The Merrivale ceremonial complex is probably one of the second most important ritual landscapes on Dartmoor. The inquiring mind will find many references to it in many books. But they are all brief mentions, which leaves the reader thirsting for more knowledge. This is an attempt to bring all those snippets together and to provide a larger picture that encompasses not only single features but the whole ritual landscape as a complete entity.

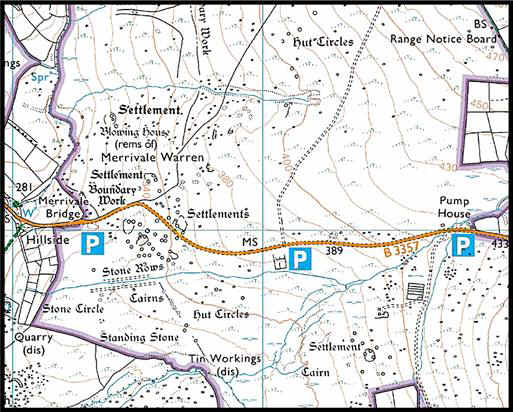

As with any investigation into a landscape it is helpful to start by looking at a map. This will present a picture of the surrounding landscape and its features. The Ordnance Survey map for the Merrivale area is shown below.

As can be seen from the map, the area shows features from various historical periods. Clearly there are the pre-historic remains; there are later features such as the warren, the blowing house and tin workings associated with mining activities. There are modern features such as the pump house and quarry. All these features have been built up layer upon existing layer through the ages. These various combined layers of activity are known as a ‘palimpsest’. This has made the landscape into a sort of layer cake and to discover the prehistoric layer we must metaphorically strip away all the previous features, leaving us with the early landscape with its features and uses. This examination will only be concerned with that early prehistoric layer and feature on the ritual remains of the complex, namely the stone rows, circles, cairns, menhir and kistvaen.

Having looked at the map, it is then useful to see if there are any clues in the actual place name. The first recorded mention of Merrivale was in the assize roll of 1307 when it was recorded as Miryfield. Glover, Mawer and Stenton (1992 p.247) suggest that the meaning of Merrivale is ‘Pleasant open space’ derived from myrig (pleasant) and feld (open space). Over the centuries this has now mutated to Merrivale. There is nothing to be gleaned from this place name, except a question, why was this open space ‘pleasant’? Was it pleasant in a scenic way or was it pleasant in a spiritual way? If the latter, then could this indicate that this area of land had an ancient ‘spiritual’ meaning of some sort?

The Merrivale ceremonial centre is located on a spur of high ground above the river Walkham. Merrivale contains four elements of a prodigious ceremonial centre: stone rows, stone circles, standing stone (menhir) and burial cairns. Although present fields have been established within 200m of the west end of the rows and a newtake wall built near to the standing stone, it appears that no part of the site has been destroyed on this side. Sadly the same cannot be said for the rest of the complex. Plans of varying reliability were made in the nineteenth century and from these it seems that two large cairns and a ring cairn have been totally lost, the Merrivale cist or kistvaen has been wrecked and many of the surviving cairns have been plundered, probably centuries ago. Rowe (1985 p.208), notes that in the 1860s a man called Harding cut two gateposts out of the capstone. In the early nineteenth century, Miss Sophia Dixon of Princetown described the excavation of one of the cairns in a letter to here friend Miss Evans. She noted: “On digging into one of them we procured a substance singularly interesting, as it was believed … to closely resemble … the remains of human, or at least animal ashes”. Samuel Rowe also describes the excavation of a cairn at Merrivale. He first visited the site in 1827 with Colonel Hamilton Smith where he recalls:

“No sooner did we mount the slope, than the Colonel instantly detected this interesting and characteristic feature of aboriginal worship, and pronounce the rows of stones to be nothing less than avenues, constructed for the purpose of solemn Arkite ceremonial.”

It is worth remembering that there was a vogue during the early 1800s for attributing nearly every archaeological feature or strange rock formation to the Druids and their ritual practices or to other strange biblical races. In this case, Arkite is defined as: “a designation of certain descendants from the Phoenicians or Sidonians, the inhabitants of Arka, 12 miles north of Tripoli, opposite the northern extremity of Lebanon. There are various theories that the Phoenicians visited Dartmoor in search of tin. Clearly back in the late 1800s archaeology was in its infancy and had many fanciful theories and practices. Around the same time various travelling writers were wandering the wastes of Dartmoor postulating about what they discovered.

One of the first descriptions can be found in Mrs Bray’s book, ‘Borders of the Tamar and the Tavy,’ published in 1836, she describes Merrivale in the following manner:

“We have on Dartmoor, at a short distance from Merrivale Bridge, and nearly four miles from Wistman’s Wood, some very remarkable vestiges of the cursus, or via sacra, used for processions, chariot races, etc., in the Druidical ceremonies. This cursus is about 36 paces in breadth, and 217 in length. It is formed of pieces of granite that stand one, two, or sometimes three feet above the ground in which they are imbedded: a double line of them appears placed with great regularity on either side, as you will see in the drawing of the ground-plan. A circle in the middle of the cursus breaks the uniformity of line in part of it. There are, near this extensive range of stones, many remains of Druidical antiquity; such as a fallen cromlech, a barrow, an obelisk, a large circle, and several foundations of the round huts or houses of the Britons.”

John Lloyd Warden Page describes what he found at Merrivale in 1895 (pp134-138):

“These interesting antiquities will be found close to, and for the most part on, the south side of the road, which passes through what appears to have been part of an aboriginal village. Close to these hut-dwellings are two avenues, running nearly due east and west, the one 780 feet in length, the other 590. The stones are about 2 feet apart and of most irregular height, though seldom exceeding 3 feet. They vary much too, in shape; evidently no tool has been used upon them, so that some are thin and pointed and others thick and truncated. A circle with a diameter of 11 feet 8 inches, and which appears to have contained a kistvaen, stands about the centre of the larger avenue. Proceeding down this avenue from the east end, we shall, after travelling some 250 feet, find at a distance of less than 100 feet to the south, the remains of a cromlech. The cover stone, of which the centre part has evidently been removed by some granite-robber, is 6 feet 7 inches by 5 feet 1 inch, and 15 inches in thickness. Towards the west end, at a distance of 26 and 72 feet respectively, are the ruins of two small cairns. We now steer for the tall menhirs still further to the south. On the way we pass an almost perfect sacred circle consisting of ten low stones, the largest being about 1 foot 10 inches high by 2 feet wide. Its diameter is 54 feet. From this the menhir is distant 105 feet. It is a remarkably fine specimen, and the tallest on the moor, having a height of about 13 feet. Surrounding it is an imperfect circle of small round stones about 6 inches high. The hut circles and supposed pound to the north of the avenues call for no especial attention.”

He also includes in his book an illustration of the “stone avenues”, sadly the drawing is not attributed to any artist but as can be seen from the picture below there was a certain amount of ‘artistic license’ used.

Page also describes some of the farming practices at the time as being responsible for some damage. He remarks: “Turf-cutting in the immediate vicinity of the longer avenue is probably responsible for the demolition of the circle, while the tempting shape of the slabs in the cairn proved too much for the archaeological tendencies (if he had any) of the moor farmer”. Finally he ends his ‘virtual tour’ of the complex by putting forward some theories of the time regarding the original purpose of the features. One possibility was that they are “relics of ancient British serpent worship”. Another idea was that “the avenues were erected in memory of some great battle and represent the lines of opposing forces, or perhaps the ranks defending the village in the rear”. He then suggests that perhaps the space between the avenues was “a racecourse for British charioteers, or a processional path of the Druids” with the cromlech being used as a “place of sacrifice”.

One could nearly suggest that as Mrs Bray’s book was published sixty-nine years before Pages’, a certain amount of plagiarism took place. Today we can sneer at these early ideas and theories. Heaven help us, we all know that the Druids were a feature of the Iron Age and the earliest chariot so far discovered is at Wetwang and dates to 400BC. Both postdating the Merrivale features by at least a thousand years and oh aren’t we so clever. What about some of the modern theories? “They are landing strips for alien space crafts” or they are “centres for earth energies.” Surely, we have no excuse for such thoughts over a hundred years on. Either way, it is useful to examine the early writings of Merrivale and compare them with the modern thinking.

The next respected author to comment on the complex was the famous William Crossing. In his book ‘Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor’ (1990 pp.94-5) he suggests that having passed up the Princetown road one should strike off across the common to the menhirs near the Long Ash Enclosures. Firstly one will find the stone rows described thus:

“There are two rows, both being double, and some faint indications of a third nearer the menhirs. The direction of the two former is nearly due east and west, and they are roughly parallel to each other… The length of the southern row is 850 feet and that of the northern 590. About the middle of the former is a stone circle and at the eastern end of the latter a large stone. Near the north-western end of the southern row is a small cairn, much dilapidated, and about 600 feet south-east of this, and also near the same stone row, is a ruined kistvaen. This was formerly regarded as a dolmen or cromlech, and is marked as such on a plate illustrating a paper by the Rev. Samuel Rowe… Unfortunately the cover stone is broken and one of the side stones also. This damage was done about the year 1860; gate posts being cut from the former and part of the latter being removed. A few years ago an examination was made of the kist, and a flint scraper, flake and polishing stone were found.”

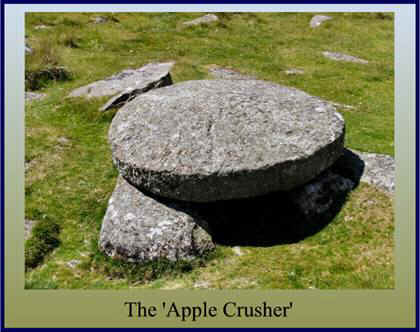

He then goes on to describe the settlement, which lies to the north of the stone rows. One interesting observation he makes is regarding the ‘apple crusher’ or millstone that is in-situ within the pound. He notes that:

“Visitors are cautioned not to allow their antiquarian zeal to carry them as far as to suppose this to be a dolmen. It is true that a well-known archaeologist once made this mistake, but with the history of the stone before us there can be no danger of our doing so. He afterwards discovered that what he had regarded as an ancient monument had been fashioned by a man then living in the vicinity. The piece of granite had been intended for a millstone, but was found to be unfitted for the purpose.”

Crossing elaborates on this matter further in his ‘Dartmoor Worker’ (1992 p.113) by naming the archaeologist as being Mr C. Spence Bate. Having discovered the cromlech he enlisted the help of another antiquarian who confirmed his theory. It was a few days later when Spence Bates’ son visited the site and on his return home informed his father that he had “found out all about that stone for you. I know the name of the man who cut it”. Here Crossing suggests that the stone had been cut for pounding apples

Crossing’s final thoughts on Merrivale are that the stones in the rows and circles are small, and the final effect cannot be said to be striking, which could be taken to mean he was not at all impressed, which could be anybody’s initial thoughts until the whole complex is taken into consideration.

Pettit (1974 pp.156-8) considers that the Merrivale complex has attracted much attention since 1802 when the first attempt was made to describe it. Many conflicting and inadequate reports have been made, each suggesting some former feature that is no longer visible. He comments on several pits that were found close to the stone circle. Each one was between 12 and 18 inches deep and one of them contained a flint flake. In Pettit’s opinion these were either sockets for stones, pits for burials or pits for ritual deposition. The age of ‘ritual’ has dawned. It is interesting to note that in all the previous descriptions and theories about Merrivale the word ‘ritual’ has not appeared once. It is from the 1970s onwards that this enigmatic term occurs in archaeological contexts. What does it mean? Basically everything and nothing and is an excellent terminology for “not really sure”. One observation Petit makes is that what survives today are but vestiges of a great Beaker monument, the complete plan of which is most likely lost for ever. As far as the features go, Pettit describes them thus:

“The two main rows run east and west some thirty yards apart and, diverging by only 2.5º look parallel. There is no other example on Dartmoor of rows forming an avenue like this. A leat, constructed between them during the nineteenth century, is no longer maintained and the water artificially brought to the site overflows and creates a morass… The northern row is 180 yards in length; a double stone row with some 160 stones remaining, many of them very small. Fifty-five pairs indicate that the space between the lines varied in the usual way. The course of the row is irregular. A substantial transverse slab marks the slightly higher end, but at the lower end there is nothing, no stone or cairn or trace of a cairn. The southern row is 100 yards longer, projecting beyond the northern row at both ends. Over 200 stones can be counted though many are very small. Seventy-five pairs show, as in the other row, a varying though smaller space between the lines. It also has a transverse stone at the higher end, a fine triangular slab, and nothing at the lower end. However, two largish stones of similar shapes, a pillar and a broad slab, form the last pair at the lower end and may indicate the former presence of a cairn. The unique feature of this stone row is a cairn of 12ft diameter, marked by a circle of stones and with traces of a kist, roughly midway along it. No other row on Dartmoor is interrupted in this way. The third row at Merrivale is single and short – a mere seven stones and a terminal stone marking a distance of 40 yards. It leads to a very small cairn sited a few yards from the southern double row. The alignment diverges more than 50º from that of the double stone row. Within a short distance of the southern stone row is another ruined cairn and also a large kist. A little further south lies a stone circle … The eleven remaining stones are small and appear to be short pillars alternating with broad stones with flat tops. Close to the circle is a fine standing stone, 10.5 feet above the ground. South-eats of this lies a ruined cairn and beyond this, and in the same line, a smaller single stone. This was re-erected in 1895 and has since fallen again. It is doubtful whether it was ever a true monolith: more likely a substantial stone in a row or cairn circle. A few set stones scattered about the ground here and close to the standing stone may be the relics of rows or cairn circles. Much has obviously been destroyed. But with the abandoned leat running through the double rows and the main road only a few hundred yards away, perhaps it is remarkable that so much of Merrivale remains.“

There are several interesting remarks in the above description. Twice it is noted that some of the features of the Merrivale monuments are unique to Dartmoor. These being the central cairn of the southern stone row and the actual avenues formed by the stone rows. Does this suggest that Merrivale is ‘special’ in some way? He also remarks how the leaking leat has made the site a “morass”, luckily the leat has been repaired and today there is very little evidence of morasses caused by an unmaintained leat.

Another noted author to remark on the Merrivale complex was Eric Hemery. In his book ‘High Dartmoor’ (1983 pp.1046-9) he describes the site as: “consisting of kistvaens, a stone circle, menhirs, cairns, three stone rows, each with a blocking stone – two double and one single, as well as traces of at least one other single stone row. Hemery records the northern stone row as being 180 yards long and the southern row 280 yards long.” And apart from a brief description of the cairns, kistvaen and stone circle, is all he has to say.

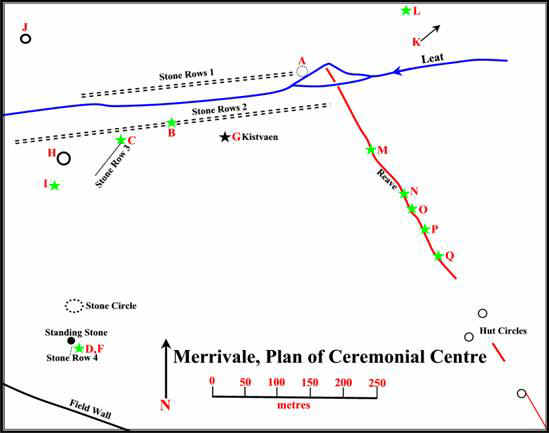

Visit the Merrivale complex today and what do we see? Basically about the same as Page saw in 1895. Probably the most accurate and detailed description of the site is that given by Jeremy Butler (1994 pp. 24-31). He recommends that the best approach to the monuments is downhill from the east; this is the only direction that delivers a view over the whole complex. A plan of the features is shown below in figure 3.

The first features to draw the eye are the two double stone rows. These are aligned along the crest of the ridge shown as stone rows 1 and 2 on the plan. They are not quite parallel with each other and consist of neatly paired stones. Neither row is exactly straight.

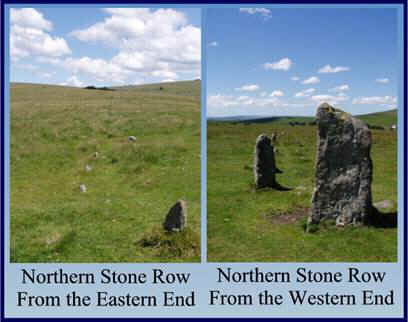

The northern double row is the shorter of the two and measures 183m. It is also more regular with a more constant orientation that varies less than a degree between both ends. The distance between the two rows narrows slightly from 1.3 to 1.2m at the eastern end. The intervals between the stones gradually increase from 1.6 to 1.9m in the same direction. At the western end a large slabs marks its terminal, originally there was a blocking stone 2.8m long set between the stones. This stone had already fallen down when Mrs Bray visited in 1802. Since then it has completely disappeared so that even the socket hole is no longer visible. A cross slab is also set across the uphill end of the rows; this is the last surviving member of a cairn circle which once terminated the stone row (marked A on plan). We know the cairn circle existed as it is marked on an early plan of 1879. The northern stone row can be seen in figure 4 below:

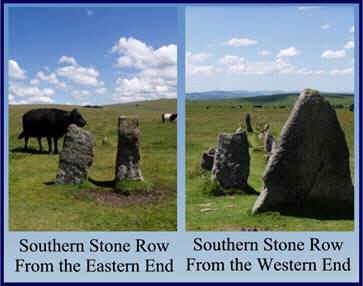

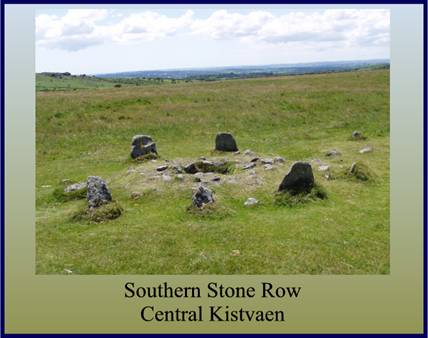

The southern double stone row (marked Stone Rows 2 on the plan) is 263m long. A triangular shaped blocking stone stands between these rows at the eastern end. A small cairn interrupts the rows midway along (marked B on plan) the rows. This cairn virtually separates the rows into equal halves. There are five remaining stones from the ring of the cairn and two sides of a central kistvaen. The Reverend Bray excavated this in 1802 but found nothing. The southern stone row is shown in figure 5 and the central cairn and kistvaen in figure 6:

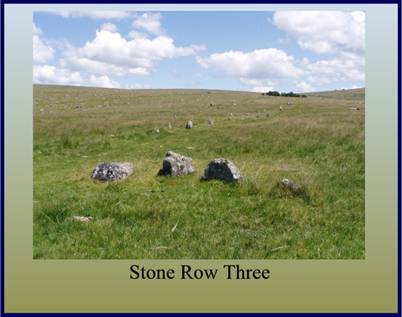

A much shorter single stone row lies to the south (marked Stone Row 3 on Plan) it has a slightly curving alignment and runs down a shallow incline. At its northern end is a cairn (marked C on plan). There is evidence that at some stage this cairn has been excavated as the vestiges of a trench can be seen running from the southern end into the centre. Stone row three is shown in figure 7 below:

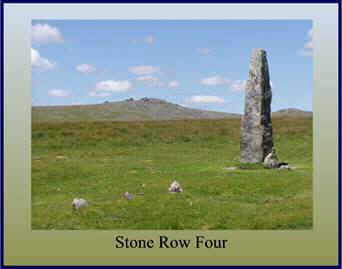

Stone row four is now a very small affair that consists of only 3 small slabs that are aligned towards a squarish slab by the base of the menhir. It is noted that in 1895 there were 5 stones, the pit that has now appeared between the upper stones probably accounts for the missing one. This may well have been the site of the cairn, which was at the head of the rows and was recorded by Rowe and is marked ‘D’ on the plan. The row is shown in figure 8 below:

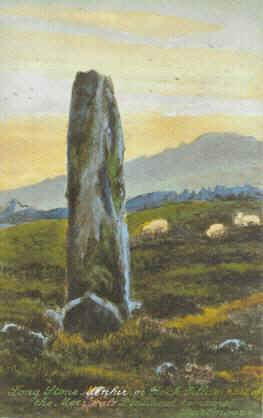

The menhir stands at 3.1m and is still in its original position, that being 42m due south from the centre of the stone circle. There is a 2m long pillar lying a short distance from the menhir. Although this was erected in the pit near to the menhir in 1895 there is no evidence that it ever stood upright. The menhir is shown in figure 9 below:

Between these stones the pit of the cairn marked ‘F’ on the plan can be seen.

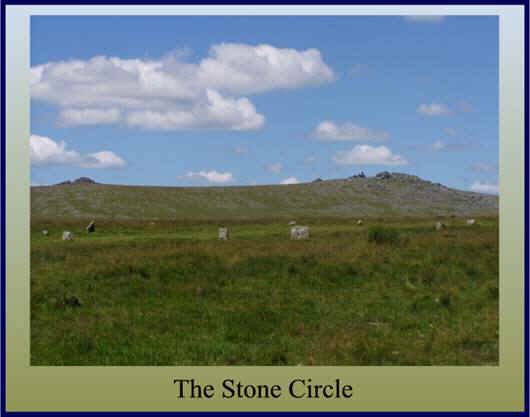

On the south-facing slope the stone circle occupies a less prominent position than the double stone rows along the ridge. It consists of 11 stones averaging 0.4m in height. Their arrangement is eccentric to say the least, with most of the stones being up to a metre off a true circle 19m across and with very variable intervals between. The strange thing with the circle is that several detailed accounts of the nineteenth century show that the number of stones has varied from 9 in the early part of the century, 8 in 1828, 10 in 1829, 9 in 1859 and finally 11 in 1895. This means at least 2 stones have been added, probably by some of the early antiquarian investigators who were not always accurate in recording their restorations. The stone circle can be seen in figure10 below.

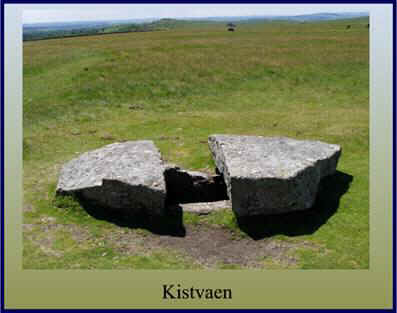

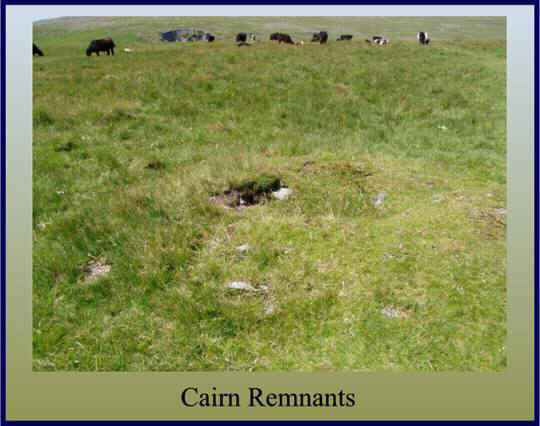

The cairns are clustered around the rows and whatever ritual concepts they followed meant the site developed into something of a necropolis. Apart from the cairns directly associated with the stone rows the remnants of another 13 can be found in the vicinity or are know to have been lost in recent times. The cairn that once covered the Kistvaen (marked G on the plan) is estimated to have been 2.2m long, making it one of the largest on the moor. The kistvaen was already exposed and intact when Mrs Bray visited it in 1802. But by 1870 the slab, has already been mentioned, was damaged. The kistvaen is shown in figure11 below:

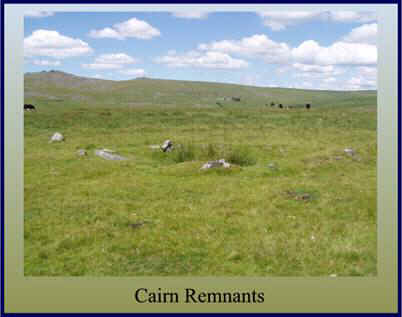

Another cairn once existed towards the western end of the southern stone row (marked H on the plan). This would have measured about 20m across; sadly the stones were removed and used for road repairs just after 1851. The cairn is illustrated in figure 12 below:

Another smaller cairn measuring a mere 3.6 metres across can be found to the south of cairn ‘H’ and is marked ‘I’ on the plan. This is illustrated in figure13 below:

Almost in line but north of the double stone rows is a circle of slabs. This is recorded as a ‘hut circle’ on the Ordnance Survey maps. However it is possible that as there is a single ring surrounding a flat interior, this could be the site of another cairn. This feature is marked ‘J’ on the plan. There is early evidence of a large cairn once situated on the north side of the present road and is marked ‘K’ on the plan. It was shown on a map drawn up by the Exploration Committee’s report of 1895 and appears to have been roughly the same size as the large cairn once covering the Kistvaen (‘G’ on the plan). The other main cairns (marked M, N, O, P and Q on the plan) are all sited alongside or across the reave which runs northwards from the Long Ash enclosures. Because some of the cairns are built across the reave and have left gaps in it where the stones were taken for the building materials, it can be assumed that the reave pre-dates the cairns. Two more cairns are located above the leat and are marked ‘L’ and ‘K’ on the plan.

Having mentioned about how modern man has desecrated various features at Merrivale it is interesting to note how considerate the leat builders were. As can be seen in figure 14 below, they built the leat straight between the two sets of stone rows. Although the leat caused later damage due to the lack of repair its original construction appears to have had little structural effect on the site.

Previous attention has been given to the mysterious ‘dolmen’ cum ‘apple crusher’ that can be found in the remnants of the pound to the north of the stone rows. Miraculously this still survives today, although in light of the modern day plundering of granite artefacts, it is questionable how much longer it will remain. This feature is shown below in figure 15:

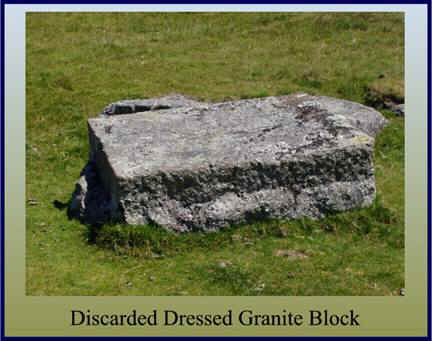

There has been previous mention as to how modern man has been exploiting the site with regards to stone removal. A visit to Merrivale will soon reveal the extent of how the stonecutters worked the area. Figure 16 below shows just one of many examples of blocks of granite that have been worked in-situ and for some reason or other discarded. If the number of remaining slabs of worked granite are regarded as waste, what else has been deemed complete and removed?

One would have thought that given the age of the Merrivale stones and the superstitions of the old moor folk that myths and legends would abound. Sadly this is not the case. Crossing (1990 p. 94fn) notes how the stone rows were formerly known locally as the ‘Potato Market’ and ‘The Plague Market’ and that a tradition stated that food and provisions were brought to the stone rows by the country people and left as supplies for the Tavistock towns folk at a time when the plague struck the town.

Crossing’s source of information may have come from Mrs Bray as she remarks:

“They are stated by tradition to be the enclosures in which, during the plague at Tavistock, (that they might have no intercourse with its inhabitants) the country-people deposited the necessary supply of provisions, for which within the same the townspeople left their money. That these circles may have been applied to this purpose is not improbable; particularly as the spot is still known (and indeed is so distinguished in some maps) by the name of the ‘Potato Market.”

In view of the existence of the splendid Kistvaen, again there is no legend attached to it. Many of the other kistvaens on Dartmoor have stories of hoards of treasure and curses such as ‘The Money Box’ and ‘The Crock of Gold’, but ‘nought’ for Merrivale.

Having looked at the archaeological remains of the complex, what can we surmise was its purpose? It will be interesting to look at several viewpoints, firstly the modern archaeological theory, then the more fanciful yet none the less plausible archaeological idea and finally delve into the realms of myth and magic. Depending on where ones sympathies lie all are possibly valid explanations. If anyone can positively prove to what purpose this complex was used then they could become very rich and very famous.

From a modern archaeological aspect the purpose of the Merrivale complex can easily be described as ‘ritual’. Gerrard explains this concept most succinctly in his book, ‘Dartmoor (1997 pp.54-64). Firstly it will be as well to put a date to the various monuments to be found at Merrivale; here we are talking the Bronze Age (c.2300-700 BC). So what was happening at this time? The place to get that answer is the landscape. From looking at today’s landscape we can see that during the Bronze Age there were cultural and social changes occurring. Whilst the stone rows and circles from the Neolithic period were still being used, cairns continued to be used for housing the dead, but now instead of containing multiple burials they contained individuals. We also see the appearance of stone-built settlements and their associated fields. By the Middle Bronze Age (c.1400-100 BC) there is evidence of several large and well-defined ‘territories’ marked out by a series of boundary banks called reaves (more of which later).

The Merrivale complex demonstrates every example of Bronze Age monument, namely burial cairns, a menhir, a stone circle and stone rows. These ceremonial monuments were built by people living in the nearby settlement and must have played an important part in their lives. The location of ritual monuments may also reveal how the landscape was organised to meet what spiritual requirements the early moor dwellers had. It has been suggested that ‘prestige cairns’ (cairns with a diameter of more than 20 metres) lie in impressive locations that would enable them to be seen from great distances. One reason for this could be that they were meant to impress and inform neighbouring groups or newcomers that the area was already occupied – a ‘trespassers will be prosecuted’ sign. They may also have been seen as a symbol of social identity and ‘oneness’ to the communities that built them. Smaller cairns possibly were used to delimit territories at a local level. It has also been suggested that the occurrence of clusters of cairns around stone rows may also have been used to delineate territories and also that clusters indicate a settled population which used the same site for several generations. It is generally accepted that the presence of five or more cairns places the site into a category defined as a ‘cairn cemetery’. Where does this place Merrivale? It has been established that the cairn cluster around the reave consists of five cairns, therefore this can be regarded as a ‘cairn cemetery’. The cairns are also associated with the stone rows so maybe they were used to mark out a local territory and also their numbers suggest a settled population. There is possible evidence of 2 cairns that had a diameter of over 20 metres thus giving us at least two ‘prestige cairns’. Were these used as symbols of power and status for the inhabitants of the territory that they marked? It is interesting to note that the cairn cluster post-dated the reave. As noted above, reaves were originally used to delineate territories, so did cairn building imply that the political statement made by the reaves was no longer strong enough? Therefore, necessitating the need for stronger markers.

Considering the size of Dartmoor and the number of pre-historic features existing within its boundaries there are very few examples of standing stones or menhirs. They are typically very difficult to date, however some examples in the south west are known to be associated with Bronze Age material. The general consensus is that the Merrivale menhir is Bronze Age in date. The menhir is one of the most puzzling archaeological features as there are several ideas as to its original purpose. Was it a way marker, a territorial marker, a grave, a cemetery marker, a focus for ritual activity or did it denote a meeting place? The Merrivale menhir could easily be one or a combination of the above suggestions. Personally I would disregard the territory marker theory as there is evidence of a reave which clearly denotes a territory along with the many cairns. Is it plausible that the stone marked a track way? Possibly, but its location would have been better served higher up the slope if this was the case. Could it be a grave? Maybe, but if all the features date to roughly the same period why would they use a menhir to mark a grave when they are already building cairns (and big ones at that) to serve the same purpose. Considering how near the stone is to the cairn cemetery it could have been used to mark this. It may also have been used as a meeting place or a focus for ritual activity.

We then come on to the stone circle and another set of questions. What is a stone circle? In the context of Dartmoor, it consists of a ring or rings of upright stones, which are enclosing an open space. There are at least 18 examples of stone circles on Dartmoor, and it is known that several others have been destroyed. In the order of things the Merrivale circle is rather insignificant as eight of the other circles are over 20 metres in diameter with the largest being 39 metres. It is possible that the Merrivale circle is one of two known Dartmoor circles to have originally had a second ring constructed immediately outside the first. This type of circle is called a concentric circle. Of the stone circles that have been investigated, at every one a layer of charcoal was found covering the old ground surface, which may imply that fire played an important part of whatever ritual practice was being conducted at such sites. Sadly Merrivale was not one of the circles investigated so we can only assume that it conforms to the above findings. There has been a great debate as to whether stone circles were used as some sort of astronomical observatories and were used as calendars thus allowing their builders to calculate the changing seasons. This theory will be examined shortly but in this context, one word of caution. Many of Dartmoor’s stone circles have been the subject of examination during the 19th century when there were partially or wholly re-erected. In some cases the restoration may not have conformed to the original layout of the stone circle and may even have seen the inclusion of ‘extra’ stones to fill in any gaps, thus making any conclusions regarding astronomic alignments somewhat tenuous, a point confirmed by White, (2000 p.26).

