In the Autumn of 2022 the Devon County Council submitted a Strategic Outline Business Case for re-instating the old Plymouth to Tavistock railway line. At onetime this service was run by the Great Western Railway Company and provided a vital link for people wishing to visit Dartmoor from Plymouth and then return. Now follows of an account from 1899 whereby the journey from Plymouth to Princetown is described along with the various sights and scenes around Princetown at the time.

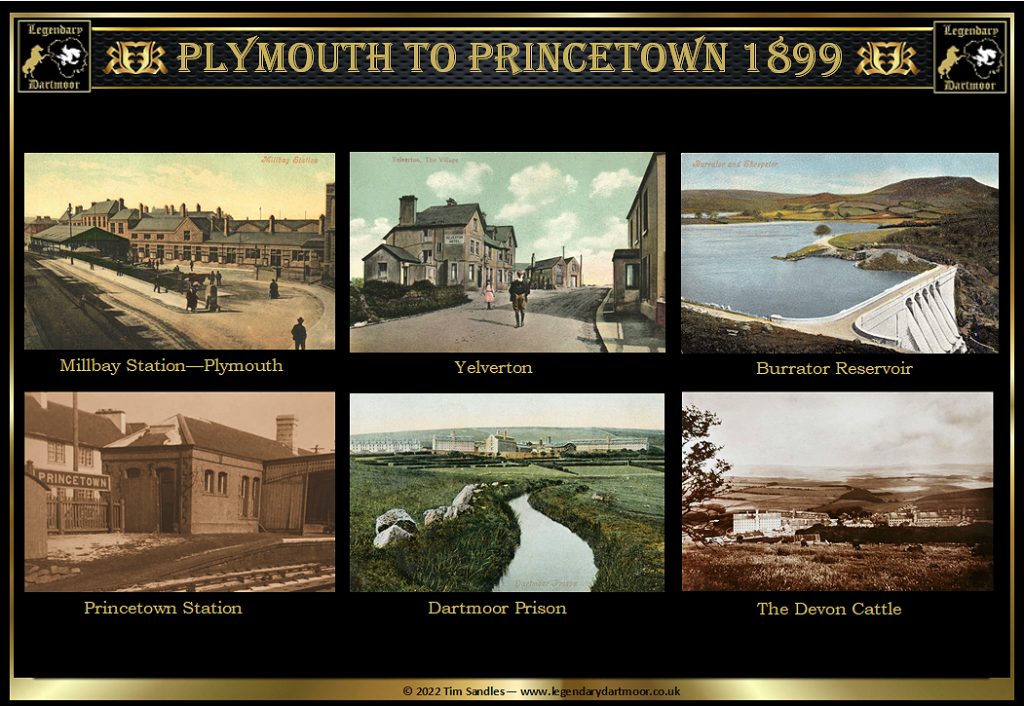

“We travel by the winding branch of the Great Western Railway line which runs upward from the level of Millbank to the wild heights of Dartmoor. As we take the journey, the train speeds up the slope, on past the verges of mountain woods in which the Spanish chestnut casts it umbrageous shade, and in which the silverly birch rustles in its late summer splendour. Down below in the fast-receding valleys one catches glimpses of rippling streams, clear as the sunlight which bathes them and the woods and water in gorgeous splendour. Higher up, the hazel and beech begin to show the tinted traces of autumn. We pass through a stone cutting on the grey sides of which ferns are nestling. Once again we emerge into the open country, where in the lush meadow, the brown Devon cattle are swishing their fat sides in the shade of oaks and beeches. Beyond in the distance, miles up the height, one catches a glimpse of the purple heather and the wildness and barrenness of Dartmoor. From this point the vegetation of the lowlands gives place to that of higher altitudes. The slopes on each side of the railway line are covered with birch and broom and mountain flowers. There is a little copse, the deep bracken is changing its colour from olive green to pale and yellow, deepening also into browns, reds, and scarlet. The jagged cliffs begin to peep through the woodlands. We scoot through a tunnel and emerge in a blaze off sunlight, of tinted bracken and yellow gorse.

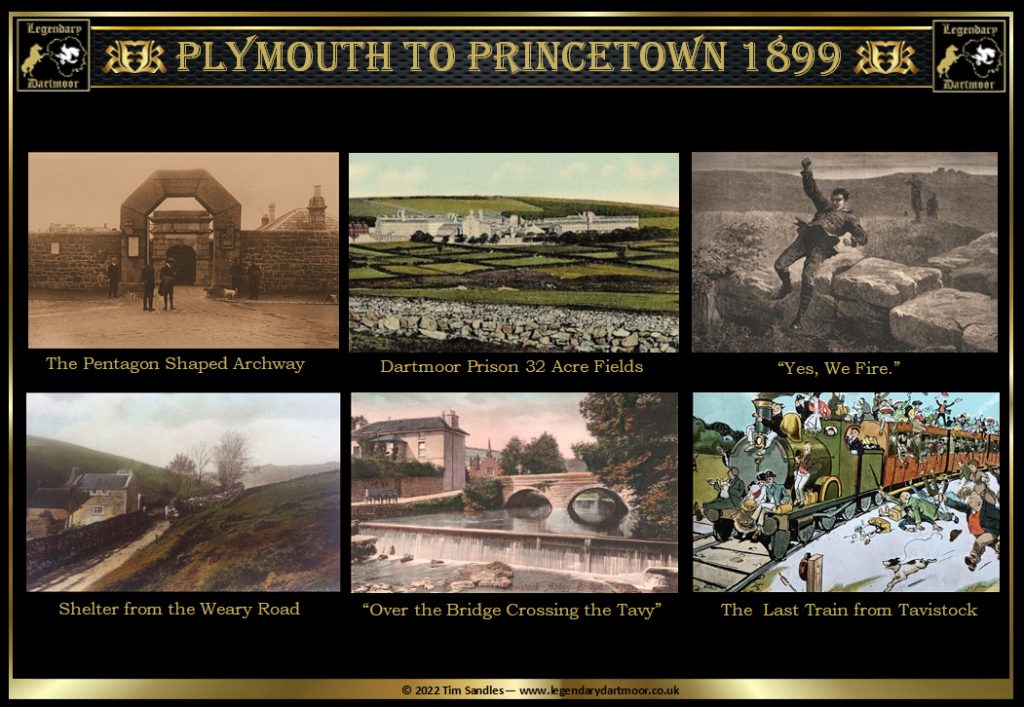

Beyond Yelverton our line takes a curve. We look backwards down the valleys, and trace the outlines of the streams from their courses to the sea. Behind us the house roofs and windows of the village are flashing the glories and unclouded sun. We pass once more by stream, woodland, and marshland. We skirt Burrator, the new Plymouth reservoir striated with the breezes. From our vantage ground we look southward to the Hamoaze and the salt waters of the English Channel. Our course is once more widening. The railway line runs in and out along the slides and slopes of the hills. We cast another backward glance as we leave the train at Princetown. The cliffs and woodlands have now given place to bare hills and rounded slopes, the colours of which vary from brown to purple, merging under the shadowed crest, into purple-black. We are now close to the convict prison of Dartmoor. It is Saturday afternoon, and the convicts are not engaged in their usual occupations. The fields lie vacant, the quarries silent. There are traces of labour on the hillside in land half reclaimed from the waste or rock and moor. Below us the crops are ripening. In walking around the prison walls we pass the guard-point, from which a watchful warder commands a view of the farm, the entrance to the quarries, and the far distant fields and hills. We walk to the farm, where a posse of convicts is engaged in milking cows. The entrance to the farmyard is barred by a warder who marches sentry-fashion with half-cocked and bayonetted rifle in hand. One or two of the prisoners cross from the shippon to the stables. They are clad in buff Scottish cap, blue cotton overalls striped red, dark trousers, and greyish buff leggings, each garment being plentifully splattered both with the marks of agricultural life and with the broad arrow of the government. They are bronzed, healthy, active fellows, and they glance keenly and openly at the visitors. They have the bearing and appearances of smart farm labourers. The warder informs us that they belong to the well-behaved class, and that in a year or two their time will have expired. A herd of Devon cattle are driven out of the yard. A warder is herdsman, and his rifle is the goad used to spur the laggards forward. A convict turns out of the lane to our left and marched down the road with insouciant air and engaging gait. He is closely followed by a warder with the inseparable rifle in hand. The farming operations are by this time concluded, and soon twenty-two convicts are marshalled in couples before the gateway. The signal that all is ready is passed to the warder standing at the point aforementioned, and then, headed and followed by two armed warders, the men march down the road with short, swinging, half-military step to the prison gates not far away. As they march along they pass a group of men and women chatting gaily under the tree to their left; children are playing in the open roadway; two young ladies dressed in white with pink sashes cycle by; a drag laden with half-day trippers is pulled along by four steaming horses; the youth and maidens of the party are singing the latest music-hall ditty to the strains of an accordion. All these things are happening as the prisoners march onward in military quickstep fashion down the road and under the pentagon-shaped archway of massive stone. This is flanked by printed notices warning the reader that the assisting of a prisoner to escape is an act of felony. The convicts halt at the next gateway, through the lattice porch of which they pass slowly in couples. Them admitted through iron bars, they enter the vast outer court of the prison, where but a short moment ago we saw the guards marching to and fro on its spacious concrete pavement, Here we lose them and we turn toward the hills.

On our way we encounter an old prison warder. He tells us some of the prisoners are engaged in farming occupations and in the reclamation of the barren soil. Others are employed in the boot-shops, and a great number in dressing the stone won from the quarries. The roughest of the prisoners are allotted to the latter task. The prison farm possesses the usual compliment of horses, cattle, sheep, and fowls. The fields are hedged off in thirty-two-acre plots. Here grow cereals, root crops, &c. The farm land is being continuously extended. At the present time a batch of convicts is engaged in setting back the boundaries of the farm preparatory to the inclusion of another 800 acres. The land belonging to the prison slopes upward from the prison walls to where on the distant hillside a dark turf-line has been newly cut. “Escape?” said the old man to our query. “Yes, they are always trying to escape. But they don’t try to get away in weather such as this. It is only when the fogs are out and the mists roll up from the channel that they try to bolt. A mist will come on perhaps an hour after they have got to their place of work. Then a dash is made for liberty.” “But you fire at them,” we interject. “Yes, we fire, but we generally shoot wide so as to frighten them. A year ago a convict, in trying to escape, was shot dead. There was a lot of trouble about this. An inquest was held. No one knew how it was done. There were two warders firing at the same time, and the poor chap got killed somehow. They seldom get far away,” continued the warder. “You see, there is a five pounds reward for anyone giving information which will lead to their recovery. If we catch them we get nothing at all. I don’t think it is fair,” added the old fellow in a tone of complaint. He rambles on, in answer to our inquiries respecting the notable prisoners of Dartmoor and the general character of the men in charge. Some of them are extremely violent, and require all the natural and acquired vigilance of the warders. Not long ago one of the convicts struck his keeper with a hammer and maimed him for life. He was awarded twenty lashes with the “cat,” and the warder receives a weekly pension of forty shillings. Our informant seemed to think that justice had not been meted to either of them. He would have been greater pleased if the pension had been greater. His view of the prisoner’s sentence was summed up in the words, “He got off cheaply.” We bid him Gooday and march briskly over the moors.

The country stretches at our feet in all its barren splendour. The moorland fields slope skywards to the crests of the hills surmounted by cromlechs of stone bearing strange resemblance to ruined castles and cathedrals. Here and there the hill-sides are pierced by stone quarries. Our road leads down to the hollow, along the rocky bed of which runs a mountain stream. Below the hollows of the bridge-arches the pools of water are dimpled with sunlit breezes, and in the crannies of the rocky bed, lazy trout are lying. A cottage to the right affords a shelter from the weary road and the promise of repast. The good wife prepares it, during which operation we look around. Over the fireplace are slung a double-barrelled fowling piece and a six-chamber revolver. The head of the household follows our upward glances, and in answer to our question as to their need and use, explains that on many an occasion he has slept with them both loaded by his side. “But why?” “When the convicts are out,” is his laconic reply. Then followed an explanation of the plans usually pursued by an escaping convict, together with stories of their adventures. The first subject which possesses their minds is that of breaking into a house and of effecting a change in their outer garments. As the cottager explained to us, in such moments the convicts are desperate and capable of doing anything. The sound of a gun would frighten them away. A story told to us is interesting enough to repeat, if only for the pathos of its tragedy. A convict made a dash for freedom on a day of mist and rain. The guards fired at him, but without result. He scaled a wall, belted across the moor, and was soon swallowed up in the descending haze. He wandered for hours ever seeking an escape from the warders at his heels. He doubled again and again like a hunted hare. Night fell, and with it came temporary safety. He was perforce compelled to keep to the moors, for all the roads and mountain paths were closely watched. Morning came, but it brought little guidance. The mists hung dank and thick over everything like wetted sheets, blotting out the landmarks and all that could afford a guiding clue. For a whole day he wandered on, with heart beating at the sound of his own footstep and of every broken twig, with muscles faint from want of sleep and food, and wet to the skin with rain and gathering clouds. Suddenly the mists lifted, and in front of him the gaunt grey walls of Dartmoor prison spread themselves. For the whole two days he had wandered in a circle. He was speedily discovered and taken back again to his cell. Another convict after wandering in similar fashion was discovered fainting on the moors with bleeding feet. The strain of the attempt to escape had proved too much for him. For a whole twelve-month thereafter he was tended in hospital for nervous and physical breakdown. A Nemesis seems to pursue the convicts who try to gain their freedom. One of these managed to get as far as Plymouth, but in the streets of Devonport he was suddenly bitten by a policeman’s dog, and the terror he manifested gave the clue which led to his arrest. He was sent back to Dartmoor.

We must away, for evening is coming upon us. The fleecy clouds are blowing inward from the sea, casting black shadows across the bare hillsides. To our left a pile of stones resembles a human face surmounted by a cap, beneath the peak of which almost human eyes peer steadfastly over the moorlands. Now and again in sheltered spots we once more meet with golden gorse, purple heather, and bracken in all the glorious colours of early autumn. As we surmount the shoulder of the last hill we catch a view of a cluster of moss-covered thatched cottages in the valley around which the picturesque Devon cattle are grazing in the verdant meadows. Beyond lies Tavistock, half-hidden in the silvery mists which gild our line of sight onwards to the declining sun. A couple of cyclists rush by, oblivious of the charming features of the scene. Under the glow of the setting sun the distant hills take a tinge of golden purple and russet brown. Later on, the mists of evening are suffused with grains of gold. On the distant horizon, below which the sun is now sinking in all its glory, are fleecy clouds, lit up by its splendour until they resemble masses of fire on a ground of opaline blue. Here and there darker clouds are scattered, through the centres of which the sun burns itself with a dull red glow, reawakening memories of the lava fires seen on the slopes of Vesuvius. We enter Tavistock at a good pace, for time is pressing. We cast a hurried glance over the bridge which crosses the river Tavy, listen to the mellow music of the church bells as they toll the hour, and to the splashing of the water as it falls over the weir below. The railway station is at hand, and soon the hills reverberate to the sound of the engine as it hurries us downwards ands away.” – F. Brocklehurst – The Manchester Evening News, September 29th, 1899.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Always so interesting as I am Dartmoor born and bred .