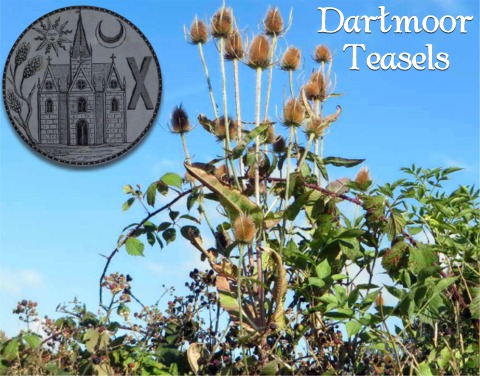

Dipsacus fullonum – alias Teasel, Teazle. Teasle, whatever you want to call it the teasel is amongst the more easily identifiable plants that occur on Dartmoor. It had for centuries also played an important part in Dartmoor’s cloth making industry.

On Dartmoor teasels can be found in moist grassland and around field margins as well as roadside verges, wastegrounds and anywhere the ground had been disturbed such as plantation clearance. Teasels are biannual plants which in their first year produces a low, basal group of leaves which can be best described as prickly and dotted with pimple-like eruptions. But it is in the second year that put on a remarkable growth spurt and the prickly stems can grow to some incredible heights and a quite capable of reaching a few metres. The leaves appear in pairs which are joined together and are joined opposite each other to the main stem. During July and August the pinky-mauve flowers emerge as large oblong cylinder shaped heads between 3 and 8 centimetres long. They begin flowering around the centre of the head and they slowly spread up and down the head, as they do the central petals drop off. The main stalk produces the biggest and more robust flower head which is called the ‘King’ whilst at the end of the main branches ‘Queen’ teasels of medium size grow along with ‘Button’ teasels on the secondary branches produce the button teasels. In the winter the seeds heads turn a light brown in colour and consist of small prickles.

Thanks to the paired arrangement of the leaves tiny pools of rainwater collect in cup and form a kind of moat around the stem. Any tiny insect that enters the ‘pool’ tend to drown in its waters and eventually their decomposing bodies form a thin ‘soup’. This soup is then utilised by the plant which has been proven to enable it to produce more seeds. Due to this ability some people have classified the plant as being carnivorous but teasels do not have the natural enzymes which would allow it to physically dissolve the dead insects itself and therefore the plant can be considered as being proto-carnivorous.

As mentioned above the teasel has played an important role in the cloth making industry which once was a major industry in and around Ashburton and Buckfast. So much so that Ashburton’s Portreeve’s seal depicts a church situated between a teasel and a saltire cross with the sun and moon either side of the spire (see below). An early description of the use of teasles in cloth manufacturing stated;

“The use of the teazle is to draw out the ends of the wool from the manufactured cloth, so as to bring a regular pile or nap upon the surface free from twistings and knottings, and to comb off the course and loose parts of the wool. The head of the true teazle is composed of incorporated flowers, each separated by a long, rigid chaffy substance, the terminating point of which is furnished with a fine hook. Many of these heads are fixed in a frame; and with this surface of the cloth is teased, or brushed, until all the ends are drawn out, the loose parts combed off, and the cloth ceases to yield impediments to the free passage of the wheel, or frame, of teazles. Should the hook of the chaff, when in use, become fixed in a knot, or find sufficient resistance, it breaks, without injuring or contending with the cloth, and care is taken by successive applications to draw the impediment out; The dressing of a piece of cloth consumes a great multitude of teazles requiring form 1,500 to 2,000 heads to accomplish the work properly. They are used repeatedly in the different stages of the process, but a piece of fine cloth generally breaks this number before it is finished; or we may say that there is a consumption answering to the proposed fineness – pieces of the best kinds requiring 150 to 200 runnings up, according to circumstances.” – The Manchester Times, February 28th, 1829.

As can be gathered from the above description the teasels main purpose was to ‘tease’ the cloth which is the English derivative of the plant’s name. As far as its Latin name goes the fullonum element means ‘to full’ as in cloth making. Dipsacus comes from the Greek meaning ‘ to thirst’ and alludes to the pool of water which collects around the leaves. Another name for the teasel used by the Romans was the ‘Venus’ Basin’ which alludes to the soup that collects in the base of the leaves and in a similar vane it was also known amongst Christians as ‘Mary’s Basin’.

Additionally the report highlights the vast amount of teasels needed in the cloth manufacturing process. Therefore it is no surprise that teasels were grown commercially in order to supply the great demand. As yet I can find no firm evidence that such a crop was ever grown on or around Dartmoor and it is a known fact that the main south western teasel growing areas were Somerset, Wiltshire and Gloucestershire. However, there was another newspaper report from 1916 with regards to a war tribunal which was held in respect of application made for exemption of military service which read; ” A novel occupation was disclosed in an application made by William Andrews, of Tedburn St. Mary (which is about 4 km from the National Park boundary.) He described himself as a teasel grower, a kind of cultivated thistle, so he said, in the manufacture of blankets and cloth, much of it for military purposes. Applicant said he and his father were the only grower of that species of plant in the county. The demand for it was great and the supply limited. They had five acres now in cultivation, and were planting another similar area. It was work that required skill and experience, each teasel having to be handles separately. The whole industry was complex. the local tribunal refused exemption on the ground that teasels were no longer essential to the manufacture of cloth.” – The Western Times, October 21st, 1916.

With regards to the teasels’ medicinal uses they are wide-ranging, latterly some people suggest that an extract made from the roots of the plant will cure the tick-born Lyme’s Disease in both humans and dogs. From a much earlier era, the famous herbalist Nicholas Culpeper suggested that; “It is an herb of Venus. Dioscorides saith that the roots bruised and boiled in wine till thick, and kept in a brazen vessel, and after spread as a salve and applied to the fundament (the buttocks), doth heal the cleft thereof, cankers and fistulas therein, also taketh away warts and wens. The juice of the leaves dropped into theears, killeth worms. The distilled water of the leaves dropped into the eyes, taketh away redness and mists that hinder the sight, and is often used by women to preserve their beauty, and to take away redness and inflammations,and other heats and discolourings.” The British Herbal, 1652, p.287. With regards to the teasel ‘soup’ there are various uses for this, for instance it was said that the liquid was good for cleansing the feet. Other attributes were that it provided relief from sore eyes and improve the complexion. There are even references to a tea made from the crushed roots which was said to be a cure for jaundice. Some of the Bear Grylls type survivalists advocate drinking the ‘soup’ when there is a scarcity of water or liquids as it is basically rainwater – yeah right, what about all the slowly decomposing insects or are they a source of additional protein?

Ecologically the teasel flowers are highly attractive to a host of butterflies, bees along with other pollinating insects and once the seed head has ripened they are a good source of food for goldfinches. They often appear as attractive border plants in garden and around ponds. It has even been suggested that once the seed heads are empty to refill them with niger seeds to further attract the goldfinches. Due to the lasting ability to retain their colour teasels are often used in flower decorations and who at Christmas has not sprayed them gold or silver to be used as festive decorations?

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor