the Prison Governor. In light of a previous felony of stealing turf the Chairman sentenced Perkins to six months hard labour. In 1899 John Brimblecome was fined fourteen shillings at Moretonhampstead Brewster Sessions for stealing turnips. In 1903 Robert Tozer was charged with stealing six turnips from a field belonging to William Conneybeare at Holne. Tozer said that as a navvy he earned eighteen shillings from which he spent five shilling on lodgings and the rest he sent home for his wife and six children. As he was broke and starving he stole the turnips. As it was his first offence he was let off under licence. In 1914 a gypsy woman named Laura Small was charged with stealing turnips valued at one shilling and six pence from a filed belonging to Lounston Farm at Ilsington, she was fined one pound or one months imprisonment.

There is one Dartmoor story where turnips cost a farmer dearly, there was a young farmer who had a wealthy and childless landowning uncle which meant one day he would come into property and money. There was one slight problem insomuch as the young man had a tendency towards taking fancy to other people’s property, One day when his uncle had gone to market the nephew decided to help himself to some of his uncle’s turnips. Unfortunately during the process of stealing the harvest some neighbours spotted what was going on and on the old mans return informed him as to what had happened Needless to say the Uncle was none to chuffed and the upshot was that the young man was written out of his will thus leaving him without the “value of a pint“, Leger-Gordon, pp. 95 – 96.

It was not only livestock who ate turnips as in many a Dartmoor cott they were often on the dinner table in one form or another. One favourite was ‘Cream Turnip’ a recipe for which was; “Ingredients; 4 large or 6 small turnips, 3 oz. cheese, liquor, level desert spoon flour, preferably whole meal. – Boil turnips with very little water until tender. drain, slice, dice, moisten with sauce made of liquor left over and flour. Add a little milk and boil until thickened, grate cheese over dish and serve hot.”

In 2000 the University of Exeter carried out a study of Dartmoor’s agriculture and included in its land use data is a figure of 148 hectares used for growing turnips, swedes, kale, cabbage, savoy, Kohl rabi and rape. Although this does not give an exact figure of turnip production when one takes into account that the total hectarerage of agricultural land use on Dartmoor equates to 46,659 hectares then it’s obvious that very little turnips are grown today.

Crossing, W. 1990. Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor. Newton Abbot: Peninsula Press.

Hockin, O. 1918. Two Girls on the Land. London: Edward Arnold.

Marshall, W. 1796 Marshall’s Rural Economy of the West of England. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

St. Leger-Gordon, D. 1954. Under Dartmoor Hills. London: Robert Hale Ltd.

Tanner, H. 1854. The Cultivation of Dartmoor, A Prize Essay. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longman.

Vancouver, C. 1969. General View of the Agriculture of Devonshire. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor