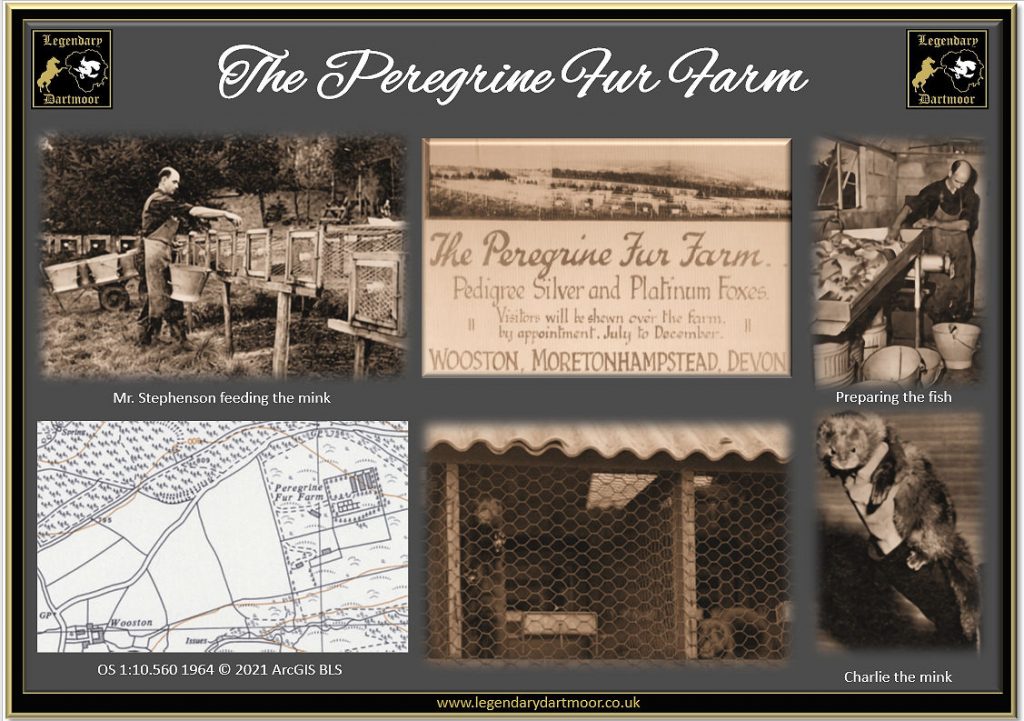

If you look on a modern Ordnance Survey map at grid reference SX 7708 8925 you will see the enigmatic and singular name of “Peregrine”. Was this once or still is the haunt of the Peregrine falcon? Now look at the Ordnance Survey map from 1964 below and the mystery will be solved. It is the onetime location of a fur farm known as the “Peregrine Fur Farm” which was owned by Mr. J. H. F. Stevenson. This enterprise was first established in 1938 breeding primarily foxes for their pelts. As the years progressed the fashion industry began to turn away from using silver fox pelts to those of mink. In 1951 the first mink arrived at the Peregrine Fur Farm and by 1955 their numbers had grown to over 400 animals. Reportedly at its peak it was estimated that the farm processed over 4,000 mink and employed four full-time workers with more temporary staff when the pelts were processed. As can be seen below, farming mink was no easy task, it was labour intensive and at times difficult to source enough economically viable food sources.

“Mr. J.H F. Stevenson has his farm on the borders of Dartmoor, near Moretonhampstead. With 400 animals to feed, he has to make up 3 cwt. Of feed a day, of which 68 percent is fish. He visits eight shops in Exeter five days a week to collect 2½ – 3cwt of fish waste each day. From the slaughterhouse he collects liver, and essential part of the mink feed, cattle trips and sheep’s’ paunches as wanted. The fish waste costs Mr. Stephenson 5s. per week per shop. Liver is 5d. per lb, and he used 10 percent in the feed. Sheep’s paunches and tripe cost 5s. per cwt., and by salvaging the fat on the liver and the tripe, Mr. Stephenson can collect a “rebate” from the fat melters at the rate of 10s. per cwt.

With no electricity laid on his premises, Mr. Stephenson’s only form of cold store is a small Nissen-type shelter dug into the hillside. For most part of the year he can get adequate supplies and feed fresh food each day, but in the summer, when the new stock must be adequately fed to ensure good-size pelts in the winter and when the mothers must receive their full ration, the supply of fish waste available is insufficient on occasions and emergency steps have to be taken to find sufficient food. Given proper cold storage, Mr. Stevenson’s problem would be solved, for a “buffer” supply of fish could be kept – an insurance against possible deuteriation of valuable stock. As it is, when such occasions arise, generally towards the week-end, it means a call to neighbouring breeders in the hope that they can help out, or a telegram to a port fish merchant to rail some fish waste, or, at the worst, a cut in rations for the breeding stock to ensure the youngsters get sufficient. On the face of it the larger mink farms pay dearly for their cheap feeding. Dearly because the collection of it entails considerable mileage by private transport, and a deal of time on the part of the proprietor of the farm, or his assistants. Both these factors are rarely accounted for when considering the cost of feeding mink in the British Isles – and never reckoned with by the newcomer to the industry.” – Illustrated Sporting News, January 5th, 1955. When Mr. Stevenson remarked about his neighbouring breeders he was probably referring to nearby, the ‘Wild Pine Fur Ranchers‘ at Teigncombe, and the Hillcrest Farm at Teignmouth.

The local climate and location of the farm was ideal as it was remote, sheltered and far away from other habitations, I would imagine that on hot days the smell of the fish and offal could be ‘ripe’ to say the least. However, as can be seen from the advert below Mr. Stevenson was allowing visitors to his farm on certain days throughout the summer, don’t think it would attract many people today though? By the 1960s there was a change in the fashion industry with cheaper and more humane substitutes for natural fur were being favoured. The outcome of this change was that in 1969 the Peregrine Fur Farm closed down

Mr. Stevenson’s timely tips on mink farming – “A fur farmer, no matter what animal he breeds, faces all the usual risks of livestock keeping in the way of disease, difficulties over food supplies and so on; but, over-riding them all, holding his fate in her delicate hands, is My Lady Fashion.”

“A guard fence surrounding the pens has a dual purpose. To prevent an escaped mink getting right away and to keep dogs and other unauthorised visitors away from the stock. While the loss of an escaped mink is bad enough, it is frequently followed by heavy claims for damages from enraged poultry keepers whose birds have been killed by ‘a black shiny animal like a ferret.” By 1965 there was a growing population of mink around the Exe, Dart and Teign rivers all of which were said to have escaped from commercial farms in the county. In that year there were three trappers employed to catch them in Devonshire and over 180 were caught. As the Peregrine Farm was less than a kilometre away from the river Teign it is quite possible that some mink escaped from there and established themselves around the river.

“From September-October tail-biting is another worry that afflicts breeders at this time of the year. Where this is merely biting at the fur, often at the tip, and shearing it, in many cases it is simply boredom, and a small block of wood or a large pine cone to play with is all that is needed to break the habit. Biting at the flesh of the tail, either at the tip or down its length is said to be due to irritation caused by damage to the actual tail structure by rough handling the prevention is obvious, but the cure is amputation, or pelting.”

“There are several methods of killing; electrocution in specially made cages, usually several in a “battery”; carbon monoxide gas from the exhaust of a car; cyanide; injections of Epsom salts to the heart. An increasing number of breeders are learning the knack of breaking necks, although many find that this is only practicable with females. I use chloroform.”

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

My Dad, as a vet based in Moretonhampstead, used to treat John Stevenson’s mink on Peregrine Fur Farm when called. My school friend Anne was his younger daughter (Jane was older than us…) so I went there occasionally but was terrified of the mink, reputed to be vicious. We left the area when I was 11 and I lost touch with my friend Anne. Never understood why people who eat meat and wear leather opose fur farming.

As a vegetarian who uses neither leather nor eats meat, I can understand your point of view. However, there is a real difference between using eg, cow skin, which is a by product of the meat industry, where the domesticated cows are allowed to feed on grass in open fields for at least their lifetime, and keeping wild (or domesticated) animals imprisoned in conditions which are so stressful that it often drives them mad, causing them to self harm. This is evident even in the above piece. And for this to be inflicted on other living creatures just for the sake of fashion, sport or simply to make money, is, in my view particularly immoral & unacceptable. Perhaps you should have been taught to see it from the minks point of view. Perhaps they thought it humans who were the vicious ones.