In the July of 1916, the Government introduced the Home Office Scheme whereby Conscientious Objectors were given the chance to leave prison and work at designated labour camps called “Work Centres.”. It was announced that from the 1st of March 1917 “Dartmoor Prison will be closed for convict prisoners and occupied by conscientious objectors, who it is surmised, will be employed on the reclamation scheme initiated by the Prince of Wales on the Dartmoor portion of his Duchy estate.” It was estimated that originally around 1,000 Conscientious Objectors went to Dartmoor prison. One such was Joseph Hoare who remarked “They carted out the remaining convicts from Dartmoor and opened that up and invited volunteers. First of all from amongst Cos and I wanting to get alone, I went to Dartmoor where in one’s off time, of course, sometimes you could wander over the moors for miles without seeing anybody at all! And the work that I was put on there was looking after the fire engine which was a very cushy job. They paid us eight pence a week of something like that. “ – The Imperial War Museum, online source. However, a year later it appears that the Home Office Scheme was not quite what it was meant to be.

SEPTEMBER 1917 – “The Conscientious Objectors’ Committee at Princetown issued a statement pointing out that those who accepted the Home Office Scheme did so believing they would thereby perform work of real value to society under normal civil conditions. But they find on the contrary that the work is economically wasteful and, both in its character and the conditions under which it is carried on, is the same as that given to Dartmoor convicts.” – The Woman’s Dreadnaught, September 22nd, 1917.

SEPTEMBER 1917 – “There are a few hundred right good young fellows, at least that is my view of them, wasting their time in Dartmoor Gaol… It is hard labour all the time. These young fellows who are there are men who have done time in prison because they happen to be troubled with what sometimes the nation lacks, namely, a conscience. However, these young fellows also feel taht5 they are wasting their time and may be doing useful work for the nation, if the nation would let them.” – The Yorkshire Factory Times, September 27th, 1917.

What now follows is an account written by an inmate of Dartmoor prison the very next day of the article above. I think it gives a good insight of the sentiments of those conscientious objectors of the time. Although a contentious issue it does reiterate how at a time of war and strife many men with talent and skills were wasting their time doing menial tasks when they could be best employed elsewhere.

“The rain has fallen mercilessly since daybreak. A dense drifting mist obliterates the outer world. A fierce nor’-easter gale sweeps over the moor and screams with fiendish glee as it dashes itself against the prison walls. The slates rattle upon the roof. Miserable as are the outside conditions, still more miserable are the conditions within. Rain trickles down the dirty whitewashed corridor walls, eventually settling down in little pools in the crevasses and hollows of time-worn flagstones. Little piles of dust, paper, and matches lie at the door of almost every cell. Green, bilious-looking blankets, red striped arrow-bespangled sheets hang dangling in disorderly profusion over the corridor rails as far as the eye can see. This is Dartmoor as it appears to me, on this 28th day of September, in the nineteenth hundred and seventeenth year of our Lord. As I gaze round my little cell, its four bleak whitewashed walls, its cold grey floor and ceiling, its bolted door and iron-barred window, my heart becomes sick, for I am reminded of the slothful progress of humanity. A hundred and four years ago today, and this self-same cell was probably occupied by an American prisoner of war. And here it stands today, unaltered, even by so much as a nail. Behind these bars a few months ago the wild-spirited Sinn Feiner fought for liberty, and here I suffer for it today; and who knows but some poor soldier who fights for it today may pine for it here tomorrow. Strange it is but true, “The road to Liberty lies through the prison gates.” Sixteen months ago I was arrested, and since I have been in five different prisons – Kilmarnock, Ayr, Barlinnie, Wakefield and Dartmoor, and if there be degrees of rottenness, this easily is the most rotten. We are away out on the bleak, lone moor (1,300 feet above sea level) completely isolated from human society. It is the dreariest of dreary places. Nothing but moor, moor, as far as the eye can see.

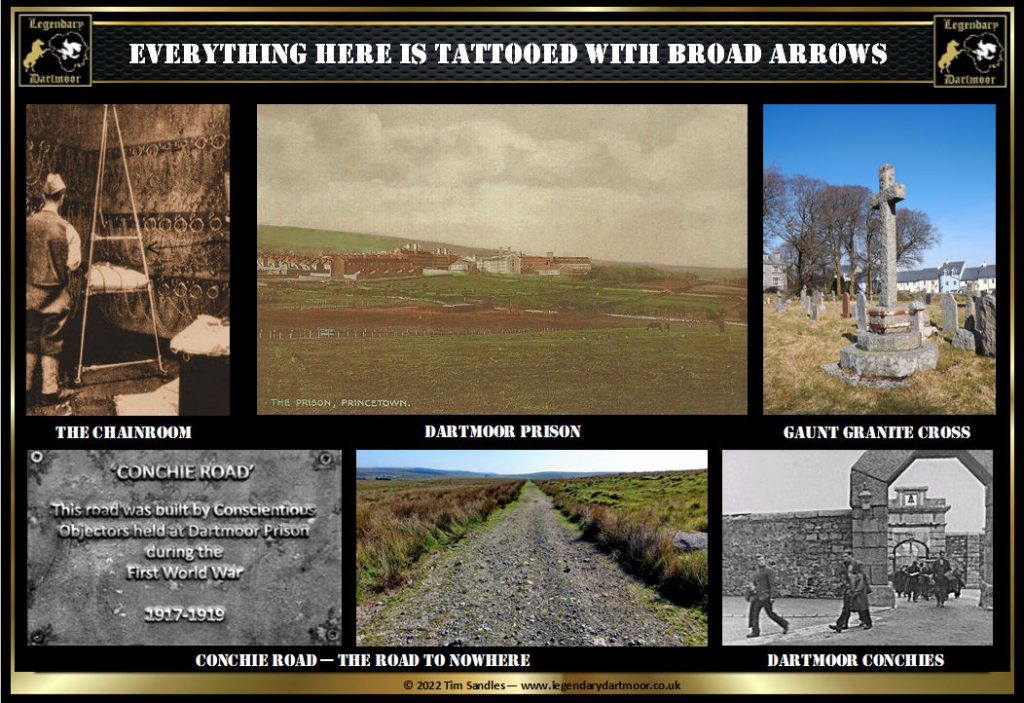

To give you an idea of the place, let me tell you, that only once in the history of the prison has a prisoner make a complete escape. Many have tried it, but have either returned half staved, half mad and begged to get back., or (I am told) have been found away down in the deep black gullies, cold, stiff, and dead. This is a terrible place for a man of sensitive, imaginative temperament. To peep into a punishment call, with its three doors, against which a man mad with suffering could kick and scream unheard till he fell unconscious or dead. Or to peep into a chainroom with its handcuffs, ankle chains and all the other implements of torture makes my flesh creep and my heart thump. Sometimes when I think of it all my wrath boils and surges through my whole body and threatens me with a white fire; and only when I enter the quiet, calm, neglected graveyard, do I return to sanity. They lie, “star-spangled on the grass,” unknown uncared for, – the victims of a cruel age. Man is cruel, but nature is kind. She never forgets. The grass, bright with the dew of the morn, shivers and casts its tears upon the parched earth. The robin chirps pensively from her bough. The ivy rustles eerily on the wall. A gaunt granite cross casts its shadow across the graves, and all is quiet. No more these ears shall hear the tyrant’s threat, nor eyes behold the captive bars, for they are free, free, free – free in death! Beyond this place of wrath and tears they smile pityingly upon a poor captive world.

But this is the dark side of Dartmoor I have shown you. Dartmoor of today has another side, bright to dazzling point, and the man who does not find humour here would not find salt water in the sea. We have here almost forty different religious sects and political parties. We have Quakers, F.B’s, I.R.S.ers, L.L.P.ers, Christian Scientists, Atheists, Salvationists, Anarchists, Deists, and heaven only knows what we haven’t got. On one door you will see a notice “Jesus saves,” on another “Please leave no tracts – already saved,” another “There is joy in heaven,” while on the door opposite and Atheist will ask, “And here the hell’s haven.” Just now as I write all are praising God in their various ways. Some are singing, some are praying, some are preaching. A Welshman beneath me sings with religious fervour. “The land of my fathers.” Down in the yard a dozen poor shivering creatures are standing in the rain singing “Away over Jordan.” Hundreds are wishing they would go over Jordan and sing it. A cornet, two concertinas, two fiddles, and a clarinet are going full blast, each at a different tune. Irreligious Englishmen and heathen jews are frying sausages, onions, and cheese. Others are washing socks, shirts, and other garments. There are over a thousand of us here, and a more unique collection never dwelt under one roof. We are engaged on “Work of National Importance!” I have followed many occupations since coming to this scheme, viz., sack repairer, rope maker, mat maker, drainer, wood cutter etc., and after a year’s experience I never yet witnessed such wilful waste of public money. Fancy farmers making mailbags, trying oakum and mat making when the nation is supposed to be in a state of siege. If this Government does not come out of this war with clean hands, there is no reason why it should come out of it with dirty feet. We have doormats that would stretch from Merthyr to Melbourne, mail bags that would dry up the Atlantic if thrown in, rope enough to tie the world in knots. The motto of the scheme seems to be “All you who can make things of use, make things that are useless.” But my fingers are growing cold, so I think I will creep away under my broad arrows. Everything here is tattooed with broad arrows, from our bedclothes to our prayer books. I always look to see if they are not breaking out all over my body. I shouldn’t be surprised if they did.

There is very little evidence today of the “useless” mail bags or ropes made back in 1917 but there one or two lasting “useless” reminders – ‘The Road to Nowhere’. This road starts at Bullpark on the outskirts of Princetown and then runs for 1.69km across Royal Hill where it ends abruptly. There is no rhyme or reason for its construction and it was built by the Conscientious Objectors between 1917 and 1919. Today it is known as “Conchie Road” and a commemorative plaque at its beginning reads “Conchie Road – This road was built by Conscientious – Objectors held at Dartmoor prison – during the -First World War – 1917 -1919.” To the north of the prison there is a long section of wall which is known as the “Conchies Wall” and a nearby field called “Conchies Field.” Both seem to have been pointless initiatives intended more as a punishment than an improvement to the land.

The Song of the Ropemaker

We’re workers of National Importance,

To you of failing hopes we whisper hope,

Though Rhondda should fail to find you rations;

Fear not, dear friends, while we are making rope.

What though your crops upon the land should perish

What though your imports sink beneath the wave,

This hope within your bosom fondly cherish

We boys at Dartmoor still have power to save.

Let croakers croak and prate about starvation,

Remember “Man lives not by bread alone,”

We’ve rope enough to hang the blessed nation,

A yard or two will see you safely home.”

The Pioneer, November 13th, 1917.

If you would like to explore the story of the Dartmoor Conchies further then I can thoroughly recommend Simon Dell’s book – ‘The Dartmoor Conchies’, 2017, The Dartmoor Company.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

I walked that road this morning as part of a longer walk. It was a blanket of mist and rain, and cold wind. I had modern waterproof jacket and trousers, boots etc. I was still soaked at the end. I pity those poor souls forced to work 6 days a week to build that pointless road in all weathers, with the outdoor clothes they’d have had back then.