Over the centuries numerous adventurers had set up companies to exploit Dartmoor’s natural resources, none more so than its ‘Black Gold’ – namely the huge peat deposits on the northern moor. Some of these enterprises aimed at selling dry peat, others converting it into peat charcoal, peat litter, peat parchment., and a whole host of other by-products. Amongst these various companies there was one that through mis-management, serious fraud, poor accounting and sheer negligence made a spectacular financial loss for its shareholders. Now follows its timeline from what was a brave and enthusiastic beginning to a disastrous ending.

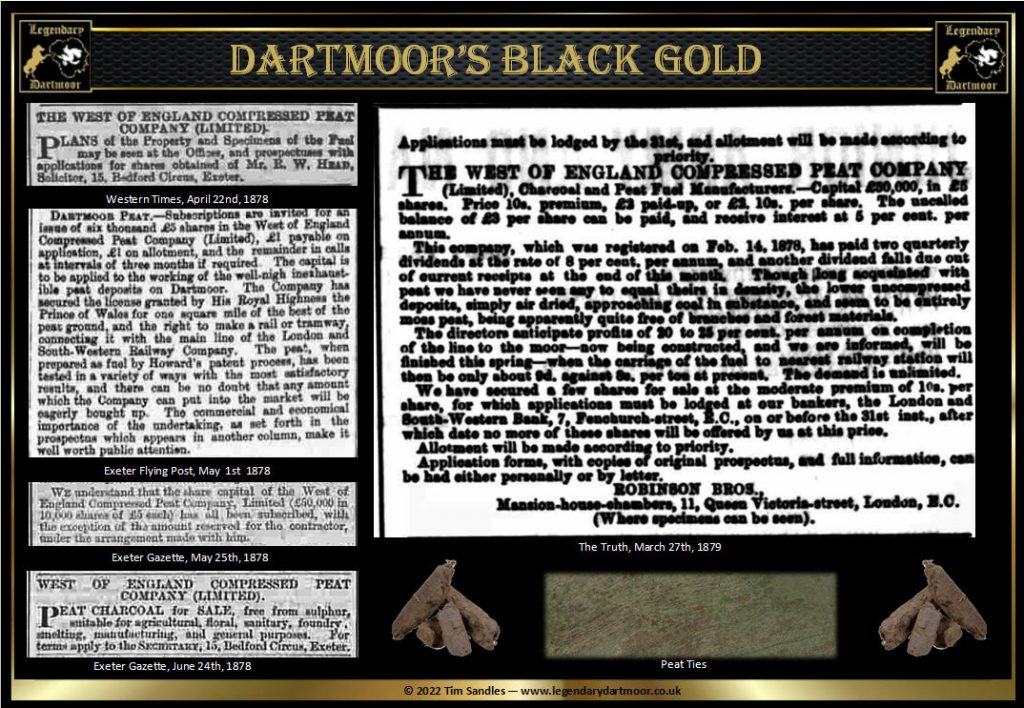

Early in 1878 the Duchy of Cornwall granted a licence to The West of England Compressed Peat Company Ltd to enable the extraction of peat on 1 square mile of their lands. The annual cost of the licence was £100 along with one-twentieth dues. Additionally, permission was granted for the right to construct a tramway to the peat lands.

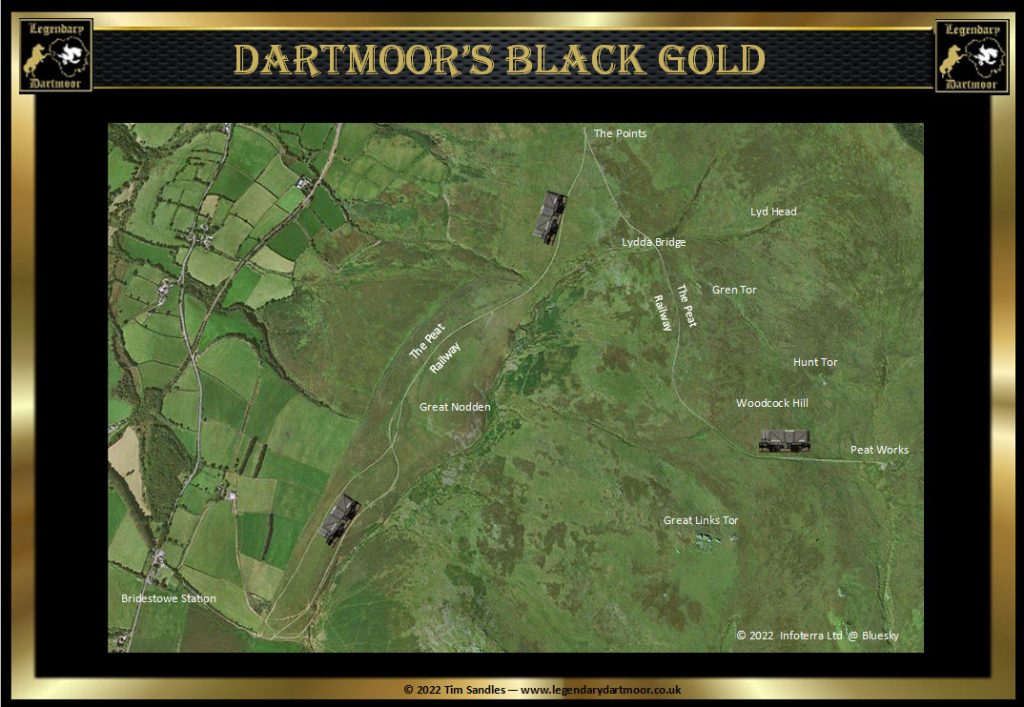

On the 18th of April 1878 many of the local papers announced that the prospectus for the West of England Compressed Peat Company Limited had been announced. The capital of the company was stated as being £50,000 comprising of 1,000 £5 shares. The purpose of the company was to work the huge peat deposits extending from Amicombe Hill to Woodcock Hill in the north to Tavy Cleave on the south and the Rattlebrook on the west whilst going near the West Okement river and the northeast and running parallel with it. It was proposed to build a railway which connected the peat beds to the Bridstowe railway station which would provide an economic route to the markets. The benefit of this scheme was not only to return a profit but to provide peat at half the cost of coal. This also meant that peat was far more superior to coal in the manufacture of gas plus it was free from sulphurous fumes. As a smelting fuel it was far superior to coal and once again no sulphurous fumes. Additionally, for agricultural use it proved to be a highly effect fertiliser as it had the ability to taking up to eighty percent of its weight in moisture and instantly corrects and decomposes all putrescent matter. The whole concept of the business was to convert the peat by a process of hydraulic compression which was the patented brain-child of one John Howard from Exeter. His patented process was as follows – “The peat is cut from the bed and thrown into an igneous apparatus, from which it almost immediately passes out pressed and prepared. It is then placed in a drying frame, whence it quickly issues ready to be stacked or stored for use as a fuel.” Also involved in the venture was Fredrick Thomas who it was said had personally obtained the license to extract peat from the Duchy of Cornwall.

In the May of 1878, the West of England Compressed Company Ltd invited reporters from the local press to a guided tour of the intended works.

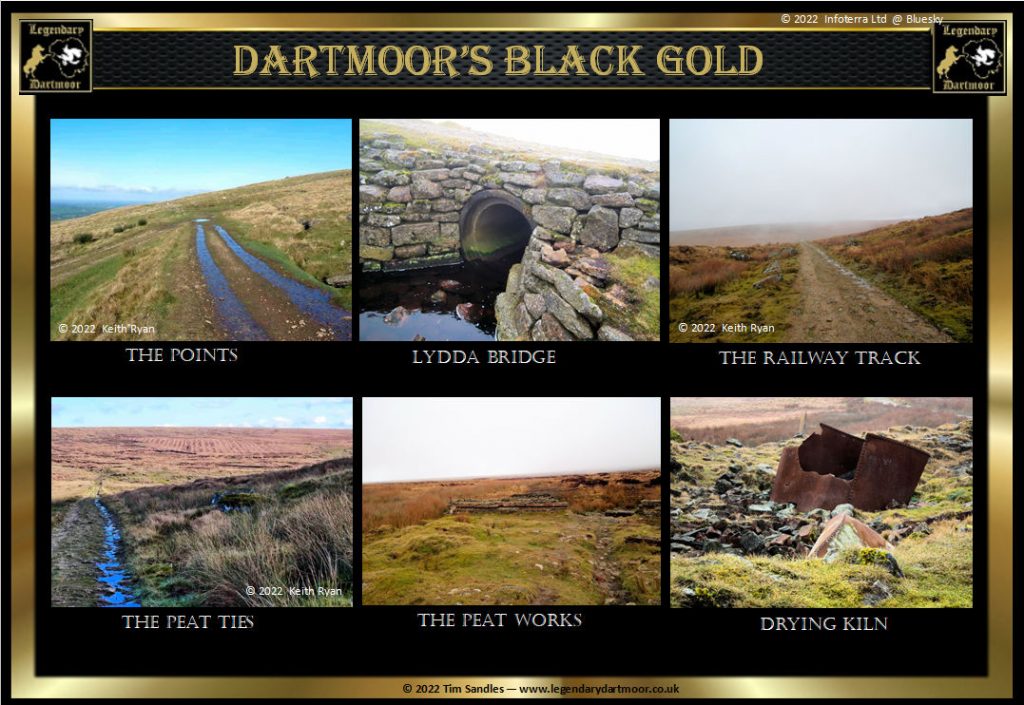

“In little more than an hour after leaving Exeter the train arrived at the Bridestowe Station of the London and South Western Railway, and a few minutes’ walk brought us to the foot of Dartmoor. From this point the engineer of the Company pointed out the route of the tramway which it is intended to construct (about 3½ miles) for the conveyance of the material from the peat grounds to Bridestowe Station, as we strolled up the Moor the practicality of the proposed rail became more apparent, nature having facilitated the undertaking by providing a gentle incline which winds round the “Great Nodden Hill” from its base to the highest point required for carrying the line to the peat ground, so that the construction of this railway up a Dartmoor tor, instead of presenting any difficulties whatever, will be very simple and economical, for beyond one small culvert no bridges or embankments will be required other than that which nature has provided.

Whilst anticipating to see very large quantities of peat we must confess the company were hardly prepared to see what has been termed such “inexhaustible resources” for on either side almost as far as the eye could scan there was visible one vast bed of rich black peat, so dense that it was with some difficulty it could be probed, and which appeared to increase in depth from six or eight to twenty or thirty feet and we were informed that there are many hundreds of acres even deeper than this, but wether it be so or not, no one can visit the deposits without being impressed with the fact that the quantities are unlimited…

The Company estimate that there are over five millions of tons of peat within the limits. It was stated that large contracts had been made for the sale of the article at 12s. per ton, and after allowing every possible deduction the Company calculate this would give a net profit of 4s. per ton. Assuming, however, that instead of five million there are only four million tons capable of being rendered marketable, this at a net profit of 4s. per ton would be equal to £800,00 on the four million tons…

As soon as the Tramway is complete there will probably be a ready sale for the fuel, and a demand by the Railway Companies for use by their locomotives. Taking into consideration the little expense in working and the absence of all danger in obtaining the commodity, the value of the Company’s undertaking is proportionally increased. There is no doubt that the Tramway will be the key to success in this undertaking. Should it be made, the energy devoted to turning those great natural resources to account will be further rewarded since the line will pass through some of the finest granite and iron stone on the Moor. Under the peat lie vast quantities of china clay.” – The Western Times, May 6th, 1878.

Having had the above endorsement published the Company wasted no time in advertising for share subscriptions and by the 25th of May it was announced that the required share subscription had been reached. By the June of 1878 numerous adverts were appearing offering peat sale. On Monday the 23rd of September 1878 amidst great pomp and ceremony the first sod of earth for the intended railway was cut. At the point where the peat railway would join the main line the High Sherriff of Devon officially cut the first sod of earth. He took a silver spade, cut the sod, and placed it in a mahogany wheelbarrow which was then trundled along a temporary platform and tipped it into a nearby field. Lunch was then served in a marquee for all the attendees which numbered over 50. It was also announced during the many speeches and toasts that the Government had already placed orders to supply the Woolwich Arsenal. This came about thanks to one Captain Peacock R.N. who thought that by burning peat instead of coal in their steam ships would be a much cheaper proposition. The estimated cost of building the railway was said at the time to be around £6,000.