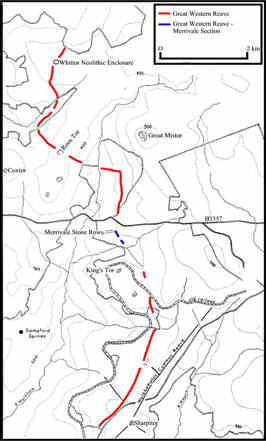

Although not part of the ritual context of the site it would be useful to briefly mention the reave which runs up the eastern edge of the complex. It has been suggested that reaves are the most characteristic features of Dartmoor’s prehistoric landscape, dating to around 1500BC. Today they are visible as low, stony vegetation-covered banks. Originally they were used to delineate different territories and zones. On Dartmoor over 125 miles of reaves have been identified and these enclose over 25,000 acres of land. Reaves provide evidence of a highly organised system of land division. The lower slopes of the moor were separated from the higher areas by ‘terminal reaves’ that followed the contours of the land. The lowland zone was then partitioned up into long narrow strips by ‘parallel reaves’. These strips were then subdivided by ‘cross reaves’. Effectively this divided the landscape into three zones – firstly the more intensively used areas represented by the parallel reaves; secondly, an intermediate area between these and the contour reaves; and lastly, above these, the highest and unenclosed land. It is possible that the varying zones indicate exactly how the land was used for grazing; the more productive pastures of the lower areas would be intensively farmed and therefore need more control of stock than the upland zone which may have been used as extensive, seasonal grazing. D.N.P.A. (2003 p.16). It was Andrew Fleming who in 1972 began work on the Dartmoor reaves and was responsible for their recognition. The reave running up through Merrivale was first brought to his attention when looking at a map of the area produced by Hansford Worth. On the map there was an ‘old bank’ marked. On inspection Fleming found that in fact it was a reave and although he was unable to follow the reave very far in the complex he did mange to prove it carried on in the ruins of Merrivale warren sited to the north. He then discovered that in a southerly direction it ran across Walkhampton Common. By a combination of his previous work and these new findings, he was able to establish that the reave ran for over six miles in length. He named this particular reave ‘the ‘Great Western Reave’, Fleming (1988 pp.42-44). A plan of the Great Western Reave is shown in figure18 below:

As can be deduced from the above, the various prehistoric features at Merrivale raise more questions than we have answers for. Partly due to the lack of modern investigation and partly due to the damage caused by man over the following centuries. What is clear is that the surviving monuments are evidence as to the importance of spiritual and ritual practices to their builders. It also indicates that in order to build such features there surely was a great deal of social organisation needed. The logistics required to plan, design and build structures that in some cases involved the movement of heavy slabs of granite, would test even today’s engineers. In order to organise a workforce capable of such tasks there would have had to be a person or persons with the ability to command and control. This alone, points to a structured society that contained a ruling elite, either secular or religious.

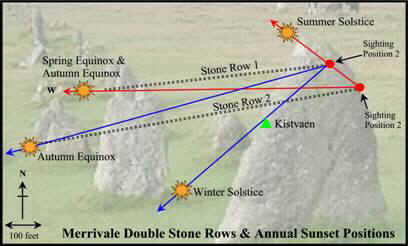

The second theory as to the possible use of the complex is that the stone rows were built to provide a series of astronomical alignments thus providing a calendar for the year. This would then enable them to accurately plan their farming year and other seasonal activities. This theory comes from an article written by Jack Walker (2003 pp.21-22). He contends that the two double stone rows are aligned with the setting sun at the solstices. The basis of the theory uses the blocking stone at the eastern end of the southern stone row (sighting position 1 on plan) as the sighting stone. This point is the “observation/recording platform. At the spring equinox (20th March) the sun sets due west, therefore if you are standing at the above mentioned point the western end of the Northern stone row is in exact alignment with the setting sun. He contends that originally there was another blocking stone in-situ at the end of this row, a fact first noted by Butler (1994 p.25). As the days pass the sun sets a little further east each day until the summer solstice (21st June) when standing at the sighting point the setting sun is marked by the northern row’s eastern blocking stone. Walker maintains that the way this was done was to walk along the northern stone row at sunset, as soon as the body’s long shadow aligns with the southern stone rows eastern blocking stone a marker was placed. If this was done on a daily basis it was possible to work out what time of year it was by noting which direction the alignment was moving in and then noting the relevant marker. Therefore if this process was started at the spring equinox (20th March) you could follow it eastwards until the summer solstice and then back westwards to the autumn equinox (22nd September) thus effectively providing a calendar for March to September. This is shown as the red alignments on the plan below:

From the autumn equinox the setting sun moves gradually south along the western horizon. If the blocking stone of the northern stone row is now used as the sighting position (sighting position 2 on plan) then at the autumn equinox the sun sets at the end of the southern stone row. The sunset on this alignment progressively moves eastwards until the winter solstice (21st December). So by using the same methods as above it should be possibly by using sighting position 2 to calculate the days from the 22nd of September to the 21st of December. Then as the sunset returns back along the alignment it would be possible to mark the days from the 21st of December until the spring equinox on the 20th of March. After that the sighting position is moved back to position one and the annual cycle repeats itself. These alignments are shown in blue on the above plan. The theory sounds plausible until the alignment for the winter solstice is examined. There is no existing feature for plotting this alignment. As shown on the plan all the other alignments end neatly with blocking stones apart from this one. Walker contends that as there is evidence that a cairn was built over the kist, A fact he cites from Butler (1994 p.30), this would have provided an artificial horizon to align with sighting position 2 at the winter solstice, therefore completing the calendar. The kist in question is the one marked ‘G’ in figure 3. Butler does not give any indication of the height of the cairn, only that it was 2.2 metres long. He states it was the largest cairn on Dartmoor but is this sufficient proof to provide a missing alignment? Walker concludes his theory by stating that due to the preservation of the Merrivale stone rows and the fact that the sun’s position relative to the earth has only changed by about 1º over the last 4,000 years, the accuracy of the alignments is virtually as it was in the year 2000BC. Which is fine, but I wonder why the people of this time would need to know in such detail what time of year it was. I would have thought that from an agricultural aspect there were enough natural indicators as to the time of year without having to go to the trouble of building a specific ‘stone calendar’.

Another noted supporter of this theory is Brian Byng. In his book ‘Dartmoor’s Mysterious Megaliths’ (pp.24-7) he suggests that there is an alignment from the stone circle to a notch on Middle Staple tor on the midsummer sunset. He also promotes the idea that a slab located 280 yds north of the road points to Pew tor and that there is a fallen menhir near to it. This gives an alignment to a ‘v’ shaped notch on the tor for the winter solstice. On his plan of the site he has managed to find three menhirs within the complex. As mentioned above one of these menhirs is above the present-day road and is amongst the northern hut circles of the settlement. If this is the case then this would extent the ritual complex considerably. No other authors make mention of this menhir.

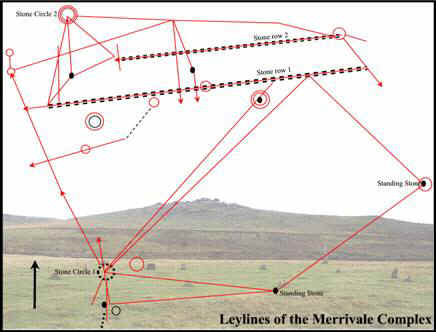

We have moved from the probable to the plausible so now let us move into the realms of the fanciful. That being that the features of Merrivale mark ancient lines track ways called ‘ley lines’. This subject has commanded hundreds of books and ideas and is in itself is a massive subject. Here is proposed to a very short summary of the principles of ley lines. In 1922 Alfred Watkins proposed in his book, ‘The Old Straight Track’ that ancient mounds of earth, burial places, prehistoric standing stones and old churches were built on invisible straight lines that stretched in all directions across the face of the country. These lines he called ‘ley lines’. His basic theory was that many ancient sites were purposefully built on these alignments. As time progressed the size of these alignments grew until it was suggested that they could not have possibly been the work of man. Therefore if man never constructed these alignments then alien life forces must have done so. The concept then moved on to astronomic alignments and also the fact that when some of the large alignments were plotted they formed huge landscape figures. It then was suggested that these alignments were often above underground energy sources or watercourses. This enabled dowsers to detect and plot the line of these energies. Sullivan (1999 pp 10- 18). Members of the Devon Dowsers have carried out such an exercise at Merrivale. In figure 20 below, the results of dowsing have been plotted on to a site plan of the Merrivale complex, Honeywood (2004 on-line source)

Bibliography.

Bulter, J. 1994 Dartmoor Atlas of Antiquities – Volume 3, Devon Books, Tiverton

Byng, B 19?? Dartmoor’s Mysterious Megaliths, Baron Jay Publishers, Plymouth

Crossing, W. 1990 Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor, Peninsula Press, Newton Abbot

D.N.P.A. 2003 A Guide to the Archaeology of Dartmoor, Halsgrove, Tiverton.

Fleming, A. 1988 The Dartmoor Reaves, Batsford, London

Gerrard, S. 1997 Dartmoor, Batsford, London

Glover, J.E.B, Mawer, A. & Stenton, F.M. 1992 The Place Names of Devon Part I, English Place Names Society, Nottingham

Hemery, E. 1983 High Dartmoor, Hale Ltd, London

Page, J. Ll. W. 1985 An Exploration of Dartmoor, Seeley and Co. London

Pettit, P. 1974 Prehistoric Dartmoor, David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

Sullivan, D. 1999 Ley Lines – A Comprehensive Guide to Alignments, Judy Piatkus Publishers, London.

Walker, J. 2003 Merrivale’s Stone Rows, Dartmoor Magazine, Quay Publications, Tavistock

White, P. 2000 Ancient Dartmoor – An Introduction, Bosssiney Books, Launceston

On-Line sources:

Honeywood, I. 2004 Prehistoric Circles and Stone Rows – A Dowsers Perspective, On-line source available at:

http://mysite.verizon.net/ianhon/index.htm

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Hi Tim – thanks for maintaining this excellently useful and often entertaining site. A question – in the first line of this entry, you refer to Merrivale as ‘the second most important ritual landscapes on Dartmoor’ – which are you thinking of as the first? I’m sure I’ll kick myself when you answer, but my mind’s totally blank.

All the best

Tom

In my opinion the Bellever/Lakehead Complex.

Aha. Thanks Tim.