The Dartmoor Tinners have always been a law unto themselves, at one time they had their own parliament and laws with the rights to virtually mine tin wherever they wanted. Recent legend tells of how they even had their own symbol or badge in the shape of three rabbits running in a circle.

Careful research has revealed that this is untrue and in fact the symbol has much older roots. In her book ‘The Outline of Dartmoor’s Story’, Lady Sayer wrote(p.24):

“The Fifteenth century was a particularly prosperous time for Dartmoor tinners, and by way of a thank-offering they enlarged and rebuilt some of the moorland churches. Widecombe church is a fine example, and there you can see the tinners’ emblem carved on a roof-boss – three rabbits sharing ears…”

This was probably the first serious mention that linked the symbol with the tinners. The connection between the symbol and the tinners may have arisen because the ‘Three Rabbits’ can be found in some of the Dartmoor churches which would have been in mining areas. If one accepts that the actual symbol shows hares and not rabbits then there is a deep hidden history to be found.

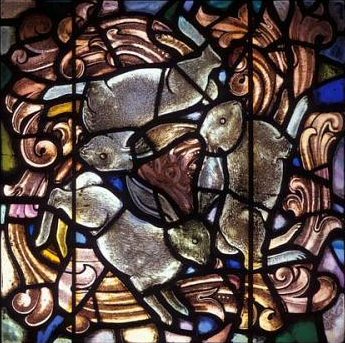

Ok, let’s look at where the three hares can be found, most of the old examples are in churches, in Devon there are 28 in total of which 19 are of a possible medieval origin and of these 12 are on or very near Dartmoor. All are carved wooden bosses and are located in the roof. There are 2 examples which appear on plaster ceilings of private houses and a modern example of a stained glass window which is located in the door of the tinners bar at the Castle Inn in Lydford.

Looking further a field there are instances of church bosses to be found in Corfe Mullen, Cotehele, Selby Abbey, St. David’s cathedral and Llawhaden. In Long Melford church the design can be seen in a medieval stained glass window and in Chester cathedral it appears in a floor tile. Scarborough can boast having the design set into a plaster ceiling. Although this is not a long list the distribution is far and wide. When looking in a global context, there are examples to be found in France, Germany and Switzerland, Southern Russia, Iran, Nepal and China. The earliest known example is the Chinese one which dates to around AD600. The Nepalese examples have been dated to around AD1200 and the Afghanistan instance to AD1100. The earliest European examples date to around AD1200 with the English ones at around AD1300.

What does the actual symbol look like? It actually depicts three rabbits running in a circular formation. Bit like a ‘harey merry-go-round’. Their ears interlock in the centre – and here is the really clever bit, they actually form an optical illusion in that although they all appear to have two ears in fact only three are actually depicted.

The Three Hares Symbol

Having established what the symbol looks like, the main question to answer is why the hare and what did it represent? In their book ‘The Leaping Hare’, George Ewart Evans and David Thomson (1972pp. 15-17) point out that in early Chinese mythology the hare was a symbol for resurrection. In fact the Chinese don’t refer to ‘the man in the moon’, they refer to ‘the hare in the moon’. This hare in the moon is said to pound the herb of immortality. In India there is a similar legend and in addition the hare figured as a sacrificial animal that offered itself to be burnt in order to provide food for Brahman. In ancient Egypt the figure of a hare was used as a hieroglyph which denoted existence. In Europe there is evidence of a cult of a hare goddess. In his book ‘The Sacred Ring’, Michael Howard explains that in Saxon times the Goddess Oestara or Eostre was said to rule over the spring and the dawn. Her sacred animal was the hare which was also the symbol of the moon. Coincidentally, the gestation period of a hare is 28 days which is comparable with the moons monthly cycle. And whilst talking cycles it is also interesting to note that the female monthly cycle is affected by the hormone oestrogen and also lasts about 28 days. Howard goes on to note that the moon hare was supposed to have laid the Cosmic Egg from which emerged all life. (1995 pp. 58-9). It is from Eostre that we get the festival of Easter which originally celebrated the coming of spring. It was only when the Christians came along that the festival was bastardised to represent their celebration thus overshadowing the origin pagan concepts. The very symbols of the pagan festival were transformed into Christian icons, the ‘hare of Eostre’ became the ‘Easter Bunny’ and the ‘Cosmic Egg’ became the Easter egg. In pagan time special cakes were baked as sacrificial offerings to the moon goddess and were marked with an equal-armed cross to divide the cake into four quarters. These represented the four lunar quarters. The cake was then broken up into pieces and buried at the nearest crossroads as an offering. Yet again this has been plagiarised into the cake becoming the ‘hot cross bun’ and the cross representing the cross of Christ. Believe me, the more you study folklore, myth and custom the more you realise that the early Christians didn’t have an original idea amongst themselves. They simply converted any pagan site, custom or belief into one of the Christian doctrines – this is another subject so had better way leave it there. Ralph Whitlock, in his book ‘In search of lost gods’, suggests that the hare was an early Celtic form of divination and that when Queen Boudicca was assembling her army prior to kicking the proverbial out of the Romans, a hare shot out from under her cloak and fled in panic, this was a portent meaning the Romans would be put to flight (1979 p.74) It is also interesting to note that once the hare symbol had been Christianised into a fluffy Easter bunny that same religion soon associated the hare with evil. The other association transferred from the hare to the rabbit was the tradition that its foot was a good luck charm. In his book ‘Folklore, myths and customs of Britain’, Marc Alexander gives several examples of how the hare was regarded in legend. For instance, if you dreamt of a hare you were being warned of an imminent death in the family. If a pregnant woman saw a hare then the baby would be born with a ‘hare lip’. It was also said that if a hare crossed the path of a wedding procession then the marriage was doomed (2002 p.124). In Cornwall it is said that girls who died of grief caused by a fickle lover turned into pure white hares and haunted the guilty parties. It is the connection with witches that has earned the hare its worst association with evil. Tradition holds that witches could turn themselves into hares as in the story of Bowerman’s Nose. Alexander gives an example of how in 1662 a woman named Isobel Gowdie was put on trial for a charge of witchcraft. She related how she and other witches could transform themselves into hares by repeating: “I shall go intill a hare, with sorrow and such meikle care and I shall go in the Devil’s name at while I come home again“. Any Dartmoor enthusiast will be aware of the legend of the witch from near Buckland who would send her grandson to direct the local squire’s hunt to where he knew a hare would be. This story can be found in local lore all across the country. One variant is that the huntsman shot the hare with a silver bullet and then found the old woman with a bullet wound. The silver bullet was meant to be the only thing that could harm a witch. Bit like the werewolf legend. Well ok, that was a rambling way to ascertain that the hare clearly was a mystic symbol with roots deep into pre-Christian times. Worldwide it represented the moon and in general life and rebirth and of course the female figure. But as far as the tinners of Dartmoor are concerned I think it is just a co-incidence that many of their churches depict this symbol and that it was clearly a ‘in thing’ as far as church decorations go.

Three Hares window – Castle Inn, Lydford – Chris Chapman.

There is an excellent website on the Three Hares Project which depicts many of the three hares symbols on church bosses.

Bibliography.

Alexander, A. 2002 Folklore, Myths & Customs of Britain, Sutton Pub., Bath

Ewart Evans, G. & Thompson, D. 1972 The Leaping Hare, Readers Union, Trowbridge.

Greeves, T. 1991 Tinners Rabbits, Dartmoor Magazine No.25, Quay Pub.

Greeves, T. 2000 The Three Hares, Dartmoor Magazine, No.61, Quay Pub.

Howard, M. 1995 The Sacred Ring, Capall Bann Pub., Chieveley.

Sayer, S. 1987 The Outline of Dartmoor’s Story, Devon Books, Exeter.

Whitlock, R. 1979 In Search of Lost Gods, Phaidon Press, Oxford.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

I think the symbol emphasises the ears so in mythology the asses ears of Midas comes to mind –

No one seems to be able to solve the mystery of Hares being on the roofs of many churches? It must mean something but what? They are glorious creatures and need to be protected. when l had my family ‘Coat of Arms” researched, names of animals were often used as “nicknames” for the knights in the field of battle during the crusades ie:- fleet of foot, and originated from Norman ancestry, and of course the colours were to be able to identify each knight during battle. Very interesting are the Hares in churches connected to the Normans or is it linked to Anglo-Saxon?

Hare myths come from Asia so going with that you will notice the hare is opposite the rooster in the Chinese Zodiac. The Ostara myth linking eggs to hares for Easter says that a hare transformed or took the place of a bird? Complex if you ignore history links, simple if you have looked at the Chinese zodiac and can fathom sharing between cultures. So obviously hares went on roofs just as roosters go on roofs today because they represent characters opposite one another in a zodiac. They represent spring and fall, night and day. The rooster is associated with morning yet represents fall, the hare is associated with night yet represents spring. They act like a yin and yang. Three hares most likely stands for the three months or moons in the spring season. Just like I found the puzzle of six blind men touching an elephant describing different aspects that shape another thing easily explained when looking at the endless knot. Which is six, sixes that together form a seventh object. This is also possibly where the rooster lays an egg puzzle comes from. A fall egg equals a fruitless lay?