By the end of September, the first share dividend was decaled a return of 8% and it was suggested that once the railway line had been completed this would rise. By the December 1878 local adverts were appearing targeted at the “unemployed of Exeter” offering work at three shillings a day. Following this announcement, a number of unemployed men attended the magistrates court to ask the mayor to open a subscription to “alleviate their distress.” The spokesman for the delegation informed the Court that they were aware of the vacancies at the peat works but were concerned that there were not enough lodgings for the men and the men would not sleep out on the Moor. At the end of December 1878, the second share dividend was declared and despite the optimism of September it still remained at 8%. At the Annual General Meeting of the West of England Compressed Peat Company Limited in the February of 1879 it was announced that all the shareholders who attended accounted for £4,520 shares forming £13,136 of the capital. In the march of the same year another notice appeared stating that the Company had paid 8% dividends and on completion of the railroad they anticipate a return of between 30 and 35% dividends. It also said that they have “secured a few shares” and were offering them at a one-off bargain price of 10s. a share. Unfortunately, in the April of 1879 the third quarterly dividend was announced at the same old 8%. An auction at the Queen’s Hotel in Exeter was held on the 27th of May 1879 at which 162 fully paid-up shares in the W.E.C.P.C. Ltd. (sorry I am fed up of writing the Company’s full name) were offered at a starting price of £2 a share – only 25 were sold at £2.

Good news came early in the February of 1880 when the announcement was made that the line which the W.E.C.P.C. Ltd. were making “only require some finishing operations in order to render them ready of opening.” At the same time the third Annual Meeting of the Company was held and the report was seemingly full of joy and expectation. John Howard proudly stated that “The construction of the Company’s Railway was completed, with the exception of 143 yards in length, situate between 342 and 348½ chains to join the embankment between 364 and 372, and a portion of the top ballast. Two thirds of the fencing had been fixed, and the wire was on the ground for fixing of the remainder. Out of the 4 miles and 56 chains of bottom ballast required to be done 4 miles and 22 chains had been executed, thus leaving only 34 chains to be completed. The permanent way had been laid complete for a distance of between two and three miles, starting from the Bridestowe end, and over which the locomotion engine and trucks pass daily. The completion of the last bridge, which was delayed by the frost, was now being proceeded with, and would no doubt be finished in about 14 days. The whole of the culverts which had been required were completed.” Howard also pointed out that instead of the originally intended 2ft. 6” tramway a 4 feet 8½ inch gauge railway had been laid which was identical to that used by the London and South West Railway. In effect this meant the peat could be taken to Bridestowe in ordinary railway trucks instead of tram trucks thus saving time and money.

The chairman then announced that it was obvious that those companies that were relying solely on peat production were struggling. But those that had made the production of peat charcoal their priority were now thriving. It appears that good old John Howard had already taken out a patent for the process and found a suitable site to do it. The excitement was all based on the fact that huge quantities of peat charcoal were being used in agricultural fertilisers and thus supplying the market at huge profits. That being the whole idea it was sold on the pretence of assisting the depressed agricultural industry in their time of need. Supposedly a large fertiliser manufacturer with works in Gloucestershire would be looking for between 300 and 400 tons of peat charcoal a week. If the Company supplied 100 ton a week it would mean another £7,500 a year profit on their calculations., 200 tons week would double this figure. The proposal was agreed and work on a peat charcoal works got the green light. – The Western Times, February 3rd, 1880.

In the May of 1880, an extraordinary meeting of all the members of the W.E.C.P.C. Ltd. was called where it was seeking authorisation to issue another 516 shares at £5 each along with 800 preference shares also at £5. At another meeting in June the chairman declared that the Company had a deficit of £6,000 due to the fact that they had paid £3,000 more than the estimate for building the railway and that they were sitting on 516 unsold shares. To overcome this problem and raise money for the peat charcoal initiative it would be necessary to go ahead with the sale of additional shares – the motion was carried. The intention then was to build sixteen drying kilns at the works. At the time the estimated production costs for a ton of peat charcoal was 18s. a ton with the market price coming in at £2 10s. a ton. With the sixteen kilns producing about 70 tons of peat charcoal a week this would return around £5,000 profit a year. Shortly after this meeting and advert appeared wishing to hire a five to seven horsepower portable engine form the 14th of June to the 1st of September. If a driver came with the engine they would pay them 24s. a week.

By the August of 1880 there were twelve drying kilns and grinding machines at the Rattlebrook Head works. Another focused advertising campaign was launched in the September of 1880 aimed at manure merchants, agriculturalists, and iron founders with the offer of free samples of the peat charcoal. In a Company Meeting in the February of 1881 it was announced that the railway was completed, twelve drying ovens, a stationary engine and boiler along with a disintegrating machine for grinding had been installed at the Rattlebrook Works. The works had 3,800 tons of peat cut and stacked awaiting the conversion into charcoal. It was also announced that the Duchy of Cornwall had agreed an extension on their lease for the Rattlebrook Sett and the railway for another 31 years. Somewhat surprisingly it was also mentioned that to save money the empty trucks were taken back to the works by horsepower (they travelled down by the force of gravity) to save money – alarm bells or what?

