Summer is the time of year when you can return from a day out on Dartmoor and find you have one or more uninvited hitch hikers firmly attached to your person. Depending on how soon you discover them they can appear as a small, spider-like insect or as a reddish grey protuberance about the size of a bean. Over recent years they seem to have become more of a problem and one that causes concern as it is now known that in certain circumstances they can spread to Lyme’s disease.

But how did they get onto you, well do you remember the grassy spot where you had that picnic? or that jungle of bracken you waded through in your shorts? they were just sat in both places waiting you. The little sods saw you as a buffet car that would give them a comfortable ride and a sumptuous meal. But don’t get paranoid it was not you specifically they were waiting for, any warm blooded animal would have done, from a sheep to a dog, all appear on their menu.

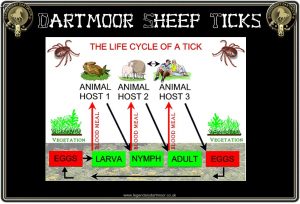

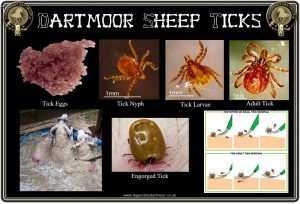

So why? Ok, in this instance we are talking about Ixodes ricinus, and to answer the question it is as well to look at their three stage life-cycle. As with anything it starts with the female laying eggs, about 2 – 3,000 of these are laid on the soil – The eggs hatch and turn into six legged larvae which are between 1.3 and 1.5 mm in size. These then crawl up the nearest blade of grass or frond of bracken etc, here they calmly sit and wait. If they are lucky, host number 1 (small creatures such as rodents, rabbits or birds) comes sauntering along and brushes against whatever they are sat on, the larvae then moves onto the host. Once safely ensconced it will then firmly attach itself to the skin and start feeding on the host’s blood, once fully engorged it will drop off the host and molt into the nymph stage.

Once developed the nymph has eight legs as opposed to the larva’s six, it then repeats the process of looking for host number two. Again these are the smaller creatures such as rodents, rabbits and birds, but can also include humans. When the larva has engorged itself on the host’s blood it drops off and returns to ‘earth’.

The larva then develops into the adult stage, by now females are about 3 – 3.5 mm in size and the males stack up at about 2.4 – 2.8 mm. It is known that the adults sense their hosts by what is known as Haller’s Organ, this is a sensory structure which is highly sensitive to humidity and odours and is located on the first walking leg. This stage is the only one to have such a ‘seeking’ ability. This time the adults look for larger hosts such as sheep, cattle, dogs, and humans and as soon as one comes along they attach to the body and start feeding. It is estimated that the adult females increase in size to around 11 mm when fully engorged. Mating takes place either on or off the host prior to the female engorging, once mated the male dies and the female then spends between 6 and 13 days feeding after which it drops off the host and lays her eggs thus allowing the life cycle to begin again. The length of the tick’s life cycle can vary depending on climate conditions, but normally on Dartmoor lasts about three years, a year for each stage. Ticks are normally active between the months of May and November.

Some, note some, ticks can carry Borrelia burgdorferi which is better known as Lyme’s disease and can be passed onto their hosts – namely us. It is thought that Lyme’s disease has been present in the UK since the 19th century so by no means is it a new phenomena. Its symptoms are flu-like feelings, tiredness, aching muscles, and a rash. If not treated these can develop into more serious conditions such as nerve or heart disease and rheumatism. The disease is carried in the tick’s gut and saliva so it is not always the case that the tick has to engorge to transmit the infection, the saliva itself can cause the problem. In the November of 2019 it was announced that in a study carried out by the University of Glasgow another form of tick-borne disease has reached the UK. The organism named B. venatorum causes babesiosis, an animal disease recognised as an emerging infection in people. Previously this was extensively confined to China and Europe but has now made its way into Scotland. Scientists collected blood from sheep, cattle, and deer in the north-east of Scotland where tick-borne diseases have previously been detected. DNA from the parasite was detected in the blood of a large number of sheep, which were not showing any sign of disease thus making them carriers. A university clinician commented that; “The presence of B. venatorum in the UK represents a new risk to humans working, living, or hiking in areas with infected ticks and livestock, particularly sheep. Although we believe the threat to humans to be low, nevertheless local health and veterinary professionals will need to be aware of the disease if the health risk from tick-borne disease in the UK is to be fully understood.” It is thought that migratory birds coming from Scandinavia were responsible form transmitting the disease to the UK. Please note – as yet there is no evidence yet of B. venatorum spreading to Dartmoor but I’m sure it’s only a matter of time.

Below is the consensus of advice for avoiding contact with sheep ticks

1. Wear long trousers with the legs tucked into the socks.

2. Wear long-sleeved shirts to cover the arms.

3. Wear white coloured clothing where possible, this will allow you to spot the ticks easier.

4. Always carry out frequent body inspections, especially after returning home.

5. It has been shown that ticks can lay their eggs in the house, regular vacuuming helps.

6. Both human and dog insect repellents can reduce the risks.

7. Remove and ticks as soon as possible.

8. Where possible avoid areas of dense vegetation, especially where stocked with sheep.

9. Avoid trees and rock shelters often used by sheep.

What is the best way to remove a tick? There are many ‘traditional’ methods such as placing a cigarette on the tick, applying liquids and oils to suffocate the tick, none of these are 100% effective. The only way to remove an embedded tick is to grasp the head with tweezers as closely to the skin as possible. Then with gently applied pressure draw the tweezers back in an anticlockwise upward direction, having removed the tick wipe the bite area with an antiseptic. It is now possible to buy specially designed tick tweezers for use in pets and humans. Official recommendation is that if you have been bitten by a tick and it has been removed, the next step is to consult your doctor, some even suggest keeping the dead tick in case it needs to be examined for Lyme’s disease. Remember dogs also pick up ticks so regular inspection and removal where necessary is equally as important. For more information on ticks and Lyme’s disease visit the Lyme Disease UK website – HERE.

With regards to Dartmoor obviously there are numerous sheep and increasingly areas of dense bracken (due to the reduced stocking rates on the moor)both of which are associated with ticks. Farmers realise the problem and will regularly treat their livestock with applications designed to control ticks. In the case of sheep, especially those grazing moorland, the best treatment have always been dips. Up until this year there have been two types, OP’s or organo phoshpates which contain diazinon and Non-Op’s or cypermethrin based dips. Diazinon will give 6 weeks protection against ticks and cypermethrin will provide 8 weeks cover. So clearly where farmers are using such products their livestock are not adding to the tick burden. OP’s have had a bad press over the past 10 years or so and some farmers will not use them and so use the alternative cypermethrin products which come in a pour-on presentation. Other chemicals also available as pour-ons are deltamethrin and alphacypermethrin. This now means that the only option the farmer has of controlling ticks by the dipping method is to use OP’s. As mentioned a few don’t want to use such preparations and so there is the possibility that their sheep will not be treated for ticks. This will result in the animals health suffering and the rise in the uncontrolled tick population. On some of the Welsh mountains if sheep, especially lambs, are not treated with tick controls they will be dead within a day, such is the extent of the tick infestation. It is also worth noting that deer can also be hosts to the sheep tick and their numbers seem to be increasing on the Moor.

But please don’t get the impression that Dartmoor is infested with life threatening ticks, yes they are present but with sensible precautions the risk of infection is minimal. By no means is this problem exclusive to Dartmoor, the problem is becoming a countrywide concern that is not just restricted to upland, moors and heaths.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor