One old tradition that still lingers on in the modern age is the ‘Goosey Fair’ which is held in Tavistock every year. In 1105, Henry I authorised the monks of Tavistock Abbey to hold a weekly Friday market. In 1116 the king issued a writ confirming the market-grant and adding a three day fair which was to be held on the eve, day, and morrow of St. Rumon’s principal feast which was from the 29th to the 31st of August. The market-grant in old law actually made Tavistock a ‘port’ which is a term borrowed by the kings of Wessex which meant a ‘trading centre’. It was later that the word port came to have its maritime connotations. Having become a port, the abbot then appointed a port-gerefa or port-reeve to oversee the markets and fairs. In later years the fair was moved to Michaelmas Day (September 29th), the calendar change of 1752 then moved the fair to its current date of the second Wednesday in October.

It is thought that at the time many of the tenants of the abbey would pay their rents in ‘geese’. These geese would then be gathered up and sold at a special market, hence the ‘Goosey’ or ‘Geese’ origin for the fair’s name. This in effect gave people the chance to buy their Christmas goose and then fatten it up for the festive dinner – “Christmas is a coming and the goose is getting fat…”

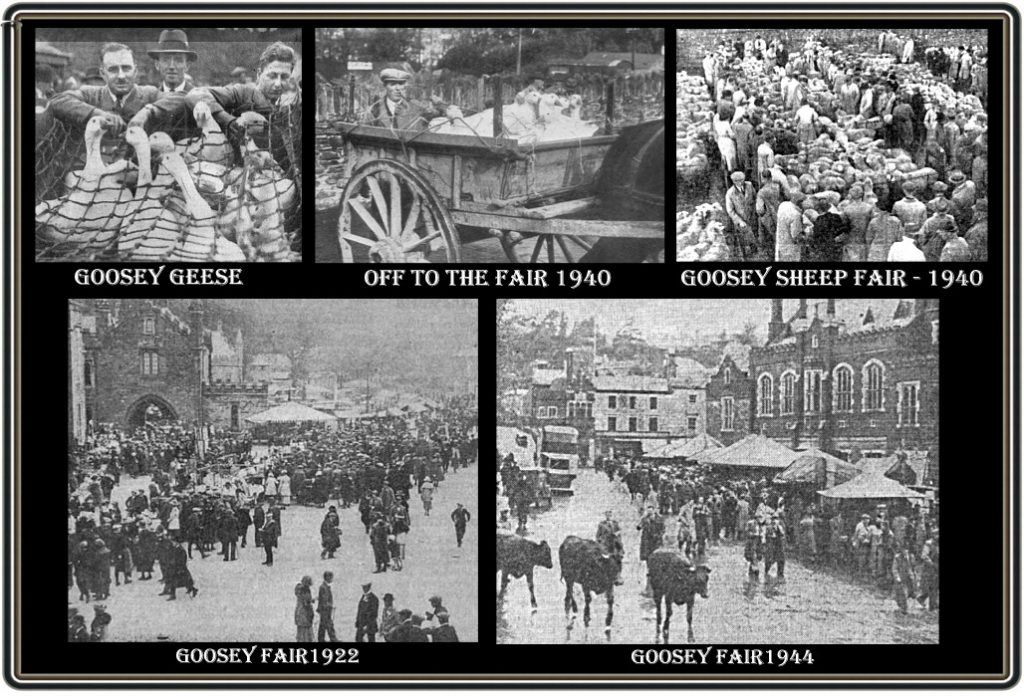

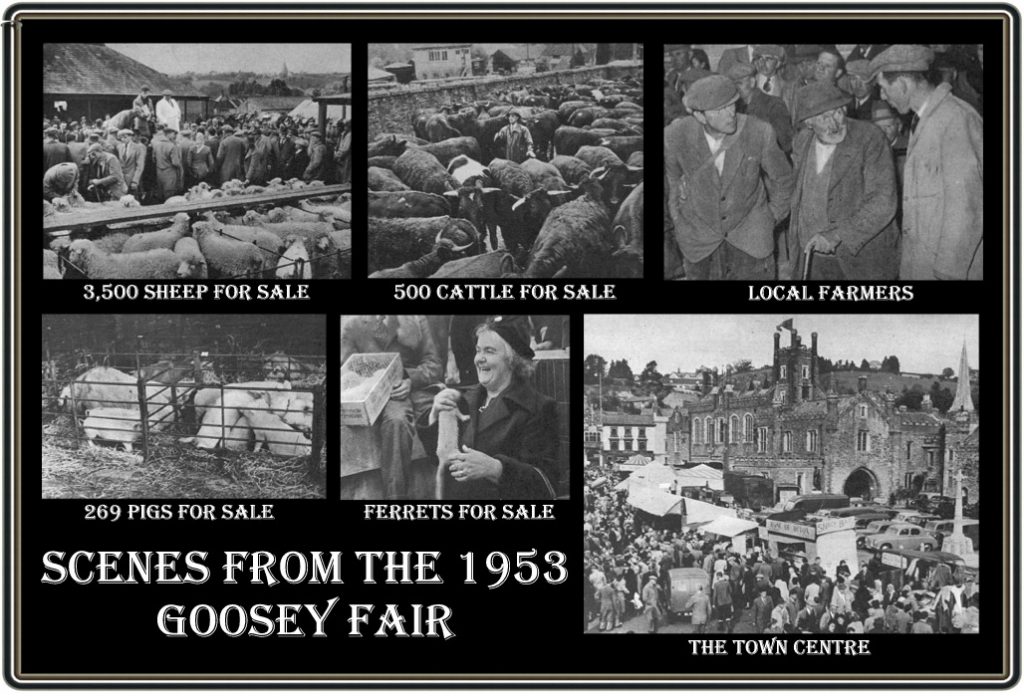

It was a later tradition that virtually all the inns in Tavistock would serve roast goose dinners and the meal became firmly associated with the fair. It has been thought that some unscrupulous people would take a day’s lease on a vacant shop and serve ‘cheap’ roast goose which was in fact rabbit dipped in goose fat. The atmosphere of the old fair must have been amazing, it is said that on the night before the fair the moor would be dotted with glowing lanterns as the drovers brought their flock and herds down to the town. The night air would be full of the sounds of barking dogs, bleating sheep, and lowing cattle as the drovers hurried them on in order to get to the market and claim the most prominent pens. Flocks of geese were driven across the moor from the numerous farms who throughout the year grazed them on the commons. In later years the geese were transported in carts and apparently it was nothing to see a queue of sixty carts all waiting to unload their cackling and honking geese. On this night, dressed geese would be taken to the pannier market to be sold to the town’s innkeepers and hoteliers in order to supply the next day’s roast dinners. During the mid 1900’s the auctioneers would treat all their farmers to a free goose dinner which sometimes would amount to 200 meals. Here is some good Devonshire advice from 1880 on how to choose a perfect goose for cooking; “Choose a young goose which is more easy said than done, as geese are frequently offered for sale when they are much too old to be eaten. The beast should be plump. the skin white, and the feet pliable and yellow. If the last are red or stiff, the bird is old or stale. Although Michaelmas is the time for geese, they are perfect in June; after Christmas the flesh is tough. A goose aught not to be eaten after it is a year old.”

The fair was also a time when copious amounts of alcohol was consumed and drunkenness was rife. It became a custom that sailors from Plymouth would come to the fair and end up in the White Hart where eventually the night would end in a massive brawl with the locals. This became an annual event and in the end the landlord took to removing the inn’s door in order for his ‘bouncers’ to eject the troublemakers easier.

A newspaper report from 1925 commented on the demise of the fair:

“Us used to cook as many as 30 geese, and now us doesn’t do nothing to it. It do be dying out. ‘Tes pity, but there ‘tes.” No one now remembers the old “Jan’s Vair” and Joan’s Vair,” of Tavistock, and, before long, “Goosey Vair,” into which the two have long been merged, will also be forgotten. In past years droves of geese invaded the town on the second Tuesday in October, to be sold and slain in their hundreds for Joan’s holiday the following day. Early in the morning sheep and rough moorland cattle and shaggy ponies flocked down the steep hills into the town. Toll which, until 1738, went to swell the schoolmaster’s purse was paid at the gates, and the monks exacted a toll of their own, swearing every merry maker not to curse and cheat, to lie or steal during the fair.

The civil authorities sceptical even in those days, instituted special courts to deal with those who forgot their oaths, “Pie Powder,” “Dustyfoot” was the name of these tribunals, which administered swift justice to dusty-footed pedlars, vagabonds, and other wanderers from town to town, from fair to fair, with no other possession in the land than the dust which covered their shoes.

Those were the days of the open house, before there were inns enough to shelter all comers, and householders were warned against harbouring any stranger for more than one night, on pain of being held responsible for his acts. The hospitable monastery was filled to overflowing, and even those who were obliged to sleep in the open among the booths always had their fill of ale and their share of the bird that was “too much for one and not enough for two.A ll that is changed now. As roads and means of communication generally improved, other times and means for sale and purchase were found, and new forms of amusement became popular, drawing away from the old, simple fun, class after class and filling the young people with an intolerant distaste for the amusements of their grandfathers.

At Goosey Fair, goose is no longer eaten. No toll, material or spiritual, is demanded from the hundreds who pour into town by charabanc, car, and train. Cattle are driven up to the market-place now and no longer tied to the churchyard wall, and the farmers are mostly wise men of the world, though here and there, like strangers in another country, stand little groups of cattlemen and shepherds from the heart of the moor – men with quaint hats, velveteen breeches, and full skirted coats of a bygone fashion; men whose hair is long and bushy, and whose brilliant, unaccustomed eyes survey the scene with a slightly quizzical, wholly detached air of interest.”

A similar report on the fair appeared a few years later:

“Someone told me before I started that Tavistock Goose Fair is not what it was. If he meant that the crowds of today take their pleasure more sadly, that the cheap jacks formerly were more imperious and more successful, that Devon countryfolk were less cautious in looking at bargains, that itinerant musicians, deserving and otherwise were more persistent, and that money flowed more freely, then after my experiences of yesterday, I can only say that Tavistock Goose fairs of the pst must have been fearful and wonderful institutions. Old habituals of the festival, who count their years not by their summers or their winters, but by the number of ‘Goosey Fairs’ they can remember, told me the crowds seemed much as usual, and nothing was changed except one thing – they could not find the geese. Neither could I. The goose market used to be held the day before, but this Tuesday there was none. The old stagers aforesaid talked of the palmy days when they could pick up a fine bird for four shillings. Now, alas, the cheapest of cheap jacks had no such bargains to dangle before the suspicious eyes of his pastoral audience. The best we could do yesterday, if we chose, was to partake of a goose dinner at five shillings a head. Some of the refreshment houses had such on their bills of fare, and tables were laid in the market, where over forty birds were available to be cut up. Buts as for going home from Tavistock with a succulent Michaelmas bird at five shillings or fifty shillings it was not to be.

The power of attractions of the vent over the whole countryside, and down to Plymouth itself, seemed undiminished. In spite of extra coaches, all trains were crowded, so much so that at the times of departure even Friary passenger station looked busy. Motor coaches and old style waggonettes, and even a four-in-hand brought hundreds more. The little town was thronged all day. To thousands of folk from miles around it was, as it had been from time immemorial, one of the holidays of the year. The visitor could not go far before being drawn into one or other of the whirring eddies of excitement. As soon as he left the station he was confronted by familiar cripples, with musical instruments, who pressed upon him their hearty good wishes for the best of luck – and collected toll from him. Neat dainty nurses made a more agreeable levy in exchange for primroses – primroses, October? – on behalf of the Tavistock hospital. A few yards further and he was up against the outpost line of philanthropists of compelling mein industriously forcing on a somewhat reluctant public, singularly blind to profit making opportunities, complicated and more than hazy bargains in watches. The professed love of these gentlemen for their fellow mortals was comparable only with the distaste of the majority of them for bacon. There were half a dozen or more of these jewellers’ salesmen, all with identical assortments of goods, and with identical methods and identical phraseology with which to commend them to the public…

As one advanced further, stolid battalions of cattle in massed formation advanced as to the attack, while flank guards of sheep skirmished about ones knees, and sportive countrymen, anxious to display the qualities of their equine friends, whether tiny Dartmoor pony or lanky hack, put the populace through what the physical training instructor in one’s army days would have called ‘quickening exercises’. Eventually the visitor, having evaded the cavalry, side-stepped from the advancing sturm-truppen of fiercely horned cattle and avoided the shipwreck on the backs of solid looking sheep, found all he had previously seen repeated in bulk in the stock markets. There were the cattle, the sheep, and the horses, little pigs with big squeals, sheepdogs either blatantly assertive or wistful and fed-up, calves a few days old, at leat one cow whose udder would have stirred an R.S.P.C.A man if he could have seen it into considerable activity, the same collection of philanthropic jewellers, and men with bargains of ready-made clothing of ‘pre-war manufacture.’ The last found, it is feared, a dull market, there being no response even for thirty shilling trousers reduced to eight shillings and sixpence. Once more with this Devonshire crowd, it was a case of cherchez la femme. It jibbed at elegant check trousers for its adornment, but many young men succumbed to the allurements of seven guinea wristlet watches at three and four pounds for their wives or sweethearts.

In another quarter of the town the blare of steam organs blatant with ‘Colonel Bogey’ and other popular marches announced that the juveniles were busy on the roundabouts and swings. Here there were pressing invitations from numerous young ladies to try one’s luck with the rifle or at hoop-la or the coconuts. There were also tempting offers to go and see Ursa, the bear woman, also a mermaid and the most beautiful artist’s model from Paris. Amid all this gaudy and noise display was a traction engine, the shining brass-work and spotless cleanliness of which excited much comment, It could be guaranteed to reduce the most fastidious of inspecting military martinets to silence. Altogether it was an amusing day, but, except on the lunch table, there was no goose.” –

It was the laws on fowl pest that finally put a stop to the tradition of selling geese at the Goosey Fair, when live poultry were forbidden to be sold at markets. This was in light of a serious outbreak of Newcastle disease in the late 1950’s, early 1960’s which wreaked havoc amongst the poultry industry.

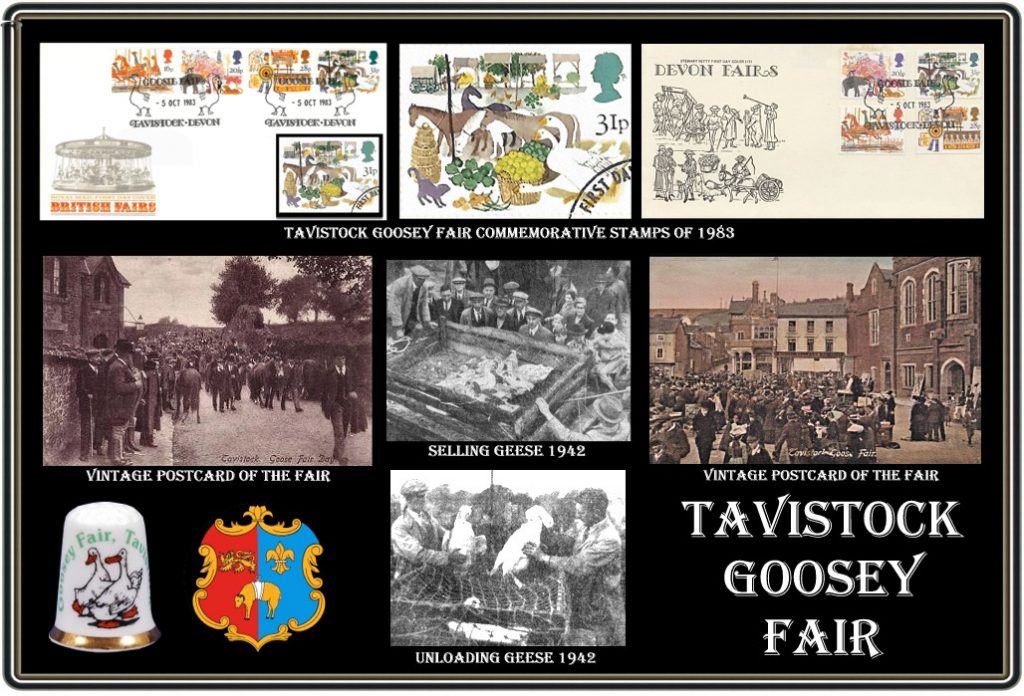

The Tavistock Goosey fair was commemorated by the Royal Mail in 1983 on a hideous 31p stamp of a set celebrating the 850th anniversary of St.Bartholomew’s Fair. There was a special ‘Goosie Fair’ first day commemorative issue for Tavistock (see above) – lick that if you can!

There is a well known folk song called Goosey Fair which some consider to date back centuries, others however say that it originated in 1920’s when the song was written for a pantomime that was being held at Plymouth. I have now been informed that the song was written in 1912 by C. J. Trythall as a token of his love for Devon and was originally composed for vocals and piano.

Goosey Fair

Tis just a month come Friday next, Bill Champerdown and me,

Us traipsed across old Darty Moor the Goosey Fair to see,

Us made ourselves quite fiddy, us greased and oiled our hair,

Then off us goes in our Sunday clothes behind old Bill’s grey mare.

Us smelled thic sage and onion ‘alf a mile from Whitchurch Down,

And didn’t us ‘ave a blow out when us come into the town,

And there us met Ned Hannoford, Jan Steer and Nicky Square,

And it seemed to we all Devon must be to Tavistock Goosey Fair,

Chorus:

And its oh, and where be a-going,

And what be a-doing of there,

Heave down your prong and stamp along,

To Tavistock Goosey Fair.

Us went to see the ‘osses and the ‘effers and the yaws,

Us went on all them roundabouts and into all the shows,

And then it started raining and blowing in our face,

So off us goes down to the Rose to ‘ave a dish of tay.

And then us had a sing song and the folks kept dropping in,

And what with one an’ t’other, well, us had a drop of gin,

And what with one an’ t’other, us didn’t seem to care,

Whether us was to Bellever Tor or Tavistock Goosey Fair.

Chorus:

And its oh, and where be a-going,

And what be a-doing of there,

Heave down your prong and stamp along,

To Tavistock Goosey Fair.

‘Twere raining streams and dark as pitch when us trotted ‘ome that night,

An’ when us got past Merrivale Bridge, our mare, ‘er took a fright,

Says I to Bill, “Be careful, you’ll ‘ave us in them drains,”

Says ‘e to me, “Cor bugger,” says ‘e, “why ‘aven’t you got the reins,”

Just then the mare ran slap against a whacking gurt big stone,

‘Er kicked the trap to flibbits and ‘er trotted off alone,

And when it come to reckoning, ’tweren’t no use standing there,

Us ‘ad to traipse ‘ome thirteen mile from Tavistock Goosey Fair.

There was an old saying; “If deer rise up dry and lie down dry on St. Bullions day which was the 4th of July then there was a good goose harvest to look forward to.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

One comment

Pingback: Michaelmas | gallybeggar