A startling newspaper announcement was made that the next shareholders report for the W.E.C.P.C. Ltd was due on the following day – 15th of March 1881 and the dire truth of matter was revealed. The hot topic concerned Fredrick Thomas and John Howard. It was alleged that when the Company was set up Thomas had sold his Duchy licence to them for £8,000 in shares. Along with this John Howard had sold his patent for the hydraulic compression process to the W.E.C.P.C for 100 paid-up company shares valued at £8,335. However, despite all previous claims no machinery or a model machine was ever seen. An engineer, Mr. Wilson of Exeter was then hired to produce a drying machine according to Howard’s design. Having done so a trial of the machine was ordered at the cost of £56. Howard was asked to attend the test trial but never turned up on the day, but it still went ahead. It soon became clear to the directors that the patented machine was worthless and not fit for purpose. It was then decided not to pay the Patent Office the outstanding debt which meant they had forfeited the patent. Thomas and Howard had jointly sold the Company the leases they owned for the Walkham Head peat lands for £10,000 in shares but the annual cost to them was a mere £89. By some means both Howard and Thomas had managed to sell all of their shares which meant the W.E.C.P.C. Ltd had wasted just over £26,000. As if all that was not bad enough a sum of £50,000 had been paid by the directors in salaries.

On the 15th of March 1881 the Annual General Meeting of the W.E.C.P.C. was held in London. As expected, the above underhand dealings of Howard and Thomas officially came to light much to the shareholders amazement. As predicted all of Thomas’s and Howard’s underhand dealings were made public knowledge. It was also brought to attention that Howard had been appointed as the engineer to build a 2ft. 6in. tramway in 1878 at an estimated cost of £6,591. A tender for the work was accepted from one Mr. Brotheridge to build the tramway for £6,944. It was agreed that the Directors of W.E.C.P.C. reserved the right to exchange the contract to a 4ft. 8½in. gauge railway at a cost of £10,802. That right was duly exercised with the stipulation the railway had to be completed by the 1st of August 1879 or penalties would be incurred. By the Spring of 1880 Brotheridge had not completed the work but for some reason the penalties for not completing the work were never charged. In the end the total costs of building the railway amounted to £15,000. This clearly was the reason to use horsepower to draw the trucks – to recoup some of the extra money spent on the railway. The report also noted that the London and South West Railway Company had since refused to allow the waggons to pass over their line due to the steepness of the gradient. Despite all this dire news the Committee tried to reassure the shareholders that the operation was still viable. The report concluded by saying – “If the shareholders desire to make another effort to carry out the original purposes for which the Company was floated, its management must be placed in the hands of a new Board of Directors. With regard to the future prospects of the Company, your committee still hope that something may be done by care, energy, and economy, supported by the united efforts of the whole body of shareholders, to build up a business out of the ruins of the past.” The report was accepted by the meeting and a new board of four Directors was elected. – The Exeter Flying Post, March 16th, 1881.

The fifth ordinary meeting of the Company was held on the 7th February 1882. It was what was described as a “stormy and excited character,” and lasted for over three hours. After much heated debate a resolution was put forward to voluntarily wind up the company which was accepted. It was the proposed that the directors be authorised to put the property on the market before appointing a liquidator. This was not agreed to and the Chairman, Rev. John Fletcher was appointed as liquidator. – The Western Times, February 7TH, 1882. By all appearances both Howard and Thomas had conspired to defraud the Company of huge sums of money from the very beginning and although it was surmised no case of fraud was ever proven.

On the 7th of April 1882 another shareholder’s meeting was held where it formally adopted the resolution to wind the company up. By the January of 1883 the Duchy of Cornwall were sent a formal application to liquidate the W.E.C.P.C. Ltd. The duchy also received a request to grant a new licence for peat extraction to Messrs. Campbell, Dews and Cox, this was granted in the December of that year. The new company was called “Cox’s Patent Prepared Peat Litter Company Ltd.” This Company had paid £12,832 for the West of England Compress Peat Company Ltd. This purchase included the railway, the rolling stock, plant, machinery, ovens, and buildings. By means of Cox’s patent machinery it was the intent to produce peat moss litter for use in stables and other agricultural buildings. This litter was claimed to quickly absorb urine and fix ammonia and be a healthier option. It was also claimed to be more economic alternative to straw. The peat charcoal production was also to be continued under the new company.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor