Today we have the luxury of instant communication with the benefits of email, online news coverage, and mobile phones etc. on and around Dartmoor. But how was this achieved in days long gone by in such a remote area? I think the answer would be very, very slowly if at all and then mostly by word of mouth. In 1782 a theatre and businessman called John Palmer had a “cunning plan.” He proposed to the British Government that he would create a network of mail coaches to carry mail, passengers, and news between the country’s major cities. The Government saw the benefits of such a network and in 1784 the first experimental route was established between London and Bristol. It did not take long before the network was expanded with mail coaches connecting many of the cities and towns across the country. By 1795 Palmer had established himself Controller General of the Mails. As the The whole concept was built on the basis of providing a fast and efficient service that would benefit businesses, Governmental communication and the population in general. In order to do this there were several vital components to the plan, the coaches needed to be designed for speed, endurance, and capacity. Skilled drivers and guards along with teams of strong and resilient horses were also a must. At the time one John Vidler was supplying mail coaches and refinements were made to them which made for better speed and comfort. The framework of the coaches was made from a lightweight ash frame which had adjustable leather suspension thus making for a faster and more comfortable ride. Externally there was a seat for the mail guard at the back and a roof seat along with the coachman’s seat. The undercarriage was of a robust construction which coped easier with any rough road surfaces. A further innovation was later provided by the ‘Mail Axle’ which were fitted with small external oilers which allowed for on the road maintainace. As a further precaution spare wheels and parts were kept at posts along the mail routes. What may seem alarming is that there were no brakes fitted instead a drag shoe would be used on steep inclines.

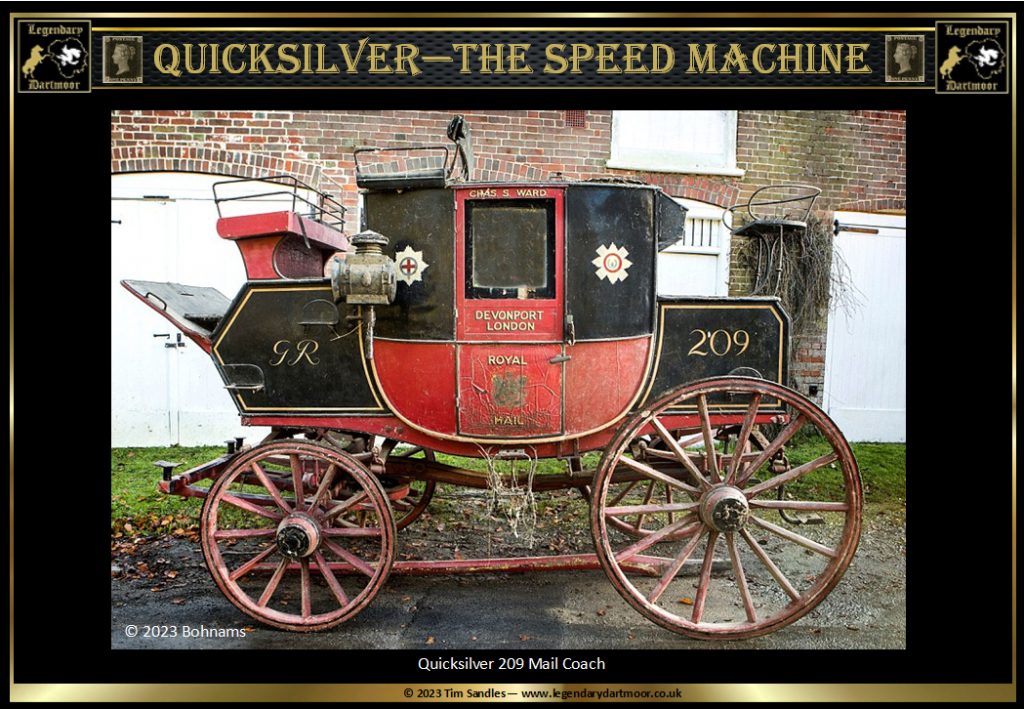

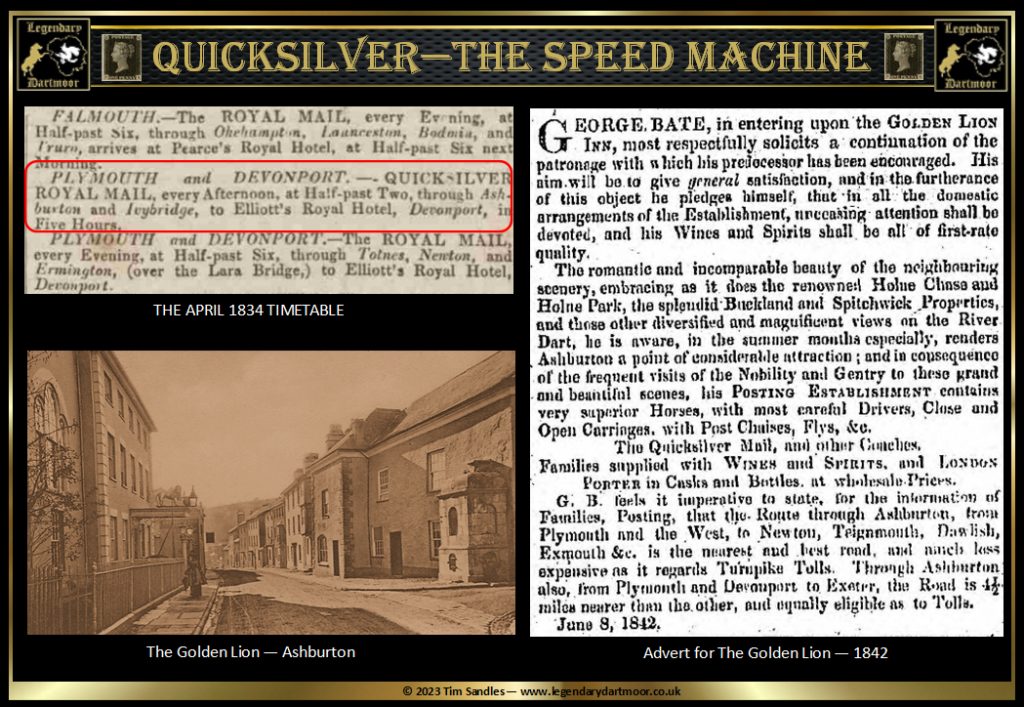

All the mail coaches were identified by a number except one which was deemed to be the fastest and efficient, this along with its number 209, earned the name of “Quicksilver” and ran between London and Devonport. In the main most of the postal route would be driven at night as there would have been less traffic to hinder its progress and obtain more speed. Said to travel at an average speed of 10mph which included an allowance for the change of horses, guards, and coachmen as well as delivering the mail to the post offices on the route. The target time on a good run for the Quicksilver was to travel the 219 miles from London to Devonport in 23¾ hours with its record being 21 hours and 15 minutes. So punctual was the arrival of the coach that town clocks were set by the awaited arrival. Should the coach arrive more than one minute late then it was possible that the guard would be fined. In a Dartmoor context one of the main stopping point from London to Devonport would have been Ashburton. The major posting house in Ashburton was the Golden Lion Hotel and as can be seen from the advert below it was one used by the Quicksilver and its horses. Also evident is that the hotel was well equipped to cater not only for the passengers, guests but also ran local coaches of their own. In 1837 a gentleman in London enquired to a hotel waiter what was the best coach to take him to Exeter. The waiter replied “The Quicksilver Mail sir! one of the best out of London – Jack White and Tom Brown, picked coachmen over the ground – Jack White down tonight.” He was then asked if the coach was guarded and relied “blunderbuss and pistols in the swords case; a lamp each side of the coach and one under the floorboard – see to pick up a dropped pin in the darkest night of the year.” In 1823 one passenger gave a detailed description of the Quicksilver coach he rode in “It was a sturdy, business-like vehicle for strength and speed rather than accommodation. A rather broad squat body, with small doors and windows, scarlet, upon stout scarlet wheels, the fellies and spokes as broad as can be; the hind boot sloped down somewhat to the rear carrying the guard’s cosy round-backed perch, where he sat guarding his mail bags – no other seat being allowed at the rear. In a long leather tube at the side of the seat rested the post horn; and I can remember that before the railway reached Exeter, about 1843, a similar holster carried a blunderbuss.” In the February of 1830 the Sun newspaper were desperate to get editions of their newspaper to Devon in order to beat their rivals in delivering the news of the King’s Speech by mail coach. Unfortunately things did not go well and they were defeated by the Morning Journal. They admitted that “by an unfortunate mistake they (the papers) were given to the late mail instead of Quicksilver,” such was its reputation. At this time a coach driver was often referred to as “Jehu” which had a biblical etymology. According to the bible ‘Jehu’ was a commander of the King of Israel’s chariots famed for his driving speeds and tenacity. So popular was the Quicksilver that the service was often promoted in adverts for the sale of inns and hotels along its route. In the May of 1838 the Pear Tree House at Ashburton was up for sale and its advert read “the grounds adjoin the Great Western Road, which is passed by the Quicksilver Mail.” Clearly the “need for speed” was very much reliant on the condition of the roads along its route. Any improvement in these would quite often cut minutes off the Journey. In the July of 1838 the Ashburton Turnpike Trust announced that their road improvements had been completed between Ashburton and South Brent. This four mile stretch was estimated to knock fifteen to twenty minutes off the Quicksilver times. It was not unusual for anonymous inspectors to ride the coach in order to monitor the performance and time keeping of the journey – should things be not up to standard consequences soon followed.

No matter how good the roads or how experienced the coachmen there were times when accidents occurred. In the October of 1816 the Quicksilver was on its way back to London and had reached Salisbury. As he pulled in to the Pheasant Inn the unbelievable happened, a lion had escaped from a nearby traveling menagerie and pounced upon the off-side lead horse. All the passengers bolted into the inn leaving the coachman and guard to deal with the beast. The guard drew his blunderbuss and was about to shoot the lion when the owner suddenly appeared. He begged the guard not to kill his valuable asset and instead offered his dog to the lion which satisfied its hunger and the horse survived. In the September of 1839 the Quicksilver had left Plymouth and was about two miles from Ashburton when it met two ladies riding two up and side-saddle on their horse. As the speeding coach approached close to them they both fell off their mount and unfortunately the driver was unable to stop the coach in time and one of them went under the wheels with a fatal outcome. Another hazard the Quicksilver coach had to face was the bad weather and especially the snow. It was reported in the February of 1841 that the Quicksilver mail should have arrived at Ashburton by Saturday noon but did not turn up until the next Sunday evening. This was due to huge snowdrifts up to fifteen feet in height were covering the road and making it impassable. At one spot along the way the guard and coachmen had to take Quicksilver through a field and over a wall to regain the normal road. The only way the mail finally got to town was by transferring the mail bags to men on horseback and even then they did not arrive until midday on the Sunday. Another embuggerance to Quicksilver were the narrow Devon bridges which were not designed for such coaches or speeds. In the April of 1833 a committee hearing was discussing the state of many of these bridges. As an example the New bridge over the river Plym at Plympton was cited – “its situation is extremely dangerous, insomuch as it runs at right angles to the road. The approach from Exeter is very difficult to be discovered on a dark night in consequence of it being hidden by two walls. The mail coach has to pass over this bridge twice a day – the Quicksilver, which derives its name from the extraordinary rapidity of its travelling, and it will be remembered that this coach has but four and a half hours allowed to perform the distance from Exeter and Devonport, consequently passes over this bridge at the rate of ten to twelve miles an hour. From the acute angle from which it is turned off, it is almost impossible to see it, and from personal observation, and having met with several accidents myself, I can speak of its danger.” – The Western Times, April 13th, 1833.

The coming of the railway networks hailed the gradual demise of mail coaches in the late 18th and mid 19th centuries as they provided an much faster and efficient way of delivering the mail. Clearly they were not dependant on the road conditions, other traffic, turnpikes, horsepower, and to some extent the weather, and also were capable of carrying larger cargos. The faithful Quicksilver 209 finally took its last run in 1847. However, on the 10th of December 20th 2015 Quicksilver reappeared like the Phoenix rising from the ashes at an auction held by Bonhams where it was expected to reach around £70,000. The coach was deemed to be the last surviving mail coach of its time hence the expected asking price. According to the auctioneers the final winning bid of £133,660 which well exceeded the guide price and came from a private owner. Quicksilver was then sent to the Fenix Coaches based at Clayhidon in Devon for restoration. It was estimated the project took two years and involved over 3,000 hours on research and work to complete. Any parts which needed replacing were traditionally remade, the upholstery material was specially woven and externally 22 coats of paint along with 80+ pages of gold leaf were applied. When completed there was an official unveiling ceremony held at the Guildhall in London with a later one held back in its old stamping ground in Devon.

Imaging walking along the main mail routes back in the day, it must have been a wonderous sight to see Quicksilver and its team of stout horses thundering along the road. In all likelihood you would have advance warning of its approach by the trumpeting of the post horn. The sheep in a nearby field continue contently grazing and not a head looks up to see what’s astir, they hear the same everyday and are well accustomed to the disturbance. One of its purpose was to warn turnpike gate keepers to open the gates and clear any obstructions as the coach was not stopping for anything, it had a timetable to keep. Then the black and maroon coach comes into view trailing a dust cloud behind it, the coachman gives a quick thoughtless flick of his whip whilst he chats to the passenger sat beside him. Some well dressed gents and lacy frocked ladies sit haughtily inside the cab and give the odd inquisitive glance out of the windows. The guard cheerily waves on passing and as the dust settles you can easily make out the odd spark or two as the horse’s shoes clatter over some stones – then in an instance it’s gone. Thoughts cascade through your mind, what news was it carrying in those mail bags? where were the passengers going and for what purpose? I wonder if it will be on time – no delete that one, it’s always on time, well nearly always.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor